The Narrative principle of Cinematic Virtual Reality

produced by: Andi Wang

Introduction

The emerging virtual reality (VR) industry has gained widespread attention in recent years. Some film festivals have also set up a VR film award proving that VR film has become an accepted category in the film industry. However, it seems that the public is neither receptive to nor satisfied with the cinematic VR experience. Furthermore, directors have also encountered considerable problems when producing VR films. One of the biggest challenges is that the storytelling principle is significantly different to the traditional method. As there are already a lot of existing theories regarding VR, this report aims to explore the practical storytelling approach of Cinematic Virtual Reality (CVR) and a tool called a CVR simulator that has been created to bridge the gap between the theoretical approach and practical use.

The purpose of CVR is to present a better effect and to offer an improved sensory experience. Vision, as a dominant sense, is the key to shifting consciousness from physical reality to the virtual world. According to a study comparing the emotional effect of CVR with that of traditional 2D films, the majority of emotions are felt more in the use of CVR (Ding, Zhou and Fung, 2018). Therefore, this report combines the theory of traditional narration, psychology and philosophy in VR, analyze the relationship between the point of view of camera angle and audience feeling. As a result, an artefact called CVR simulator is designed in order to reflect the theory.

Literature Review

Virtual reality is the combination of ‘virtual’ and ‘reality’. The digital witness theory argues that VR is a technology that can shorten geographical distance and bring you closer to distant objects. However, it can also be ‘easily exploited, misinterpreted and hijacked by powerful actors’ (Awan, 2016). The aim of CVR is to immerse an audience in a 360-degree synthetic world experience (Mateer, 2017). As a film category, CVR is more than just a 360-degree video, however, when considering CVR as a part of wider VR, it can be considered to have limitations in terms of interactivity. It is notable that immersive theatre has the ability to create a similar experience to CVR. John Dewey, who was the first person to propose the theory of and design the aesthetics of immersive and interactive theatre, claimed that it is the experience that leaves a lasting impression on visitors rather than the image of the object itself (Dewey, 1930). Several immersive theatre productions have been created based on this theory. For example, Sleep No More, an award-winning production based on the story of Willian Shakespeare’s tragedy Macbeth, allows the audience to explore their own journey in a seven-storey building (Punchdrunk, 2011).

Linear and non-linear storytelling are important narrative techniques in film and literature, but they are also suitable in CVR. ‘Nonlinear storytelling occurs when narrative events are portrayed out of chronological order or in ways such that the events don’t follow a structure where effects are the direct result of causality’ according to John Bucher, an award-winning writer and also a regular contributor to VR storytelling and VR filmmaking. Bucher suggests that even when a story is told in non-linear narratives, it still abides by the linear logic. He insists, when designing an immersive experience, that ‘those inherent elements in our (audience) psychology that are needed to even engage an experience.’

As mentioned previously, this study will focus its discussion through the camera angle, meaning it is necessary to introduce the classification of the camera view. In this study, the first- person point of view refers to the audience experiencing the movie through the eye of the main character. The third-person point of view ‘clears that narrator is an unspecified entity or an uninvolved person who conveys the story and is not a character of any kind within the story, or at least is not referred to as such’ (Ricoeur, 2012). The third-person view can be divided into ‘third-person limited’, ‘third-person multiple’ and ‘third-person omniscient’. ‘Third-person limited’ refers to experiences where the audience is following only one character while ‘third- person multiple’ allows the audience to follow multiple characters (Bucher, 2018). ‘Third-

person omniscient’ refers to experiences where the narrator knows everything and the narration is not limited only to what one character knows.

Discussion

Before starting the discussion, it is important to note that designing a CVR piece is not the same as designing the narration or storyline of a traditional 2D film, but instead revolves around designing an immersive experience. Also, the CVR experience is also not the same as the VR game experience, as it only allows limited or even no interaction within the whole experience. Interactive narratives will be mentioned in this article but will not be analyzed.

Observer or Participator?

