Unravelling External Authorities with Nonhuman Witnessing

I decided to explore the theories of cognitive dissonance and self-perception, encountered during the first term’s group project on the sense of touch. After going over the main cognitive processes behind the making of values and attitudes, I tried to update Daryl Bem’s example with feminist STS. Finally, I speculate on the potential effects of analyzing personal datasets (gathered by digital assistants and social medias) with machine learning on self-perception. Can ML make us aware of previously nonconscious cognitive phenomenons? I produced a short animated video generated with neural networks to illustrate the ideas of external authorities, doubt, values and memories.

produced by: Julien Mercier

final artefact-video, WHY DO I NEVER DO ANYTHING I TRULY BELIEVE IN? (youtube link)

Typographic disclaimer:

[edit: I unfortunately didn’t find the way to achieve it on the webpage, it is only present in the pdf version.] Quantum theory has informed research in all fields for decades. I am obsessed with the matters surrounding the uncertainty principle and how “doubt” has become a worthy mathematical figure. I hypothesize that this new value assigned to doubt has yet to implant our cognitive experience of the world. It is not unreasonable to think that we will learn to function with doubt, and that it will slowly become part of our innate cognitive tool set, by some sort of epigenetic process. In order to graphically express this notion, and because I find the mono-lined flow of written expression too limiting at times, I have devised a little typographic tool that I use throughout this essay to express the superposed “quantum” state of a notion, when its exact value cannot be determined. As urged by Maturana & Varela, (MATURANA & VARELA, 1987) we should “refrain from the habit of falling into the temptation of certainty.”

Introduction

1. The cognitive making of belief systems

2. Stereotypes as underfitted models

3. Cognitive dissonance and attitude change

4. Lie detectors and the contagion of attitudes

5. Self-perception: attitudes follow behaviours

6. From consistency to ideology

7. Unravelling external authorities with nonhuman witnessing

Annotated Bibliography

Additional references

Introduction

If you believe in “seeing first,” you’re welcome to watch the above video that resulted from the research.

I first came across the notion of cognitive dissonance (FESTINGER, 1957) while doing research on neuroscience and the sense of touch, during the first term’s group project. Its premise is as follows: dissonance is psychologically uncomfortable and motivates a person to try to reduce the dissonance to achieve consonance. It is one of the early theories that opposed the prevailing behaviourist theories of the time, by explaining phenomenons that the mere observation of external manifestations couldn’t. It seemed to put in words sensations that I had experienced in the past. I had the uninformed hypothesis that opinion-making is highly environmental, temporal, and changeable. I had the intuition it could inform the distance between actions and beliefs. I wanted to research the surrounding existing theories and compare them to my own experience, in order to derive explanations for larger phenomenons.

I was interested by the question: “How are the systemic prejudices of our society maintained?” The introspective counterpart to this question was that of my own situation: “To what extent do the values that are important to me have an impact on my attitudes?” I started by looking at the theory of self-perception, (BEM, 1967) which is presented as an alternative to Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance. Recursively, and because the idea of self-perception suggested it, I tried to use some of my own experiences as a subject of inquiry. As a result of my attempt to “update” some of Bem’s examples with feminist STS perspective, I used some of Sandra Bem’s theory. I also tried to inform Bem’s central notion of “external authority” with examples from Adrienne Rich, Teresa de Lauretis, Michel Foucault, Evelyn Fox Keller, and Hannah Arendt.

Finally, I also wanted to look speculate on the impact of technology on the cognitive foundations of values. I created an artwork informed by these researches. At first, I thought that only my practice would benefit from encountering those theories. But I now think that computational practices can inform them in return. As we’ll see in the essay, this type of reciprocal structures also exist between attitudes and values, in the continuity of the fluid, networked relationships that material semiotics describe. One of the ulterior motives behind researching self-perception is to imagine computational ways to transcend the limit that it is. Thus, this essay ends with a speculative proposal that lays the grounds for a computational strategy to visualize, deconstruct and become aware of the external authorities at play in the making of belief systems.

Visual researches for the final video. While trying to come up with neural networks-generated representations of external authorities and the effect they might have on me, self-perception theory informed me that reciprocally, it should also represent the effect that I have on others. Luckily, the structure of the data-training-and-testing flow is particularly fit for such interconnections. Source material is taken from my own past and trained with conditional neural networks. These memories represent the external authorities as technologies of sex described by de Lauretis and Foucault, and ideological state apparatuses as described by Althusser. The full technical development was made as part of the Machine Learning course and is visible at this url: pix2pix.julienmercier.in

1. The cognitive making of belief systems

A belief is like an equation. It binds together two objects, or one object and a characteristic of it. Collectively, a set of beliefs compose an individual’s understanding of themselves and their environment.

The notion of primitive beliefs in the context of belief systems appears in Milton Rokeach’s attempt (rOKEACH, 1973) to predict behaviours such as political or religious belief by ranking a person’s “terminal values.” [1] Daryl Bem (BEM, 1970) extends on the notion and categorizes them as follow: zero-order, first-order, and high-order primitive beliefs.

