Ark

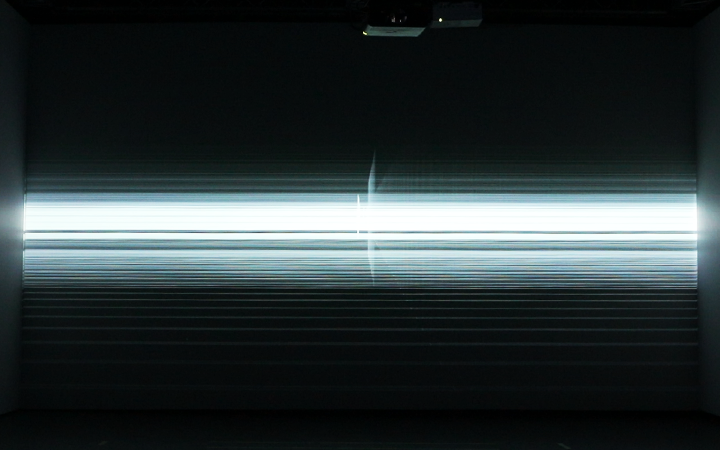

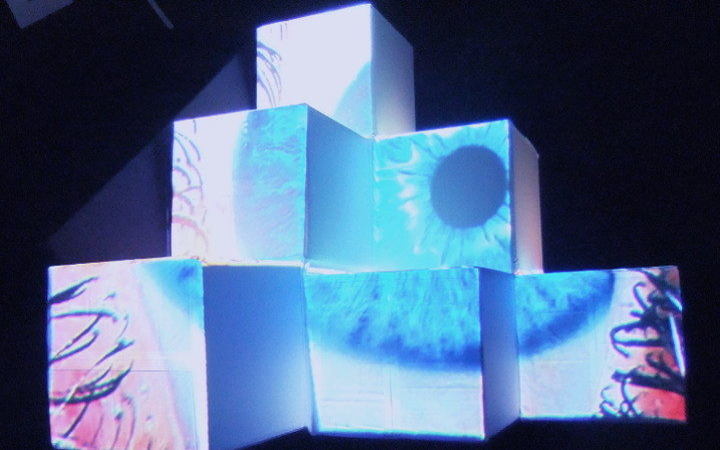

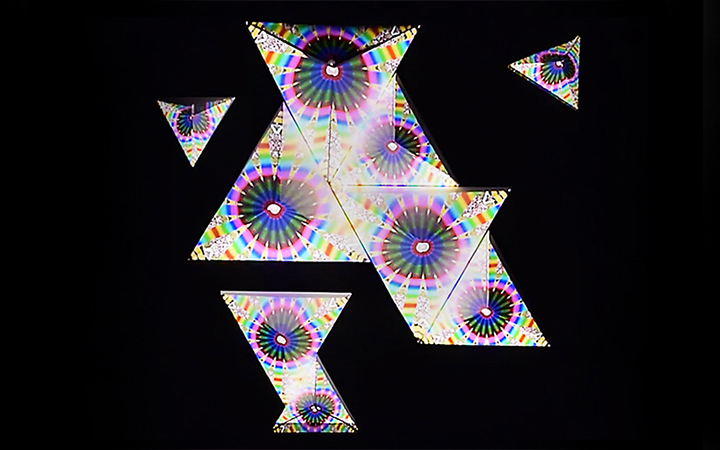

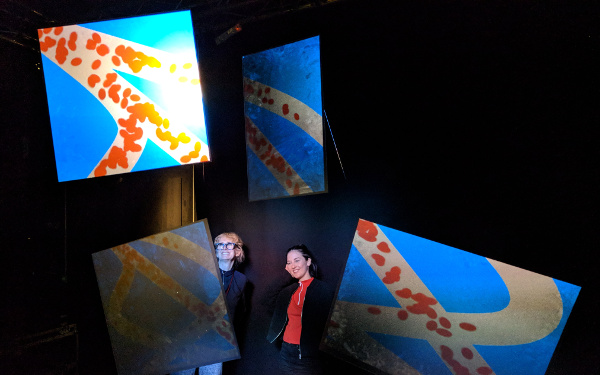

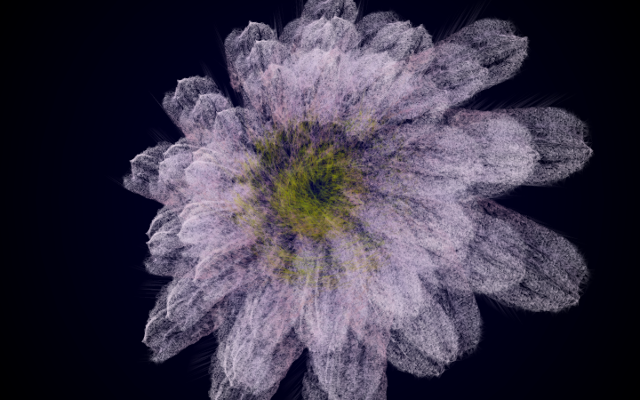

Ark is an installation consisting of projected video and electromagnetically controlled ferrofluid. It explores the dual role of randomness as a creative and destructive force in systems of meaning.

