Pandemics and Surveillance Capitalism in Virtual Worlds

produced by: Alexander MacKinnon

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the growth of virtual presence in daily life could be said to have somewhat prepared us for the physical social distancing required over the past year during the Coronavirus pandemic. Since the 1970s, computer mediated virtual worlds have been developed and inhabited, and have been used extensively in entertainment. The pandemic has proliferated and made mainstream the adoption of 3D virtual worlds to host workplaces, social spaces, events, and exhibitions. Throughout this essay I question: what implications does the increased use of virtual presence have on human experience, socially, politically, and culturally? How are virtual worlds increasingly spaces that are targeted for corporate control?

Following the definition of a virtual world as “a shared, persistent, computer-simulated environment in which people act on and interact with others as well as artifacts through characters or avatars” (Rhoten, Lutters, 2010), virtual worlds offer an alternate space allowing for the enactment, production and exploration of plural identities outside of physical bodies and geographies. This liberating potential of virtual mediums has been praised and expanded upon by multiple Posthuman theorists and early Computer Mediated Communications studies. For example, N. Katherine Hayles seminal book How We Became Posthuman (1999) traces the technologies and cybernetic theories that led to the discourse around the “Posthuman”, developing a framework beyond liberal-humanist ideas. Likewise, Donna Haraway’s A Manifesto for Cyborgs envisions an ontology of emancipation stemming from hybrid cybernetic organisms: “the cyborg is a condensed image of both imagination and material reality, the two joined centres structuring any possibility of historical transformation” (Haraway, 1991). However, moving into the current day, the liberating benefits of virtuality and its posthuman potentials are becoming limited. As surveillance capitalism has emerged as a dominant feature of the digital ecosystem, we are seeing many shifts within mainstream virtual worlds towards surveillance and control, perpetuating extractive capitalist behaviours that data-ify as many aspects of life as possible.

In this project I will discuss the meaning of virtual worlds in relation to both the current pandemic, and the growing corporate practices in surveillance capitalism. I am specifically interested in multi-user 3D worlds which simulate a sense of presence within a social space. The first case study I wish to examine is the “Corrupted Blood Incident” an unforeseen and emergent virtual pandemic which took place in the MMORPG World of Warcraft in 2005, which epidemiologists took particular interest in as a model for pandemic spread. I will also discuss the trends of cultural spaces such as music events and art exhibitions moving into virtual spaces during the pandemic. We have seen these spaces increasingly serving as a replacement for the physical social experiences which lockdown restrictions have forced us to avoid. While the use of some of these spaces comes because of repression from physical sociality, the virtual context of these replacements greatly changes our experience of the activities they facilitate.

Corrupted Blood Incident

Fig 1. Aftermath of the Corrupted Blood incident

Following the Corrupted Blood incident, an unexpected virtual pandemic which took place in the MMOG World of Warcraft in 2005, epidemiologists Eric T Lofgren and Nina H Fefferman detailed several mirroring aspects of the Corrupted Blood incident with how epidemics unfold in the real world, pointing out the potential of similar environments in applied simulation modelling for epidemic research. They especially note that this kind of multiplayer virtual environment offers an excellent model of how human behaviours will affect a contagious disease’s spread, explaining that while simulations are now widely used in their field, they struggle to “tailor their use to incorporate human behaviours”.

At the time of the event, WOW was home to an estimated 4 million players. On September 13, 2005, a software update introducing a new boss type enemy character named “Hakkar the Soulflayer”. While players engaged with this character in combat, he cast a contagious debuff spell called “Corrupted Blood” which drained health points over time. While this spell was intended to only affect players during the encounter, it had very unexpected consequences. Lofgren and Fefferman point out that the ability to fast travel in game, allowed the debuff spell to be brought back to city areas, “mimicking the travel of contagious carriers over long distances that has been the hallmark of many disease outbreaks in history”. The disease was also unknowingly transmitted through players’ pets.

The incident featured population groups present in real-world epidemic situations - While high-level players were unlikely to die from the spell, there was an in-game high-risk population of lower levelled players that represented the elderly or immunocompromised, and Non-Player Characters (NPCs) acted as asymptomatic carriers.

Blizzard Entertainment imposed quarantine measures to isolate infected players. Lofgren and Fefferman note that “These strategies failed because of the highly contagious nature of the disease, an inability to seal off a section of the game world effectively, and more than likely player resistance to the notion”, mirroring numerous governments and societies’ attempts and failings to respond to the current pandemic.

Lofgren and Fefferman point out that importantly, the event emulated the “social chaos that comes from a large-scale outbreak of deadly disease”. They suggest that the strengths of this spread simulation model are to measure the effects of both individual and social behaviour patterns, or social organising such as medical responses.