Zero-order beliefs are a type of primitive belief whose strength makes us virtually unaware that an alternative may even exist. We are not aware of their presence until they seem to be violated. Object permanence is an example of such belief: even when they are out of my sight, I expect objects to continue to exist. A magic trick that “make things disappear” may infringe on my belief in object permanence and temporarily put me in a state of cognitive dissonance. These concepts are learnt from an early age, and are continuously confirmed by experience. The use of virtual reality headsets in young children presents the risk of disrupting the normal development of such concepts. (HILL, 2016) A brain in a state of cognitive dissonance shows very distinct signs through RMI. A psychiatrist explained me how he uses VR to induce a state of cognitive dissonance and reveal cognitive disorders: the VR set displays an object touching the subject’s shoulder, while a robotic arm actually touches their shoulder, with a minor time lag. The time (in milliseconds) their brain takes to restore the consistency of the situation is measured. A slow result might indicate risks of various cognitive disorders. The zero-order belief we have in our senses is the most important of our cognitive system. Nearly all of our other beliefs rest upon it. Problematically, Bem explains that some religious beliefs beliefs similarly support many other beliefs, making them extremely hard to overcome, or even question.

First-order beliefs describe beliefs that are inferential, yet for which alternatives can easily be conceived. The following syllogism is an example:

premise #1: My senses tell me that apples are round.

premise #2: My senses tell me the truth. [<- this is a zero-order belief]

= conclusion: Therefore, apples are round. [<- this is a first-order belief]

Psychologically, the first premise is equal to the conclusion. The inferential relationship the conclusion has with a zero-order belief is nonconscious. I am generally aware of my first-order beliefs, and I can consider alternatives. Although I have never seen one, I do not cognitively exclude the possibility that a square apple may exist. (especially in our age of genetic engineering)

High-order beliefs are those of our primitive beliefs who are not based on our own experience of the world, but on that of an external authority, Bem explains. Their origin is differenciated. The existence of a black hole in the center of our galaxy, religious tales, the fact that a branded perfume will facilitate the search for a sexual partner… They all can be “pushed back” until they are seen to rest ultimately upon a basic belief in the credibility of someone else’s experience. Cognitively, the external authority’s experience is as “valid” as a direct one. All of the “evidence” used to justifiy a high-order belief needs not be remembered. It doesn’t matter if I forget how I got convinced that there is a black hole in the center of our galaxy, I will still believe in it after I forgot the chain of justifications. As we become older, we learn how to consider high-order beliefs with more distance, regard them as fallible, and we grow more wary of external authorities. Our beliefs are constantly being rebuilt, based on chains of first-order beliefs, forming higher-order beliefs. The first premise and the conclusion are no longer synonymous. An example of a high-order belief system could be:

premise #1 My doctor says that smoking causes cancer.

premise #2 My doctor is part of the scientific community.

premise #3 The scientific community’s methodology is more reliable than my own conclusion on the matter.

premise #4 However, the scientific community has been used to justify eugenics in the past.

premise #5 I’d rather not have cancer.

premise #6 My uncle smoked and he died of cancer.

premise #7 There are thousands ways to die.

premise #8 Some of my idols smoke.

premise #9 Smoking is the most enjoyable part of the day at work.

premise #10 Buying stop smoking treatments will make me quit smoking.

premise #11 Over time, smoking is more expensive than treatments.

premise #12 Companies who sell cigarettes are unethical.

premise #13 This politician who sits in the European Parliament is a trustee in a tobacco company.

premise #14 Many sitting European politicians are in bed with oil, tobacco, drugs, pesticides, or weapon companies.

premise #15 The European Parliament is corrupt. = conclusion Vote leave!

High-order beliefs are more likely to be discredited, as any of the many links they entertain with other belief systems could be contested, causing its vertical structure to wobble. But beliefs are also organized horizontally: other chains may reach to similar conclusions. Thus, even if a vertical structure is weakened, such intricated structure will allow it to resist. Over time, the broad horizontal chain and the deep vertical ones reconfigure without causing the final belief to change.

[1] Rokeach’s terminal values are: True Friendship; Mature Love; Self-Respect; Happiness; Inner Harmony; Equality; Freedom; Pleasure; Social Recognition; Wisdom; Salvation; Family Security; National Security; A Sense of Accomplishment; A World of Beauty; A World at Peace; A Comfortable Life; An Exciting Life.