produced by: Samuel Ludford

Introduction

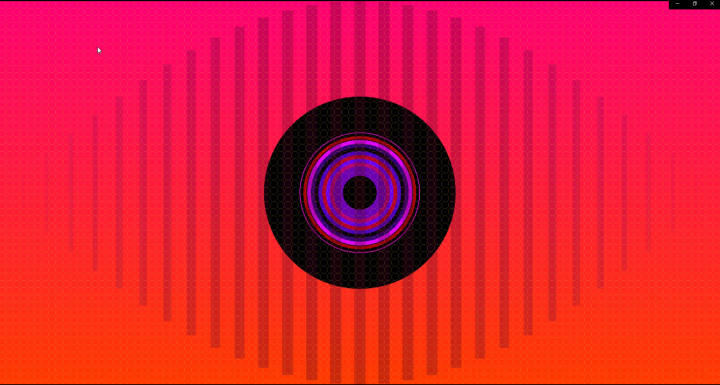

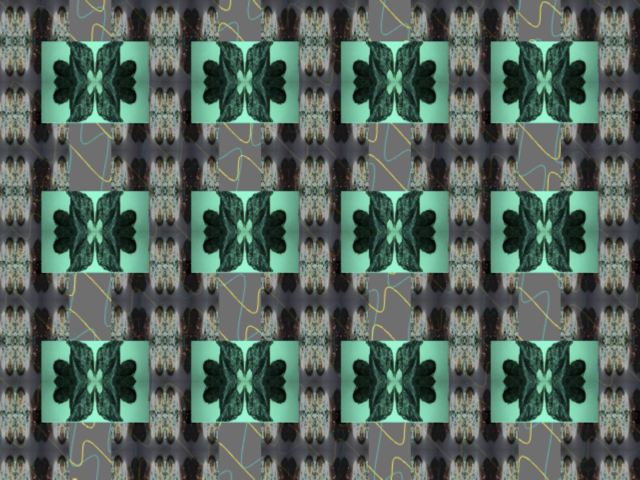

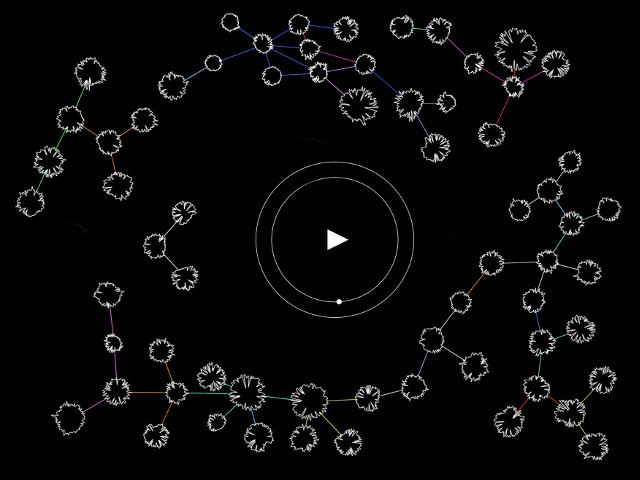

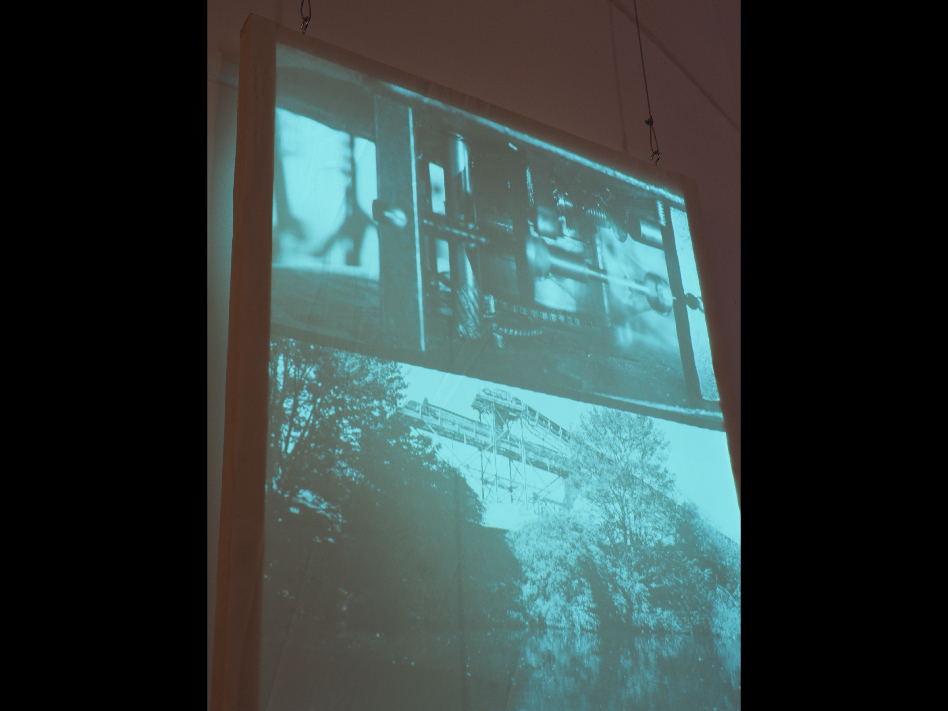

Inspired by the Tarot, Ark explores the human tendency to read patterns and narratives into random permutations of symbolic systems. A deck of twenty film clips containing resonant motifs from the post-industrial landscapes are computationally shuffled using random number generators, reinforcing some associations while weakening others.