As a consequence of the method of presentation, the audience remains nothing more than the audience during the whole experience, although the point of view can shift to a particular character’s view and audiences can experience the body of the character. However, the audience can also be participants provided the experience as a whole does not disobey the notion of CVR. The 1985 Tony Award for Best Musical, the Mystery of Edwin Drood, required the audience to vote on who would kill the key character which resulted in seven different possible endings. This format makes the audience a participant and affects the ending, yet is still considered as CVR. If this were considered from a first-person view, the audience would be considered to be a character, making the audience an active participant in this project.

To consider this question from a philosophical angle, as Danaher points out, in such a scenario the ‘apple’ clearly exists in some form.(Danaher, 2017) It is not a mirage or a hallucination. It really exists within the virtual environment. But its existence has a distinctive metaphysical quality to it. It does not exist as a real apple. You cannot bite into it or taste its flesh. Nonetheless, it does exist as a representation or simulation. In this sense, it is somewhat like a fictional character. In other words, when we put on a VR headset and engage with a VR film, our perceptions of reality are altered, our consciousness has shifted to a virtual world that may be indistinguishable from our own. VR headsets allow the users to experience the sights and the sounds of the world around them, but the human brain still gives it spatial importance. The brain is aware that every time we put on the headset, we are intentionally switching realities, hence why it is called virtual reality.

First Person Angle versus Third Person Angle During the Whole Experience

It seems that CVR has an awkward position between the Cinema and VR fields. It cannot be analysed as a film in the same way as a traditional film due to the different methods of creation. Yet if we consider CVR as a branch of VR, it is viewed to offer limited audience interaction in the virtual space. Therefore, CVR is better to be seen as an independent category. Currently, it

resembles the format of immersive theatre, which allows the audience to choose their storyline but remain the audience; observing the story but not being an active protagonist within the story. For example, Sleep No More is the most suitable production to be filmed in VR, as the audience’s position is a typical third-person angle. The audience remains in the role of the audience and stays outside of the storyline, even though the characters will choose some ‘special audience’ member to perform the hidden storyline. CVR differs from immersive theatre as it allows the audience to observe the story through other positions that would be impossible in the real world. You can focus the camera on an object or a character in the story. According to the embodiment illusion theory, once the audience has the same view and even the same body as a character, we expect that the audience to be able to share the consciousness or identity of the virtual character. However, according to Christian Pfeiffer, ‘self- identification does not depend on the experienced direction of the first-person perspective.’ That is to say, the audience will never feel the same and react the same as an uncontrollable character whilst they share their perspective.

Lanier (2018) states that ‘your input in VR is you’. When designing the experience, the key is to consider the whole experience through all the sensations that can be enabled in VR. There are several conditions that are supposed to affect the whole experience. First of all, the initial location from where the audience was transferred plays a vital role in the whole experience. Pfeiffer (2013) states that ‘Self-identification does not depend on the experienced direction of the first-person perspective, whereas self-location does.’ When an audience member puts on the VR headset and is transferred from the real world to the virtual world, they will normally look around and try to figure out where they are and what should they do. Therefore, the director needs to consider the reason for the audience’s presence in that specific environment. Furthermore, the audience must have something to focus on. Once the audience becomes familiar with the environment and the surroundings, the place illusion is activated. The next step is to enable the plausibility illusion which means the audience needs to be notified as to what is happening in this scenario. The setup of one key element or event in a scene is likely to keep the audience’s attention engaged. This is because the human eye can recognize a key object quickly and follow its movement. This process will provide a natural and fluent plot for the story. Due to all the information in VR mainly being delivered by vision, these essential conditions are able to be reflected and explained by the camera angle.

The camera position is closely related to the method of narratives. The ‘third-person limited’ is a suitable approach for a narrative with a linear storytelling method because it does not alter the camera focus. That is to say, the role of the audience is decided at the beginning and remains consistent throughout the whole experience. If the role of the audience changes, the audience may become confused about their identity in the virtual space. However, this does not mean that the ‘third-person multiple’ is a worse option. In fact, the use of ‘third-person multiple’ is more appropriate for a non-linear narrative than the use of the ‘third-person limited’. However, there are less scene changes than in a traditional 2D film.

