TO FORGET HOW TO THINK.

Luke Dash

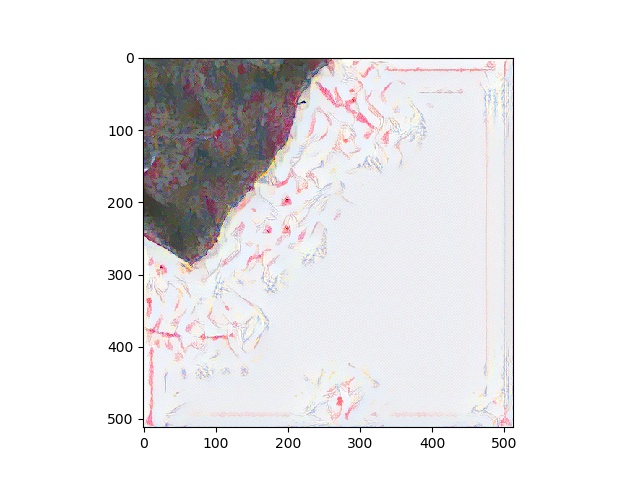

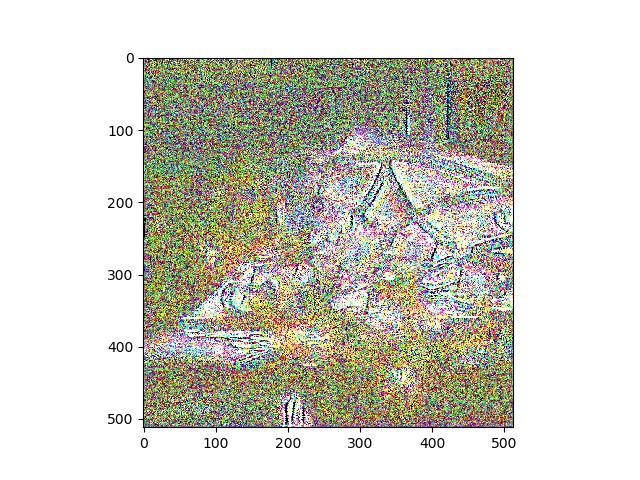

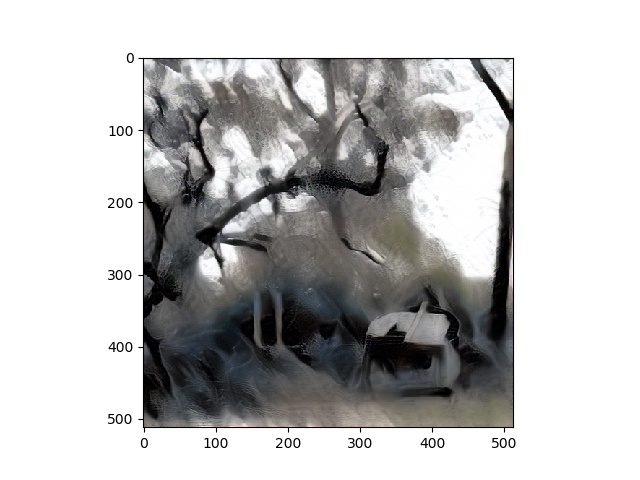

In this paper, I establish an automated, reflective painting practice. By implementing a simple iterative program which uses Style Transfer (Jacq, 2019) procedurally on my drawing portfolio, the intent is to begin to perceive and discuss which aspects of my creative process are abstracted away from me when dealing with automation. More generally, I consider this act a catalyst for understanding how emerging technology in a creative domain might begin to change how we think. As my machine continues to silently paint new pieces of art (or as I am absent and dislocated from the machine, and trust that this process is still ongoing): questions are continually raised. Where does the creative individual now need to be corporeally? Should we be loyal to the process and stand guard to adjust and validate it? Or should we embrace the potential to displace ourselves from the physical element of the process and seek new experiences to inform the intention behind the next iterations of our code? Which kinds of new provocations become available to us? What kind of thinking does the emerging ubiquity of software automation afford us? So many questions emerge, in fact, that choosing one this soon would be counterproductive. Instead, here I focus on asking how to grapple with this overwhelming landscape.

My focus is theoretical here. My initial intent to learn about software could perhaps have been considered adversarial. Honestly, I think the appeal in software and tech from my perspective (a tired creative graduate) has to have involved a fear of being left behind. I think there is a need to compete with a “real, working world” is implicit in that intent to creatively engage with software. However, as I continued with finding simple methods for expansion of my drawing practice through software, the experience began to raise flags for me conceptually. The tangible goal I had in mind was to work towards understanding what we popularly refer to as AI. In particular, the use of neural networks for generative processes was something I was keen to interface with my approach to drawing. This interest is borne of a desire to make a process based drawing practice more socially provocative. Software, automation, and social media are all the mediums which most directly embody our zeitgeist (McLuhan, 2008), and its problematization, after all.

The recent work of Pierre Huyghe is surely an interesting provocation. In Uumvelt, (Serpentine Galleries, 2019) the space we get to walk through brings an awful lot of uncomfortable ideas to the surface. Large bugs bumping into my face while screens silently turn over insipid, textural and vague neural network generated images. I would be lying if I were to downplay this installations influence on my practice. But no one passing me in the hours that I stood there could agree on what was happening. Someone passed saying that the screens were absorbing the impacts of the flies, and that that was in turn re-training the neural network in real time. Someone else said that the network must have been aware of the spectators gaze. The material about the exhibition up-sells the process, asserting that the presence of flies and changes to the closed environment produces a ‘feedback loop’. Very exciting. But from the galleries material, its main cultural point of interest is a bizarre fetishized eschewal of the discussion around the word agency. With that, is this a constructive provocation, which encourages discussion surrounding agency? Or is it an exacerbation of our widespread ignorance surrounding the topic? I find the latter to be the most useful interpretation of the work.

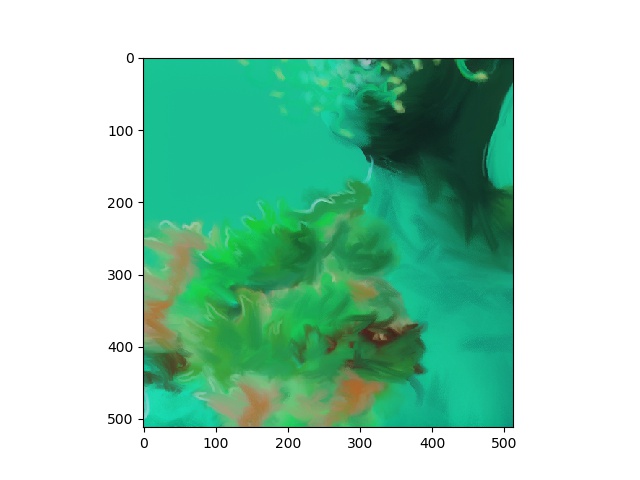

Other artists working with AI force less conceptual narrative into the presentation of their art. Memo Atkens Learning To See is a hugely inspiring example of art made using neural networks. We see a program rendering beautiful paintings from a live webcam feed. Crude sketches and every day objects become reminiscent of Turner paintings and the like instantaneously and continuously.

The reflection he writes on the piece is also a large influence on my thinking for this paper. He posits that we can consider Google (the source of his training data) as the overseer of our collective consciousness. (Atken, 2019) This idea of the transference of a cultural consciousness into a container (the cloud) which presents itself to us as technology is pretty riveting, and I think it represents the subtext for most contemporary discussion of both art and technology today. But here’s the question this concept brings to me:

With all this rhetoric surrounding replacement, prosthetics, transference, are we so swept away with where our thoughts are going; that we are beginning to forget that we still have not agreed on how to think?

I would love to indulge a detour into Maurice Merleau-Pontys Phenomenology of Perception at this point, but this avenue lies just outside the scope of this essay. Although, I admit that I am splitting hairs here, as I will note a different (only more poignant) ‘phenomenology of perception’ later. (Sartre, 2010) Still, though this is reductive: briefly pause and consider where perception begins and ends when the subject is adjacent to a prosthetic (“le bâton de l’aveugle”, their macbook)… Because despite the question representing too many conflations to ever handle in this paper, this perhaps messy notion does point neatly to the theoretical domain from which my proposed discussion emerges. (Merleau-Ponty, 2013)

To my mind, regarding technology-based research, the most insightful discussion which is closest to how we think in relation to emergent technology comes from Human-Machine Reconfigurations by Lucy Suchman. Particularly, since we are speaking experientially from an arts perspective, the chapter: The Human-Like Machine as a Fetishized Object. Here, the problems surrounding the power of our assumptions and misinterpretations of machines which mimic our behavior, or indeed our work, are discussed. (Suchman, 2009) But, like with most contemporary discussion surrounding tech, how these technologies actually affect us cognitively actually falls by the wayside. This is indicative of the research gap that is my focus, which I reiterate in context: is our contemporary figuration of technology, and the discourse therein, making us neglect the problem of how we think?

So here we are. My first step with ‘AI’. To learn the most from it, let’s be pragmatic. We will make it a step back. My methodology for this research is practice based, but I will be using my reflection as landmarks to direct our vision toward older ideas which I believe we should ensure we do not ignore when considering emergent technology, especially in a time where we speak of these technologies as though they are beginning to think. Specifically, Philosophies of perception and of power dynamics take centre stage here.

To look back and invoke older thoughts on thinking (and shoehorn in a recursion joke): To understand newly seized apparatus, one calls on members of the old guard who understood it. (Foucault, 1980)

The python script begins to run. It is much slower it is than I anticipated, so I take my reading to the beach, trusting that the machine will paint while I am gone.

