The View From Down Here

An interactive LED wall which interrogates the surveillance mechanism of Google Street View.

produced by: Giulia Monterrosa

“Maps are cultural artefacts that are deeply implicated in the history of ideas; intrinsically linked to our conceptualisations of space; and inform our political and personal subjectivities”

(Strom, 2011)

"The View From Down Here" is a response to a case study around the social, political and cultural aspects of Google Street View. It aims to open a discussion regarding the ways in which Google appropriates an immense corpus of data, questioning the copyright issues that arise as a result. Finally, it looms over us as a grim reminder that the notion of “privacy” in public spaces has been rendered obsolete. This interactive installation exhibits hundreds of shadows of Google’s employers, collected whilst digitally wondering around the streets of London - the most surveilled city in the whole world - in a self-contained, archival project of imagery from the virtual afterlife of data. The 300 beady red eyes of "The View From Down Here" capture the silhouette of the viewers and interrogate the unwilling agency they perform in the Information Age.

Are we not all part of some surveillance structure? Could we escape the engaging nature in which technology is presented to us? Could we stop, observe, and question the aftereffects?

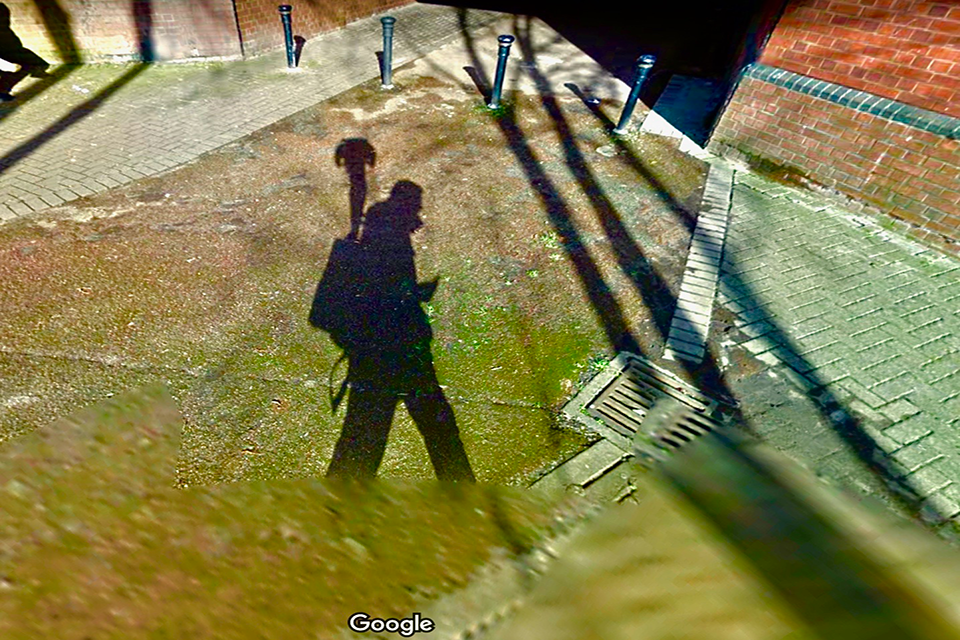

Screenshots from Google Street View for "The View From Down Here".

CONCEPT AND BACKGROUND RESEARCH

Google Street View is a technology that appeared in 2007 and is featured in Google Maps and Google Earth, providing 360° interactive panoramas of many streets around the world. Throughout the years it has substantially evolved, enhancing Google’s mission to organise the world’s information by making it universally accessible and useful. It offers vast amounts of qualitative urban information that is both spatially referenced and temporally revisited. Not only it helps users to preview and explore places nearby or across the globe, but it also offers the possibility to get live tours of museums and other interior places such as restaurants, cafes, offices etc. Most photography is done by car, but also by tricycle, boat, snowmobile, and underwater apparatus, as well as on foot.

Who is behind it? The imagery offered by Google Street View is collected by employed drivers or professional photographers, but can also be crowdsourced and provided by the public.

Privacy?

Google declares that the photos taken from them are public property - hence, no violation.

How could we assert if something is violating our privacy rights in public spaces? Is the fact that we have not been captured - yet - by the 6 eyes cameras of Google enough for us not to care?

By inhabiting our environments, contributing with meanings, stories, values, we are producing infinite profit for Google to capture. The big corporation, which owns the monopoly of digital maps, appropriates and thrives on the ways in which we move and discover our surroundings - without having to pay for a thing.

Nonetheless, a plethora of issues arose as early as 2008 - only one year after the launch of the platform - when many individuals, as well as entire governments, such as Germany and Austria - have sued the company for taking photographs which pictured them or other citizens engaging in activities that they do not wish to have published online - people leaving strip clubs, protesters at an abortion clinic, sunbathers in bikinis, cottagers at public parks, people picking up prostitutes (MacDonald, 2007). Following these allegations, Google has responded by introducing the blurring filter technology which obscures the faces of pedestrians. Along with these, most military and defence facilities, as well as some private homes, appear as blank or pixelated places, demonstrating an imbalance of power within this surveillance mechanism.

