Hyperrealistic Portrayals of Nature and Natures Contemporary Redefinition through New Media Art

produced by: Oliver Schilke & Karen Okpoti

The return to a symbiotic relationship between man and the natural world seems to be unattainable. Yet here we consider how the aesthetic of nature in new media art can have an impact on the way we understand the natural world. Our analysis presents nature as hyperreal, a conception of nature constructed into a form that is easy for human consumption. As such the experiences of nature become moderated so that its intrinsic meanings only become a simulation of reality.

We will channel these ideas through envisions our cities integrating nature influenced art into their structure and build a speculation on how through this amalgamation could have an impact on environmental awareness creating in itself a form of environmental education.

Nature as Hyperreal

Leather and Gibson analyse hyperreality as the theory on how we construct and “simulate” reality – drawing on philosophy, sociology, semiotics, history and media studies[i]. An individual’s preference for illusory objects over authentic ones[ii].

In the modern Anthropocene, the natural world is commonly conceptualised as something which can be engineered to our immediate needs and reduced to raw materials. It is important recognise how these ideas of hyperreal natures has engrained themselves in present-day culture.

The hyperreal has the ability to create a simulation of nature which is not the real nature, but an imitation based on our idealistic conception of the idea of nature, a perversion of reality. It is that way that it interprets the entire world, stopping people deterring people from recognising what is true and what is not. Hyperreality must always rely on asserting its “realness”[iii].

Hyperreality in Art

Hyperreal nature is not a new phenomenon in art. From artists like Turner and Ruskin it has been portrayed as a healing and spiritual force, painting images of a wild and emotive scenery.

In a hyperreal context one might ask which becomes preferable the natural world or the “pure” and “unspoilt” depictions of nature that are translated through this medium. Does holding onto these ideas avert the suffering and absolve us of cruelty[iv]. There is always a danger of taking any image or model too literally[v].

Contemporary Re-definition of Nature

Through climate and ecological collapse, our estranged relationship with nature is being dramatically redefined, forcing us to re-evaluate the way in which we understand, define and interact with it. Welsby states, that the idea of an ontological shift in the way we see ourselves in relation to nature is no longer a matter of speculation[vi]. Social media and shows such as Blue Planet 2 have had a big impact on this realisation, helping break down the hyperrealities that surround it.

Taking this into consideration we can begin to think about how this realisation is manifesting itself in present-day new media art. Contemporary environmental artworks often convey a notion of the world as ‘a place for interaction and connection’[vii]. A lot of these works are created with the motive to raise awareness of our natural surroundings.

Art has its own distinct status in the world and offers alternatives to resist and combat hyperreality[viii], so it can be stated that focusing a user’s attention toward nature in his or her daily life using human-computer interaction technology is a key challenge of human-computer-biosphere interaction[ix].

Case Study

‘Ocean is Air’ by Marshmallow Laser Feast[x] is a project we would like to use a case study. This project is “a multi-sensory immersive installation illuminating the fundamental connection between animals and plant”. The intension of this project gives the viewer an “opportunity to not only learn about the symbiotic systems of nature, but also to experience it first-hand.”

The emphasis is placed on the conscious awareness of the process of representation and not the representation itself[xi]. What it generates are experiences and learning opportunities that are realer-than-real, generated from ideas and are not the symbolism of nature[xii].

Biomorphic Architecture

The inspiration for our artefact came from our research into Biomorphic architecture. It is suggested by Joye that we have reason to believe the human brain is adapted to processing natural settings and objects[xiii], and through this architectural design that is based on natural forms can enrich the human relationship to the built environment. Joye also goes on to propose that a possible effect of widespread biomorphic architecture has the effect is of subtle shifts in human thinking and could be understood as a robust form of environmental education[xiv].