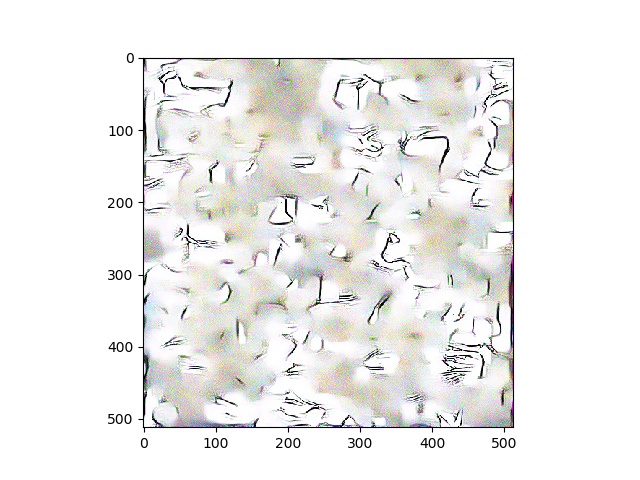

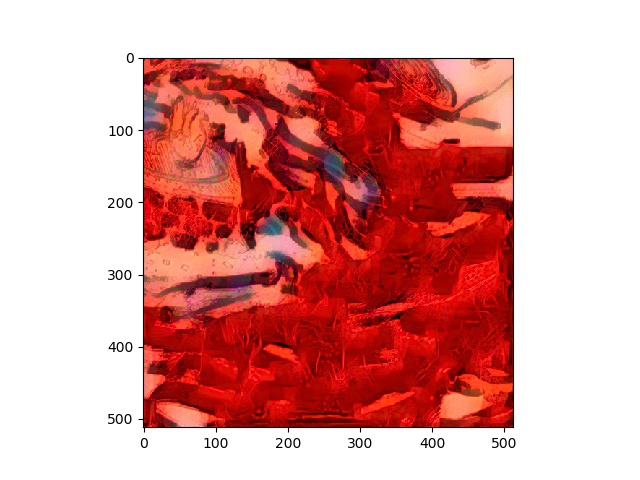

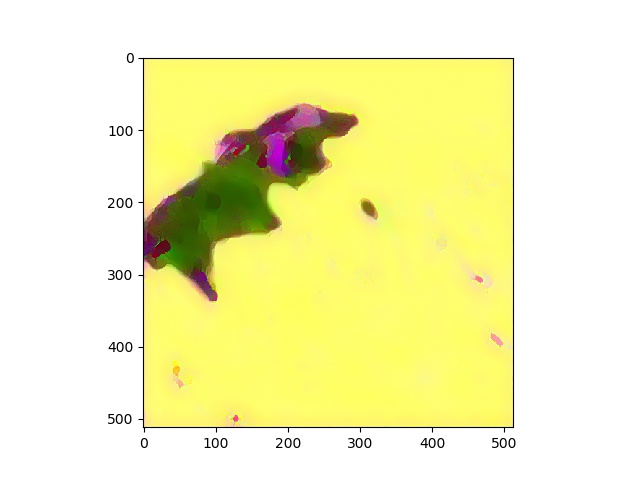

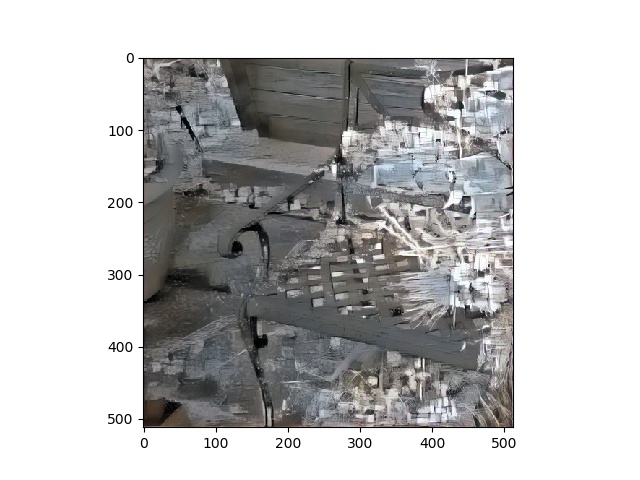

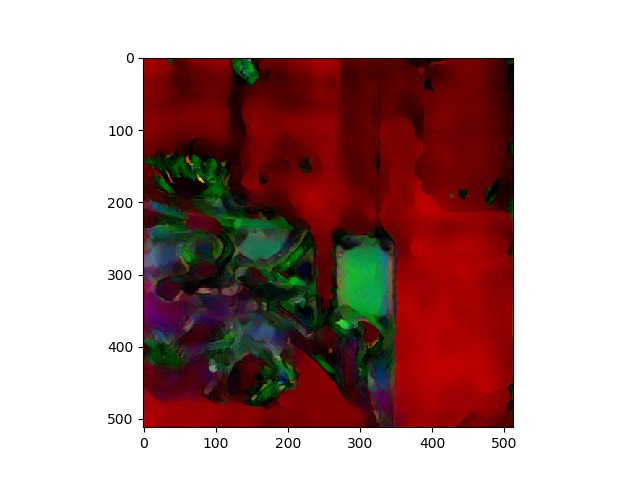

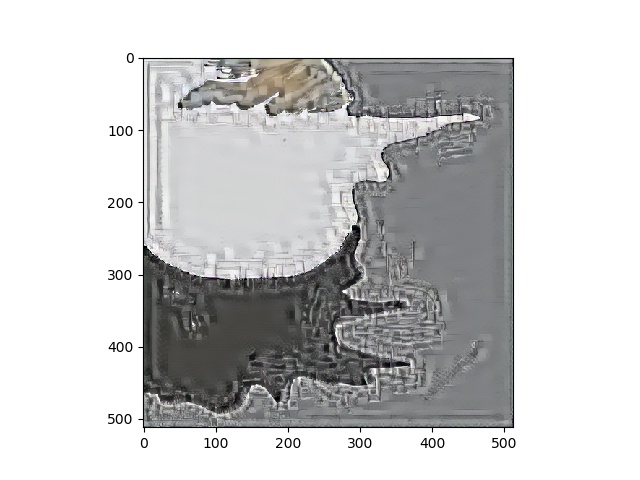

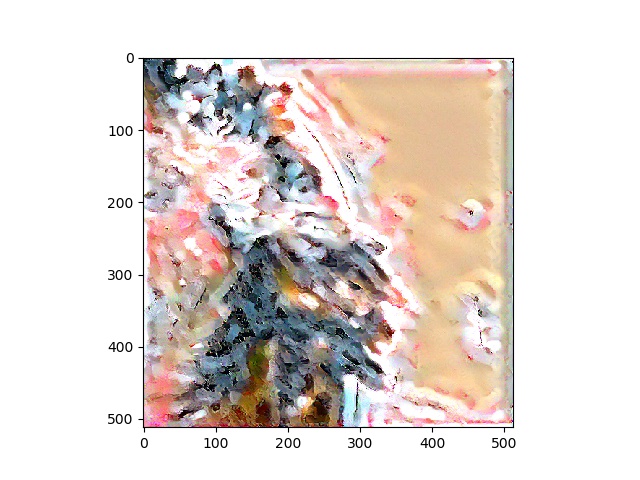

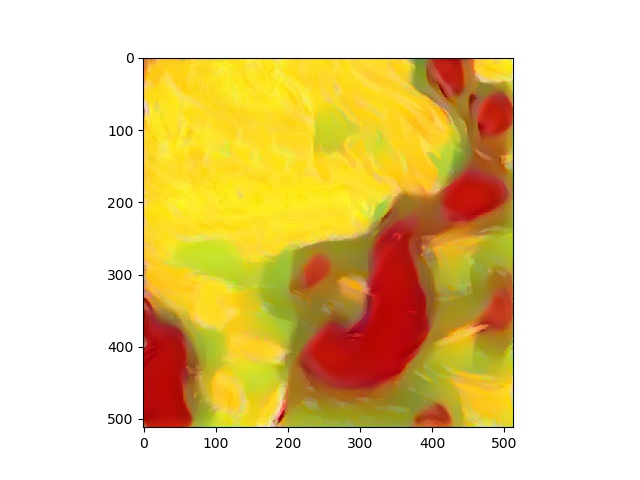

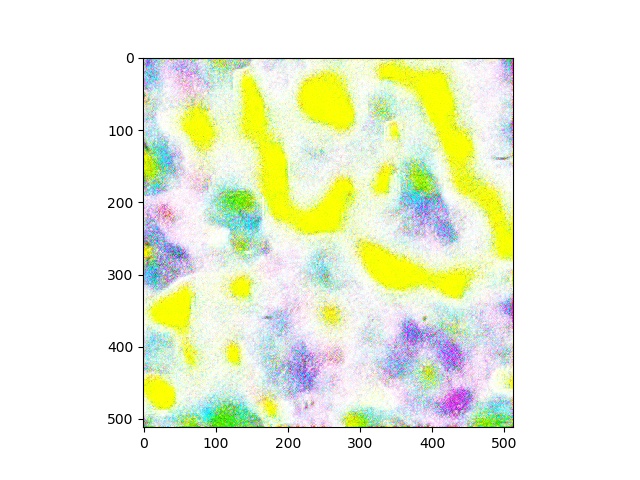

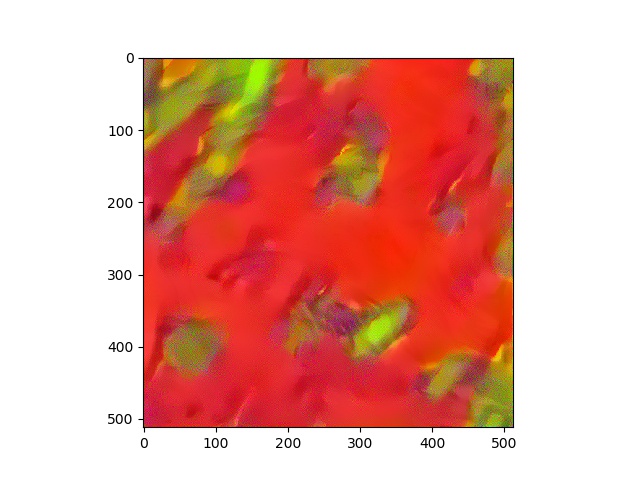