A vast part of my theoretical research draws upon an interesting essay that the activist and conceptual artist Paolo Cirio (2012) has written in regards to this topic. Cirio accuses Google Street View to have crossed a biopolitical surplus (referring to the notion of biopolitics by Michael Foucault, where life cannot be understood outside political process, being the object and effect of political strategies). With great endeavor, the artist identifies said surplus as a discrepancy of the Information Warfare, where an advantage of tactical information can manipulate and disrupt who is most vulnerable - civilians. The info-war becomes a record of battles between corporations, governments, civilians, and algorithms, constructing a virtual afterlife of misappropriated data which will be in the digital world forever.

Archival Art

The aesthetic values of Google Street View have been well acknowledged and treasured amongst many artists, who have unveiled moments of human behaviours that have accidentally been captured as a result of the Information Age. Some memorable works are "A Series of Unfortunate Events" by Michael Wolf, a photographic collection of weird, fascinating fragments that provoke thought and discussion. "A New American Picture" by Doug Rickard, which is a search for the sublime into the virtual, forgotten, economically devastated, and largely abandoned American Streets. "No Man’s Land" by Mishka Henner, who used Street View to collect misappropriated images of roadside prostitutes in Italy and Spain, uniquely addressing the uncomfortable collision of public and private space, that is yet always easily accessible.

Photo 1 and 2 from "A Series of Unfortunate Events" by Michael Wolf (2010). Photo 3 and 4 from "A New American Picture" by Doug Rickard(2010). Photo 5 and 6 from "No Man’s Land" by Mishka Henner(2013).

What, exactly, is it about Google Street View that makes it so appealing to creative types? Could it be considered art, appropriation, visual sociology, journalism ?

Ingraham, C. & Rowland, A. (2017) point to Donna Haraway "God’s Trick", the impossible desire to see everything. Google’s imagery becomes so appealing because of its disembodied, neutral and objective perspective, where the world is seen and perceived as it is: a sincere exploration of cultural meanings.

As I was digitally wondering around my neighbourhood, in the process of investigating the connotations that can transpire within the platform, I noticed on the pavements the shadow of one of Google’s employers, roaming the streets of Rotherhithe, immortalising the scenery with their lens.

And so I started noticing these shadows more and more, the ghostly presence of virtual bodies and their machines haunting the real world.

And just like this, the unassailable nature of Google’s God’s-eye-view collapses as the human presence behind it becomes evident. The labour of its employers demystifies the technology, and their shadows unveil the collateral damage and the casualties caused by Google's monopoly.

Shadows of employers with set routes to follow within a certain schedule, every day, every week, who know little to nothing about the technology they are operating with (McNeil, An interview with a Google Street View Driver, 2015). Or the public, who decides to contribute by providing its own personal imagery in exchange of virtual trophies.