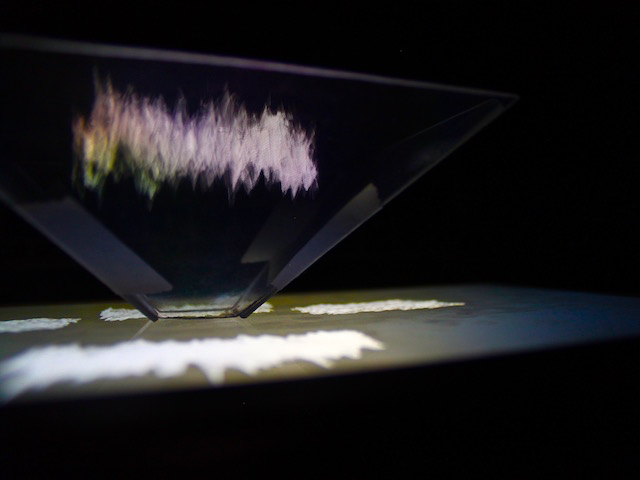

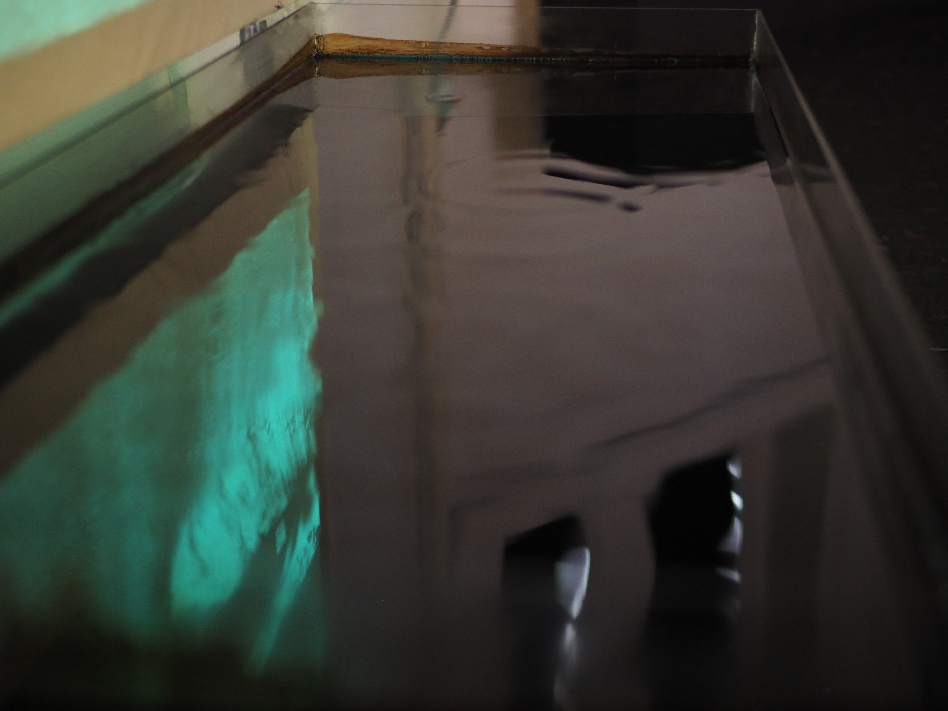

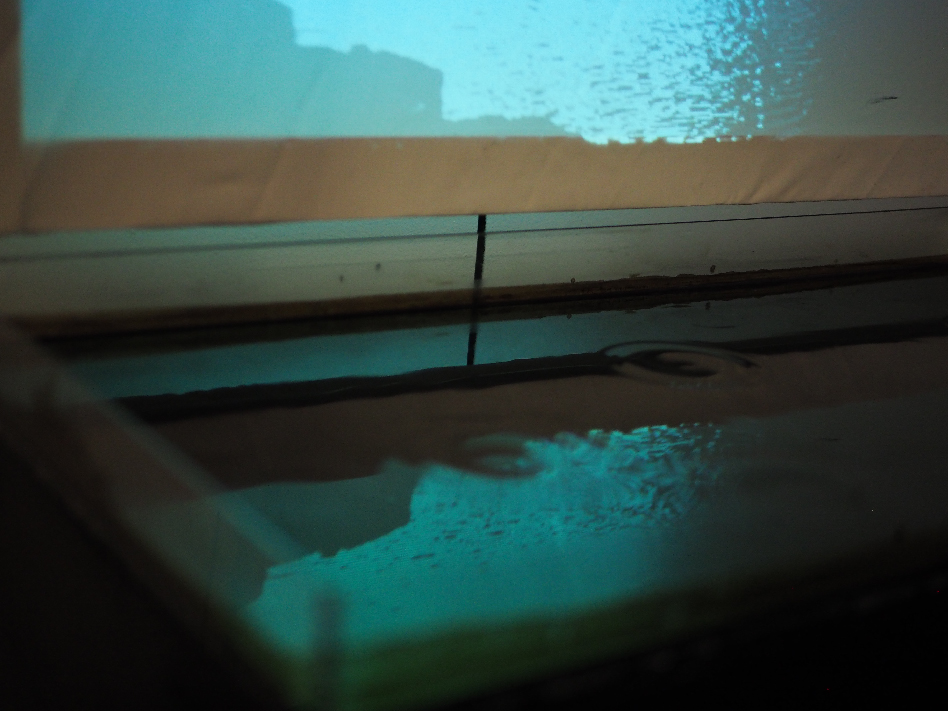

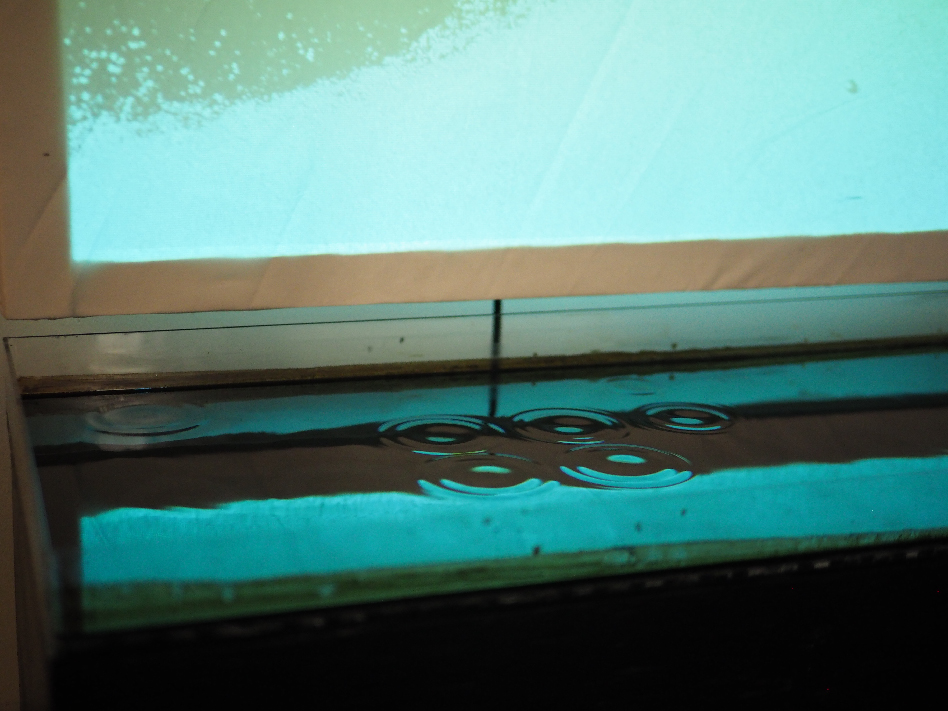

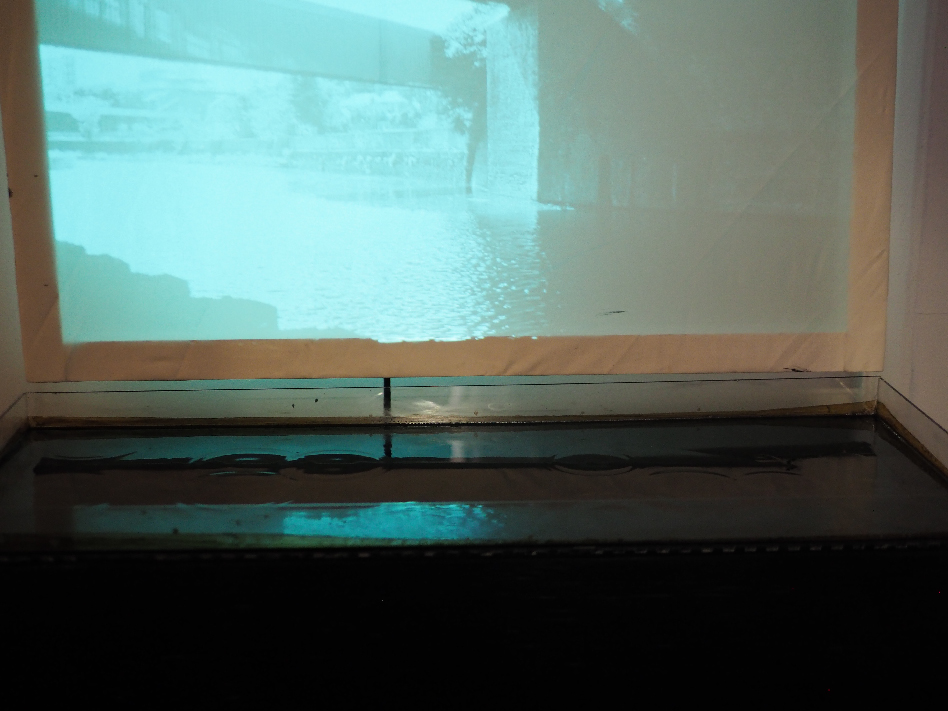

Below the image is a pool of ferrofluid whose motion is manipulated via the random pulsing of electromagnets beneath it, giving the impression of raindrops or bubbling oil. The image is reflected on the surface of the liquid and distorted by its motion. The double layering of randomness creates a system in which images of machinery, fluidity, and material recur and recombine in both image and the medium through which it travels.

Concept and background research

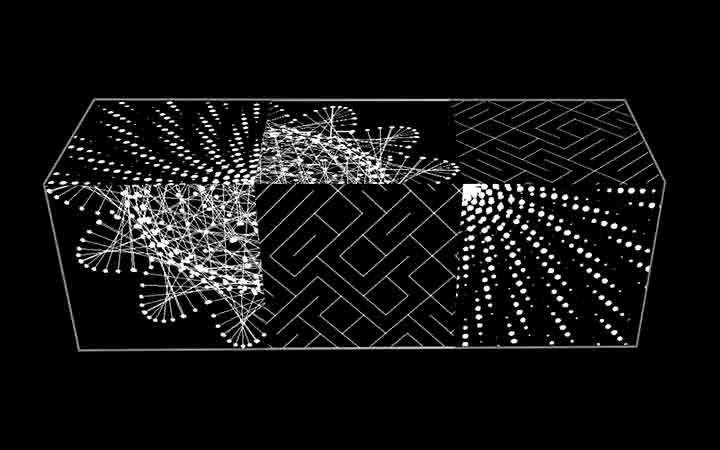

In much of my work this year I have been interested in closed systems, in which technological components interact with and for each other. (e.g. Interagency [1], Prima Materia [2]). This has raised questions about how the human viewer relates to artworks of this kind. This question formed the departure point for Ark. I wanted to expand the notion of a closed system to include a human components, not as viewers, or passive observers, but as constitutive functional parts of the system itself.

It was important to avoid ‘interaction’ in the common sense of the word, i.e. via some kind of predefined interface, such as buttons, touch screens, computer vision, etc. It seemed to me that these kinds of interface serve as abstraction layers, separating the two sides of the system—viewer and artwork. This is precisely the separation I wanted to avoid; I was more interested in exploring the possibility of the viewer forming a constitutive part of an artwork composed of heterogeneous elements—human, electronic, material, symbolic, and computational—within which the relations constituting the totality are constantly being renegotiated.

A similar line of thought led me to work with randomness. For some time I have been interested in the use of divination systems in creative practices as a way of accessing novelty. Famously John Cage used the I Ching as a compositional tool, but a more direct influence on me was the use of tarot reading by the surrealist filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky [3]. According Jodorowksy’s study of the Tarot the aim is to use the recombination and permutation of an external symbolic system to access one’s unconscious mind, via a mechanism not dissimilar to projection in psychoanalytic theory. The aim is not to predict the actualities of the future, but to uncover the potentialities hidden in the present.

Two things interested me about this. The first is that according to this vision the presence of randomness in the process of reading not only does not undermine it, as a sceptic might have it, but is essential to the practice. It is because the recombination is random, and therefore unpredictable, that it can inject novelty. Randomness represents the disruption of the sphere of human consciousness by something not already contain within it.

The second was a parallel I perceive between Jodorowsky’s thoughts on the Tarot and Steven Shaviro’s exposition of accelerationism [4]. Acelerationism, in Shaviro’s version, is a stream of anti-capitalist thought which contests that the only way out is through. That is, the only forces powerful enough to overcome capitalism are the contradictions inherent to capitalism itself, so the wisest strategy for anyone wishing to overcome it should be to exacerbate those contradictions. The sense of exacerbate imagined by Shaviro is one of extrapolation, and as such he sees speculative art, particularly science fiction, as vital tools in achieving this. By working through the long-term implications of forces at work in society now, speculative art can bring us into contact with ‘the futurity that haunts the present’, revealing alternative futures and making possible new courses of action.

What Shaviro imagines on the level of society seems to me to be similar to what Jodorowsky imagines Tarot reading to achieve at the level of the individual. For my piece I wanted to make this parallel explicit and combine the ideas.

