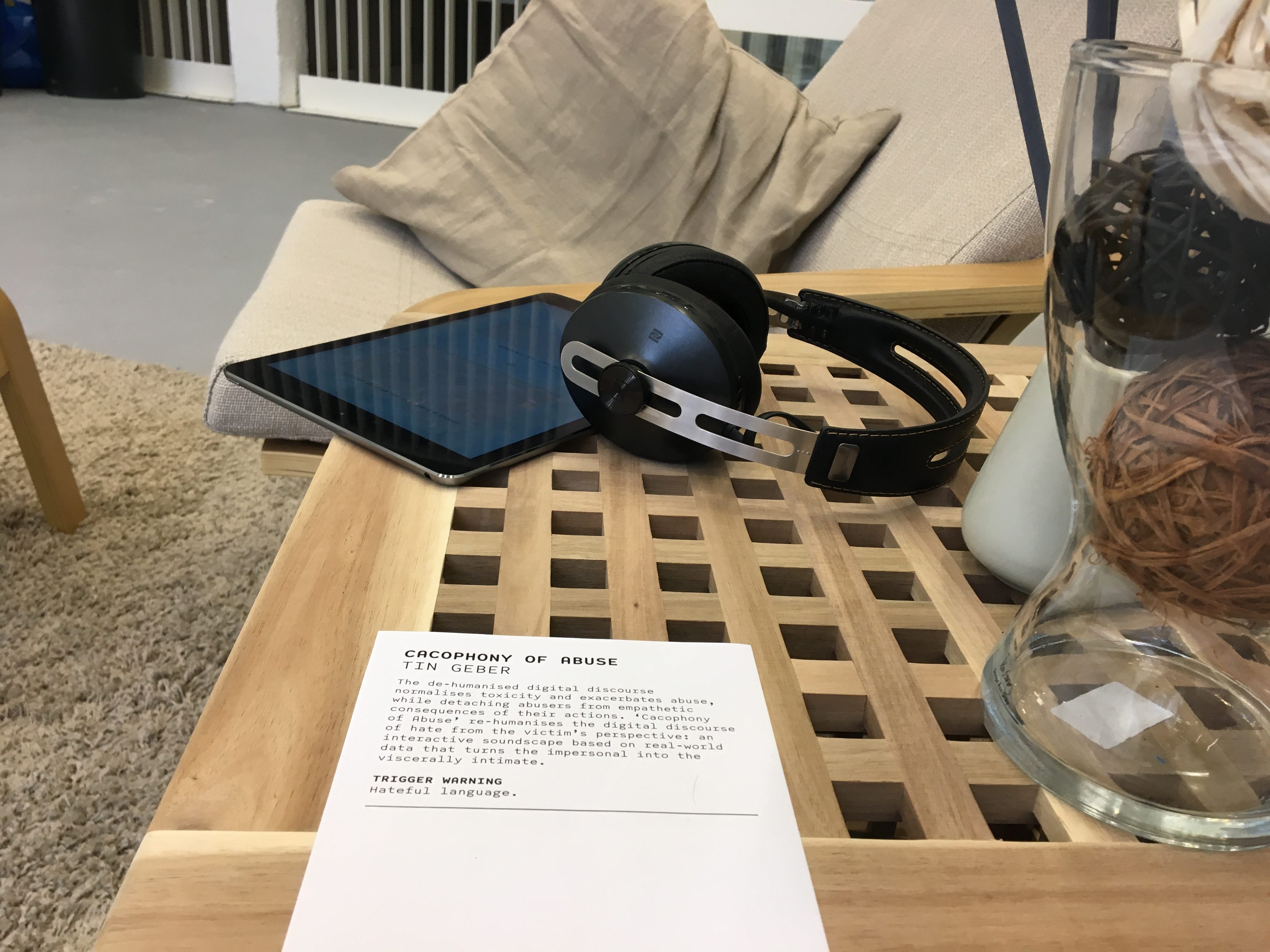

Cacophony of Abuse

The de-humanised digital discourse normalises toxicity and exacerbates abuse, while detaching abusers from empathetic consequences of their actions. Cacophony of Abuse re-humanises the digital discourse of hate from the victim's perspective: an interactive soundscape based on real-world data that turns the impersonal into the viscerally intimate.

