The Critical Value of Digital Remix Practices in the Arts for Producing Culture and Innovation

By: Max Jala

The term ‘remix’ derives from the model of music production (cut/copy and paste) quasi-intrinsic to Jamaican dance hall/dub music of the late 1960s. (Veal, 2007) Nowadays, remixing (the act of taking samples from pre-existing materials to combine or contort them in novel ways) is ubiquitous in art, music, and culture at large. This past decade has seen the emergence of Web 2.0 applications that have led to the rampant proliferation of remixing as a communicative tool, most significantly at a grassroots, vernacular level: (think ‘memes’). The importance and visibility of remixing in today’s society has led scholars to coin the term ‘remix culture’, which has become an increasingly popular area of research.

“Human culture is always derivative . . . New art builds on old art”.

- Daphne Keller (2008)

Remix culture, however, is by no means a 21st Century phenomenon. Remixing is and has always been the very means by which innovation and cultural progress occur. They do not manifest in a void, but rather through iterative progress and recombination of existing building blocks. (Salter & Alexy, 2014; Schumpeter, 1942) This stands in opposition to the traditional understanding that innovation is purely born from a spontaneous, epiphanic "Aha! Moment" (Birkinshaw et al., 2012) most famously encapsulated in the image of an apple falling on Isaac Newton's head. The same sense of lineage applies to culture. One only needs to consider the bifurcated genealogy of music genres to observe the sustained and diverse influence one culture has on adjacent and future cultures. This paper will look to investigate the critical value of remix practices in digital arts in terms of producing culture and driving innovation, with special emphasis on the methods in which it can do so. The two aspects of culture/innovation production that will be examined are:

- Remixing as an act of curation and meaningful preservation

- Remixing as a strategy for disruption, change, and innovation

Remixing as an Act of Curation and Meaningful Preservation

The act of preserving culture has been essential to producing culture and knowledge through the ages. It serves as a means to go forwards through the learnings and lessons to be had from what came before. But simple preservation is not nearly enough. In the words of Mark Fisher (2009), “A culture that is merely preserved is no culture at all.”

“All mankind is of one author, and is one volume; when one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated”

- John Donne (1923)

Only by actively engaging, contesting, and building on culture of old do we do it proper service, allowing it to live today with relevance and real meaning.

The most obvious and literal way in which cultural heritage can die is in the physical sense - even with immense care from museums and heritage groups such as UNESCO, works of art and heritage sites are prone to inevitable degradation and eventual dissolution. But while there is real value in this work to preserve relics in their original form, keeping them from death, I contend that art and heritage groups should instead prioritise life by looking to the digital realm, preserving cultural objects in digital forms that can be remixed and manipulated made anew by present and future generations. In his Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Mark Fisher makes a similar point: he loathed the role of galleries and museums in converting “practices, rituals and beliefs” of the past into objects of vanity - “ironised, transformed into artifacts.” These sentiments inform the notion of meaningful preservation. It is a form of cultural preservation more akin to fermentation in which culture is preserved alive and actively contaminated, rather than doomed to a state of taxidermy.

An example of this process done right is ReACH (Reproductions of Art and Cultural Heritage). ReACH has, in the last few years, brought together the global museum and heritage community to explore how our imperiled cultural heritage can be preserved in our digital era of 3D printing, ultra-high-resolution scanning, and drone technology, and to debate the creative opportunities that copying these works offers a global audience. (Cormier, 2018)

Looking further afield, beyond the of major museums and gallery spaces, there also exists the imperative potential to curate and remix lesser-known works or ideas from the “depositories of unwanted capitalist surplus”. (Church, 2021) Indeed, in a world of universals (subject vs object, right vs wrong), it is increasingly important for art to strive towards presenting alternative ideologies and tastes to what is most commonly prescribed. An example of this can be seen in the music world, where artists have for years engaged in crate-digging - scouring record shops and flea markets for old recordings to be repurposed and revived (remixing in the most literal sense) to present sounds that can challenge and deviate from pop culture. In the context of wider digital arts, this practice allows for artists to act as curators of culture. They salvage ideas and culture that were deemed unimportant or unproductive in the dualistic framing of value, remix them to grant them relevance and salience, and in so doing actively create potential in the form of new futures.