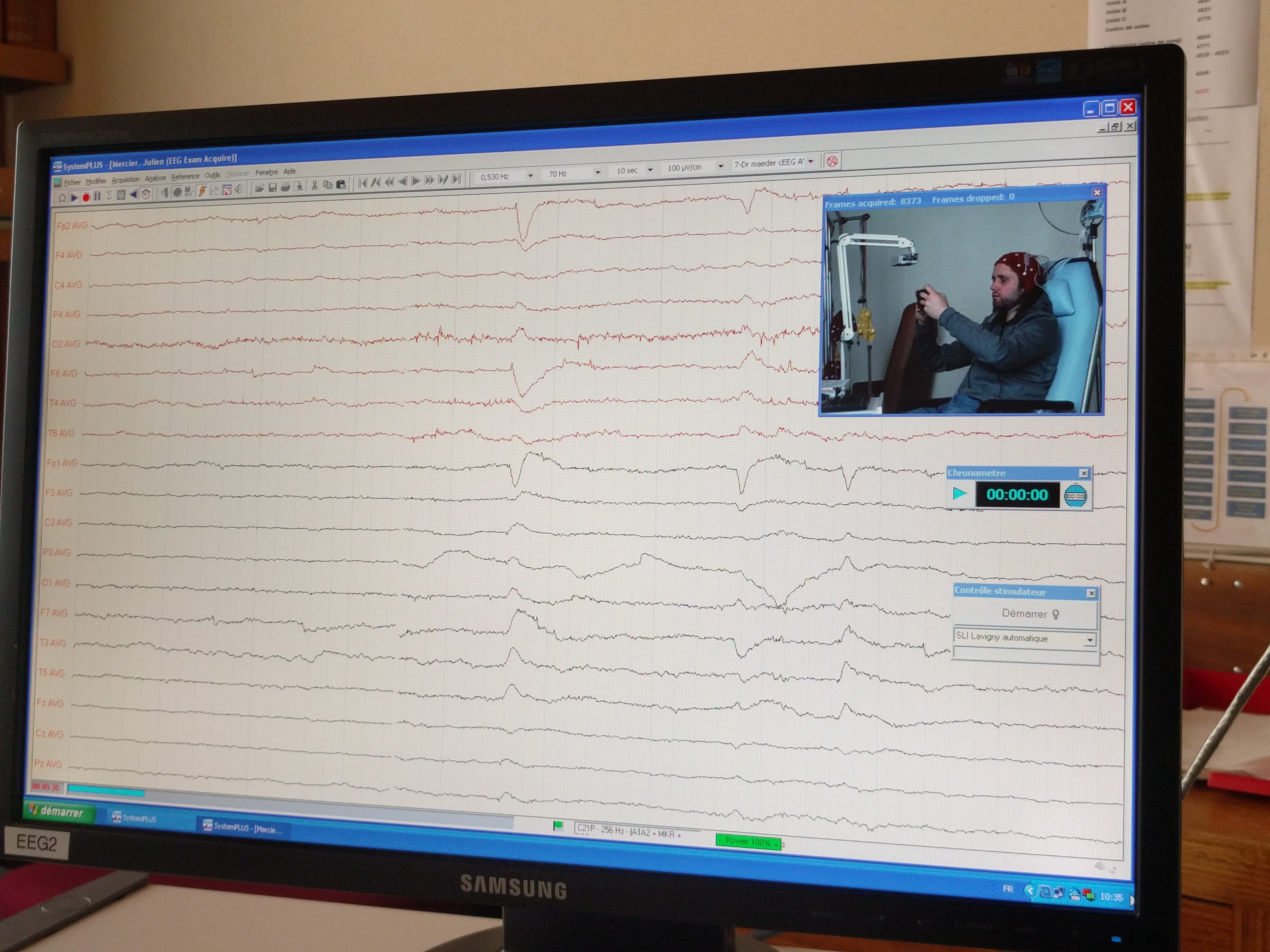

Early in my research, I attempted to use EEGs to witness signs of cognitive dissonance, and compare various situations I would have put myself in. Unfortunately, the data was too noisy and this kind of signals are extremely hard to see, even for trained professionals. This screenshot is from an EEG session I passed on the 9th of April at a local hospital in Switzerland.

2. Stereotypes as unfitted model

Primitive beliefs are not flaws, nor excessive naivety, but an epistemological and psychological necessity. They usually don’t result from a single experience, but from the generalization of many sources. In Discipline and Punish (FOUCAULT, 1975), Michel Foucault describes the way ancient penal systems relied on fragments of evidence pieced together: A visual witness was worth a “half evidence,” oral testimony was worth a “quarter of evidence…” Even hearsay was worth an “eighth of evidence.” With pieces of each added together, it wasn’t difficult to reach “full” evidence for inquisitors. I would argue there are similarities with the way our belief systems are built: While we may feel like our beliefs rely mostly on “quality” low-order witnessing, we place unequivocal faith in external authorities at an alarming frequency. In turn, these external authorities place their faith in even more differenciated sources. In such a configuration, a belief may never need any material evidence whatsoever to fully materialize. It suffices for a source to become regarded as an external authority. Of the many ways this could be achieved, only a minority include logical and fair reasoning.

When we consider generalizations as universally true, they become stereotypes. They are overgeneralized beliefs based on limited experiences. Stereotypes are necessary cognitive thinking devices who help us simplifying experiences into a manageable amount of information. In machine learning, a model is said to be “overfitting” when the results it produces correspond too closely to a particular set of data, and thus may fail to predict future observations reliably. In some cases, an overfitted model may be desirable. in turn, this analogy examplifies a widespread stereotype itself: the common misconception is to regard the computer as amazingly similar to the human. Evidently, human preceded the computer, and it is the computer that bears resemblances to mankind. This mutual relationship is of the type described by material semiotics: as our understanding of human cognition deepens, it rapidly translates into developments in computer science. Actor–network theory tells us it is wiser to remain descriptive of such network, rather than try to explain it.