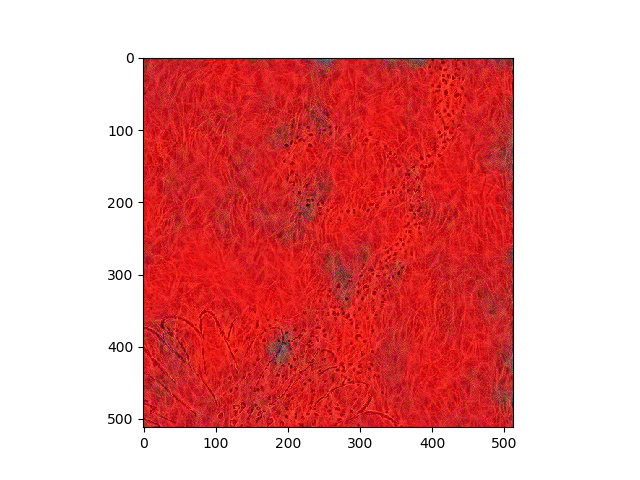

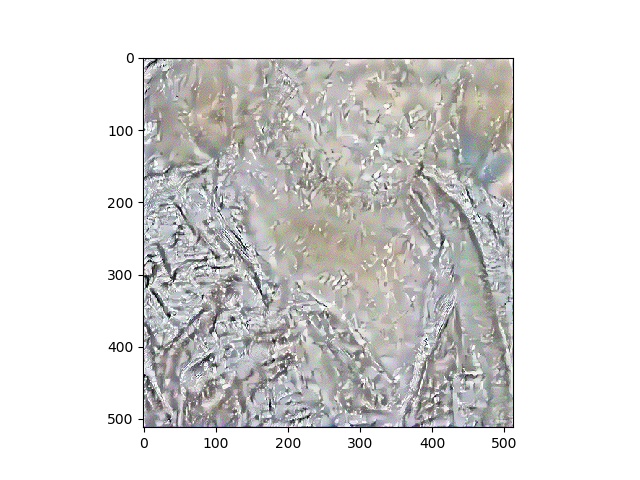

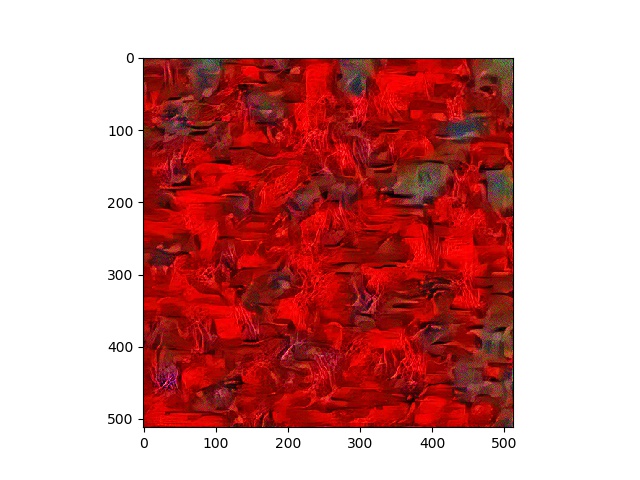

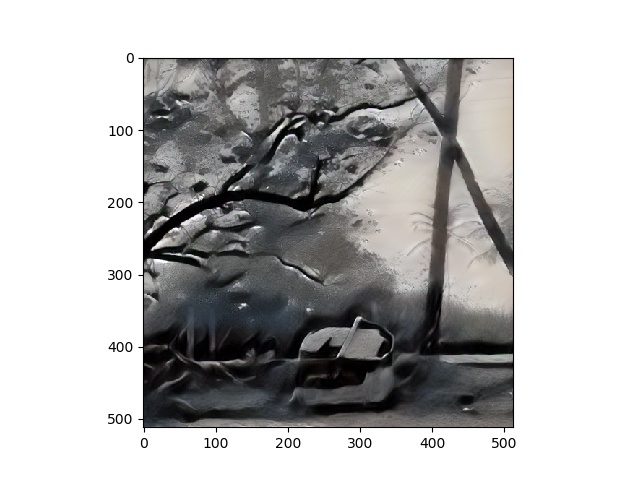

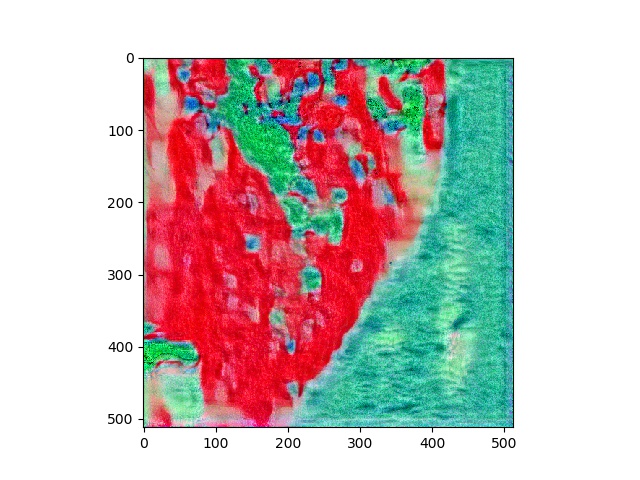

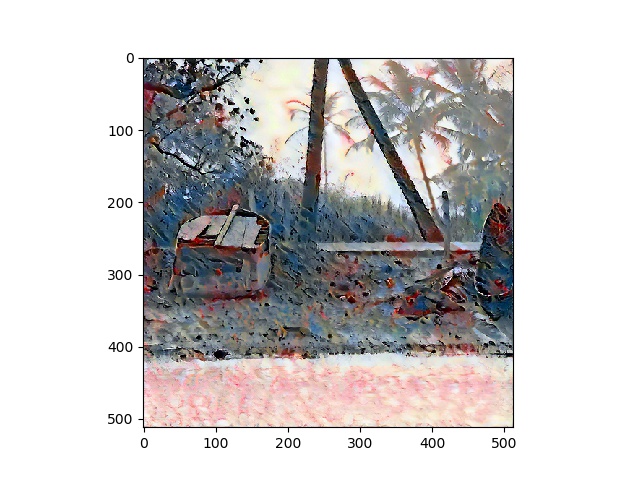

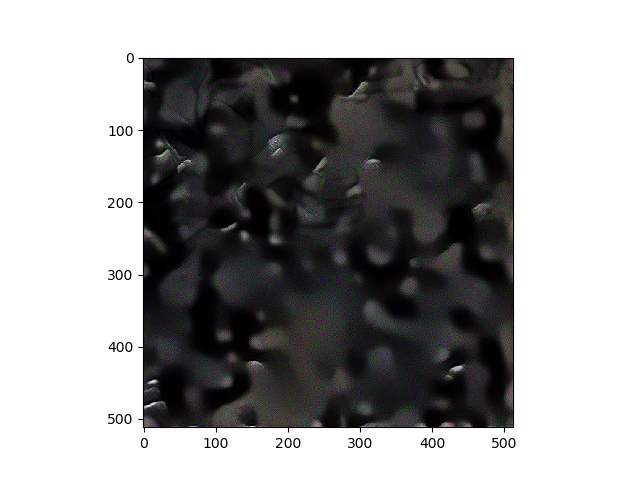

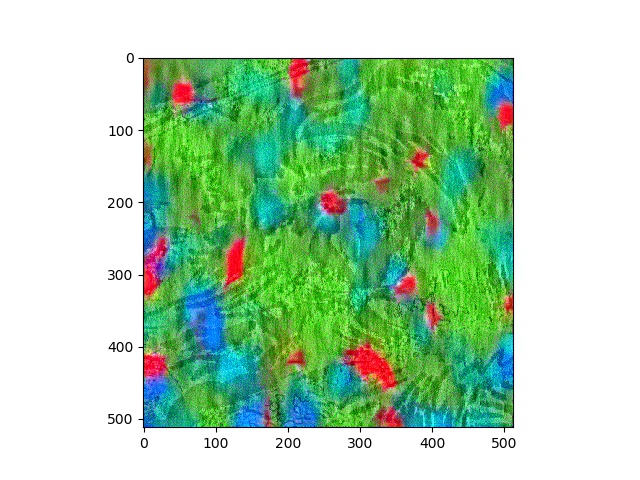

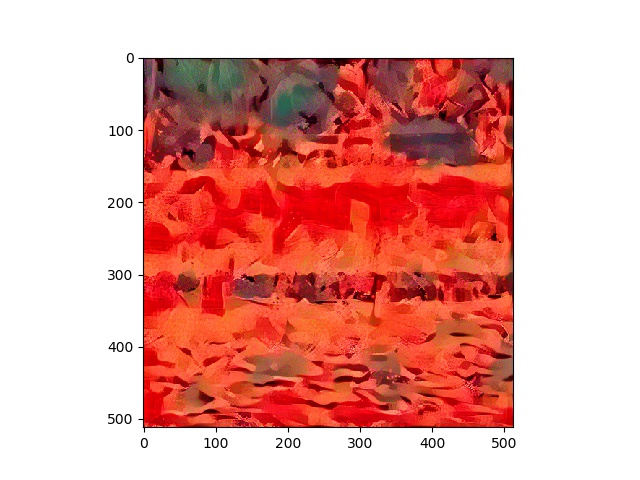