Another consideration is that digital waste has started to become a massive ecological problem, with insatiable consumer appetites driving technology into a cannibalistic cycle of redundancy. The end result has led to landfills piling up with masses of electronic junk - in 2019 alone, 53.6 million tonnes of E-waste was produced and only 17% was recycled sustainably. (Graham 2020) One huge benefit a remix approach has is its ability to take digital waste and repurpose it to serve as art. Digital art installations have the potential to alleviate some of the burden by granting obsolete objects a second life. This can also serve to meaningfully preserve some of our technological heritage in a cultural situation in which the capitalist agenda would rather see such ‘unproductive’ material cease to exist. I would argue this is something that extends beyond the frame of the critical, into the imperative practical.

Remixing as a Strategy for Communication, Disruption, and Innovation

Art has a unique ability to inspire new thoughts, ideas, or beliefs - in short, to create fantasy - even if this fantasy comes about through the unconventional means of disturbance or provocation. Society has historically granted art the unique position to present ideas that are uncomfortable, anxiety-provoking or ‘politically incorrect’. And though this affordance may be reflective of the trivialisation of art within capitalist constructs (“it’s just art” mentality), the need to present radical ideas, new or just simply different, is something art still needs to strive to do. It is vital to a functional political and societal landscape to have such discourse, with proper contention of ideas.

In Capitalist Realism, Mark Fisher (2009) states it would be “easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”. While this statement and his general conclusions from the piece seem bleak, his wider writings on the concept of hauntology (a term first introduced by Jacques Derrida (1994) in Spectres of Marx) reference the return or persistence of elements from the past, as in the manner of a ghost. Fisher alludes to a need for art to strive to be critical - it must acknowledge and communicate the critical state of the world and the critical need for change and new futures. Hauntology is now a loose genre of music that evokes a sense of yearning and “nostalgia for a future that never came to pass” (Whiteley S & Rambarran S, 2016). It is fixated on the idea of “decaying memory and lost futures” (Pitchfork, 2017) Remixing in wider digital arts has the opportunity to communicate and reinvigorate these ‘lost futures’ to challenge the status quo of capitalism and dualistic modes of thinking - sparking cultural change and innovation.

Cesar & Lois are an example of a contemporary art collective applying remix techniques in digital arts to generate new modes of thought. They state an intent to “imagine new configurations for what we understand (social, economic, technological) networks and intelligences”. (Solomon and Baio, 2020) Their works are rooted in developing “ecosystemic” forms of artificial intelligence (AI) that integrate and remix different logic systems in a multi-species (pre-human and human) collaboration. These AI’s are networked and decentralised as opposed to the norm of individual anthropocentric forms of intelligences. Through this remixed network approach, they hope such AI can propose global and inclusive solutions to the grave ecological threats currently facing the planet such as climate change and global pandemics - these --solutions that will not only account for the needs of humans but also equally consider the requirements of an expanded community including “all planetary constituents”.

In their Degenerative Cultures, Cesar & Lois developed such an AI based on the Physarum polycephalum (slime-mold) to directly remix the book The Dream of Descartes by Jacques Maritain (1944). In a form of poetic erasure, the bacterial AI was made to eat away at the text, removing words, to transform and subvert its dualist, anthropocentric underpinnings. This project demonstrates the potential artistic poignancy and communicative potency of remix practices in digital arts. Their wider ambitions for remixed multi-species AI imagine innovative solutions for “societal inequities, climate crises and global pandemics” go beyond the needs of humans to that of the global community (human, non-human, and environment). In doing so, their artwork challenges the “current human sociotechnical structures” that are “based in the epistemology of modernity”, and notions of human exceptionalism that only serve “a selection of human societies”. (Solomon and Baio, 2020)

However, the potential of remixing for communicative innovation and disruption is not merely limited to the few with access to cutting-edge technological tools such as AI. In fact, quite the opposite is true -- at the time of writing, new media technologies and Web 2.0 applications designed for communication and creativity have seen an “explosion of vernacular creativity in the form of memes, Youtube videos, remixes and mashups, fan fiction, and many other creative genres and user-generated content”. (Literat, 2019) This vernacular form of creativity, which forms the basis of today’s digital remix culture, is the definitive medium of communication of our present time. Its impact on political participation among the grassroots has been immense with it “enabling people to express how they feel about politics and society in a way that was not possible before the internet”. While the harmful effects of this digital remix phenomenon are undeniable, it has led the layman to be “active constructors of meaning, rather than passive digesters of prescribed history and content”. (Gainer & Lapp, 2010) Digital remix culture has empowered virtually everyone to create dialogue in and influence the political sphere - for better or for worse.