In some cases, philosophical notions such as freewill may lead to tautologies, where effects are used to justify causes. The disprivileged situation of a minority could thereby be presented as a proof of “unworthiness”. Some stereotypes fail to evolve because they require no verification to be upheld. Bem’s example is a belief in a link between physical appearance and sexual orientation. A man showing feminine features may be classified as homosexual. People who infer such things usually don’t have the possibility to check that their assumption is accurate, and yet will feel that it is, in a perfectly closed loop. As such, evidence plays no role in the survival of the stereotype. Ten years after Bem (Daryl) writes this, Bem (Sandra) devises the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI), a tool used to research gender roles by measuring an individual’s self-perception of androgyny, based on the simple idea that an individual might exhibit both male and female characteristics.[2] Both made gender-role, androginity and sexuality a primary research field for the rest of their careers, and their life is quite a story itself. Recent gender studies detail with greater nuances identity, expression, and biological sex.

[2] I took an online BSRI test (https://openpsychometrics.org/tests/OSRI/) and got high levels of both masculinity and feminity, which Bem consider to be ideal.

Stereotypes are problematic when they limit our understanding of the world. For example, while few people intentionally and deliberately discriminate on the basis of gender, everyone has stereotypes about the characteristics attributed to a given gender. In turn, these stereotypes afford sexist attitudes and behaviours. As explained in chapter 5, these behaviours bolster the stereotypes. Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance claims that, in an attempt to resolve the inconsistency caused by a behaviour (by conflicting with the primitive belief of equality, for instance), chances are that the sexist attitude will turn into a belief system of its own, to legitimate the behaviour.

In order to remain tools instead of becoming cognitive burdens, stereotypes need constant updating. New experiences should rather refine the most relevant characteristics than reinforce the stereotype. Like other first-order primitive beliefs, stereotypes appear as self- evident to us.

Attitudes differ from beliefs: they are affinities for or against situations, people, objects, groups or any other aspect of a situation. They have some roots in our belief system but are often supported by emotional, behavioural, and social influences. Cognitive reasoning plays a minor role in our attitudes. Consider the example:

premise #1 Cigarettes cause cancer, taste bad, and repel others.

premise #2 I dislike those things.

= conclusion I still smoke. [<– attitude]

Many smokers don’t have a cognitive rationale for smoking, yet their final judgment on the matter is positive. We can imagine the many external authorities that may have caused them to evaluate cigarettes positively after all, such as marketing, social allegiance, in addition to the addictive chemical components. As stated before, the ultimate primitive belief very often draws back to senses and cognitive recompense. Desiring things such as hapiness, comfort, and well-being, for oneself as well as their relatives is self-evident and trying to deconstruct a higher rationale for these is difficult. We can trace the outlines of a innate need for self-preservation as well as survival instinct. Rokeach’s list of 18 desirable terminal human values provide an insight on some the most popular western human values. Like attitudes and high-order beliefs, values can be traced back down to reveal their origins in lower-order primitive beliefs. Cognitively, values are seen as an end, not a mean. But one person’s value can be someone else’s attitude. Money, for instance, is seen by some as a mean, and as an end by others.

3. Cognitive dissonance and attitude change

An individual’s intelligence is measured by the amount of uncertainty they are able to withstand.

[Apocryphal]

All things considered, the hidden layers of the making of a belief system closely relate to computationalism. The vertical and horizontal structures, if that’s what they really look like, advocate the idea of a human mind as an information processing system. They also speak in favour of a causal model of the world, though one that is not flowing in a unique direction, but with effects affecting causes. Now that we have a rough idea of how attitudes are formed, let’s look at the way change takes place, and the cognitive dissonance this may produce.

The theory of cognitive dissonance observes the effects produced by conflicting or paradoxical situations in the human mind. It posits that people seek cognitive consistency. It also demonstrates that change in belief can be produced by creating inconsistencies within a belief system. Amongst other possible sources of change, social pressure proved to operate strongly in experiments made by Rokeach in the 70s. They suggest that, when facing contradictions, we tend to change towards the expected socially desirable values rather than what’s perceived as adversarial, even if it contradicts with our beliefs. However, most counter-experiments (that attempt to change subjects towards the socially undesirable direction) have been abandonned, for ethical reasons. A famous, controversial example is the Stanford prison experiment, (ZIMBARDO, 1971) where a group of “guards” subjected a group of “prisoners” to psychological abuse in a mock prison. The experiment was famously abandonned after only six days. A notable artefact (undesirable effect) during the experiment was “demand characteristics.” It is a phenomenon in which participants interpret what is expected from them and unconsciously change their behaviour to fit that interpretation.

In machine learning, an interesting case is that of the YouTube suggestion algorithm, which progressively drifts towards more extreme content. In an essay published by the New York Times in March 2018, Zeynep Tufekci (TUFEKCI, 2018) demonstrated that it is not only true for political content, but for pretty much anything. Videos about vegetarianism lead to videos about veganism; videos about jogging lead to videos about running ultramarathons… Is it possible that YouTube algorithm’s interpretation of users’ interest is the digital version of humans enacting demand characteristics?

One of the main mechanism for consistency that our mind performs is known as rationalization. Social psychologist William James McGuire (MCGUIRE, 2000) describes it as the relationship between “reality” and “desirability.” The more a proposition is believed to be true, the more it will seem desirable as well. “Wishful thinking” is its counterpart: the more something seems desirable to us, the more we will persuade ourselves it is true. The other main consistency-achieving strategies are denial, bolstering, differentiation, and transcendence. The consistencies that all of these strategies produce belong to psycho-logic, not logic. Values and beliefs show psychological consistency that logic contradicts.