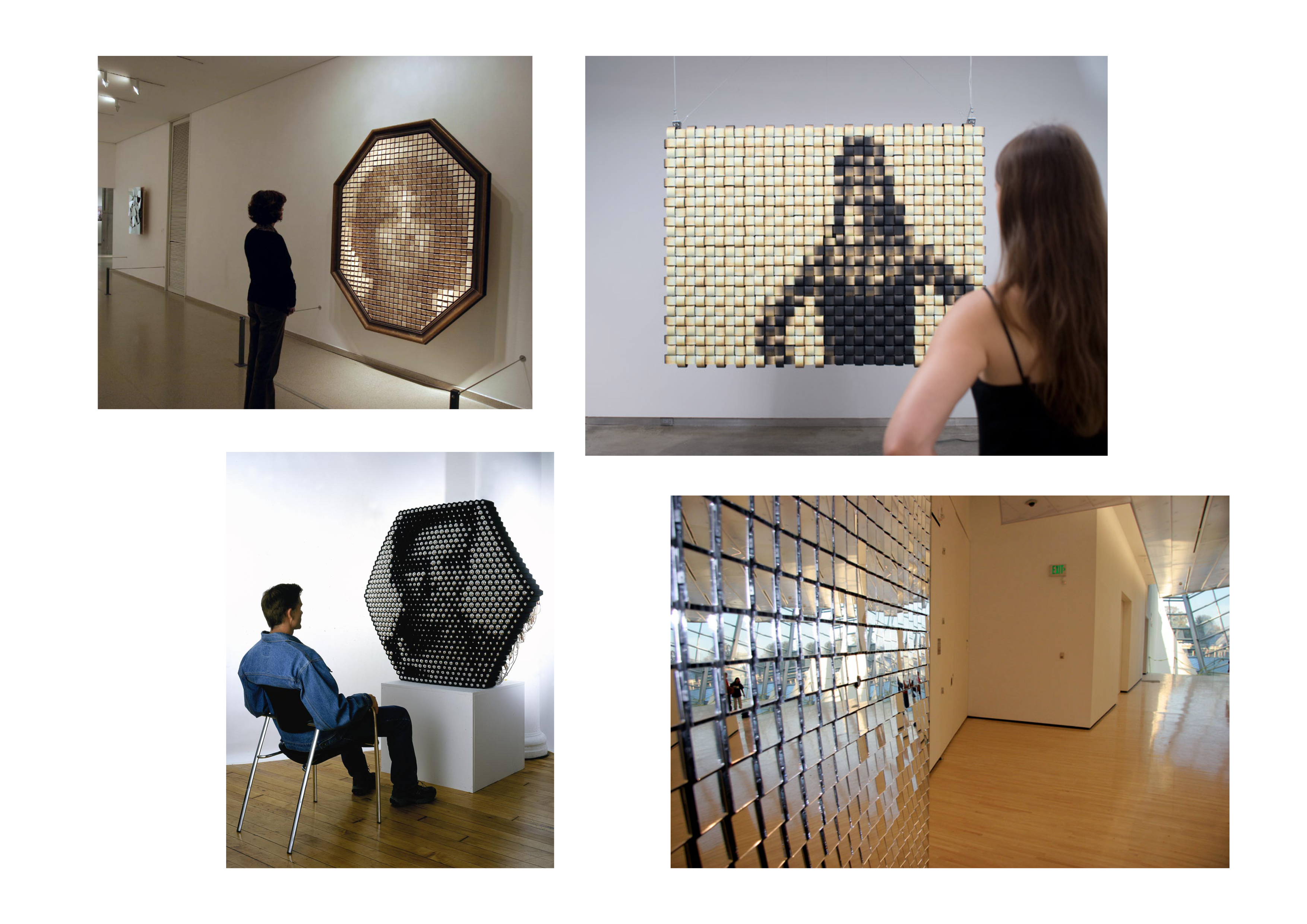

And just like Google Street View does, I wanted my archive to be able to respond, change and depend on the presence of the viewer. I was inspired by kinetic artists (like David C. Roy or George Rickey), but mainly and most importantly by the art of Daniel Rozin, who creates mechanical mirrors with a wide array of materials. Another impactful stimulus was Sinusoidal Noise by Kai Lab, who created a study of movement in sinusoidal noise through lights.

Daniel Rozin's interactive mirrors.

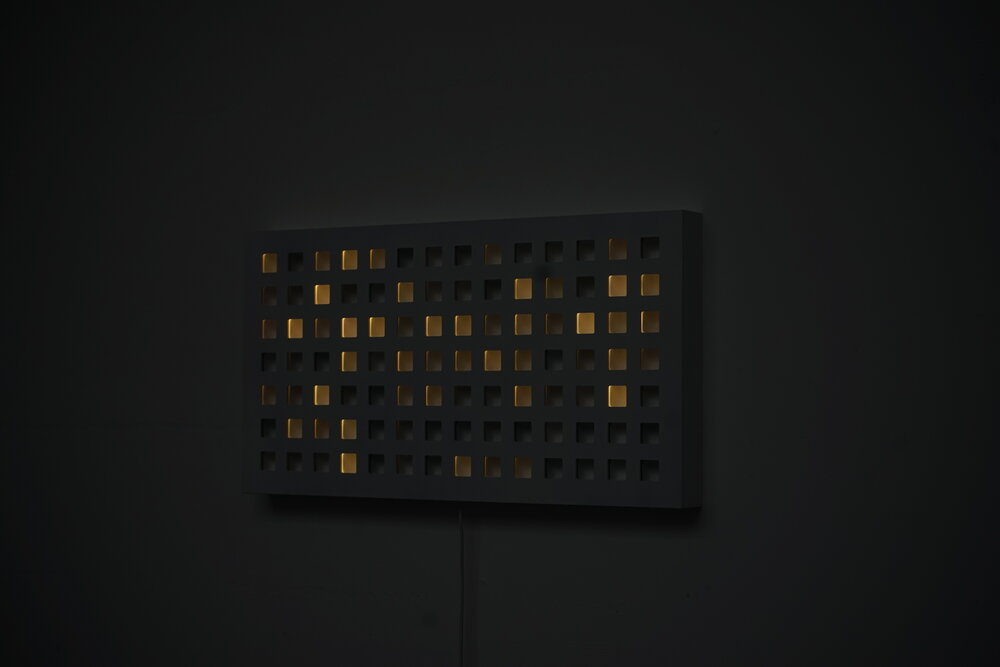

Sinusoidal Noise by Kai Lab.