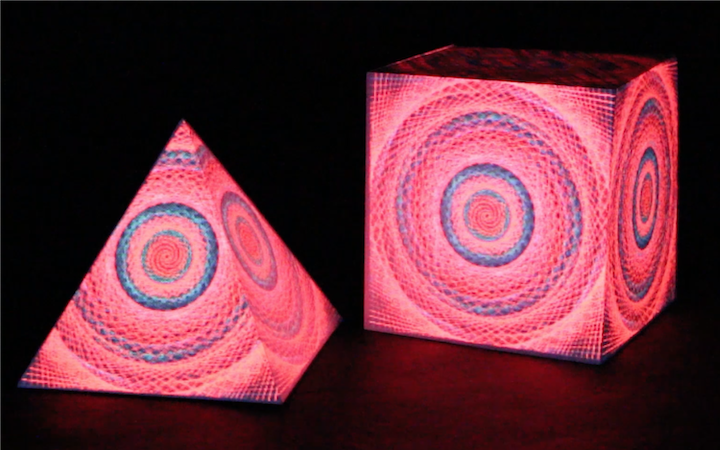

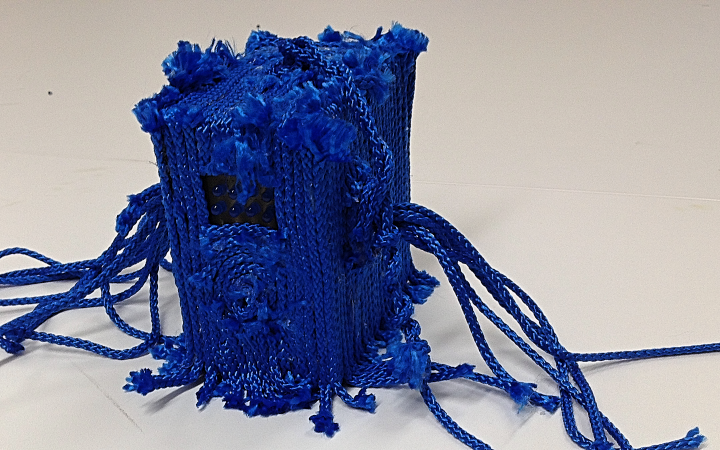

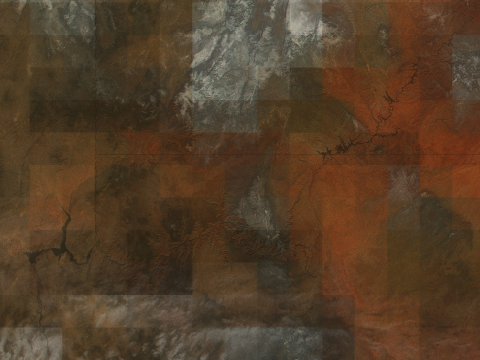

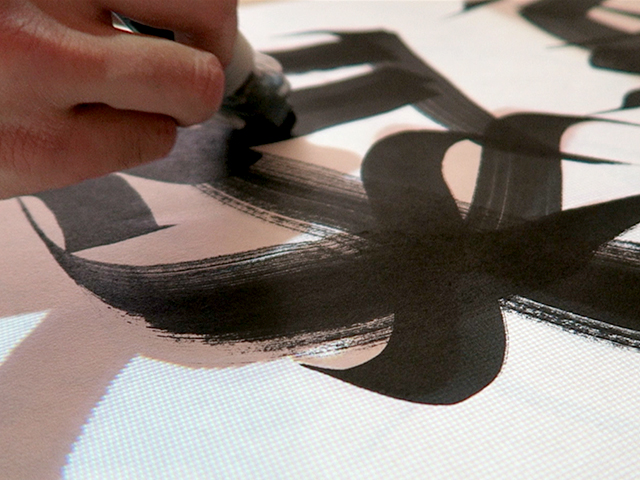

Another thread I’ve been pursuing concerns how elements of technological and post-industrial landscapes can function as vehicles for unconscious contents, thought of as analogous to religious or mythological symbols. This was something I was exploring when working with ferrofluid earlier in the year. It’s jet black colour and bubbling motion when stimulated with electromagnetic pulses make it look like a strange cousin of crude oil. In Prima Materia [5] I had aimed to make use of these associations, but felt limited by scale. I decided to work with ferrofluid on a larger scale to bring its strangeness to the forefront. I also wanted to use the reflection of a projected image to both highlight motion on the surface of the fluid and play with the notion of doubling and distortion.

For the content of the projected image I decided to create something like a Tarot deck composed of videos rather than static images. Looking for resonant images in post-industrial landscapes I shot the footage in Hackney Wick, around my house and along the canal. It felt like an ideal source for the imagery for this project, a concentrated site of social forces where the detritus of industry (past and present) is constantly being salvaged, harnessed and reassembled into new and often conflicting forms of life. My interest in these situations had been ignited and shaped by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s study [6] on the ad hoc matsutake trade which sprang up in the Oregon forests following widespread deforestation by the timber industry, and has helped me to situate the project in less critical and more constructive frameworks.

I allowed my choice of imagery to be guided by intuition as much as possible, not wanting it to be too consciously assembled. Wandering around filming I found several recurring themes emerging: the colour black, water in motion, hands, plants, circular motion, and machinery. I end up with twenty of so shots in which these motifs appear alone or in combination.