Conclusion

The prominence, visibility and impact of remixing at work in culture is at its peak in this digital era. The effect of digital remix culture has massively democratised social and political commentary and creativity for the masses, but with it, has at the same time also engorged us with an overabundance of information and opinion, incubating spaces where information may exist without meaning or context, and unhealthy opinions and ideals are can take on a twisted life (and truth) of their own.

Despite the seemingly sprawling and virile nature of digital remix culture, it also comes with a cannibalistic sense of stagnation in which pop culture is constantly feeding off itself, propagating the same old colonialistic ideals of value and taste. Culture has become transfixed on the popular, the ‘viral’, the established, addicted to pastiche and nostalgia (as Mark Fisher puts it), no longer able to experiment with novel forms and propose futures substantially different from the present. Though remix culture has certainly proliferated this issue, it too has the ability to confront it.

“[I]t matters what ideas we use to think other ideas (with)”.

- Donna Haraway (2016)

With these issues of information overabundance and cultural stagnation in mind, it is crucial, now more than ever, that artists continue to act as curators, rummaging and filtering through culture to renew and re-present “relics of the future in the unactivated potentials of the past”. (Fisher, 2009) Beyond this, artists need to utilise remix tactics that have become ubiquitous to our culture, to bring about disruption and change. If indeed the “slow cancellation of the future” (Berardi, 2011) is already upon us, and we are beyond surmounting existing capitalist and dualist constructs, then I would like to propose that the critical value of digital remix practices in art is its ability to reinvigorate past futures, to create peripheral worlds and communities where marginalised ideas and beliefs can exist.