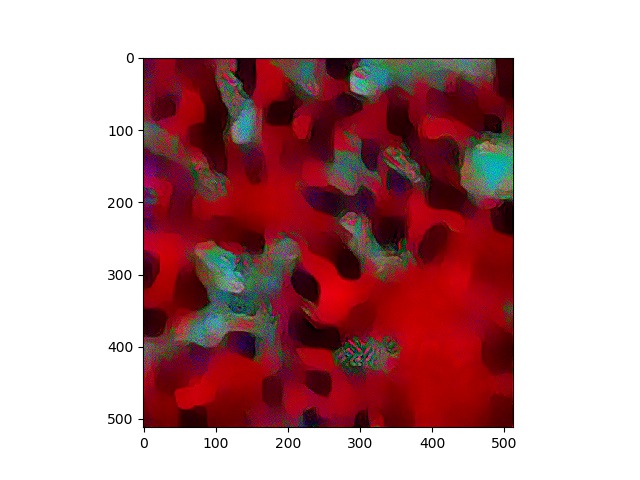

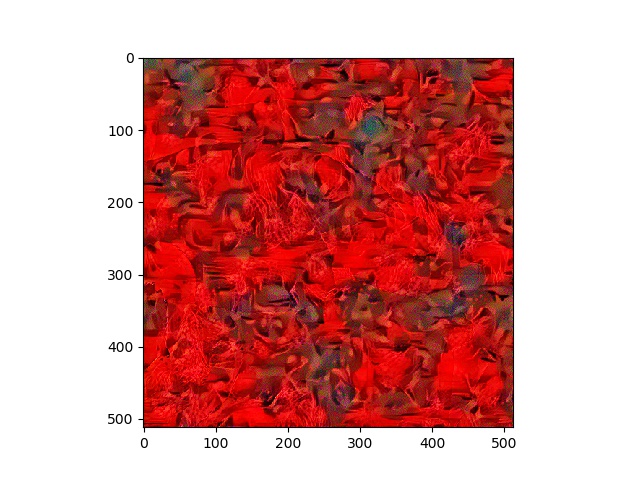

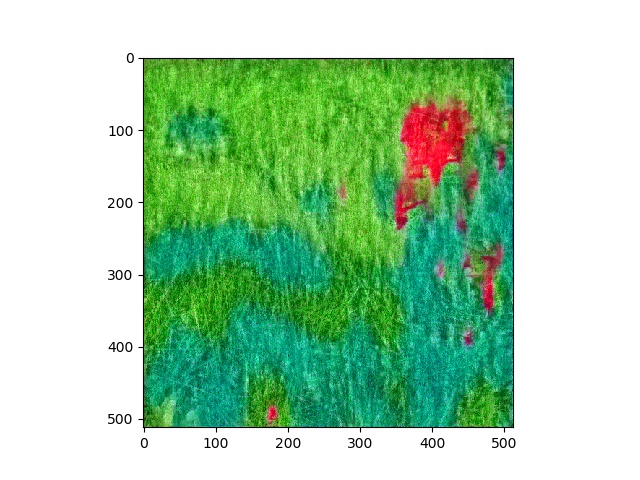

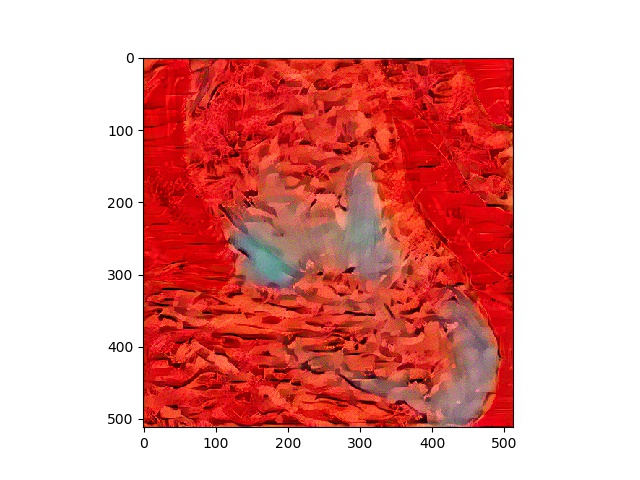

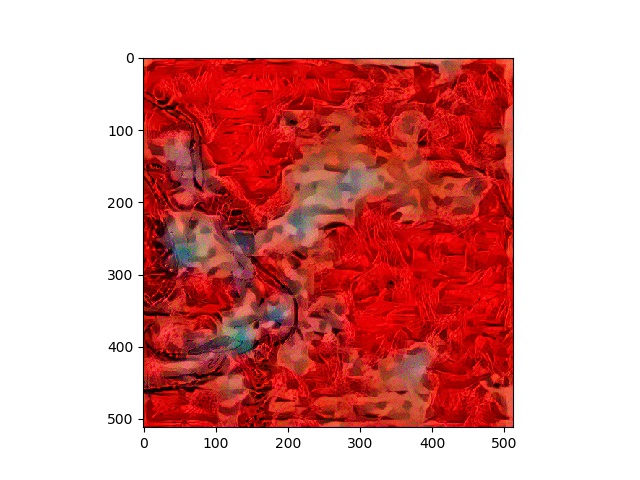

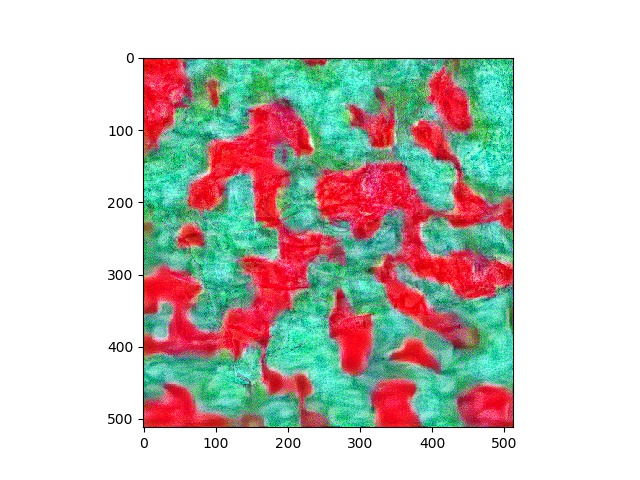

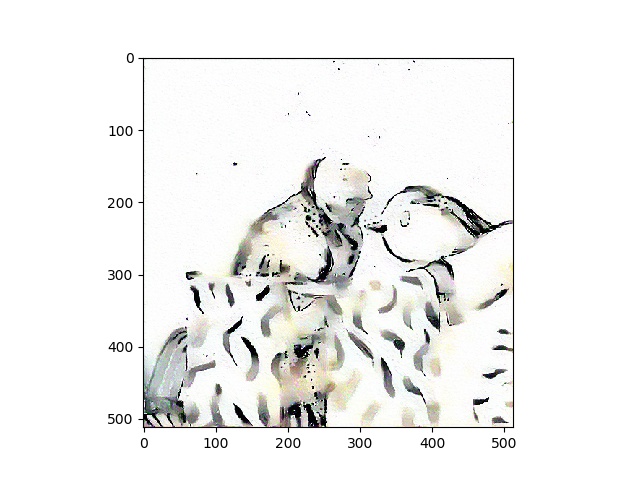

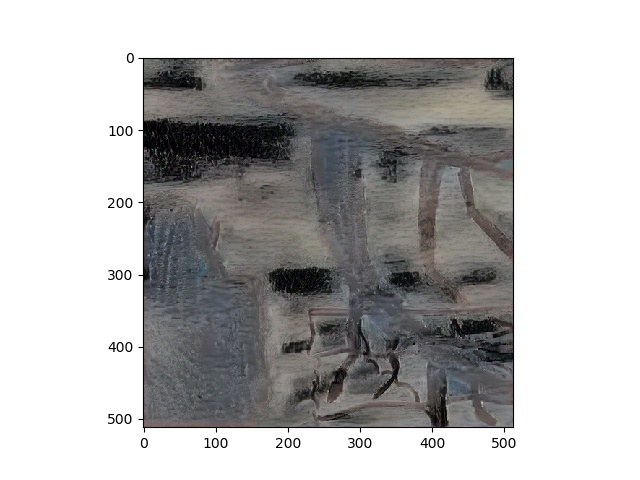

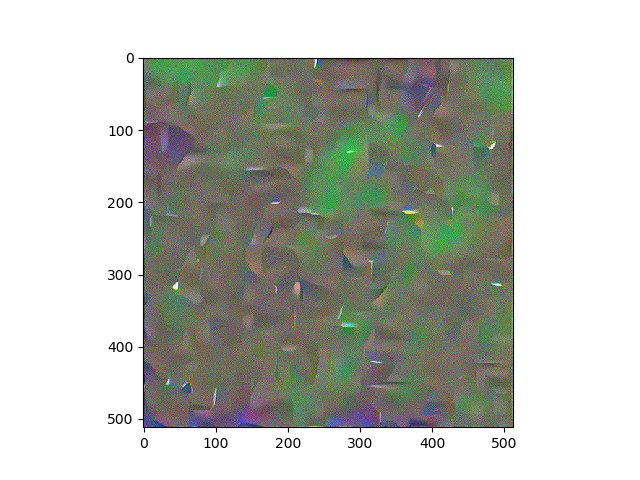

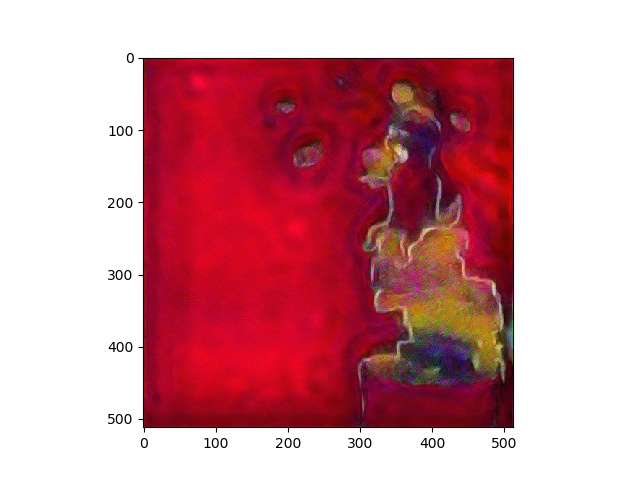