produced by: Tin Geber

Introduction

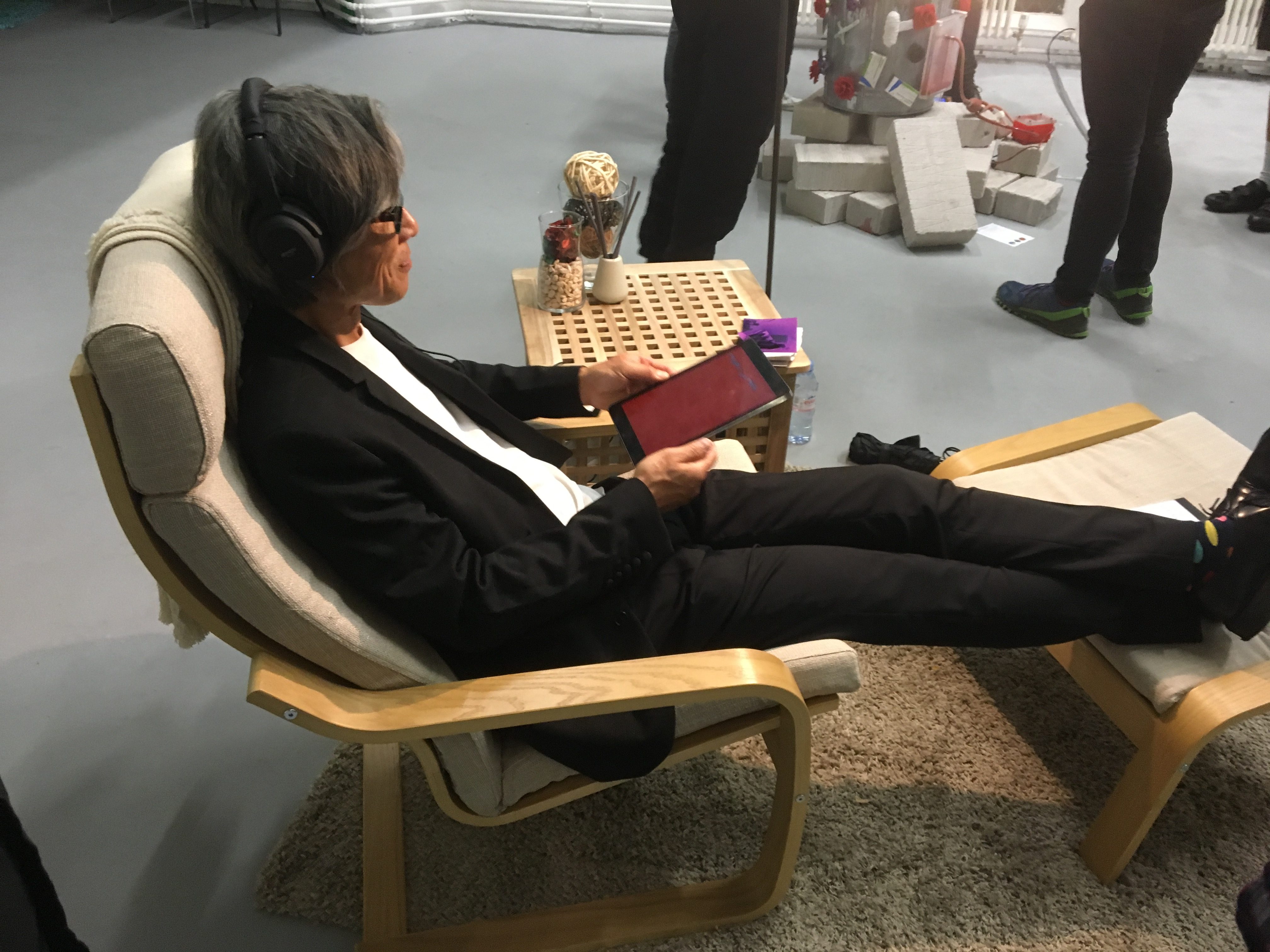

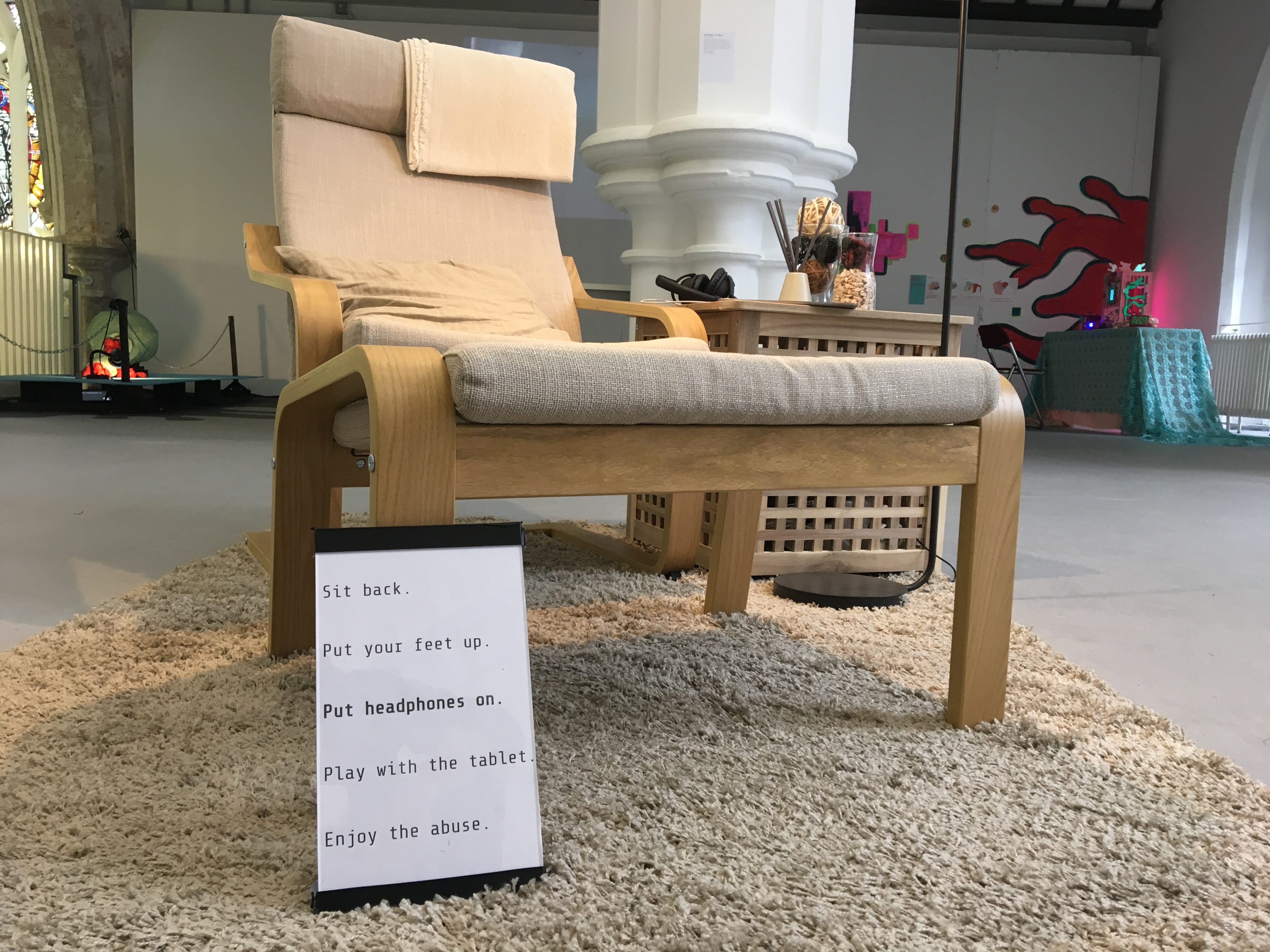

You’re invited to sit back and relax, and broadcast your thoughts on a tablet, as you would normally do when engaging with social media in your living room. Any digital interaction opens us up to online toxicity— when engaging with Cacophony of Abuse, this toxicity is represented with sound, in a crescendo of hateful replies, enclosing and surrounding you.

Cacophony of Abuse is an uncomfortable experience, and it gets worse as it progresses. There are multiple ways to interrupt the experience; however, they all represent a compromise and a reduction of agency.