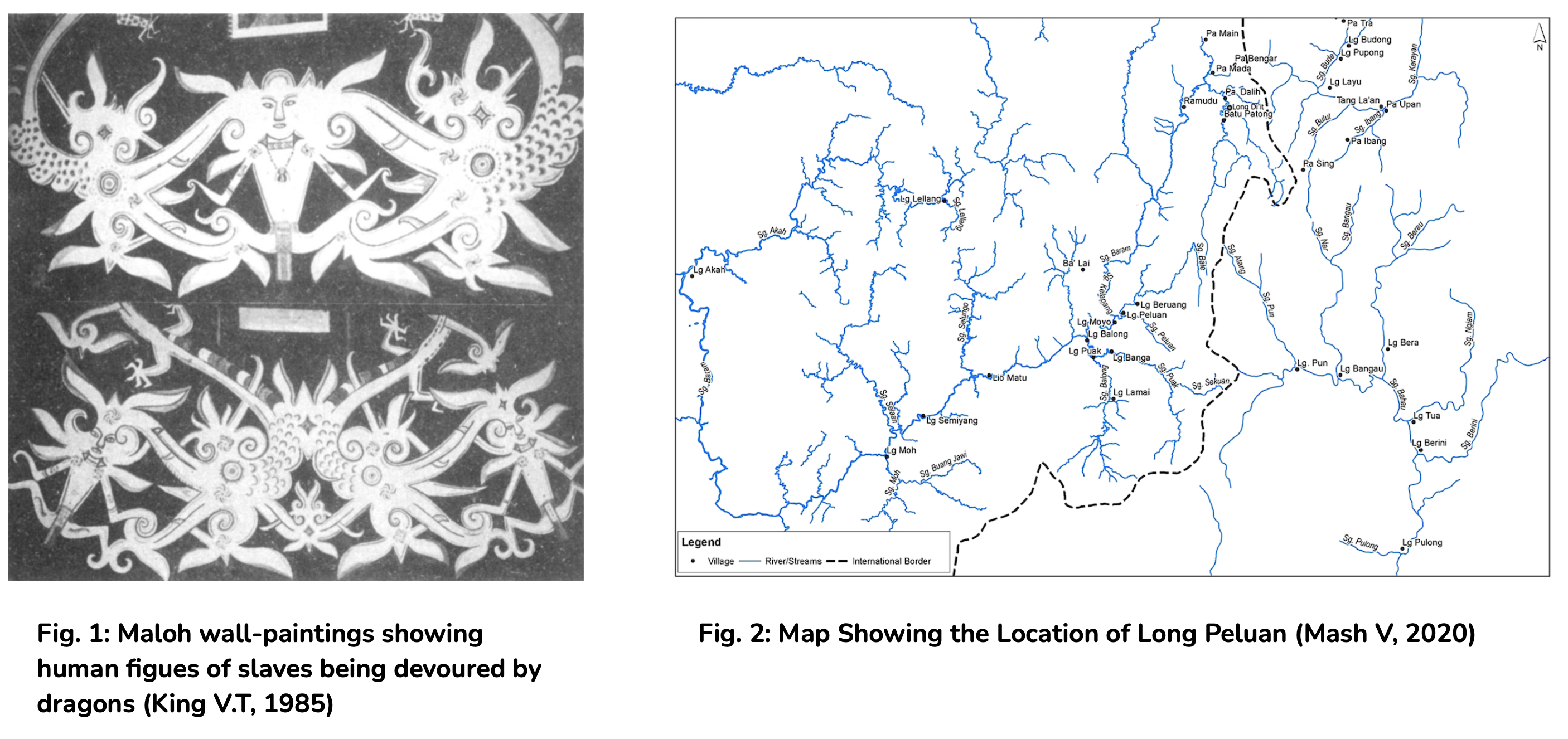

Artefact: Remixing Kelabit Sound and Imagery

The Kelabit people are the smallest indigenous group in the state of Sarawak with a population of approximately 5200 (in 2000). Their main settlement is Bario which is a community of 13 to 16 villages in the Kelabit Highlands of Sarawak, Malaysia. As with most indigenous groups its customs and traditions are fading as cultural consolidation occurs with many migrating to urban areas (as my father and family all did) - it is estimated that only 1200 still live in their remote homeland of Bario.

With this in mind, I wanted to remix Kelabit art as a means of cultural preservation, in an attempt to renew and reinvigorate dying art forms with my own personal taste and intuition.

My artefact is an audiovisual piece made completely of found materials from the Internet. The sounds of this piece are sampled from an old recording of sape performance (traditional instrument of the Dayak people) and another recording of a choral recital entitled ‘Tutu udan nepara’ which translates to hailstorm.

[unex_embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ep5MaeiTcZA&t=215s&ab_channel=AmeiJaya[/embed]

[unex_embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vKXvzn9mrsA&ab_channel=VariousArtists-Topic[/embed]