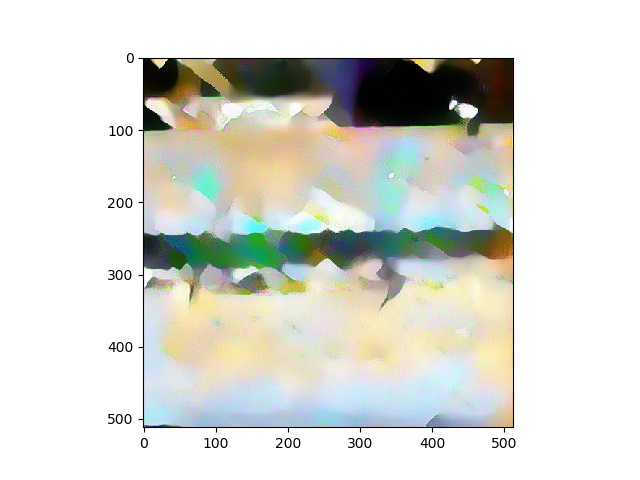

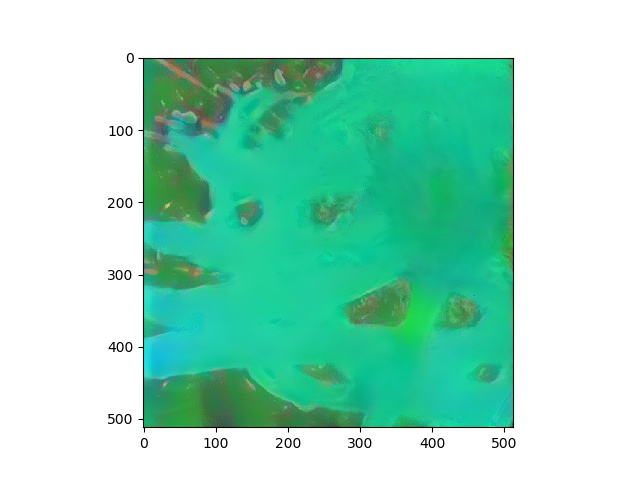

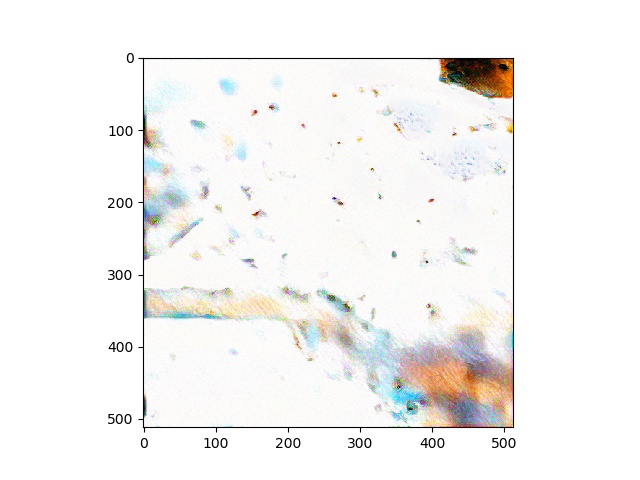

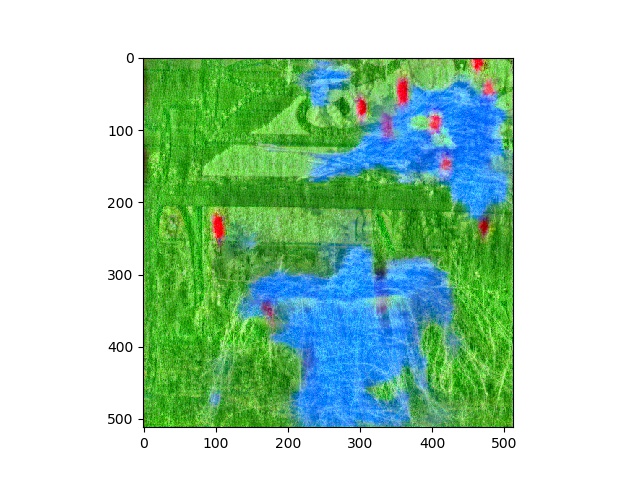

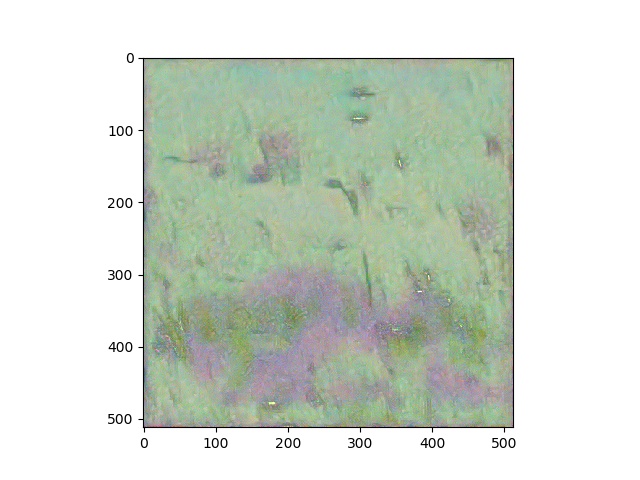

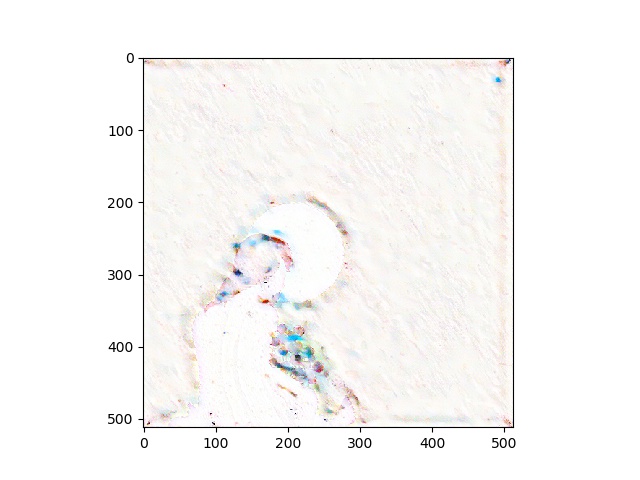

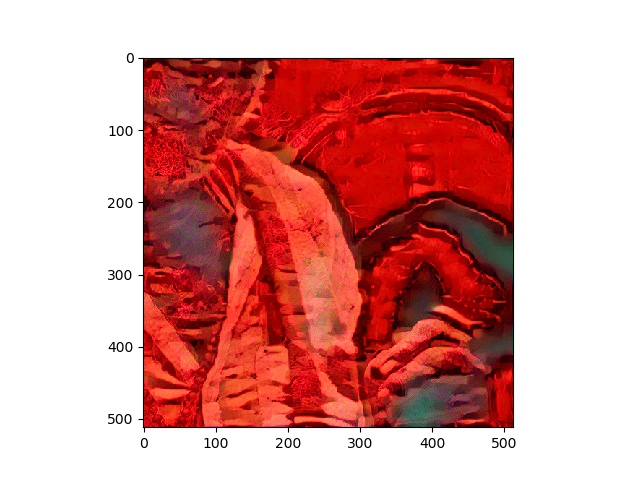

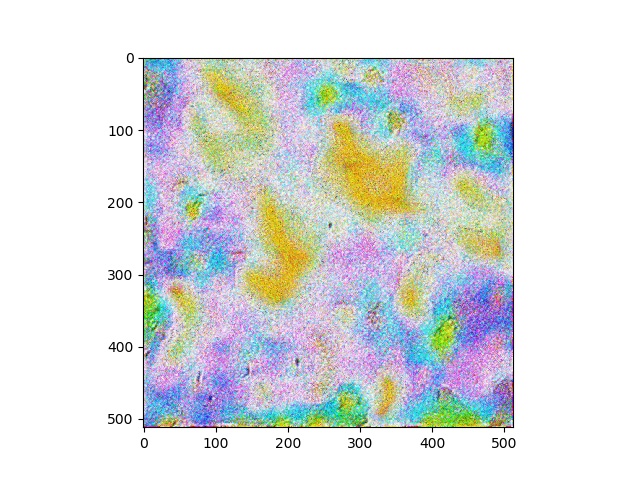

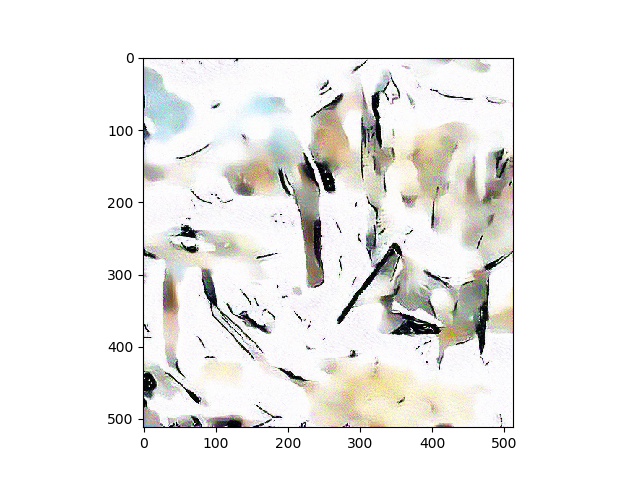