Concept and background research

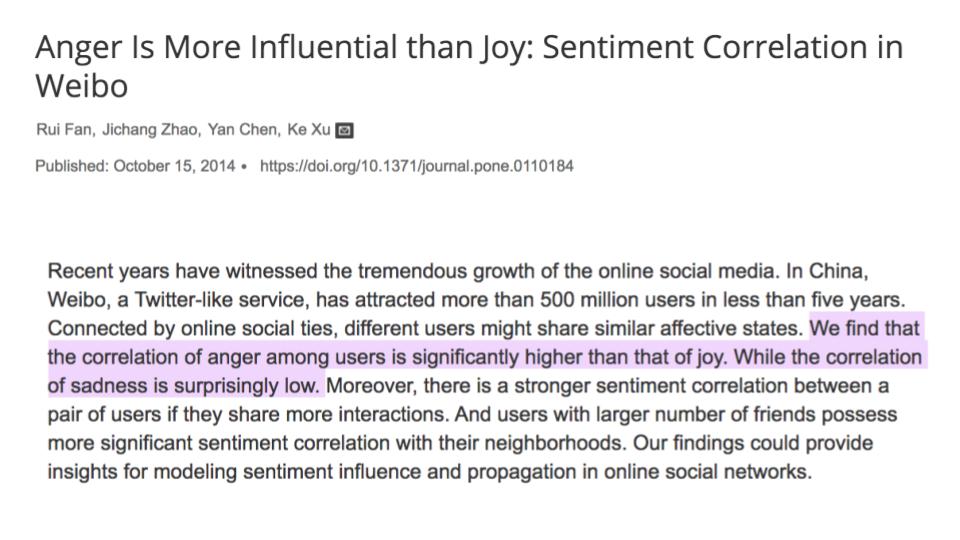

At the heart of this project is an exploration of the emotional effects of mediated human interaction. I wanted to recreate a personal echo-chamber of emotional response, seen through the lens of online discourse. Initially, my desire was to modify the audience’s perception of their beliefs when supercharged through the social media amplifier — from good to amazing, from bad to horrible. However, early in my research I understood that, when analysing the strength of online response to events, anger is much more influential than joy (Fan et al. 2014). That is when I decided to focus on the emotional effects of online abuse: how does broadcasting on social media distort, darken, and destabilise a person?

Cacophony uses sound instead of text for its expression of abuse. Text is cognitively parsed and therefore has a higher level of abstraction, which makes it harder to immediately recognize the extent of abuse or its long term effects. Sound, on the other hand, travels down a priority lane into our primeval and visceral instincts: it triggers emotional responses before we have the time to cognitively parse it for meaning and sanitise its effects (Ghuntla et al. 2014; Seltzer et al. 2012).