Behaviourist theories claim that inconsistencies are the source of change in opinions and values. However, I think there might be opposing arguments. In my experience, inconsistencies are an integral and enduring part of my belief systems. I experience them on a daily basis, and some never seem to evolve towards consistency. Despite my belief in a more egalitarian model of society, I can think of very few occasion where my attitude align. I can, on the other hand, think of many examples where I blatlantly ignore it. This cognitive dissonance has been a part of my belief systems for years. To comment on this with feminist STS theories in mind, aiming to achieve coherence of thoughts seems more like a feature of the researchers and academics who think and write about it, than one that each and everyone cares about. Or, poetically: “There are more things in heaven and earth, cognitive researcher, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.“ Post-computationalism and embodied cognitivism would be the proper framework to examine these strategies of consistency, horizontally calling on situatedness, mental constructs, representations, memory, and perceptual systems.

4. Lie detectors and the contagion of attitudes

Lie detecting technologies measure a body’s response to a lie. Studies in the field of classical conditioning show how such responses are developped from a young age. In western cultures, when children lie, they are usually punished or scolded, and they react with negative physiological features, associated with anxiety and guilt. Those conditioned responses to lying are what lie detectors are able to detect. In other words, a lie is made visible by the discomfort we have learned to express when we infringe the belief that telling the truth is expected from us, and thus desirable. Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s audio documentary The Whole Truth [3] reveals the use of a new kind of voice analysis as a lie method by border agencies and the insurance industry. The artist demonstrates how this allows these authorities to delve deep into the subjects’ bodies.

[3] Available on the artist’s website: http://lawrenceabuhamdan.com/thewholetruth

A parent phenomenon known as “semantic generalization” describes how such conditioned responses can spread between individuals, through language. Preconceptions (and their associated emotional response) can be passed on through verbal means, even if the receiving individual has never experienced the situation before. Thus, all words we use carry their own emotional connotations, from differenciated experiences. Their effect on our belief systems is vertiginous.

5. Self-perception: attitudes follow behaviours

To understand how self-perception works, I need to remember how I was first taught to describe my internal states. For instance, the first time my head felt warm, I’ve been told that it was fever. There is a blind spot between the external observation (fever) and the reality of the state I’m in. Bem explains that when I perceive my own state, I actually perform the process of observing it through someone else’s eyes. Bem states the following: ”In identifying his own internal states, an individual partially relies on the same external cues that others use when they infer his internal states.” I’m unaware that I do so; it must be a zero-order belief. In 1966, Stuart Valins conducted the experiment “Cognitive effects of false heart-rate feedback” and observed this effect. He showed (cisgendered, heterosexual) males pictures of naked women, while pretending to take their pulse. An amplified heartbeat was audible, but was really prerecorded and increased while selected pictures were shown. The subjects were then asked to rate their favourite pictures, demonstrating that their preference depended on what they thought to be internal reactions, but were really predetermined, external authorities.

What does this tell us about values and beliefs? Each of us regularly infers others’ beliefs by observing their attitudes. We assess the motivation behind the attitudes. For instance, “they’re doing it for the money” is a judgement on someone’s attitude, that tells us to not to label it as “sincere”. It is equally true when it comes to ourselves. We are more likely to believe in something if it doesn’t have a consciously associated motivation. My “truest” values are the ones that I chose for no other reason than their innate validity. The fewer incentives, the more it has to be sincere. I nonconsciously perceive my behaviours as indicators of my “true” inner values. This is somehow expressed in the protestant doctrine I was brought up in. Difficulties and challenge are valued, and indicate virtue. If we take into account other bodies’ situation like feminist STS incites us to do, it means that values are at least partially contingent to the affordances of the situation. In a situation where one is unable to enact some behaviours (for legal, moral, technical or societal reasons), they will consequently be unable to develop certain values. On the other hand, in a context where behaviours are enforced, values might be parallely forced upon them. We can observe some similar ideas in Hannah Arendt’s theory of the banality of evil, (ARENDT, 1963) which describes cause-and-effect relationships between affordances and belief systems.

In the theory of self-perception, behaviours and values feel disconnected. I feel that my actions don’t disclose my true values. A number of factors come into play when it comes my attitudes. Cognitive, social, and emotional factors influence behaviours, driving them away from my values. But my behaviours, in turn, influence my values. This equation is best expressed by activists and political leaders, who capitalize on it. Getting people to follow rules first will have the effect of changing consciences, in a second time.

My self-perception tells me that I am capable of formulating independent thinking and that I usually reach a conclusion after I have considered the alternatives. Yet, based on my profile, (gender, class, education, occupation) my highly predictable values say otherwise. Predictability suggests I am far from being as independant-minded as I would hope. Mapping my social influences seems to be equivalent to exposing my major values and beliefs. A social influence can be as benign as a brief encounter with a salesperson (who could modify a simple, high-order belief of the need to possess goods), or a state administration that covertly instills an ideology. I am of a sceptical nature. I walk with doubt. When I hear the opinions I share in someone else’s mouth, I can suddenly see their flaws. Paradoxically, it is possible that sceptisism makes me vulnerable to social influences. Because I believe I am immune to influences I know to be biased, I lower my guard. A quick check of my beliefs informs me that I am aware that ads lie. Despite that, I consume market-dominant brands. My toothpaste says it’s “extra-whitening.” I like the same things as the charismatic personalities I see in movies. I can conclude that there is no loss of persuasiveness because of an influence’s confessed biases.