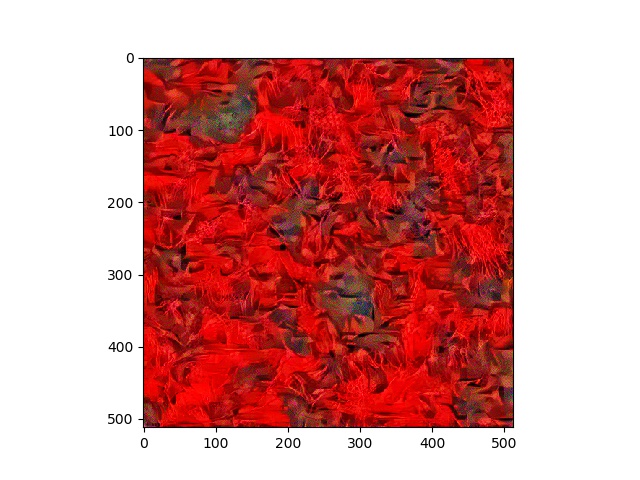

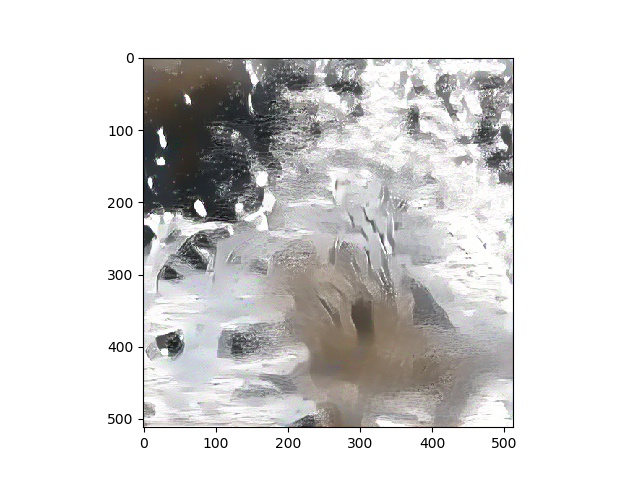

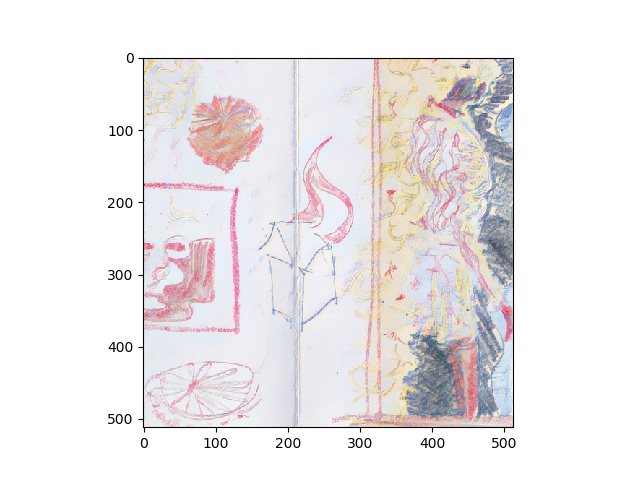

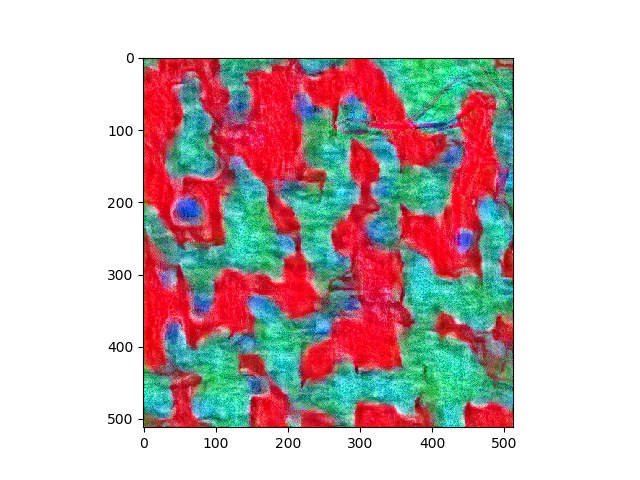

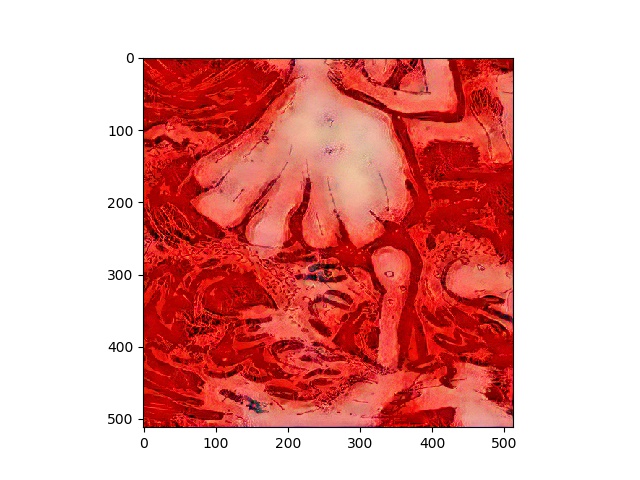

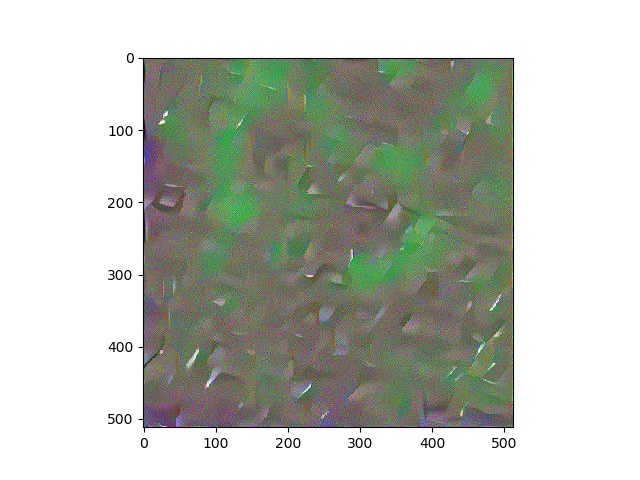

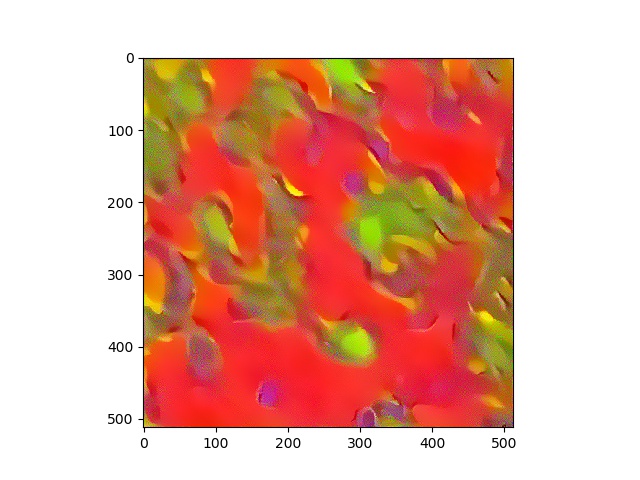

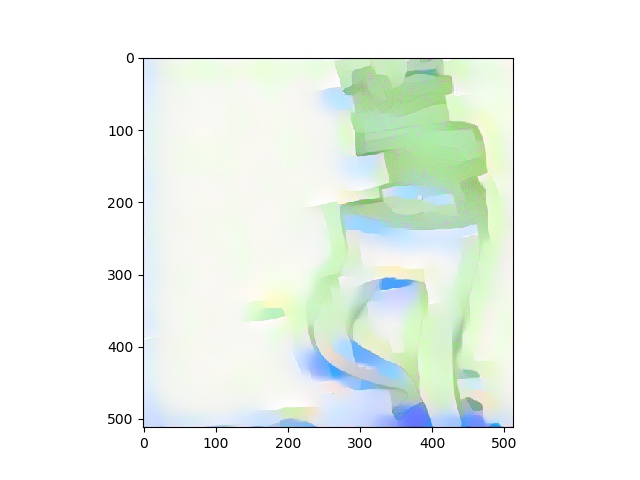

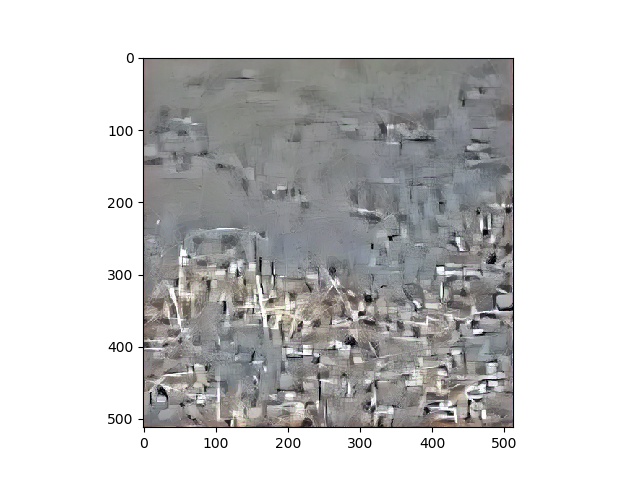

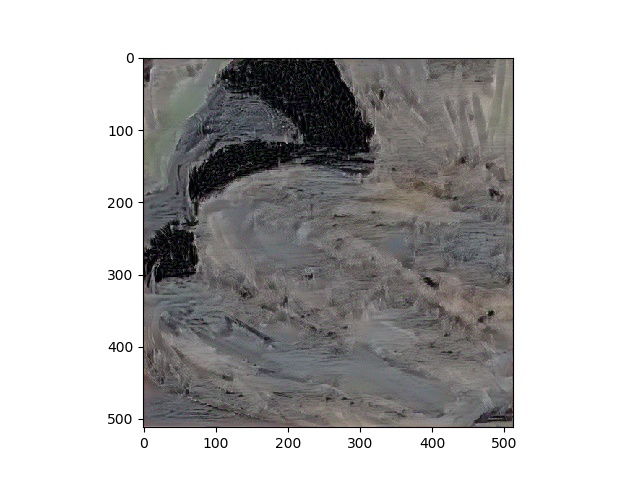