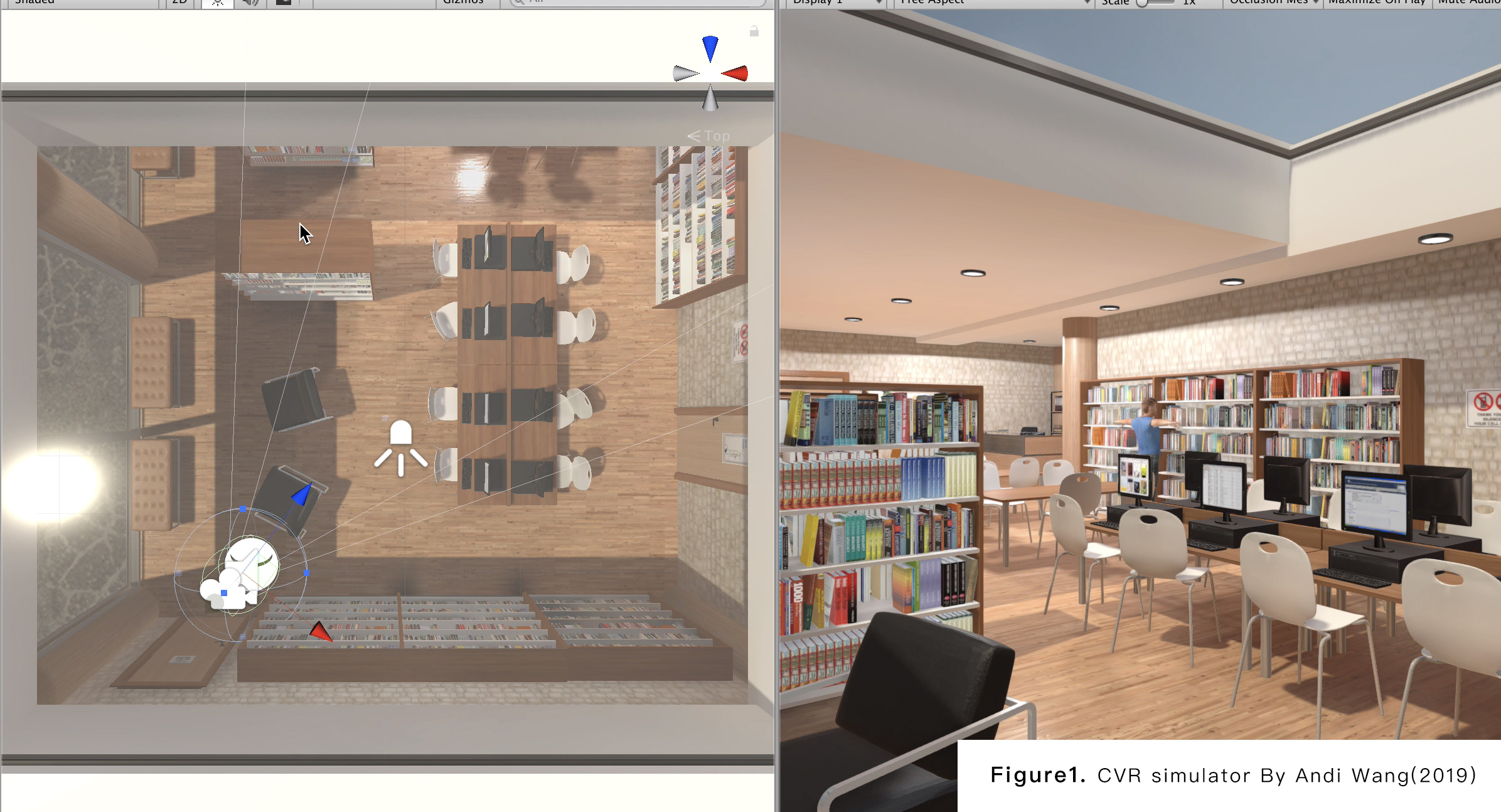

The most reliable and intuitive method to bridge the gap between the theory and practical use is to experiment and rehearse in the real world as much as possible. The CVR simulator is a system that has the ability to simulate all the camera views mentioned above and is designed to serve the creative team’s testing needs. Whilst there is no right or wrong camera view, only the most suitable camera position should be used in each story, meaning the director needs to conduct user testing as much as possible. To meet this requirement, the simulation system is able to adjust the camera angle and position, simulating the experience and providing an accurate measure for the volunteers and the production team. Compared with the real user testing process, this simulator is an economical and efficient system. The video is currently a prototype in the conceptual level.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the key to designing a CVR narrative is to rely on the logical processes of the designing experience. Immersive theatre is similar to the CVR experience as they both regard the audience as both observers and participants at the same time. The camera, which acts as the eye of the audience, is the essential media for shifting an audience member’s consciousness from the real world to the virtual world. The camera position needs to be carefully selected because it can provide different emotional perspectives during the experience.

The camera focus could be divided between the ‘first-person view’, ‘third-person limited’ and ‘third-person multiple’. It is expected to offer different experiences and emotionally affect the audience. Camera positions are chosen depending on the content of each individual CVR experience. The CVR simulator reflects the camera position, illusions and the experience. It allows the director to simulate all the camera positions mentioned in this article and achieve

the goal of combining theory and practical use. Furthermore, it provides more possibilities when designing a CVR experience, as directors can carefully choose the camera position before they continue to the filming process.

References

Awan, N. (2016) ‘Digital Narratives and Witnessing: The Ethics of Engaging with Places at a Distance’, GeoHumanities, 2(2), pp.311‒330.