TECHNICAL

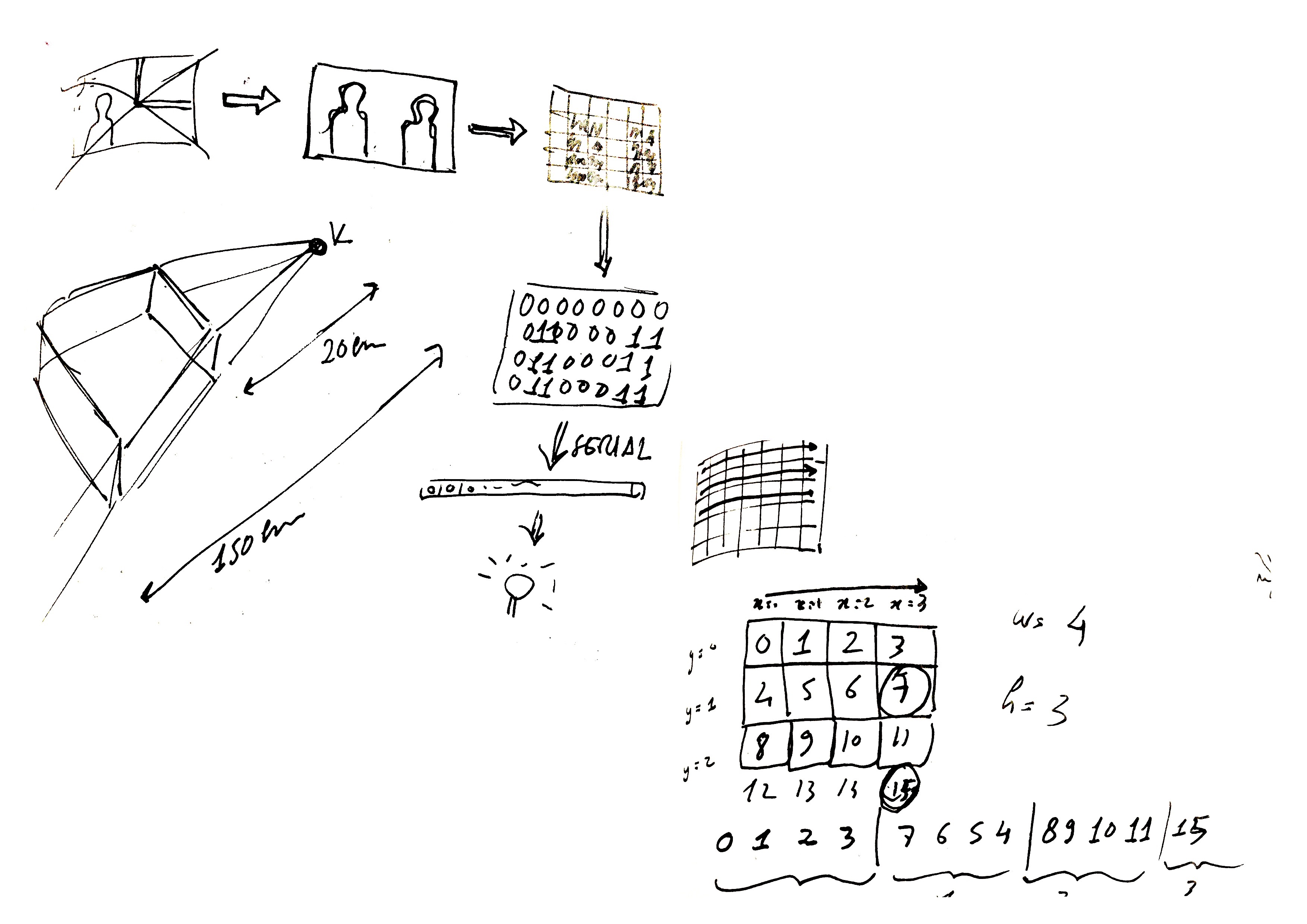

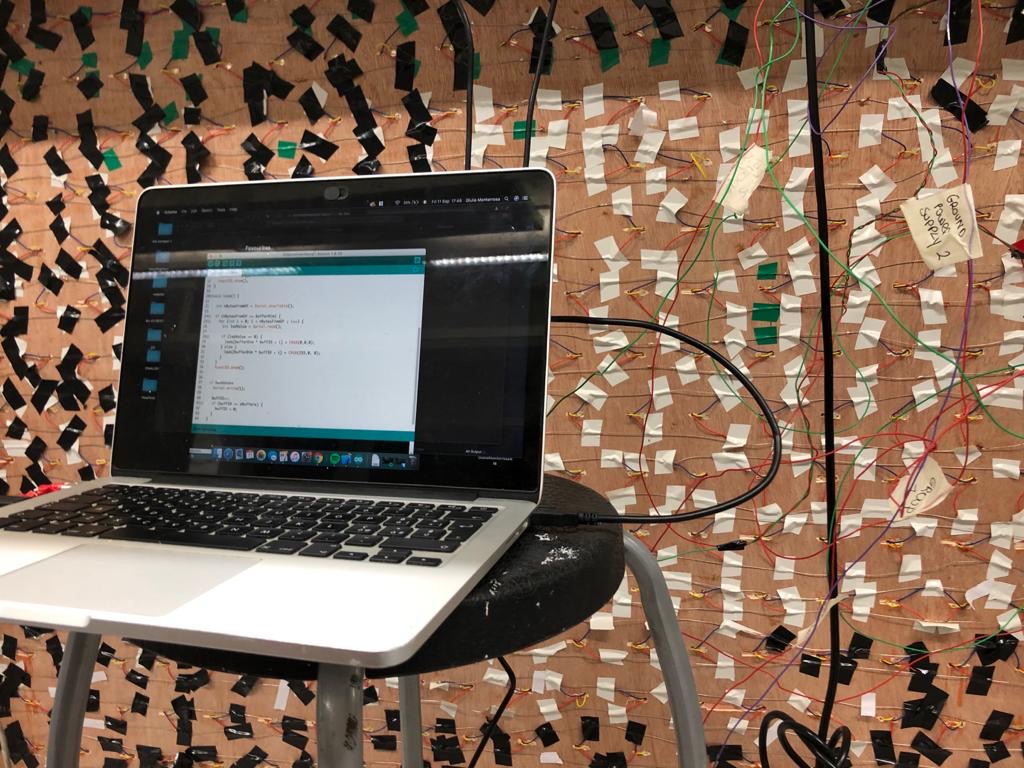

This interactive piece consists of 300 individually addressable LEDs controlled by Arduino, which receives serial messages from an openFrameworks programme that collects depth values from a Kinect camera. The whole programme runs on a RaspberryPi. After doing some testing on code, I have decided to settle with 300 LEDs, on a grid of 20x15 and aspect ratio of 1.3 (same as the Kinect), in order to attain a good definition of the silhouette of the person, yet creating a pixelated effect which could be feasible to manually realise.

Serial communication handshake between OF and Arduino.

Software

The OpenFrameworks programme scans through the depth pixels detected by the Kinect. It creates a grid of 300 squares, saving the overall brightness value of each, which defines the distance of the objects from the camera. The image that the Kinect draws is quite pixelated, but it can capture shapes and movements.

I wanted to simplify the electronics side of the project as much as possible, putting more work on the software. The values are stored on a buffer in a serpentine order: instead of going from left to right for each row, all the even rows will draw and save values from the opposite direction, hence from right to left. In this way, I have definitely facilitated the soldering of the LEDs and the jump from one row to another.

Another challenge that I encountered was when creating a handshake serial communication with Arduino. Arduino Leonardo can only receive 64 bytes per message, thus I had to create a buffer size of 60, and divide the 300 values stored by the Kinect to be sent in 5 separate messages. After each single message, Arduino sends a message to OF, guaranteeing a consistent communication between the two softwares. Fortunately, the speed in which the messages are sent is so fast that it is in fact not perceptible.

I have then uploaded the OF programme on a RaspberryPi.

Kinect's depth image on openFrameworks. Pixelating the image.