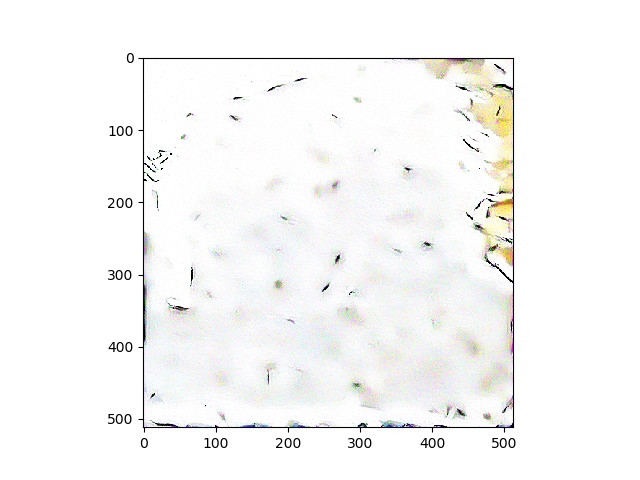

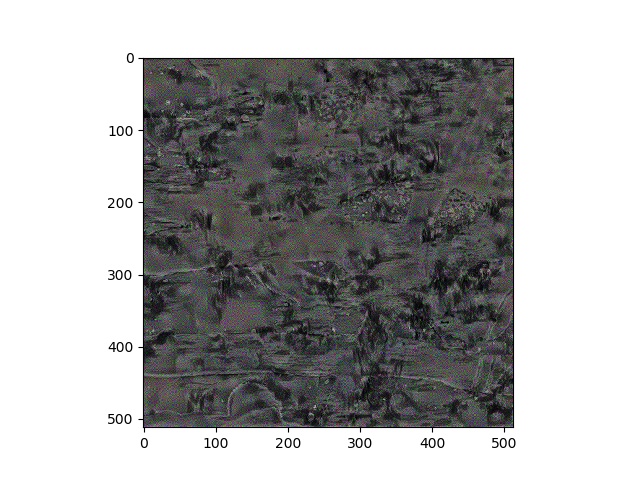

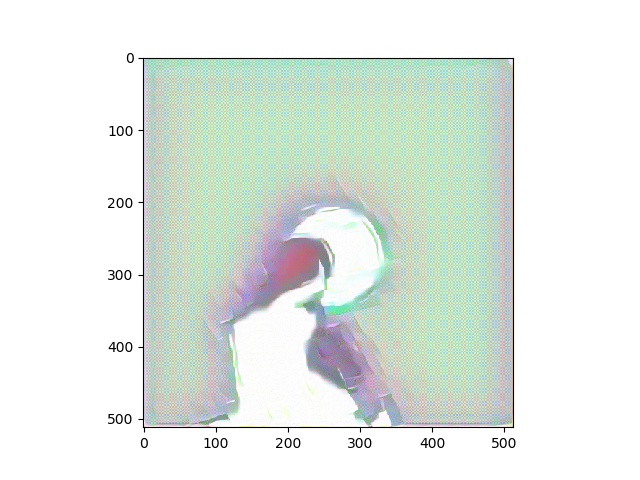

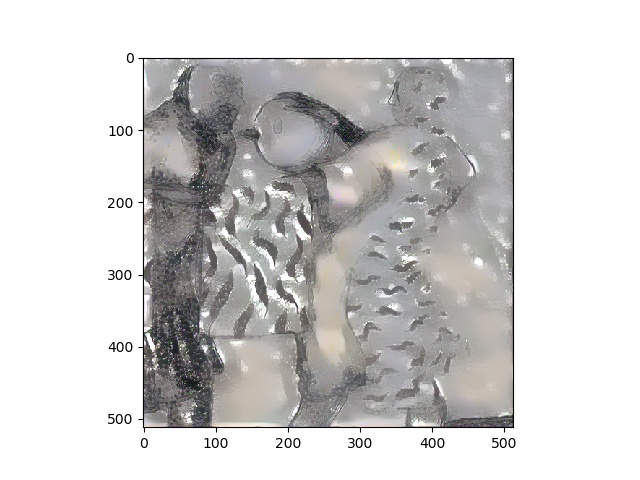

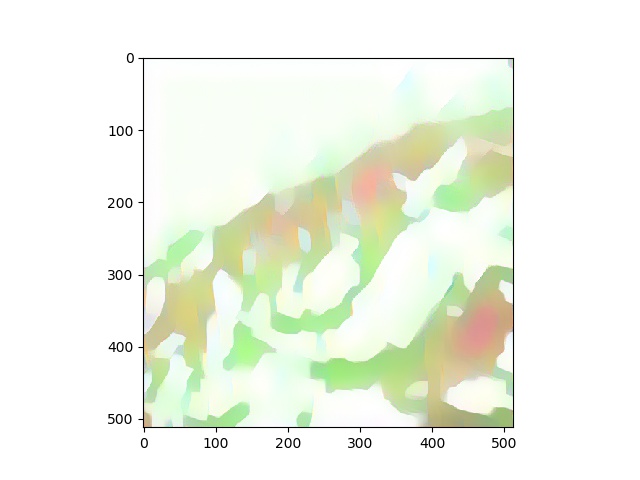

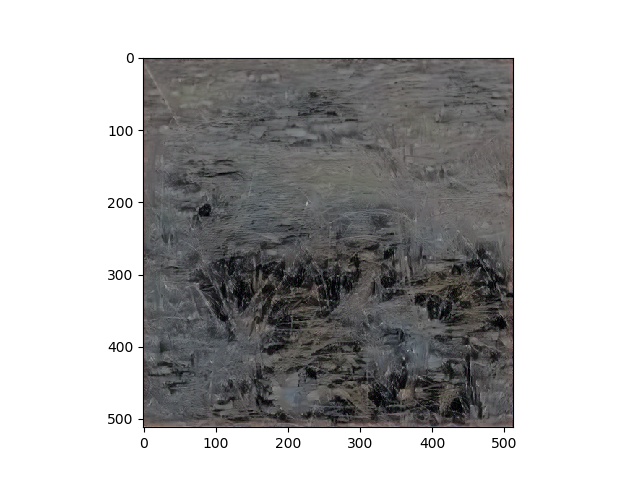

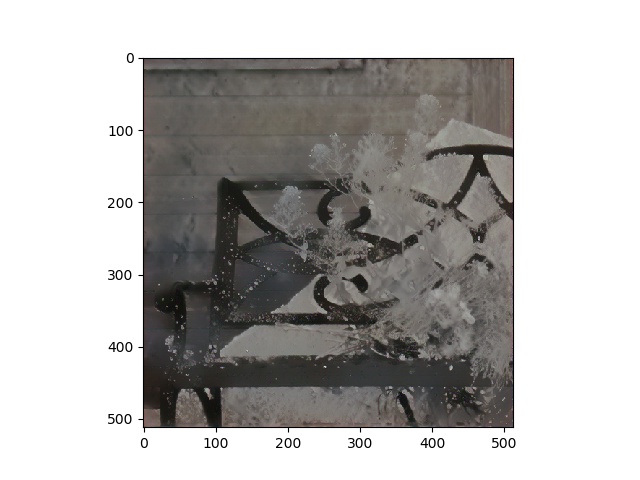

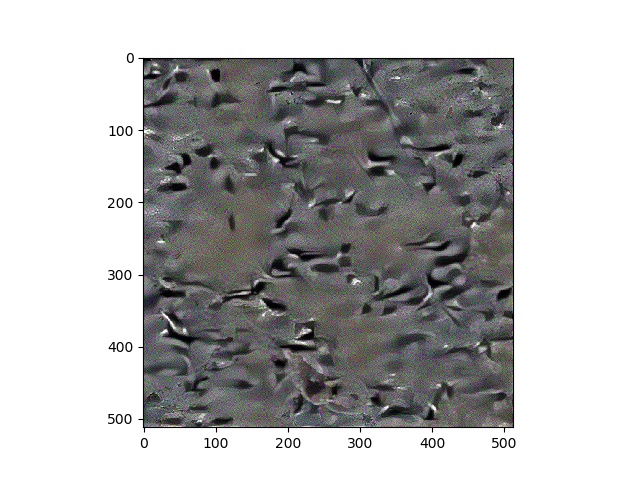

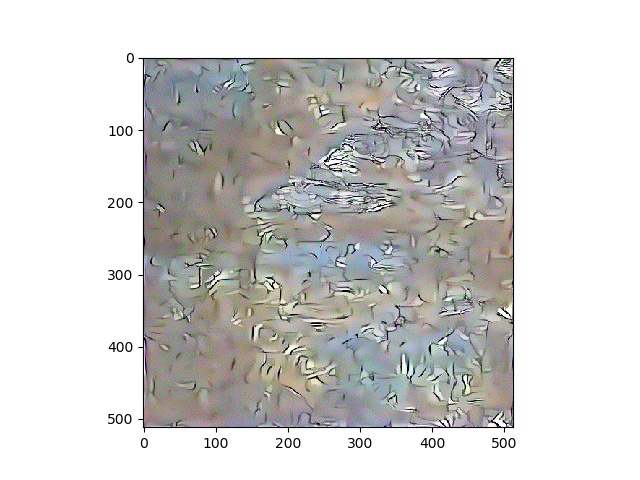