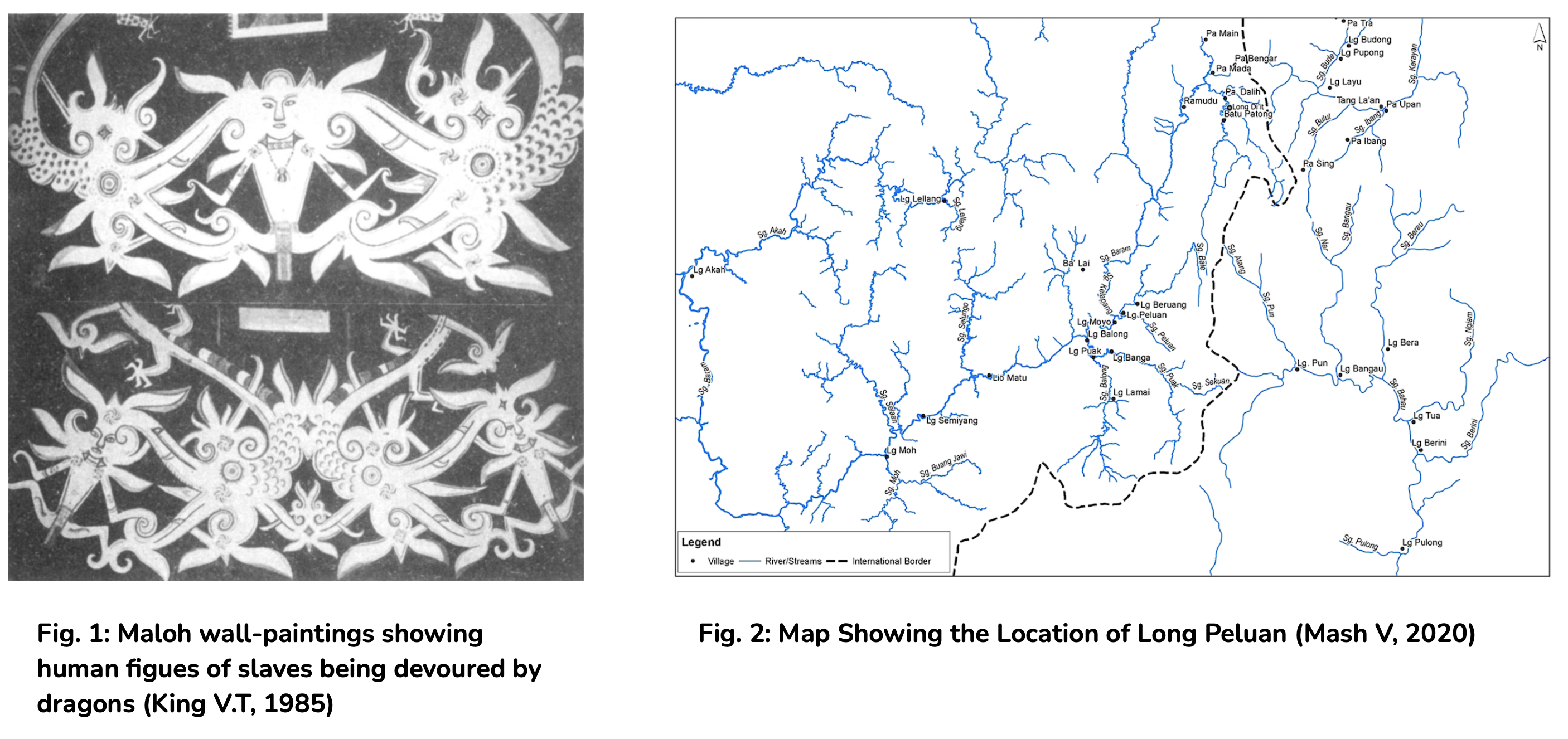

The visuals are composed of old images retrieved from journals published online:

The resulting artwork is a contemporary audiovisual piece imagining a new future for these lost artifacts. Both sound and visual samples are distorted and morphed significantly - reflecting the argument that cultural objects need to be contested, contaminated and actively engaged in to have real life today.

[unex_embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD80k1yCubM&ab_channel=MaxJala[/embed]

Bibliography

Berardi, F, Genosko, G. and Thoburn, N. (2011) After the Future. (eds). London: AK Press.

Birkinshaw, J., Bouquet, C. and Barsoux, J.-L. (2012). “The 5 Myths of Innovation”, MIT Sloan Management Review 52(2): 43–50.

CORMIER, B. (2018). Copy culture: sharing in the age of digital reproduction.

Church, S. (2021). Funes the Crate Digger: AI, Perception, and Recall.

Derrida, J. (1994). “Spectres of Marx”. New Left Review. 205, 31-58.

Donne, J (1624). Devotions upon Emergent Occasions.

Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative?.

Gainer, Jesse S., and Lapp, D. (2010). “Remixing Old and New Literacies = Motivated Students.”

The English Journal 100, no. 1 : 58–64. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20787692

Graham, E. (2020). 10 Shocking facts from The Global E-waste Monitor - S2S News. [online]

[Accessed 30 July 2021].

Haraway, D (2016), Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene

Keller, D. (2008). “The Musician as Thief: Digital Culture and Copyright Law.” In P.D. Miller (Ed.), Sound Unbound: Sampling Digital Music and Culture (pp.135-150). Cambridge: MIT Press.

King, V. (1985). “Symbols of Social Differentiation: A Comparative Investigation of Signs, the Signified and Symbolic Meanings in Borneo”. Anthropos, 80(1/3), 125-152. Retrieved July 30, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40460884

Literat, I. (2019). “Make, share, review, remix: Unpacking the impact of the internet on contemporary creativity”. Convergence, 25(5–6), 1168–1184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517751391

Maritain, J. (1944). The Dream of Descartes.

Mashman, V. (2020). The Story of Lun Tauh, “Our People”: Narrating Identity on the Borders in the Kelabit Highlands. 10.20495/seas.9.2_203.

Pitchfork (2017). Why Burial’s Untrue Is The Most Important Electronic Album of the Century So Far

Salter, A. and Alexy, O. (2014). The Nature of Innovation. In M. Dodgson, D.M. Gann and N. Phillips (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Innovation Management (pp. 26–49). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schumpeter, J.A. (1942). Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, New York: Harper and Brothers.

Solomon, L & Baio, C. (2020). “An Argument for an Ecosystemic AI: Articulating Connections across Prehuman and Posthuman Intelligences”. Int. Journal of Com. WB 3, 559–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42413-020-00092-5

Veal, M. (2017). Dub : Soundscapes and shattered songs in jamaican reggae.

Whiteley, S; Rambarran, S (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Music and Virtuality. Oxford University Press. p. 412.