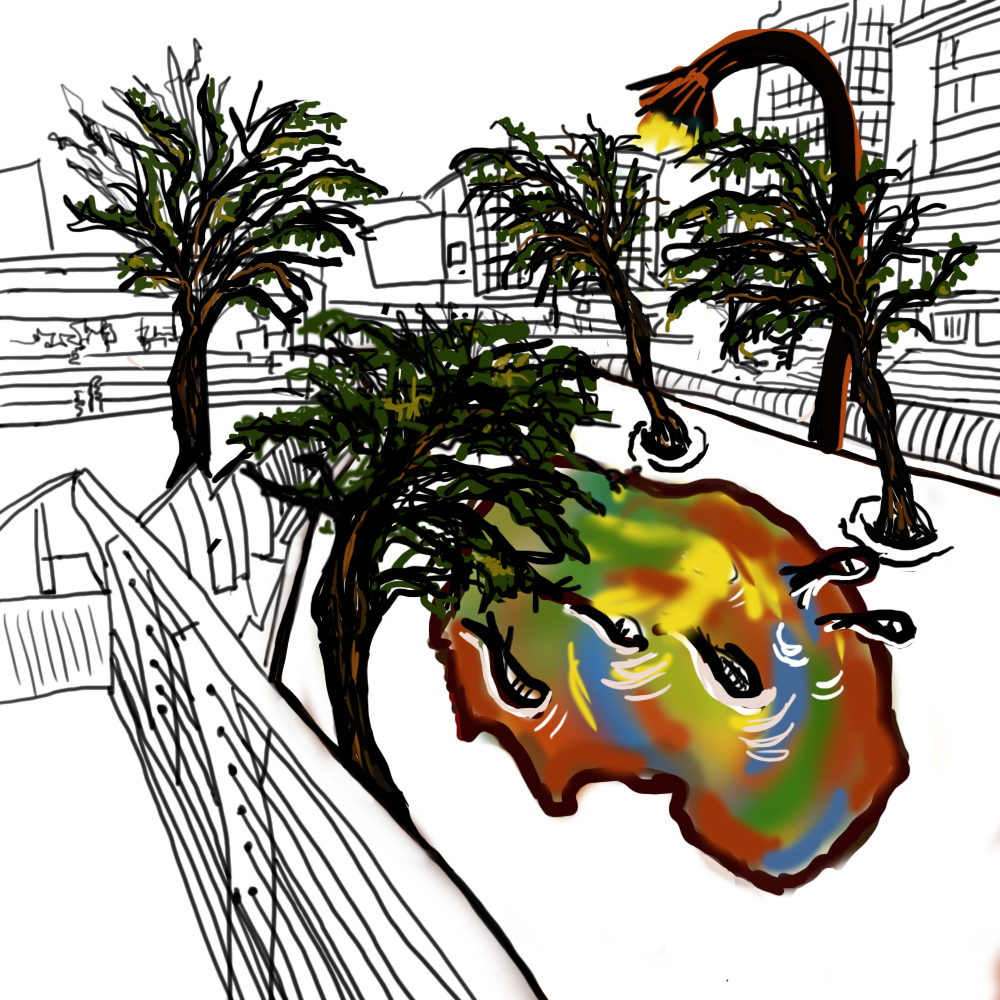

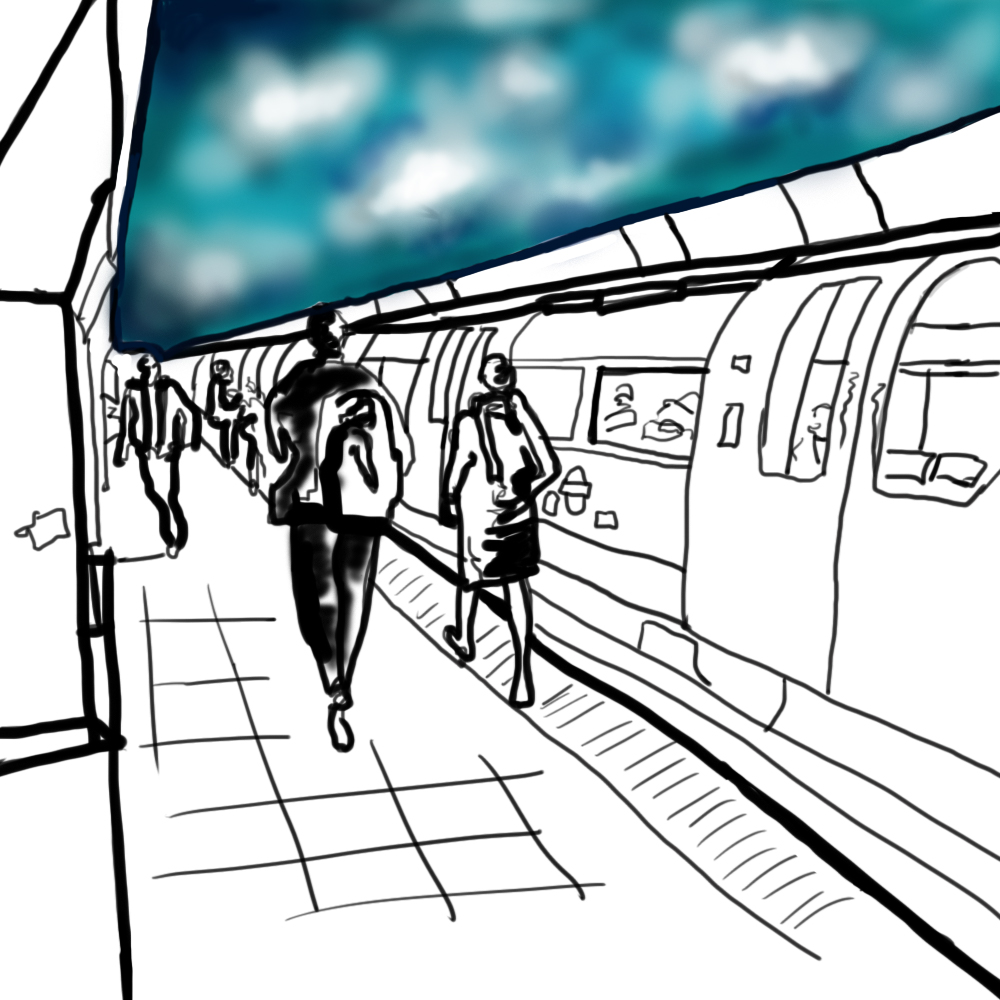

Artefact

Our artefact envisions a future where the nature influenced forms of new media art have matured and become ubiquitous in our cities. We feel that providing people with the perception of being close to nature can be used to promote conservation[xv].

The use of technology in this way could be understood as a form of communication, building interaction with the self[xvi] and encouraging one toward a state of understanding. This change of pattern in people’s environment could be linked to behaviour and therefore start to engage people in dialogue about impacts[xvii].

These forms of generative art, interactive sculpture, holographic projection (to name a few) could lead thought into the natural world and environment, while also creating a spectacle of experience that can remind people of the value of their place.

Conclusion

An approach needs to be taken to build further understanding of the learning opportunities these experiences can create using these innovative approaches. Considering possible artworks as a form of environmental education could be a dynamic and influential way of building further understanding and compassion for the natural world.

This being said what needs to be considered is that if art takes a non-didactic approach does it in turn build upon the ideas of hyperrealistic fantasies of nature. Artists must consider how their work in relation to nature will impact the viewer. Nature in art can easily be misrepresented and in turn misunderstood. Imagination and experience, manifest with the ability for people to define meanings of nature for themselves[xviii].

References:

[i] Mark Leather and Kass Gibson, ‘The Consumption and Hyperreality of Nature: Greater Affordances for Outdoor Learning’, Curriculum Perspectives 39, no. 1 (April 2019): 79–83, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-019-00063-7.