Finally, the type of influence that seems to have the most effect on belief systems is interpersonal. People influence people. I regard teachers, friends and family as “opinion leaders.” These are fluid roles that each person occupies for a given time and domain of expertise. I might have a “fashion leader,” a “political leader,” a “moral leader,” and so on. One of the undesirable effects of interpersonal influence is the perpetuation of social norms. When an opinion leader shows me the “appropriate behaviour,” he causes me to replicate it. As seen before, the behaviour turns into a value. Bringing change in this situation requires my leader to “update” me. External authorities have the power to limit or expand our beliefs. Inertia or conformism often result from these interdependant nets. Conformity is the foundation of social reproduction. Change is only possible through simultaneity. “Do as I say, not as I do” will not have people “do” anything, because “the things I don’t do” are the ones that set a norm.

The groups I belong to come with unique belief systems, to which I nonconsciously agreed when joining it. To disassociate from them is to risk social disaproval or isolation, through simple classical conditioning, as discussed earlier. Because everyone belongs to several groups, complexity emerges. In addition to being white, I am a 31 year old cisgendered atheist male, educated, a designer, research enthusiast, radical left sympathizer, coming from an upper-middle class, protestant family with no significant dysfunction. Although it is not an uncommon combination, each of these reference groups are characterized by distinct belief systems. Investigating them would probably reveal more similarities than contradictions: people from privileged backgrounds are probably over-represented in pricey art schools as well as in the radical left milieus. I had all the leeway one can dream when it came to deciding on a professional orientation. I can also spot the influences of a white protestant education on most of my political ideology. I can also feel the “reward” of radical thinking, which Bem describes as more likely to convince me that I am thinking for myself. Most groups’ influence works by rewarding those who adopt its norms. They also provide frameworks to bring new perspectives on the world. Undoubtedly, assigned readings, lectures, and contact with faculty members have been agents of change in my values and attitudes over the last few months. Some questions have become salient while others have declined. The one real test of beliefs is that of long-term consequences. A classical example of what this does or doesn’t mean is the conflict most western teenagers find themselves in between family and a college group of peers. The two groups have polarized interests and attitudes. At first, the family group constantly seems to “loose” to the college group. But in the long run, a continuity with the family’s basic beliefs is often observed.

6. From consistency to ideology

Bem invites us to consider the situation where all reference groups align. Without any competition between their respective belief systems, I am no longer forced to actively and consciously determine my own beliefs. If a message is unequivocally broadcasted by religion, family, peers, teachers and mass media alike, the consequence is nonconscious ideology. Bem’s definition of ideology is a serious contribution on Marx and Engels definition of ideology as “false consciousness,” or even on Althusser’s (ALTHUSSER, 1975) more nuanced one of state apparatuses. The theory of self-perception advocate for a psychological state of consistence as the starting point of ideology. Unaware of an alternative, we implicitely accept a belief system. The gender-role ideology has made it tremendously difficult to challenge ideas on gender. During of the 20th century, most radical thinkers focused on the unfairness of discrimination based on skin color. Yet, few were able to see that being female led to prejudices, for the prejudices were “invisible” to them. Values are like theorems: their validity has to be demonstrated. But we behave as if they were axioms, whose legitimacy are assumed and unquestionable.

How impossible exactly is it to find out what my blind spots are? I can see how holding a passport from the “right” provenance is arbitrary. Sadly, as long as external authorities haven’t afforded me to do so, I may not be ready to act accordingly. Growing up, my mother would say she was proud not to understand mathematics and science, while my father knew everything about it. In reaction to the underlying ideology, feminist STS began the examination of science’s biases. Evelyn Fox Keller’s book Reflections on Gender and Science (KELLER, 1985) stated how this unbalanced representation resulted in wrong results. (i.e. our underfitting machine learning model) The attitudes that gender-role ideology affords precludes access to certain human terminal values (i.e. self-respect, fulfillement, accomplishement). It leads a majority of female-gendered individuals to end up in a limited number of roles. The ideology dictates both the amount of alternative options and the motivation to choose amongst them. Equality does not require an equal amount of each group to be represented in every role; It requires that the variation in outcome reflects the variation in individuals, regardless of gender.

These issues sound like they are more adressed in today’s society, maybe because the acting agents of the gender-role ideology progressively stop to be invisible. But as evidenced by earlier examples, this could also be a “false consciousness,” limited by my own reference groups and accessible data. Consider how a “progressist,” heterosexual relationship with a high degree of equality reveals the presence of the ideology: If I were to stay home to look after children while my partner has a career, I would be praised for my thoughtful exercise of “power”, while my very right to that power would remain unquestioned.