The data

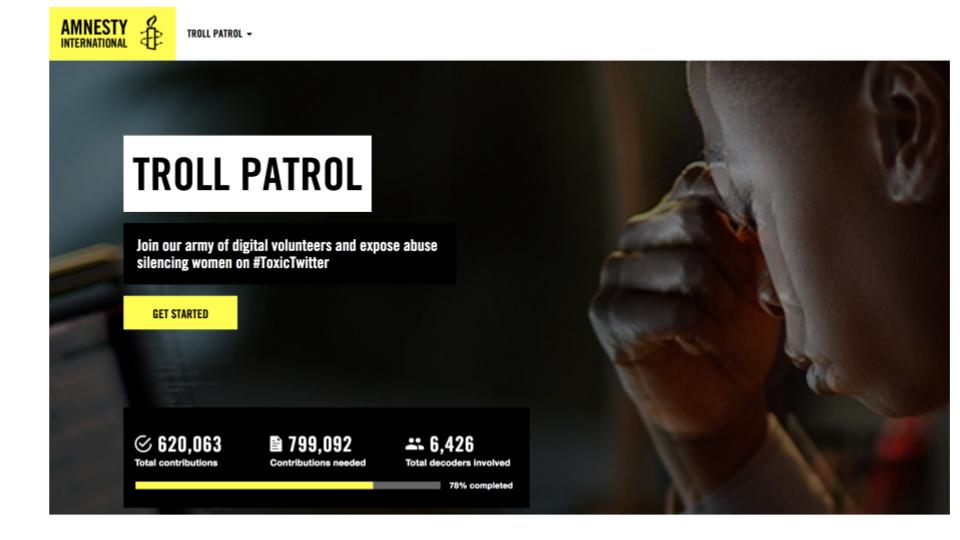

In order to make the project realistic and plausible, I based the list of abuses on Amnesty International’s Troll Patrol project (Amnesty International n.d.). Troll Patrol crowdsourced flagging of abusive content on Twitter, especially towards women. With support from the Amnesty team, I collected a list of abusive statements that were most representative of the type of abuse most frequently encountered on Twitter. This list was highly offensive towards targeted groups: I cleaned the language enough so that the abuse isn’t clearly directed towards specific groups, but can be felt and internalised by a wide range of (English-speaking) audience members.

The end result was a list of 55 representative expressions of abuse. I tagged each based on whether they are targeting a person’s right to have an opinion, right to speak, or right to express, own, or support an identity. Lastly, there were two domains of statements of pure abuse (either individual or generic).

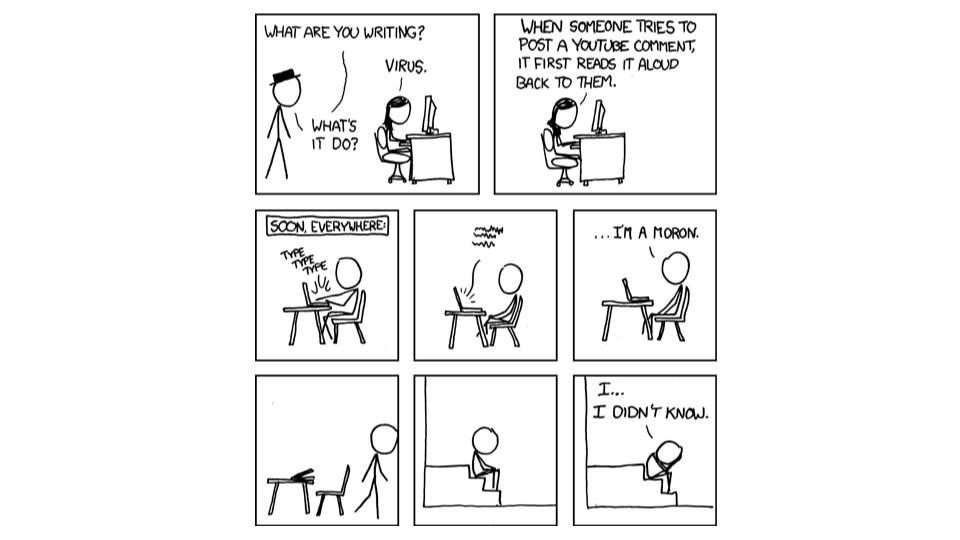

The ultimate goal of Cacophony is to create empathetic links between expressions of online abuse and the audience: it isn’t intended for the victims of abuse, but rather for potential (current or future) abusers. By creating a visceral connection between expressing a belief and the toxic effects of abusive responses, audience members are left with a lasting feeling of deep discomfort: a feeling that they might remember once they’re about to take the role of the abuser when engaging in online discourse (Munroe n.d.).

Technical details

Cacophony of Abuse is composed of a server running SuperCollider (SuperCollider n.d.) for the sound experience, and a tablet app made with OpenFrameworks (“openFrameworks” n.d.) for the interaction. The app triggers different audio patterns via OSC (“Opensoundcontrol.org | an Enabling Encoding for Media Applications” n.d.) when the audience interacts with it. I used "ofxDelaunay" and "ofxOsc" Open Frameworks addons.

Sound experience

I had 12 people record these statements, together with a variety of vocalizations and reactions, for a total of 3400 separate sound bites. I then cleaned and tagged each based on intensity, type of voice, and the abovementioned dimensions of abuse.

This archive of sound files is played back by SuperCollider, triggering files in complex tag-based semi-random binaural patterns: this means that, if you’re experiencing Cacophony of Abuse, you will hear an ever-changing crescendo of targeted abuse, that will feel like it’s coming from anywhere in the space around you - even right behind you.

SuperCollider patterns and synths are triggered via OSC by the iPad app.