Physical Computing

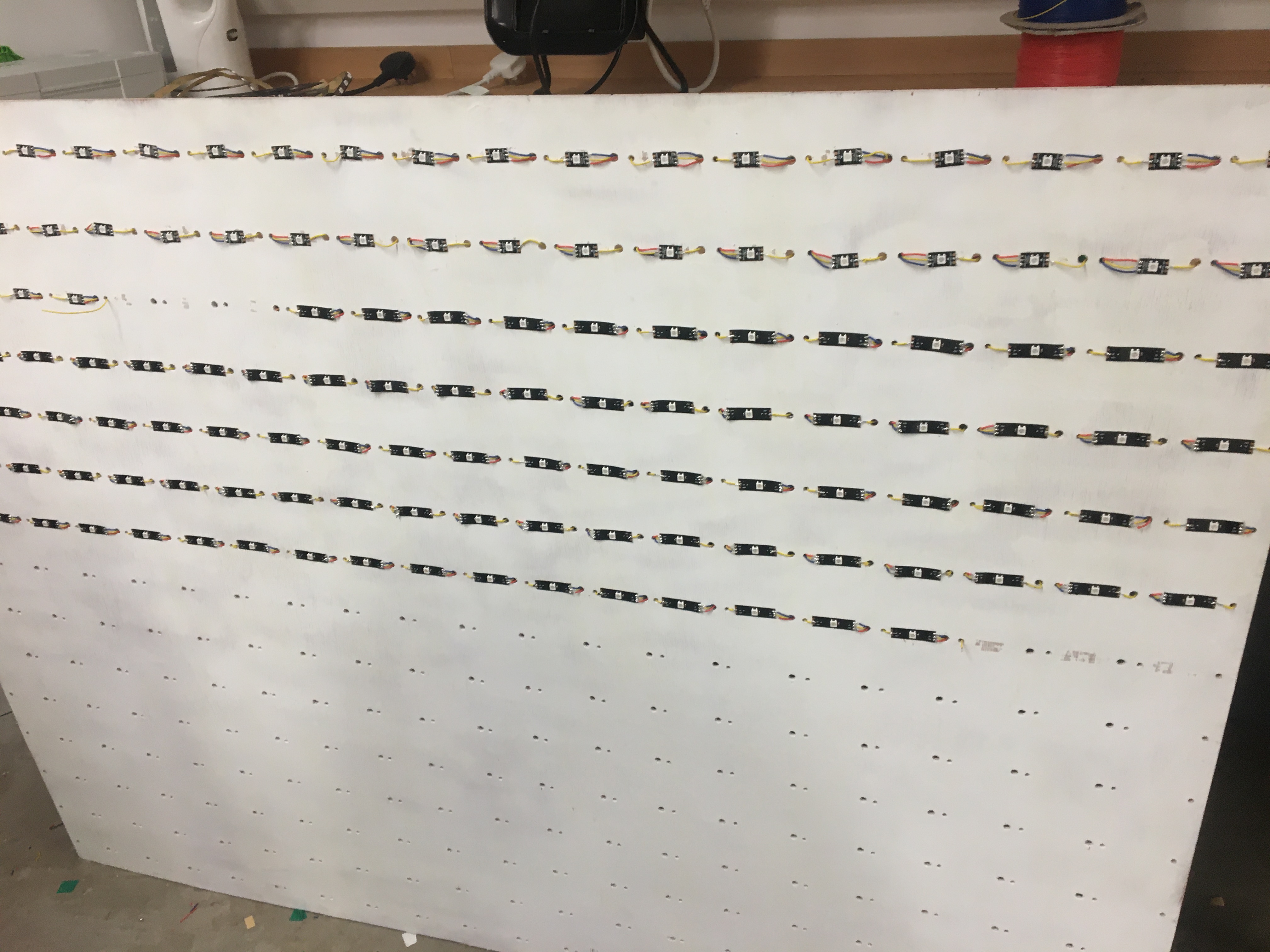

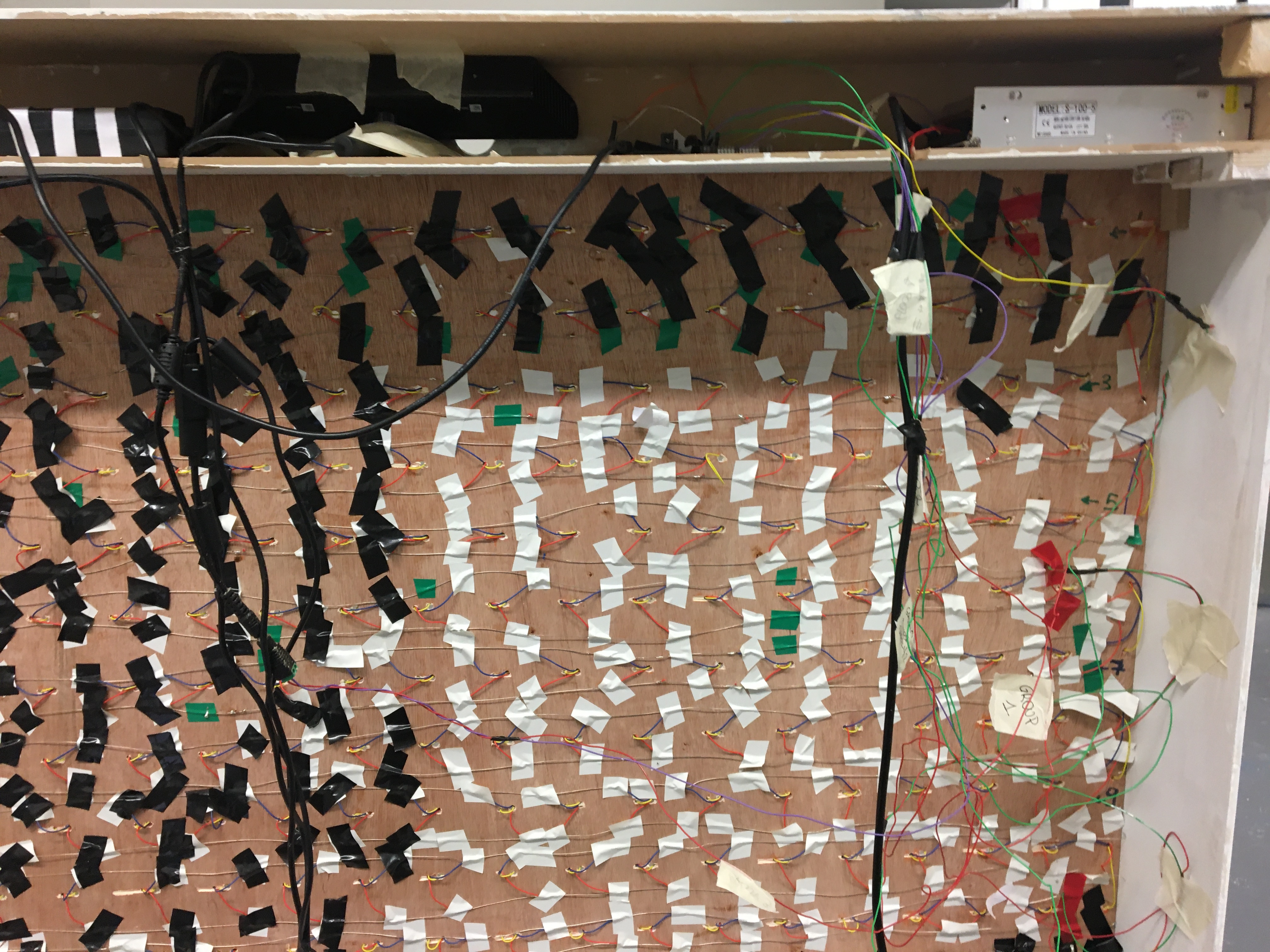

All 300 WS2812B LEDs have been individually cut, separated, and then re-soldered to one another in a parallel circuit, giving me enough margin to address and position an image on top of each one of them.