Technical

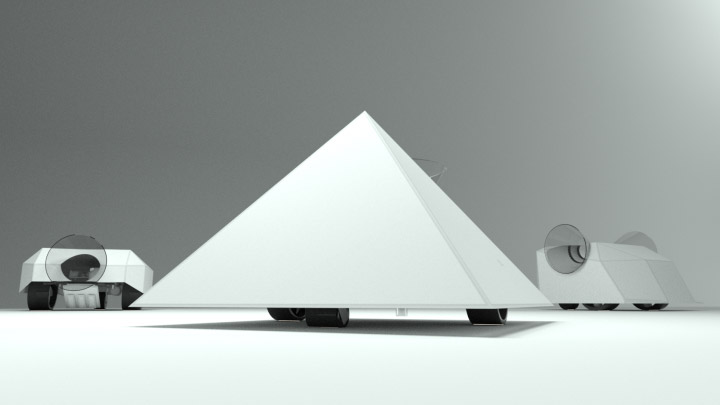

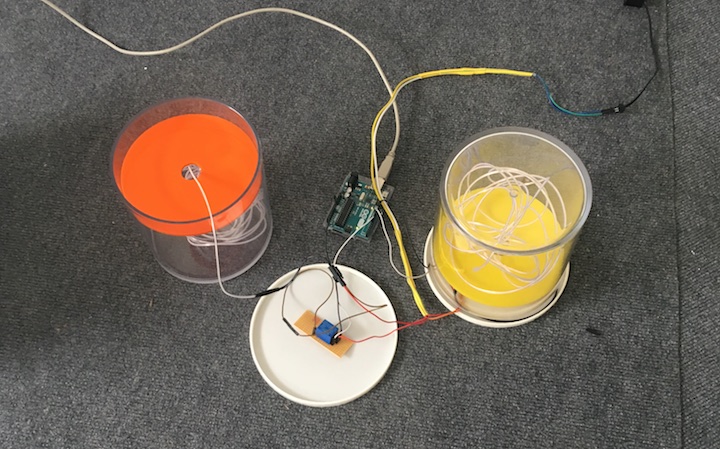

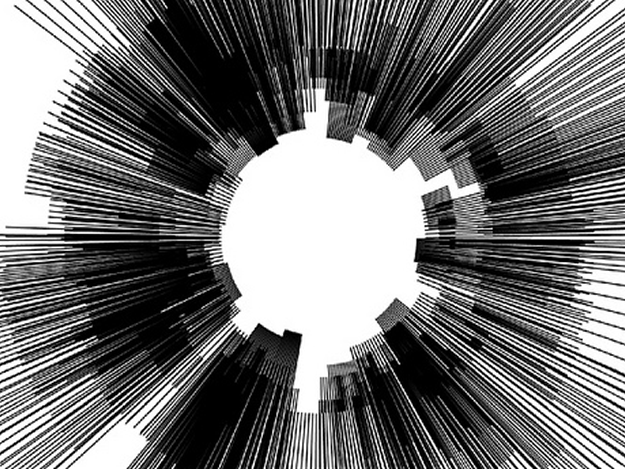

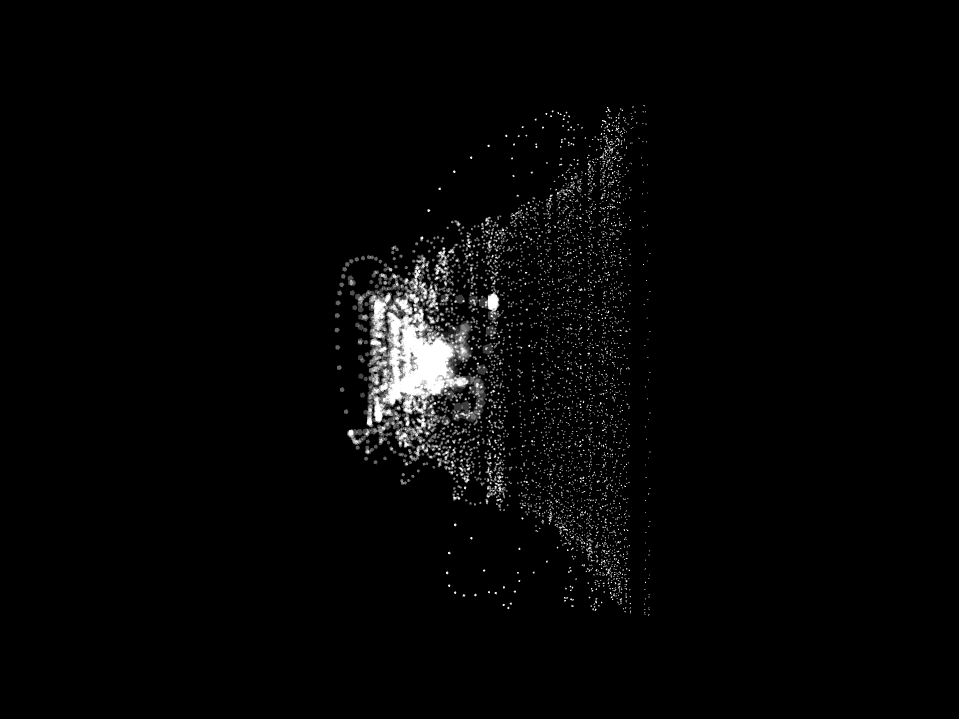

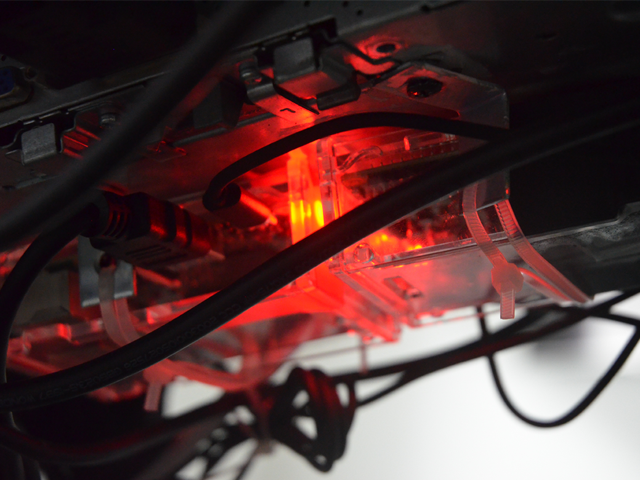

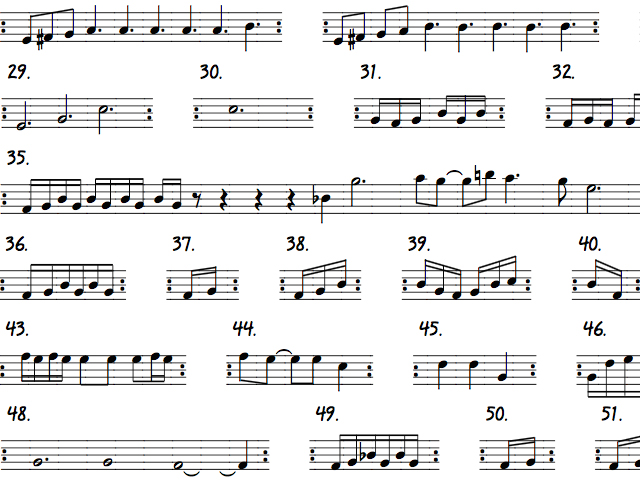

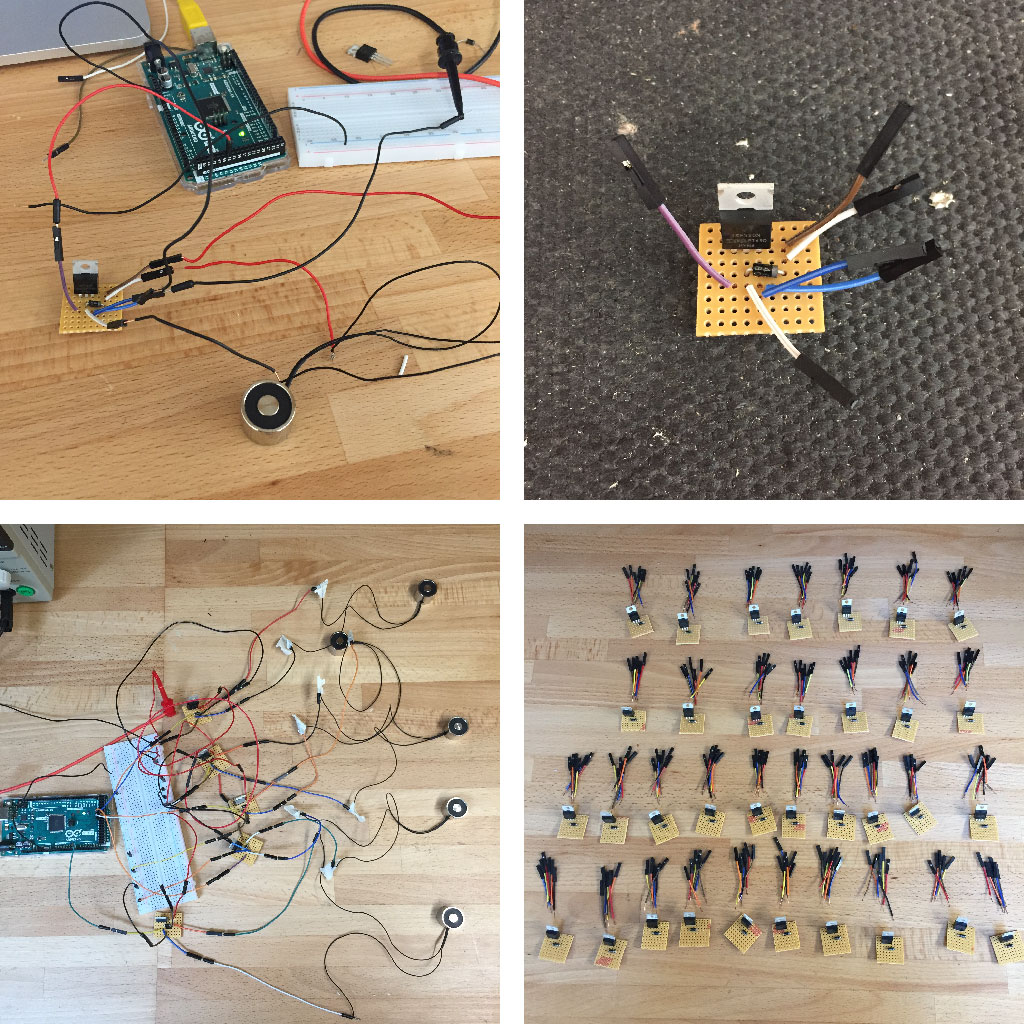

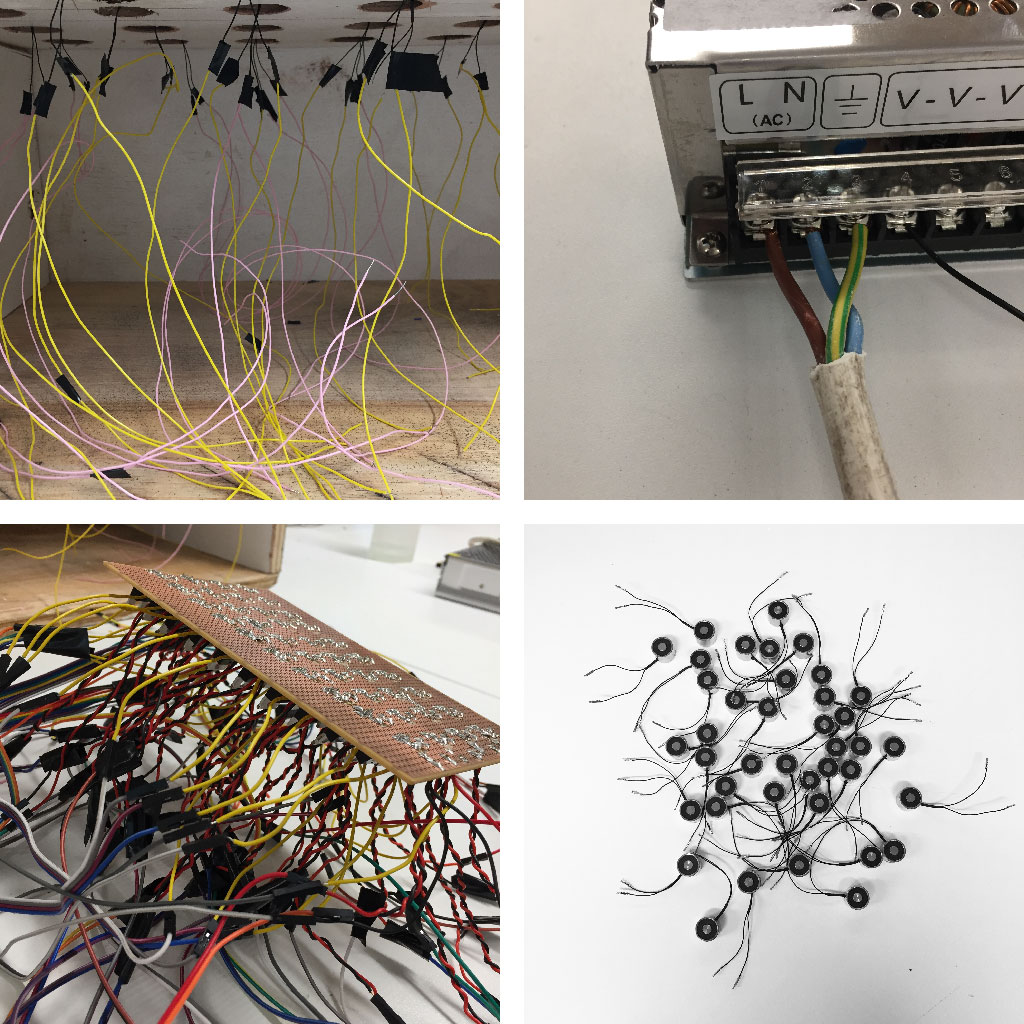

At the heart of the piece is an openFrameworks app controlling both an output image and an array of electromagnets via an Arduino. The basic setup builds on the app used in Prima Materia, using the firmata to control the arduino, and ofxMaxim as the basis of the timekeeping system for controlling the pulse patterns of the magnets [5].

I chose to arrange the output as a vertical stack of three videos, leaving it in a nonstandard aspect ratio. This meant building a custom projection screen out of wood and white silk, and then using ofxPiMapper [7] within the app to make sure the image could be mapped to the correct size.