Interaction

The iPad app shows both a carousel of pre-defined statements, as well as letting audience members to enter their own statements. While in the “choosing” state, the headphones play a soundscape of random chatter, to evoke a space where multiple people are interacting.

Once the audience member chooses a statement, the chatter dies down and they are exposed to a crescendo of abuse. The abuse keeps growing, and the text on the screen begins to unravel, slowly losing its meaning as the abuse intensifies.

There are three obvious ways to stop the experience:

- Taking off headphones and walking away;

- Waiting until an “ESCAPE” button appears;

- Waiting much much longer until the abuse stops by itself.

There is also a fourth, less obvious way to stop the abuse.

Physical environment

Cacophony requires a comfortable yet neutral and sterile setting. The current iteration recreates an IKEA living room experience, that is inviting and relaxing enough for the audience to subconsciously position the experience in a comfortable, known environment (or as one audience member said, “as soon as I sat down, I felt like I was in my living room.”) The color palette is purposefully narrow (beige and light oak), and all the physical components are dead (no plants, for example.)

The physical part of Cacophony is relatively easy to install, as long as the exhibition space can ensure a comfortable and neutral living-room-like setup:

- Lounge chair with foot stool

- Light source - a floor lamp

- Table

- Rug that defines the area for the experience: all the components need to fit on it

- Accent objects and decoration: a pillow, a blanket, decorative objects for the table (incense sticks, glass containers filled with rocks)

- Power source (preferably hidden within/under the table)

- Reliable wifi

- Noise-cancelling over-ear headphones

- Current tech requirement: iPad, computer (any OS)

- Future tech requirement: just a tablet (any OS)

Future development

In order to simplify installing of Cacophony in galleries and exhibition spaces, I plan to combine the sound and interaction into a single cross-platform app, by porting the code to Unity. Currently the technical components require an Apple tablet, and a separate computer running the sound experience, which requires technical expertise when installing.

Self evaluation

Evaluating an experience designed to be hated is complex. I received feedback from many people who experienced Cacophony and were visibly shaken by it. They were both conceptually grateful and emotionally disturbed. I didn’t expect to be so ambivalent about the success of Cacophony — and at the same time, I wasn’t prepared for the secondary trauma I would feel caused by recording and editing thousands of audio files of abuse. Overall, I feel pretty much the same as the people who experienced Cacophony: shaken, but grateful for the experience.

Since this was the final project of my Masters course, I decided to technically challenge myself, and work in two areas I haven’t before: computational audio, and app development. Due to my lack of expertise, the best solution was also a less elegant one: two separate devices, one for interaction and one for sound. For the audience it didn’t make a difference and arguably, the realisation that closing the app doesn’t make the abuse stop might have been worth it. For the future, my next challenge will be to combine the two in a single, elegant app.

References

Amnesty International. n.d. “Troll Patrol - Amnesty Decoders.” Amnesty International. Accessed September 12, 2018. https://decoders.amnesty.org/projects/troll-patrol.

Fan, Rui, Jichang Zhao, Yan Chen, and Ke Xu. 2014. “Anger Is More Influential than Joy: Sentiment Correlation in Weibo.” PloS One 9 (10): e110184.

Ghuntla, Tejas P., Hemant B. Mehta, Pradnya A. Gokhale, and Chinmay J. Shah. 2014. “A Comparison and Importance of Auditory and Visual Reaction Time in Basketball Players.” Saudi Journal of Sports Medicine 14 (1): 35.

Munroe, Randall. n.d. “Xkcd: Listen to Yourself.” Accessed September 12, 2018. https://xkcd.com/481/.

“openFrameworks.” n.d. Accessed September 12, 2018. https://openframeworks.cc/.

“Opensoundcontrol.org | an Enabling Encoding for Media Applications.” n.d. Accessed September 12, 2018. http://opensoundcontrol.org/.

Seltzer, Leslie J., Ashley R. Prososki, Toni E. Ziegler, and Seth D. Pollak. 2012. “Instant Messages vs. Speech: Hormones and Why We Still Need to Hear Each Other.” Evolution and Human Behavior: Official Journal of the Human Behavior and Evolution Society 33 (1): 42–45.

SuperCollider. n.d. “SuperCollider » SuperCollider.” Accessed September 12, 2018. https://supercollider.github.io/