Some drawbacks come with the construction of masculine identities. Tenderness and sensitivity have only become “affordable traits” in my late twenties. Adrienne Rich (RICH, 1982) developped the theory “Compulsory Heterosexuality,” describing unexpected consequences of the gender-role ideology. Teresa de Lauretis (DE LAURETIS, 1987) describes ideologies as “neither freely chosen nor arbitrarily set,” leaving the door open for provoked changes. Foucault’s theory of sex describes gender as the set of effects produced in bodies, behaviours, and social relations. De Lauretis adds to that list: “the process of bio-medical apparati, and social technologies.” In relation to these “technologies of sex,” Louis Althusser’s list of the ideological state apparati also include the media, schools, the courts, and the family. De Lauretis critically extends it to the academy, the intellectual community, the avant-garde artistic practices, radical theory, and feminism. She refers to our times (or those of 1987) as “cultural narratives” who need “rewriting.” She claims that “all of western art and high culture is the engraving of the history of gender construction.” Can we think of a western art that would engrave a different history? How could self-perception afford the rewriting of our times? What could a strategy for revealing unwanted external authorities look like?

7. Unravelling external authorities with nonhuman witnessing

As we have covered the basis of the mechanisms behind system beliefs, value-making, attitudes, and ideology, I would like to embrace a speculative approach to try and consider if and how technology might influence these cognitive constructs. In the first term’s group project, we talked about the the sense of touch, and how a mid-air haptic technology could reconfigure it in the future. We claimed that–in the event that mid-air haptics managed to achieve multimodal sensory interaction convincingly–our primitive beliefs could end up seriously affected. What other emerging technologies would have the potential to inform, affect or modify our belief systems?

Whilst agriculture as we know it is dying, the collection and harvesting of databases is becoming the most profitable industry in neoliberal history. It has been a few years only that the primary purpose of connected objects and internet based services is the creation of global and small-sized databases. In the documentary Story Telling for Earthly Survival, Donna Haraway says that “the best science, is that which knows its past, and is willing to be accountable to its futures.” In her life’s work, she has invited us to think of life through the language we use to describe it. In self-perception theory, an abundant pictorial language is used to describe the agents at play. External authorities can be human or nonhuman. [4] All these agents take shape or leave traces in the digital world. Social medias and connected device are permanently witnessing to our behaviours. If attitudes follow behaviours, and if we’re all as predictable as I am, could these devices already hold the data necessary for a digital and external look at ourselves?

[4] Althusser’s ideological state apparatuses include: media; school; courts; and family. Technologies of sex as informed by de Lauretis and Foucault include: interpersonal influence; social technologies; bio-medical apparatuses; academy; the intellectual community; the avant-garde artistic practices; radical theory; and feminism.

The accuracy of machine learning’s predictions is constantly improving, by leveraging these previously unattainable databases. There’s plenty to be less than enthusiastic about the fact that these methods are mainly being developed by huge corporations that pursue profit at the expense of any sustainability. In STS, this is best described by the “tragedy of the commons” theory (HARDIN, 1968): A limited amount of agents use a shared-resource to their own self-interest and behave contrary to the common good of all users. Algorithmic decision-making is one of most important ongoing discussion. An important step towards accountability was made in the US last month with the enactment of the “Algorithm Accountability Act of 2019.” [5] Personal databases are already a reality. It is only a matter of time before the first young adult will have a complete acess to a comprehensive archive of their entire life’s attitudes and behaviours. I’m speculating that this gives us the opportunity for an unprecendented computational-epistemological reflexion.

As seen in Valins’ experiment (the one with the sexy pictures and the pre-recorded heartbeat), witnessing our own attitudes has a great effect on our choices and opinions. Based on the idea developed in chapter 2 that a more informed decision is less likely to underfit, gazing at maps of our belief systems could both inform and update our stereotypes.

I offer no precise model as to how this could be achieved. But neural networks have the potential to render large amounts of data intelligible. By mixing several strategies in similar ways than human minds do (generalization, stereotype, abstraction…), these nonhuman agents greatly outperform other statistical models. This gives ground to believe that in the future, models could be trained on large and small personal databases and turn them into precise mappings, clustering our values in a way self-perception prevents us to. I think there is a case for nonhuman witnessing to help us gain perspective. Data and machine learning carry the bizarre, sci-fi-like promess of a personal value checker.

Roman Krznaric dubs the 20th century as “the age of introspection.” Could our futures be those of outrospection? In the short animated video I made to accompany this proposition, I tried to put in images several concepts explored throughout the essay. I used conditional adversarial networks to generate images with models I trained on some of my own external authorities. The list is subjective and very ill-considered, but it aims to represent external authorities as technologies of sex (described by de Lauretis and Foucault) and Althusser’s ideological state apparatuses:

— I trained two models on Disney’s movies extracts (Cinderella and Beauty and the Beast) and one on John Travolta in Pulp Fiction, to represent medias and artistic practices.

— I trained a model on Emmanuel Macron’s speech after Notre-Dame’s fire to embody political ideologies and state apparatus in general.

— A model was trained on my partner to embed interpersonal influences.

— A model was trained on an interview of Hannah Arendt, who represents schools, academy, the intellectual community, radical theory, and feminism.

— And a model was trained on images of me, to situate myself as the subject of inquiry whose external authorities are being “mapped.”