The article highlights the significance of this event at a time when virtuality takes increasing presence and importance in our lives, being the “first time that a virtual virus has infected a virtual human being in a manner even remotely resembling an actual epidemiological event”.

Data and Privacy – the Capitalisation of Virtual Worlds

While Lofgren and Fefferman’s journal article praises the potential of using virtual worlds as scientific simulation models, it briefly points out the ethical questions around privacy and data usage consent that this practice would entail. Various researchers have been using virtual worlds to monitor users’ online actions, attempting to map connections to users’ real-world personalities and behavioural tendencies. This is discussed by Nicolas Ducheneaut (2010), who compares Massively Multiplayer Online Games to “living laboratories” and has been “engaged for several years in intensive data collection in several MMOGs” at the Palo Alto Research Center.

Ducheneaut states that “the digital nature of these social spaces makes them particularly amenable to large-scale, automated data collection and analysis”. This opens the questions of who has access to a virtual world’s data, and what are they doing with it? Ducheneaut points to the companies that own these worlds - they hold the key to vast amounts of user data and view it as a precious business asset. Their servers allow them to map between a user’s virtual character and real socio-demographic information.

It seems that there has been an ideological shift from virtual worlds as liberating safe spaces for identity exploration towards more capitalist minded worlds centred around surveillance and control. Multi-User Dungeons, the origin of virtual worlds, were predominantly run by hobbyists or academic institutions, however now the mainstream Games-as-a-Service business model which profits from maximising in-game sales of virtual goods creates idealised capitalist environments which encourage exploitative data practices.

Stafford (2019) points out that it has now become common practice for game developers to collect behavioural data from their players. In her Game Developers Conference talk, Emily Greer, the CEO of game publisher Kongregate, reflects the view of users’ behavioural and socio-demographic data as a business asset (GDC, 2020). While Stafford (2019) discusses the potential of this information to help create better user experiences, and Lofgren and Fefferman see it’s practical application for social and medical science, many companies share Greer’s perspective: User data as a tool to be capitalised on, effectively reducing users' personality and behavioural tendencies down to systems to exploit and control.

Virtual Worlds exist against an increasing backdrop of integrated platforms and smart devices that collect data for corporate interest. This practice pushes our society towards increasingly unbalanced power structures between the surveillance capitalists and the surveilled. Shoshana Zuboff (2019) states “As long as surveillance capitalism and its behavioural futures markets are allowed to thrive, ownership of the new means of behavioural modification eclipses ownership of the means of production as the fountainhead of capitalist wealth and power in the twenty-first century”. While Zuboff points out Google as the proprietary instigator of many of these strategies, Amazon is another prime example of how data surveillance leads to corporate control.

Amazon, which is already the dominant web service provider, launched Amazon Game Studios in 2012. Schrier and Anand (2021) report that although they have worked on a series of failed projects, Amazon Games are aiming to manufacture large, ambitious virtual worlds to “draw gamers into the Amazon Prime ecosystem and showcase the technical capabilities of its cloud division”. Amazon Games would serve as an extension of the company’s behavioural data collection web. Schrier suggests that the company founder Jeff Bezos “views games as yet another way to sell subscriptions to Prime and hook customers on its other offerings”.

Not only is virtual world data being used within their own realms – Stafford (2019) points out the real-world implications that virtual world behavioural data is starting to have. He explains that this data can be used to build robust personality profiles. For instance, China’s social credit system considers user’s time spent playing video games, a factor then used to make real-world personality assumptions. While Stafford writes that this data is predominantly used for targeted advertising, he passes on the warning from privacy experts that this data has the potential to be used in sinister ways.

Culture shifting into Virtual Spaces

Since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, we've seen a significant increase in inhabitation of virtual spaces. Şener et al (2021) report that significant increases in active videogame players have been observed since the start of the pandemic, with gaming platforms seeing record usage and financial growth. Şener et al suggest that the videogame industry’s success is due to the medium being accessible from home and affordable compared to other entertainment forms - as is the case with other non-game virtual worlds which are seeing growing userbases. Under lockdown restrictions these worlds are serving as replacements for work, social and cultural spaces.

The social VR app VRChat has seen record usage during the pandemic (Lang, 2020) and the long-standing virtual world Second Life has experienced a 60% surge in new account registrations (Linden Lab, 2020).