[ii] Garen J. Torikian, ‘Against a Perpetuating Fiction: Disentangling Art from Hyperreality’, The Journal of Aesthetic Education 44, no. 2 (2010): 100, https://doi.org/10.5406/jaesteduc.44.2.0100.

[iii] Garen J. Torikian.

[iv] Liam Campbell, ‘IS HYPERREALITY CONSUMING NATURE?’, n.d., 4.

[v] Julian Voss-Andreae, ‘Quantum Sculpture: Art Inspired by the Deeper Nature of Reality’, Leonardo 44, no. 1 (2011): 14–20, https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_00088.

[vi] Chris Welsby, ‘Technology, Nature, Software and Networks: Materializing the Post-Romantic Landscape’, Leonardo 44, no. 2 (April 2011): 101–6, https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_00113.

[vii] M. Marks, L. Chandler, and C. Baldwin, ‘Environmental Art as an Innovative Medium for Environmental Education in Biosphere Reserves’, Environmental Education Research 23, no. 9 (21 October 2017): 1307–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1214864.

[viii] Garen J. Torikian, ‘Against a Perpetuating Fiction’.

[ix] Hill Hiroki Kobayashi, ‘Research in Human-Computer-Biosphere Interaction’, Leonardo 48, no. 2 (April 2015): 186–87, https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_00982.

[x] Marshmallow Laser Feast, Ocean Is Air, n.d., https://www.marshmallowlaserfeast.com/experiences/ocean-of-air/.

[xi] Welsby, ‘Technology, Nature, Software and Networks’.

[xii] Leather and Gibson, ‘The Consumption and Hyperreality of Nature’.

[xiii] Yannick Joye, ‘Cognitive and Evolutionary Speculations for Biomorphic Architecture’, Leonardo 39, no. 2 (April 2006): 145–52, https://doi.org/10.1162/leon.2006.39.2.145.

[xiv] Joye.

[xv] Kobayashi, ‘Research in Human-Computer-Biosphere Interaction’.

[xvi] Oliver Gingrich et al., ‘Transmission: A Telepresence Interface for Neural and Kinetic Interaction’, Leonardo 47, no. 4 (August 2014): 375–85, https://doi.org/10.1162/LEON_a_00843.

[xvii] Marks, Chandler, and Baldwin, ‘Environmental Art as an Innovative Medium for Environmental Education in Biosphere Reserves’.

[xviii] Leather and Gibson.