Bucher, J.K. (2018) Storytelling for Virtual Reality: Methods and Principles for Crafting Immersive Narratives,

The author, an award-winning writer and a narrative consultant, wrote this book to serve as a bridge for new media students seeking to become professionals in the emerging VR field.

Danaher, J. (2017) The Reality of Virtual Reality: A Philosophical Analysis. Dewey, J. (2005) Art as Experience, New York: Perigee.

Ding, Zhou & Fung, (2018) ‘Emotional effect of cinematic VR compared with traditional 2D film’, Telematics and Informatics, 35(6), pp.1572‒1579.

Gillies, M. and Pan, X. (2018) ‘Introduction to the Three Illusions - The Psychology of VR: the Three Illusions’, Coursera.

Heim, M. (1993) The Metaphysics of Virtual Reality, New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The author, known as ‘the philosopher of cyberspace’, looks into this new technology through a philosophical approach. He explores the logical and historical origins of our computer- generated world and speculates about the future direction of our computerised lives.

Henrikson, R. et al. (2016) ‘Multi-Device Storyboards for Cinematic Narratives in VR. ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology’ UIST, pp.787‒796.

Lanier, J. (2018) Dawn of the New Everything: A Journey through Virtual Reality

The author, a computer philosophy writer and founding father of the field of virtual reality, reflects his own lifelong experience with the technology. He explores and explains this technology in a poetic and romantic way, explaining how virtual reality went from a dream to reality over the last three decades.

Mateer, J. (2017) Directing for Cinematic Virtual Reality: How the Traditional Film Director’s Craft Applies to Immersive Environments and Notions of Presence, J. Media.

Pfeiffer et al. (2013) ‘Multisensory origin of the subjective first-person perspective: visual, tactile, and vestibular mechanisms’, PLoS ONE, 8(4), p.e61751.

Punchdrunk (2011) ‘Sleep No More’ — Punchdrunk. [online] Available at: https:// www.punchdrunk.org.uk/sleep-no-more

Ricoeur, P. (2012) Time and Narrative, University of Chicago Press.

Tricart, C. (2018) Virtual reality filmmaking: techniques & best practices for VR filmmakers