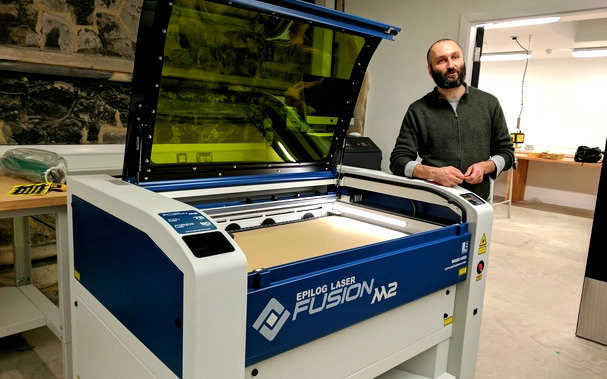

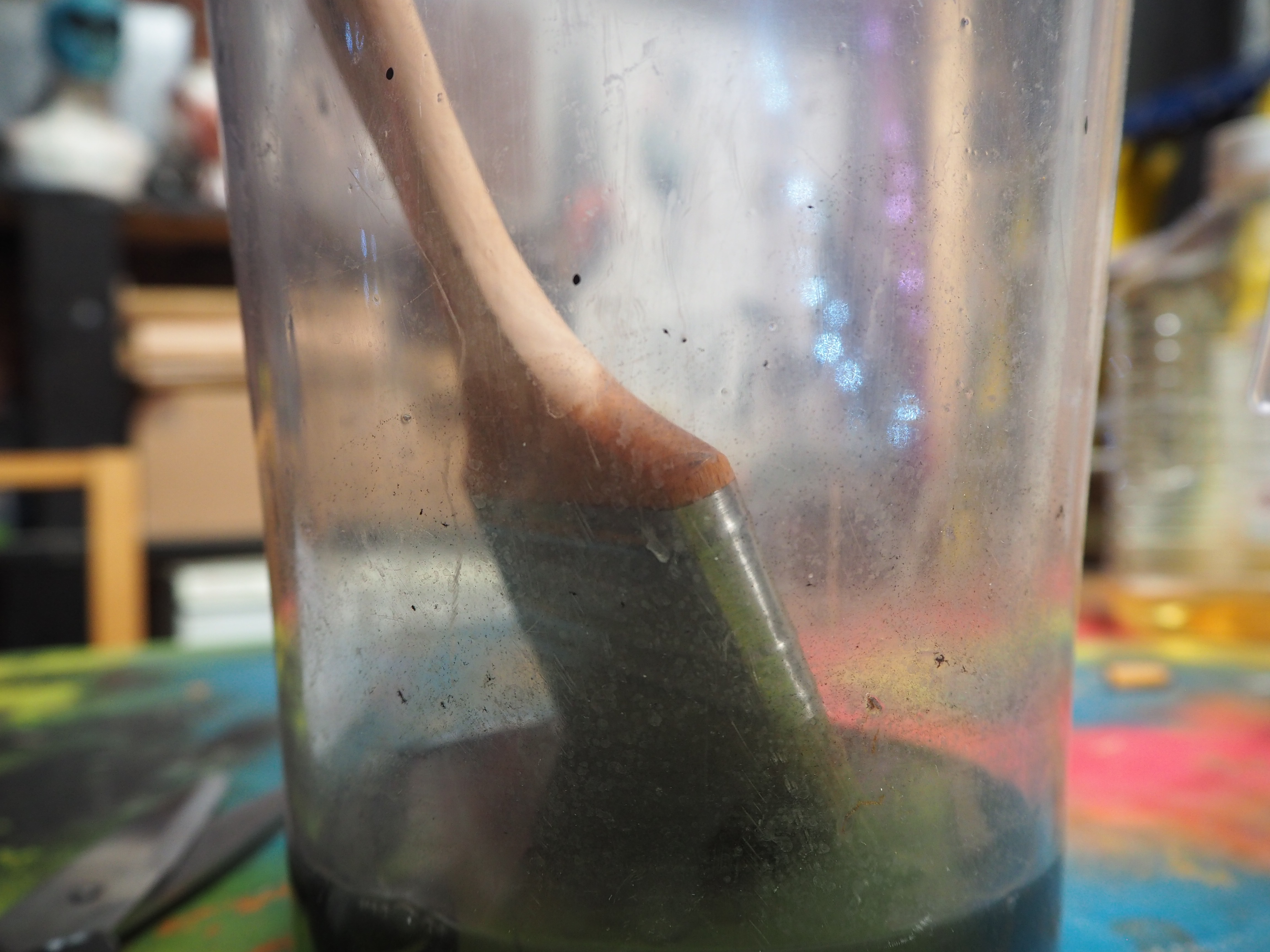

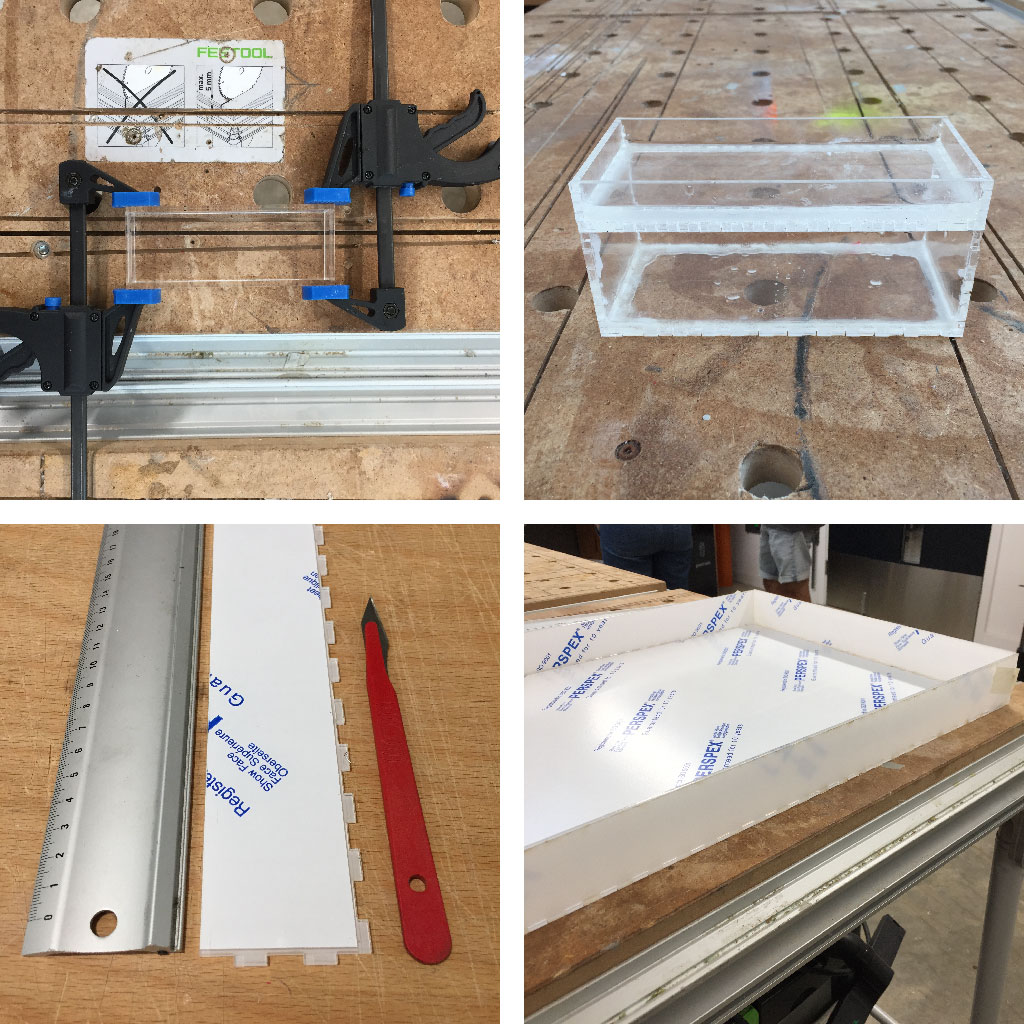

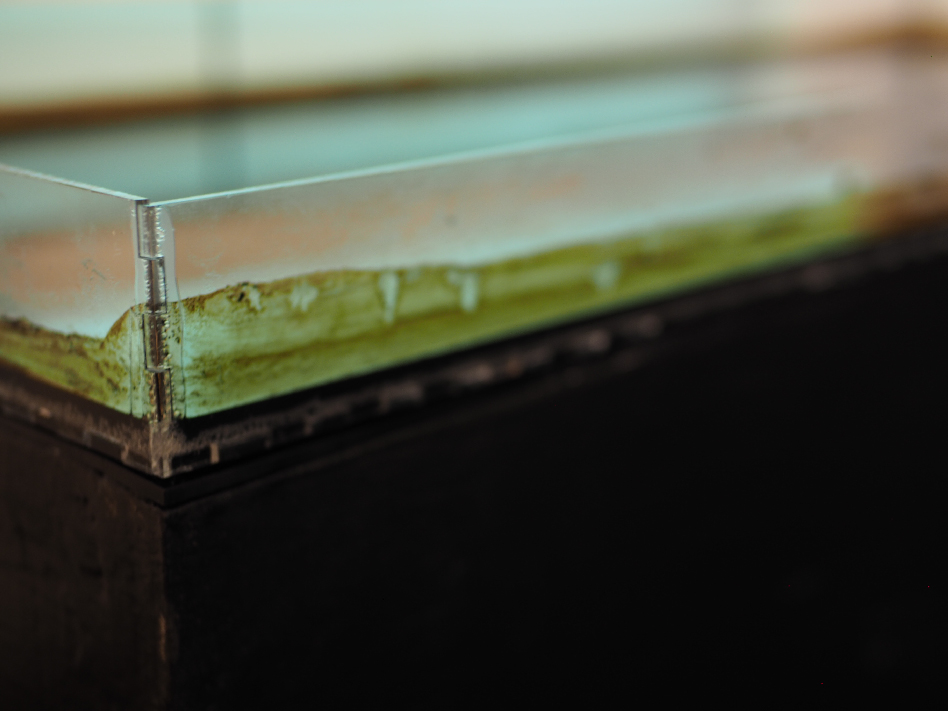

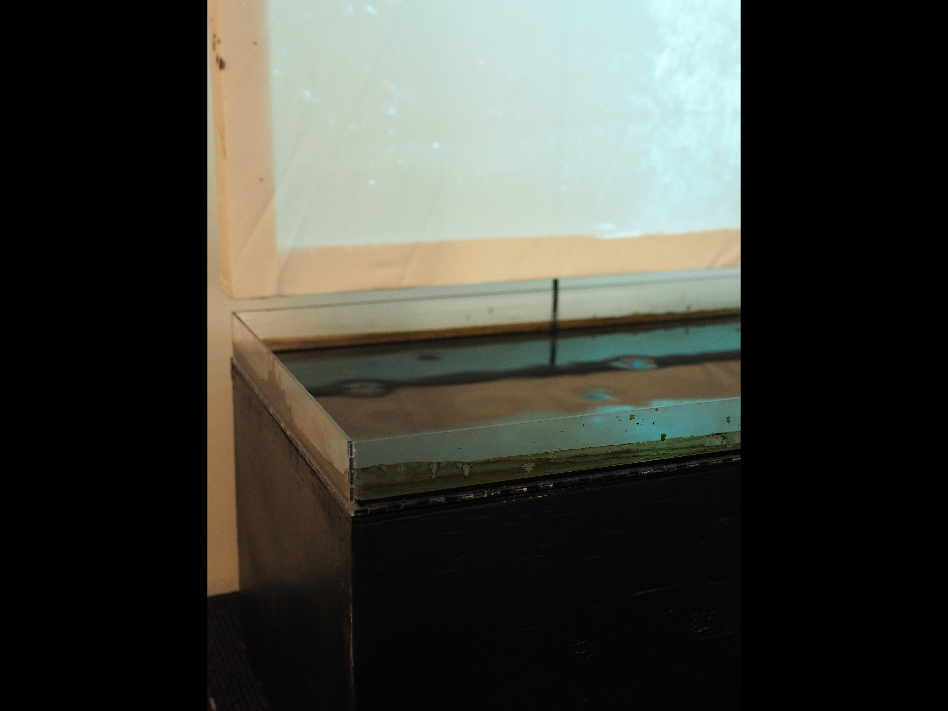

The biggest technical challenges in the project came from building and obtaining its physical components. These consisted of a perspex tray to house the ferrofluid, a wooden box housing the computer and circuitry, an array of forty electromagnets, and the ferrofluid itself. I wanted to make the tray as big as possible, to maximise the amount of visible ferrofluid. My restrictions were the size of the laser cutter and the high cost of ferrofluid. I settled on a 1000mm x 400mm x 50mm tray. This turned out to be ambitious, and I spend a huge amount of energy learning how to engineer a watertight perspex tray strong enough to hold a litre of oil, and experimenting with different ways of making ferrofluid at home.

After several experiments with the tray I was able to make one which worked, using jagged edges to join the faces and judicious application of Bostik to seal the inside. I was initially concerned the jagged edges would not look precise enough, but as the aesthetic of the project progressed a slightly rougher look felt acceptable. I had initially planned to have a second perspex box beneath the tray which would both raise it, placing visual emphasis on it, and expose the wiring underneath. Ultimately this proved too difficult to make and too expensive to buy, so I settled with placing the tray directly on the wooden box housing the computer. As the piece developed conceptually this seemed to make more sense, as I wanted to draw attention to the motion on the fluid rather than the mechanism causing it.