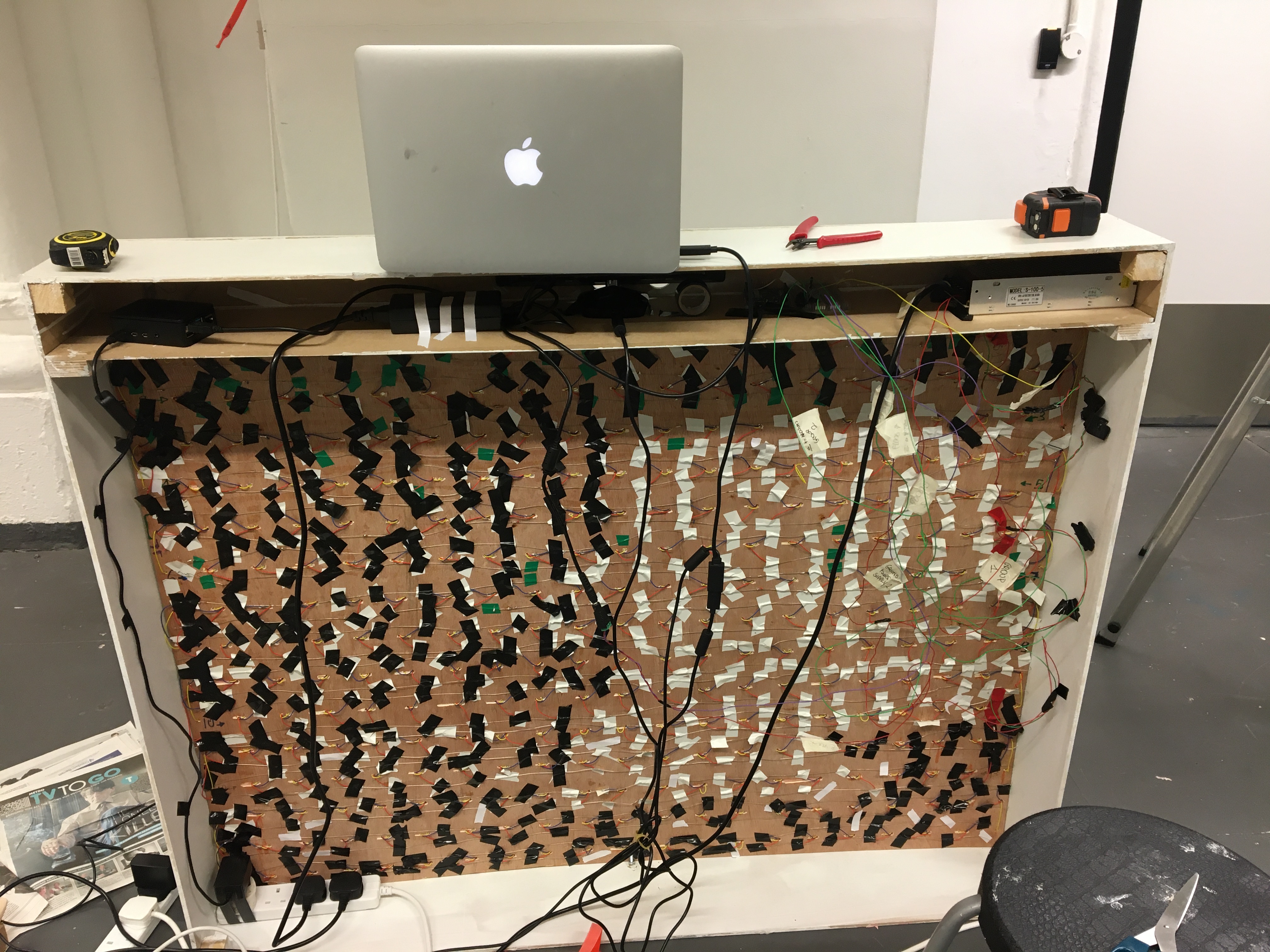

The process of connecting all the lights together took much, much longer than expected. Not because of the laborious and time-consuming nature of the work, but because of the multiple complications that have occurred. Despite the fact that a strip of 300 LEDs was working perfectly fine on a power supply of 5V 20A, it looked like a multitude of factors, such as the extra wires and connections, as well as the quality of the LEDs and the soldering, caused a massive drop of voltage. These difficulties, and the unpredictability of physical computing, have burst the system multiple times, burning a lot of pixels and causing me to start all over again for four times. Eventually, thanks to a lot of help by fellow students, I have spotted the issue, and decided to use three different 5V power sources, that would supply 5 rows (100 LEDs) each, preserving a consistent flow of power.

Making-of.

Structure

The structure was manually built in MDF. The size of the LEDs panel is 122x918mm, keeping the aspect ratio of 1,3. I have then built a bigger frame structure, which allowed me to create a shelf in which I could insert and hide Kinect, Arduino, the three power supplies and RaspberryPi. I have organised the 300 photos I have collected from Google Street View on a grid in InDesign and printed them on a big clear acetate sheet, which I have manually layered over a sheet of lightbox acetate. In this way, the images would be perfectly clear and yet still let the light shine through.

FURTHER DEVELOPMENT AND SELF-EVALUATION

Overall, I am quite satisfied with the project. It has truly pushed me out of my comfort zone, from the amount of electronics work involved, to the DYI work, to even just understanding how to use a RaspberryPi. I had moments were I truly struggled with physical computing, but I am glad that I persevered in my attempts to fix it.

I do believe that the project could be extensively improved. Originally, I wanted it to be larger and more invasive, but the final result was definitely more feasible given the circumstances in terms of space, materials and support. The current structure is quite bulky, and I believe I could make the frame structure neater and smaller, possibly using acrylic instead of MDF for a more compact look; I’d like to hide the camera a bit better, or use motion sensors, similarly to Daniel Rozin. I could also improve the interaction by playing more with the ways in which the lights turn on, creating a trail effect by fading them.

Research and conceptual exploration are the steps I value the most within my practice, critically looking at the ways in which we integrate technology in our lives, and I did learn a lot in the last few months. Although this project does not offer one simple answer or point of view, it aims to open discussions and raise awareness. Throughout the exhibition, I have indeed truly appreciated conversing with visitors, acquiring different visions, as well as simply observing their interaction with the piece: a playful experience at the moment of the first interaction with the lights, realising their movement is what is activating the piece, and finally getting closer to the images, spending more time observing what they are and what the piece wants to say.

REFERENCES

Cirio, P. (2012) Street Ghosts. Available at: https://www.paolocirio.net/press/texts/text_streetghosts.php

Haraway, D. (1988) 'Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’. Feminist Studies. Vol.14, 3.

Henner, M. (2013). No Man’s Land. Available at: https://mishkahenner.com/No-Man-s-Land

Ingraham, C. & Rowland, A. (2017). How Google Street View Became Fertile Ground for Artists. Available at: https://theconversation.com/how-google-street-view-became-fertile-ground-for-artists-77845

Kai Lab (2020). Sinusoidal Noise. Available at: https://kailaboratory.com/sinusoidal-noise

MacDonald, Calum (2007). "Google's Street View site raises alarm over privacy". The Herald.

McNeil, J. (2015) "An interview with a Google Street View Driver" . Available at: https://medium.com/message/an-interview-with-a-google-street-view-driver-240d067a7545

Rickard, D (2010). A New American Picture . Available at: https://dougrickard.com/a-new-american-picture/

Rozin, D. Interactive Art. Available at : http://www.smoothware.com/danny/

Strom, T 2011, ‘Space, Cyberspace and Interface: The Trouble with Google Maps’, Media and Culture Journal, vol. 14, no. 3. viewed 22 March 2015,

Wolf, M. (2010) A Series of Unfortunate Events. Available at: http://photomichaelwolf.com/#asoue/1