Mutation Space

Mutation Space is a new computer / video Installation developed in 2014.

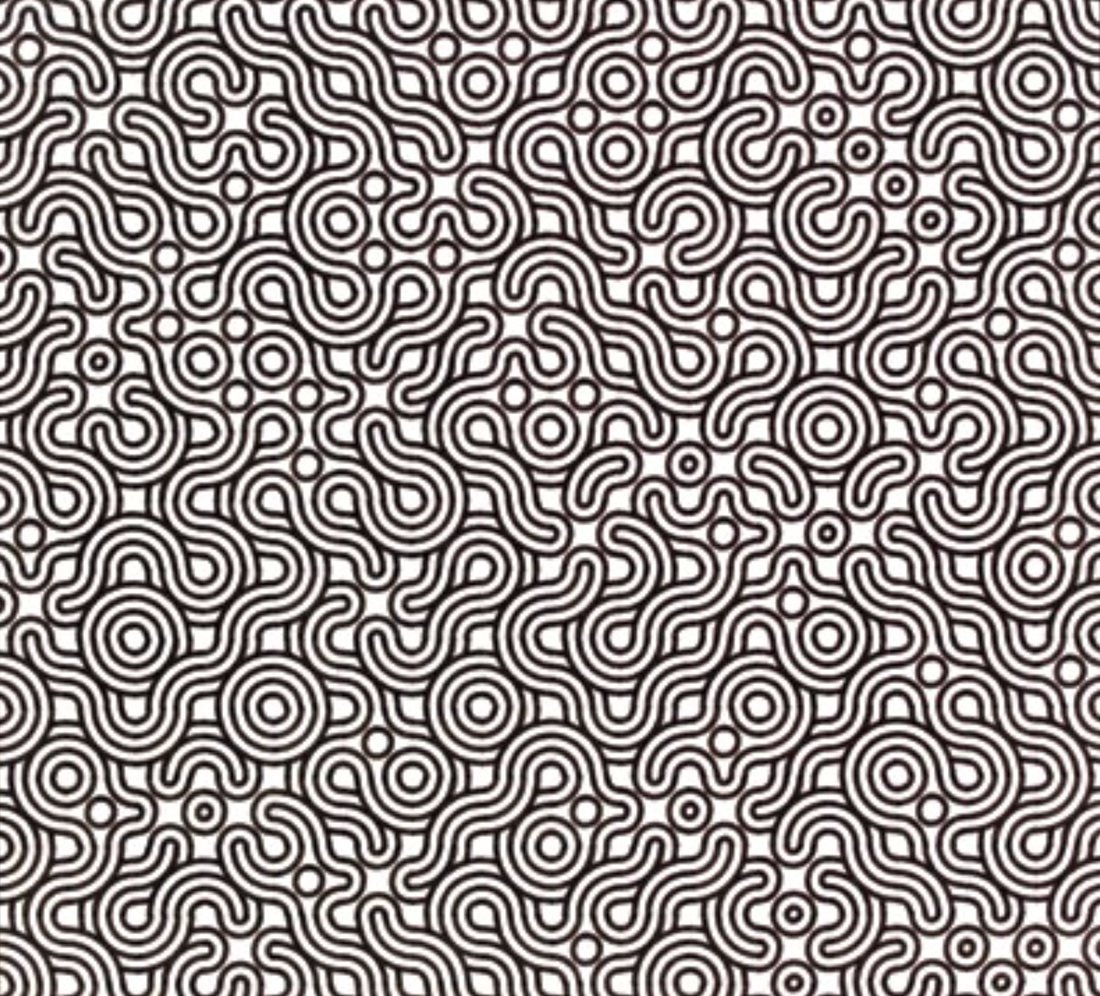

Using software modelled on the processes of evolution, it blends organic imagery and computer animation. The work includes large-scale printed translucent curtains and printed metal floor tiles which create a visually rich 3D design space within which human and machine interact.