Fig 2. Peale Museum in Second Life

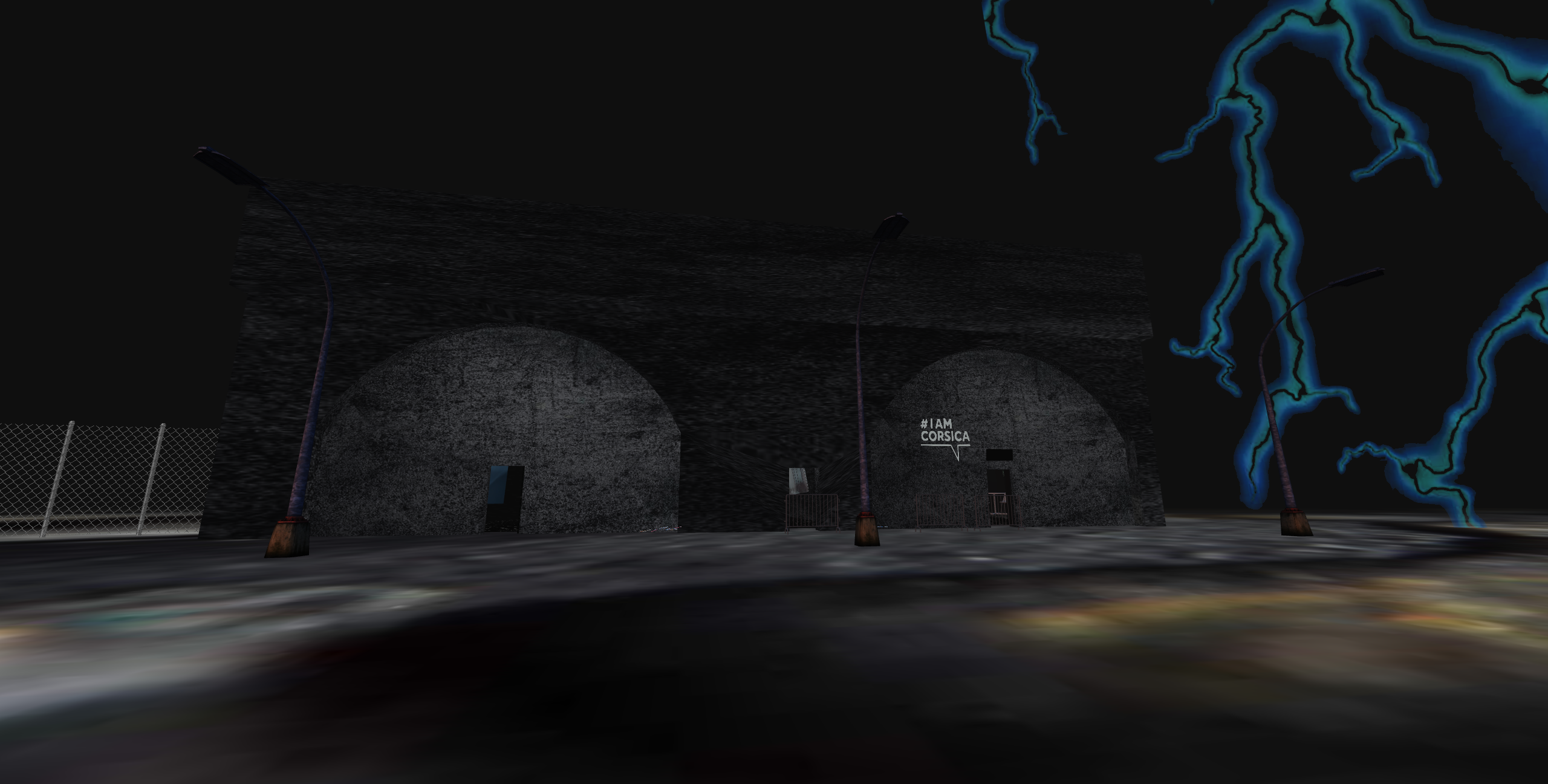

Many cultural spaces have moved into virtual worlds – there has been a plethora of virtual art exhibitions hosted in online worlds such as those facilitated by Mozilla Hubs or New Art City. Both platforms support multi-user rooms, with social functionality such as text chat and seeing users' avatars. Corsica Studios, a London underground music and arts venue, explains “With the clubbing scene dead for over a year, reimagining the creative potential for our deserted nightlife spaces seems fitting right now”. Corsica Studios launched its virtual world arts program Schemata on New Art City, starting with their current exhibition, Vortex (2021). The program features a virtual recreation of their London club space in which visitors can listen to live DJ sets with viewing rooms for artworks.

Fig 3. Corsica Studios’ virtual space

Carmo and Claudio (2013) describe the ability for simultaneous visitors worldwide to experience artwork in virtual museums and galleries in real-time, when there are physical constraints to visiting in person as “a democratic cultural achievement”, praising these virtual exhibition spaces for the accessibility that they offer.