The weird-looking, dreamy esthetic of the generated animation fits the idea of reconstructed bits of memories taken from my past. The dialogues feature questions inspired by the work of artists Fischli & Weiss on cod philosophy and express my self-perceived concerns. The sound finishes with results from a personality test, meant to represent technology-informed intelligence on my beliefs.

If you believe in “Seeing then”, or if you’d like to watch it again, you’re invited to visit the following url and see the 3’39 animated video that resulted from these speculations:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MyYrxyZ2npo

In order of appearance: the “Macron” model (political ideologies and state apparatus); the “Arendt” model (schools, academy, the intellectual community, radical theory, and feminism); the “Travolta” model; the “Beauty and the Beast” model; the “Cinderella” model (medias and artistic practices); the “my partner” model (interpersonal influences); and the “Julien” model (situating myself as the subject of inquiry)

Annotated bibliography

FESTINGER, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance informed me on the existing, arguably behaviourist framework from which Daryl Bem builds his own self-perception theory. While Festinger’s theory tends to generalize behaviours and to assume based on external expressions, Bem further describes the inner states of the state of cognitive dissonance. Festinger’s earlier version of the theory remains relevant when looking at consumer behaviour, on which Bem didn’t focus. BEM, D. J. (1970). Beliefs, attitudes and human affairs. Monterey Calif, Brooks-Cole. Bem’s book offers a comprehensive deconstruction of the main cognitive mechanisms at play in the construction of belief systems. It describes the different layers of beliefs, (zero-order, first-order, high-order) their vertical and horizontal structures, and expands on their evolution towards attitudes, behaviours and ideologies. Bem’s theory of self-perception draws on Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance, offering an alternative intepretation of change in attitude. I used self-perception theory for the most of my research. I used a few examples borrowed from Bem, and tried to find up-to-date ones whenever relevant. I did contact Dr Bem, in the hope to have him comment my speculative ideas on technology. While our first exchange was promising, I did not get an answer after I actually sent him my questions. I suspect that he got bummed by my wacky, sci-fi like stories.

FOUCAULT, M. (1997). Histoire de la sexualité. [Paris], Gallimard.

In Histoire de la sexualité, Foucault analyzes the paradox between the language on sexuality in western cultures with the attitudes. By looking at the topic is talked, he is able to trace the psychological process of an entire society. Sexuality is perceived as a private, intimate subject. Foucault demonstrates that religion and state have managed to make it a controlling and a repression device, while maintaining popular belief in intimacy. He develops the idea of “technology of sex,” and how they paved the way of gender-role ideology. Foucault describes gender as “the set of effects produced in bodies, behaviours, and social relations.” As such, it allows me to bridge some of these effects with attitude and behaviours as described by Bem.

FOUCAULT, M. (2007). Surveiller et punir: naissance de la prison. [Paris], Gallimard. While not directly linked to my subject, I found a useful example in Foucault’s book on the history of prisons in the west. Generally, I feel inspired by the book’s gaze on authority, state apparati, and social influences. Foucault’s work also informed my research on subjects such as conformity and self-representation.

DE LAURETIS, T. (1994). Technologies of gender: essays on theory, film, and fiction. Basingstoke, Macmillan.

In her book, Teresa de Lauretis examines Foucault’s theory of sex, and updates them with intersectional feminist perspective, accounting for a broader definition of both gender and class. Foucault’s theory of sex proposes that gender, both as representation and self-representation, is the product of various social technologies such as cinema (medias), institutional discourse and critical practices. de Lauretis points out that Foucault’s main flaw is to ignore the differenciated sollications/experience of male and female subjects. She draws on Evelyn Fox Keller critique of genderization in science to comment on the attachments and implications of “en-genderization,” an intersectional experience of class, sex and race. She critiques western art and high culture and expands Louis Althusser’s definition of ideological state apparatuses. In doing so, I found similarities with Bem’s definition of ideology as the moment where all external authorities align and concur.

Additional references

MATURANA, H. R., & VARELA, F. J. (1992). The tree of knowledge: the biological roots of human understanding. Boston, Shambhala.

ROKEACH, M. (1973). The nature of human values.

HILL, S. (2016) ‘Is VR too dangerous for kids?’, Digital Trends. https://www.digitaltrends.com/virtual-reality/is-vr-safe-for-kids-we-asked-the-experts/

ZIMBARDO, P. G. (1972). The Stanford prison experiment: a simulation study of the psychology of imprisonment conducted August 1971 at Stanford University. [Stanford, Calif.], [Philip G. Zimbardo, Inc.].

INFOBASE, & TED (FIRM). (2018). TEDTalks: Zeynep Tufekci—We’re Building A Dystopia Just To Make People Click On Ads. https://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?xtid=160849.

MCGUIRE, J. (2000). Cognitive-behavioural approaches: an introduction to theory and research. Liverpool, Liverpool University.

ARENDT, H. (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: a report on the banality of evil. London, Faber and Faber.

KELLER, E. F. (1996). Reflections on gender and science. New Haven [u.a.], Yale Univ. Press.

RICH, A. (1982). Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence. Denver Co, Antelope Publications.

HARDIN, G. (1968). ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’. Science. 162.

ALTHUSSER, L. (1975). Idéologie et appareils idéologiques d’Etat: Notes pour une recherche. Villetaneuse, Centre de reprographie de l’Université Paris-Nord.