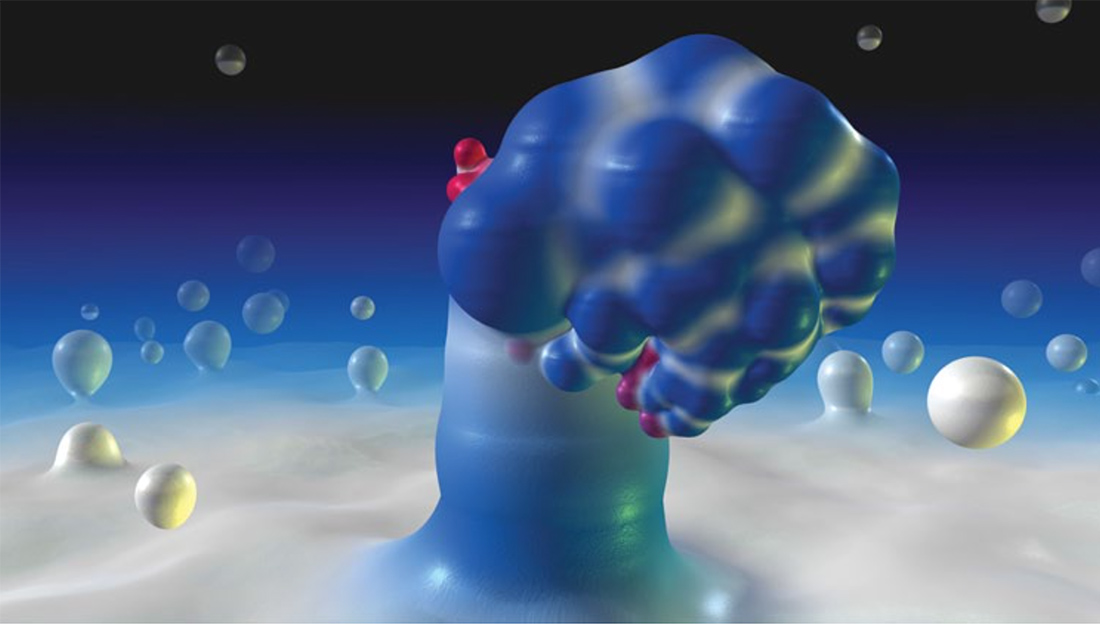

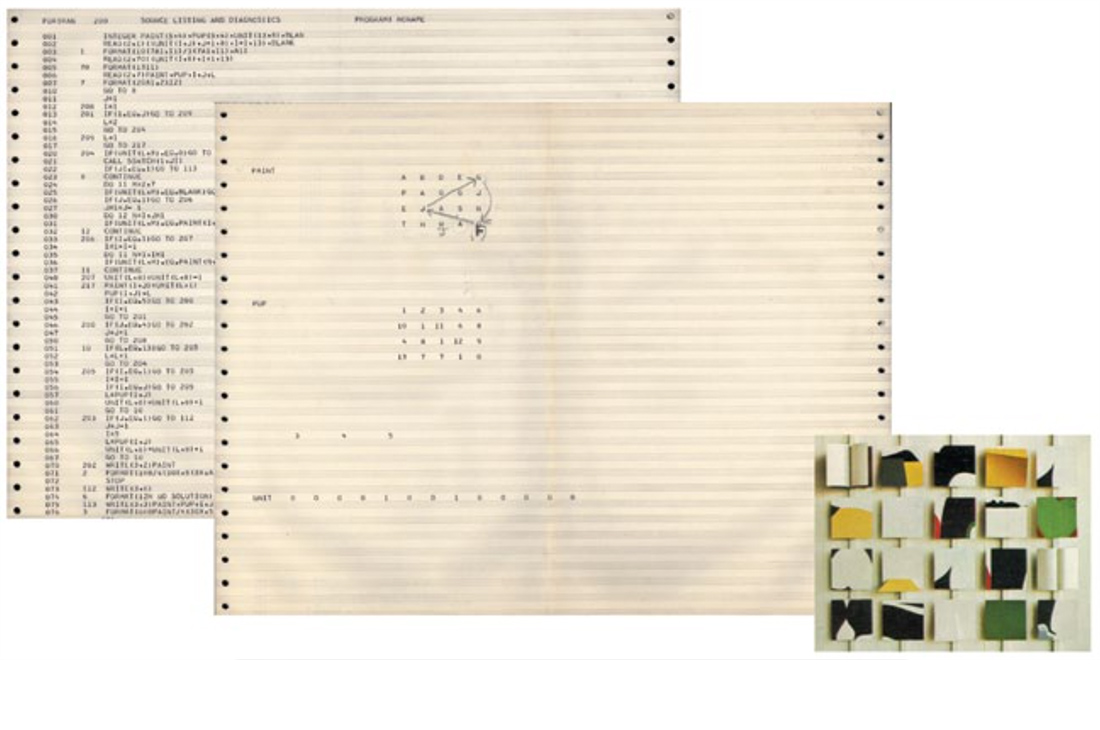

Through computer touch screens and Kinect input, viewers are able to shape and mutate vibrant mutating organic forms in real time on a large projection screen and on small computer screens. Starting with a simple horn-like form, the Mutator2 code introduces random ‘mutations’ in order to generate increasingly complex three-dimensional creations that resemble fantastical, futuristic organisms, by a process that Latham describes as “evolution driven by aesthetics”. These creations, like the Rorschach ink blot test, are open to multiple interpretations, as the viewer perceives content emerging from the endlessly mutating variations, some forms resembling Giger-eque ancient fossils, some looking like protein molecules, others like heavy metal structures and others resembling Escher-like alien spaceships. The installation includes very recent work with Stephen and Peter Todd and Lorenzo Ciciani in which the computer generates mutated variants which are then automatically culled

by the computer based on aesthetic rules that are mathematically defined, removing the need for the artist or public viewer to steer the evolution. The work reflects the artist’s long-term interest in harnessing basic evolutionary processes for creative ends.

The work is a result of William’s long-term collaboration with Stephen and Peter Todd since the late 80s and includes very recent work on Fractal Mutation and aesthetic rules by his postgraduate student Lorenzo Ciciani. Darren Cleary worked on textiles and tile production.