While virtual worlds are helping to make cultural spaces remotely accessible, the continued shift of arts, music and social spaces into virtual worlds, comes with a danger that surveillance capitalist practices will take an increased presence into those spaces.

Conclusion

Whilst digital simulation is common practice in scientific modelling, we are witnessing the beginning of a growing tendency for those in power to enact real world social manipulation through digital data. Early internet and virtual world ideologies were underscored by the goal of liberating information flows, and increased connectivity. Today, researchers are increasingly interested and engaged in data collection from virtual worlds, as the digital nature of these worlds makes them optimal targets for surveillance.

As more aspects of life and culture move into virtual worlds, a process greatly accelerated during the Coronavirus Pandemic, we should be increasingly weary of manipulative data practices conducted by the companies that own them. We have already seen the potentials of population control through data mining during the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal (Cadwalladr, Graham-Harrison, 2018). This leads to the question of what could be achieved with data from virtual worlds, spaces which allow much richer user interactions, and therefore richer data to manipulate?

Beyond the concern of virtual spaces granting access to increased levels of data, targeting them for extraction also invites surveillance into intimate expansions of personality in an alternative space that might have been regarded as liberating. As Lofgren and Fefferman write “many players strive to create a believable alter ego in the virtual world, complete with the weight of responsibility and the expectations of others... Research into the behavioural and emotional involvement of game players, and their relationship with their virtual selves has shown that reactions to events in the game world can have serious, emotional repercussions.”

Furthermore, Ducheneaut suggests that “While play is often derided as less important than work in the study of human behaviour, ethnographic studies of the social life of guilds clearly show that participating in them actually requires significant efforts to solve problems that are not entirely different from those encountered by groups in other, less playful contexts”. He makes the comparison of duties towards one's in-game social group to a form of labour and social commitment. The level of commitment and attachment people feel towards their virtual characters and their communities in virtual spaces will result in people’s virtual reactions approximating reactions to real dangerous situations. This sentiment of commitment towards virtual entities is especially emphasised now that virtuality is serving as a replacement to physical social interaction due to the pandemic. Manipulating virtual society is a direct manipulation of real-world relationships.

References

Cadwalladr, C., Graham-Harrison, E. (2018) ‘Revealed: 50 million Facebook profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach’, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election

Ducheneaut, N. (2010) ‘Massively Multiplayer Online Games as Living Laboratories: Opportunities and Pitfalls’ in Bainbridge, W.S. (ed.) Online Worlds: Convergence of the Real and the Virtual. London: Springer

Game Developers Conference (2020) Data-Driven or Data-Blinded? Uses and Abuses of Analytics in Games. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MR2rorssk9c

Haraway, D.J. (1991) ‘A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century’ in Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge.

Hayles, N.K. (1999) How We Became Posthuman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lang, B. (2020) ‘Social VR App ‘VRChat’ is Seeing Record Usage Amidst the Pandemic’, Road To VR. Available at: https://www.roadtovr.com/vrchat-record-users-coronavirus/

Linden Lab (2020) Second Life in 2020: Year in Review. Available at: https://community.secondlife.com/blogs/entry/6811-second-life-in-2020-year-in-review/

Lofgren, E.T., Fefferman, N.H. (2005) ‘The untapped potential of virtual game worlds to shed light on real world epidemics’, Personal View, 7(9). Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(07)70212-8/fulltext

Rhoten, D., Lutters, W. (2010) ‘Virtual Worlds for Virtual Organising’ in Bainbridge, W.S. (ed.) Online Worlds: Convergence of the Real and the Virtual. London: Springer

Schemata: Vortex (2021) [Exhibition] New Art City. 26 March 2021 – current. Available at: https://newart.city/show/corsica-studios

Schreier, J., Anand, P. (2021) ‘Amazon Can Make Just About Anything—Except a Good Video Game’, Bloomberg. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-01-29/amazon-game-studios-struggles-to-find-a-hit

Şener, M., Yalcin, T., Gulseven, O. (2021). The Impact of Covid-19 on the Video Game Industry. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348448520_The_Impact_of_Covid-19_on_the_Video_Game_Industry

Stafford, P. (2019) ‘The dangers of in-game data collection’, Polygon. Available at: https://www.polygon.com/features/2019/5/9/18522937/video-game-privacy-player-data-collection

Zuboff, S. (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. London: Profile Books.

Images

Figure 1. Aftermath of the corrupted blood incident. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/abacus/games/article/3047267/wuhan-coronavirus-prompts-netizens-study-world-warcraft-epidemic

Figure 2. Screenshot from my visit to the Peale Museum in Second Life, which recreated their physical museum during lockdown.

Figure 3. Screenshot from my visit to Corsica Studios’ virtual space, hosted on New Art City