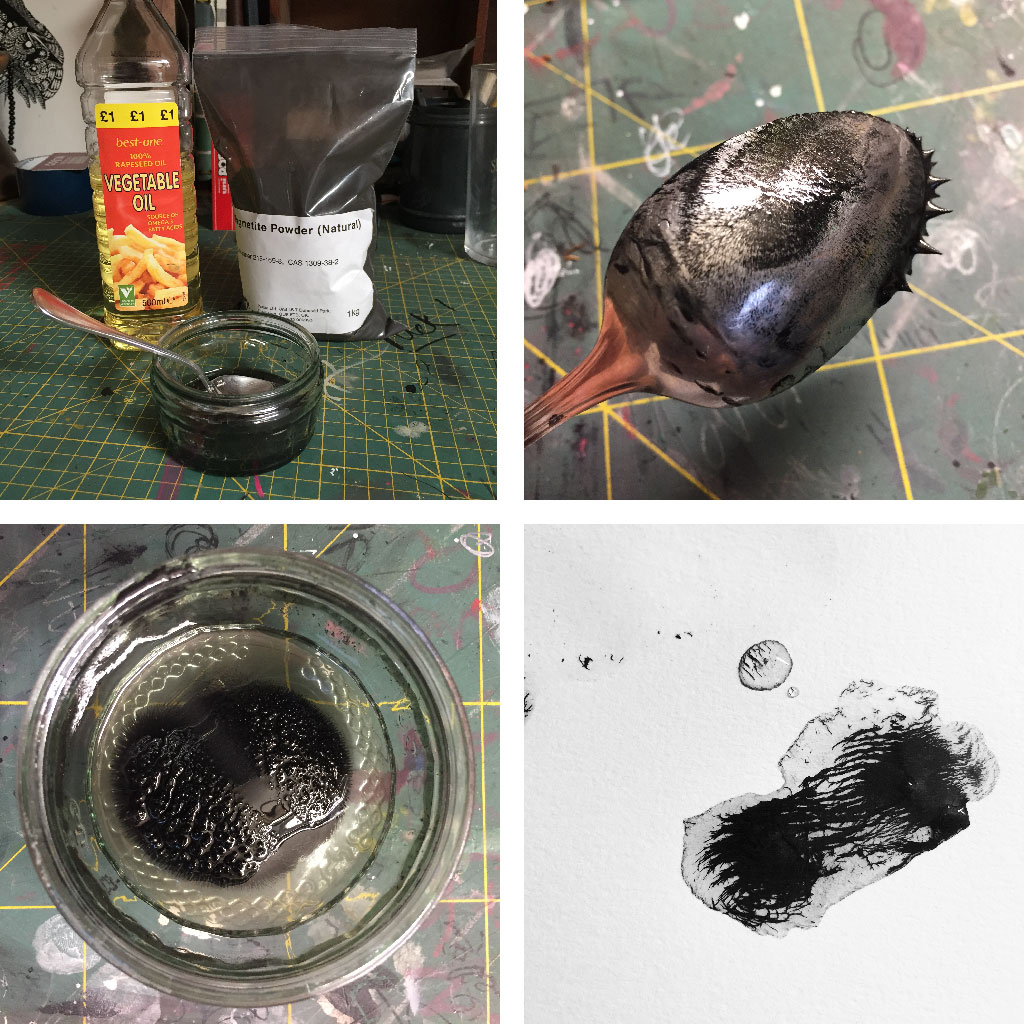

In total I needed 1 litre of ferrofluid. I tried various recipes for homemade ferrofluid that I found online [8]. The first was to strip iron oxide from old VHS tapes using acetone. This proved to be far too labour intensive to be viable. The second was more promising: buy magnetite (iron II, III oxide) and then mix it with vegetable oil. I had some success with this method. It yielded a black(ish) reflective liquid which moved in the presence of a neodymium magnet. Since the layer of fluid in the tray was only going to be one or two millimetres I wasn’t too concerned about separation. (In commercial ferrofluid the iron oxide particles are coated with a surfactant, usually oleic acid, which stops them from clumping and sinking. I looked into the chemistry involved in creating this at home but it was too complex given the time I had available.) However when it came to testing it with the real installation setup it did not work. The electromagnets were just not strong enough. So I had to reluctantly and hastily buy some real ferrofluid at the last minute. Its colour (a much deeper black) and lower viscosity made it far better for the piece than my homemade efforts. But not all was in vain: many of the experiments and materials involved in my failed alchemy of ferrofluid found their way into the final piece via the footage.

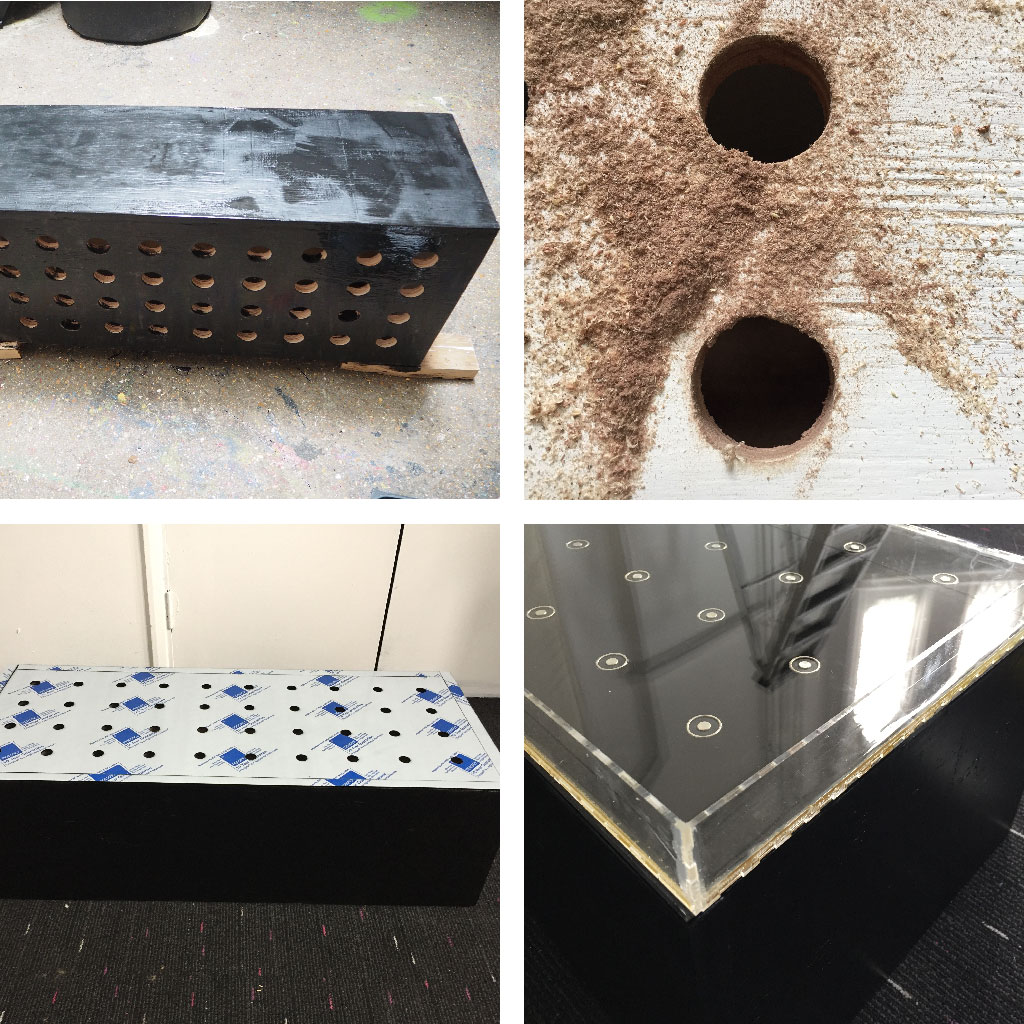

The box housing the technology was built out of wood reclaimed from around Hackney Wick and spray painted black. I was expecting the circuit to be straightforward, as it was in essence a bigger version of circuits I’ve made for various projects earlier in the year. But the increase in scale actually represented a huge amount of work in itself, and it took several attempts to design and implement the circuit in a way which did not leave it extremely fragile. In my first attempt I tried to keep it modular. But this ended up involving an untenable amount of wiring. So I soldered everything into a single board, which reduced the wires significantly and ultimately made it possible to make the circuit robust.

Future development

As a future direction for this project I’d like to place more emphasis on the ferrofluid itself, rather than the images behind it. The dark room in which it installed and the relative size and placement of projected image and ferrofluid drew the viewer’s attention to the projected image first. One way to achieve this would be to work with a larger pool of fluid, so that the entire reflection is visible at the same time, creating a sense of true doubling. Another way might be to raise the pool (as had been my initial intention). Scaling down the image itself is also a possibility, though I believe for this to have the intended effect it needs to be large.

Self evaluation

One of the major difficulties in this project was that despite doing some initial testing, it was very difficult to get a sense of how it would work until it was built at full scale, by which point I would be committed to it. This point in mind, I was extremely pleased with way it turned out aesthetically. I felt the reflection of the image highlighted the ferrofluid motion as I envisaged, and the design and footage created the sense of meditative calm I was aiming for.

The conceptual development of this piece felt like it happened faster than was natural, due mainly to the time constraints of the course, and I believe this can be felt to some extent in the final outcome. With more time to work on it I believe I could refine the conceptual content of the piece and communicate it in a more focused way.

Technically the piece turned out to be quite a struggle, and I am extremely pleased that it all ended up working as it was intended to. This was partly due to my underestimation of the cost of upscaling—a valuable lesson to learn. Another factor was that I deliberate chose a project which would lean on skills I am less familiar with (fabrication, electronics, cinematography, woodwork), and downplay ones I am familiar with (programming). Perhaps it would have been wiser to chose a more code-oriented project, but since my goals were to learn new skills as much as to make a great artwork, I am happy with how it has turned out.

References

- Interagency, Samuel Ludford

- Prima Materia, Samuel Ludford

- Alejandro Jodorowsky & Marianne Costa, The Way of Tarot: The Spiritual Teacher in the Cards

- Steven Shaviro, Three Essays on Accelerationism

- Prima Materia technical documentation

- Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins

- ofxPiMapper

- How to make ferrofluid at home