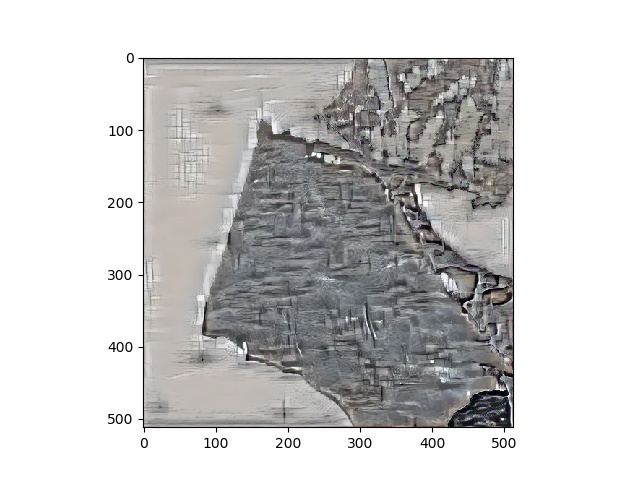

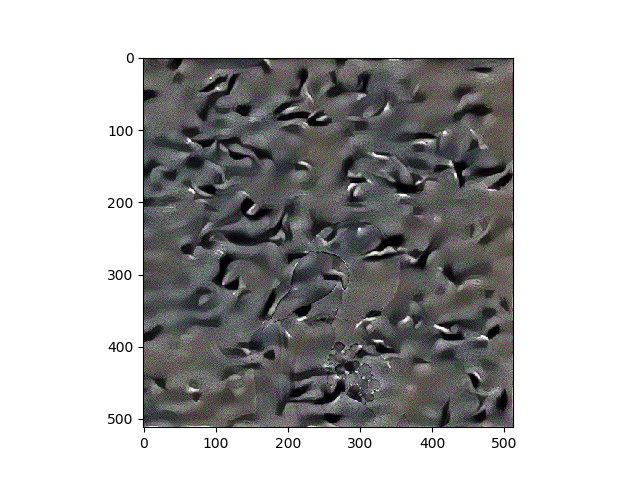

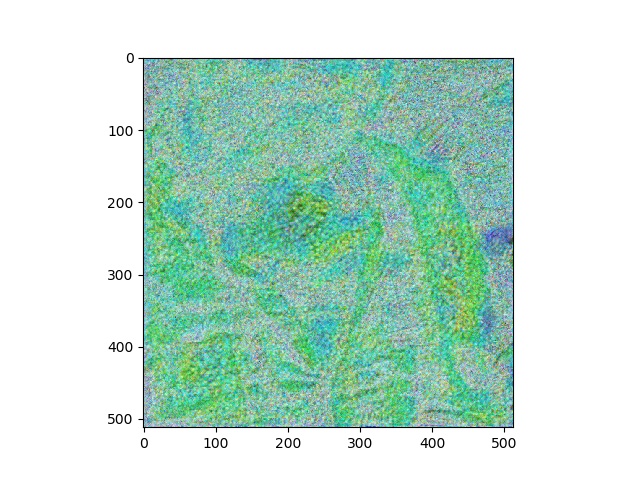

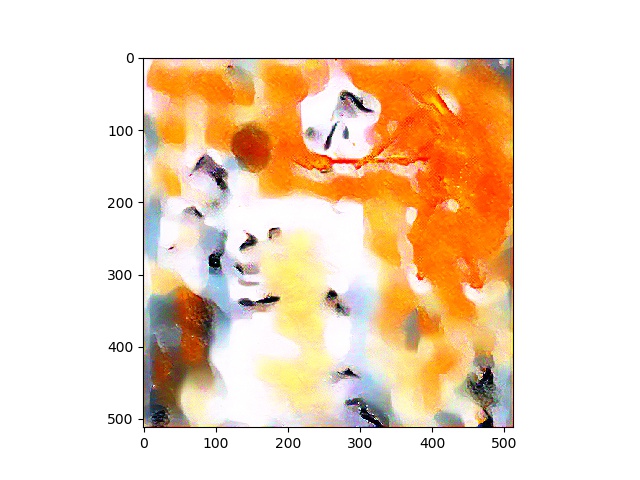

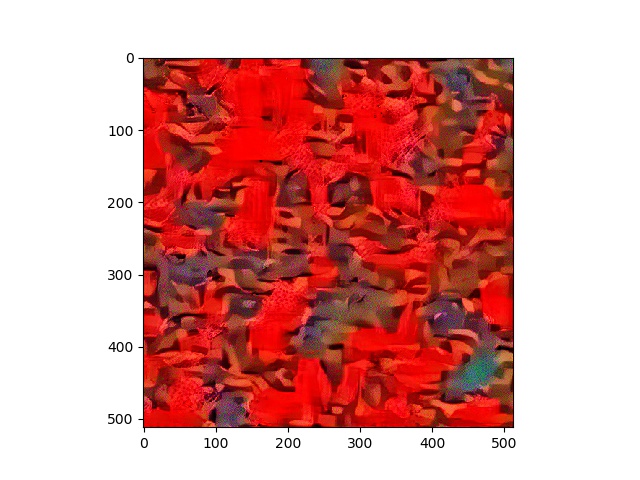

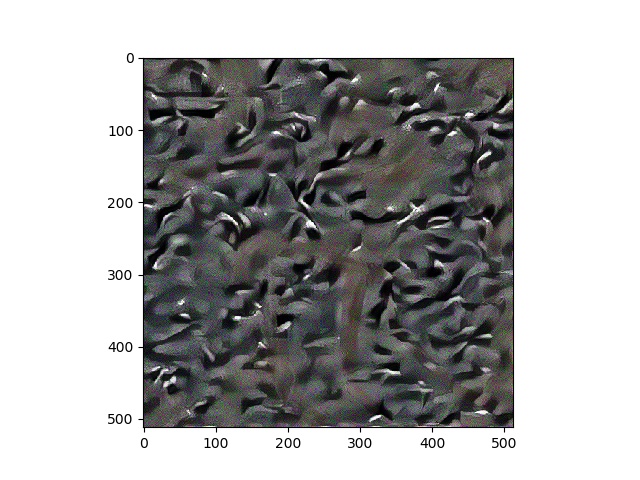

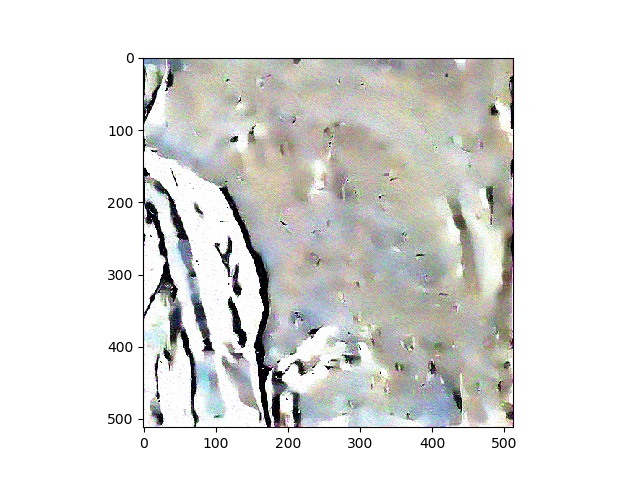

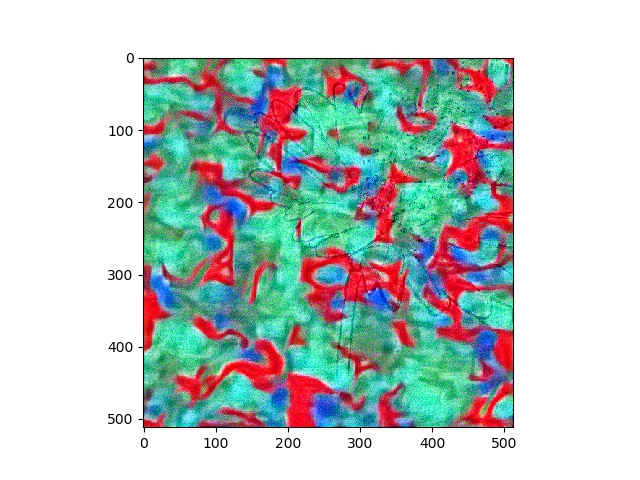

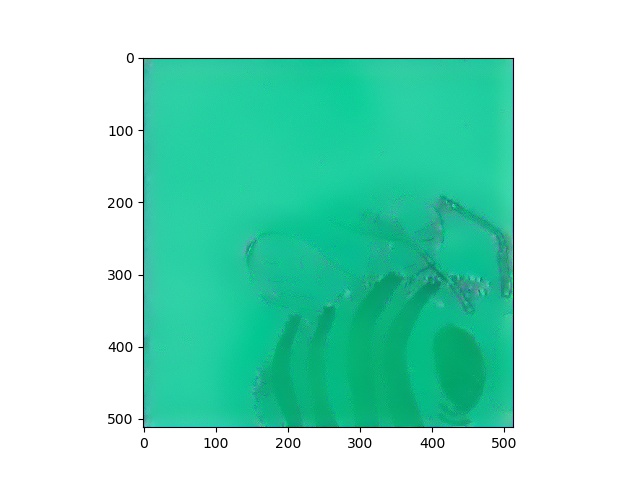

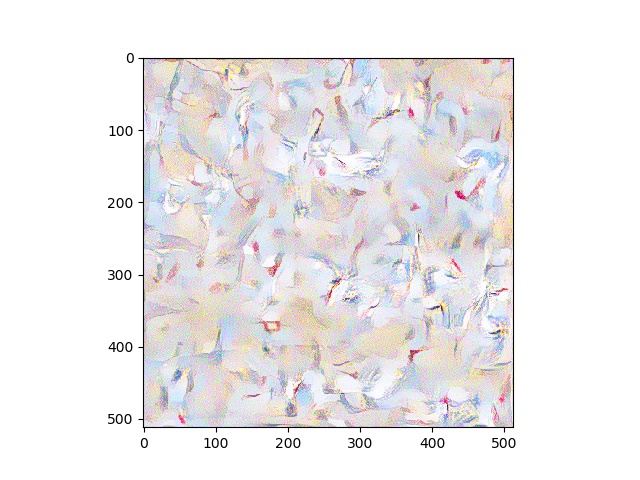

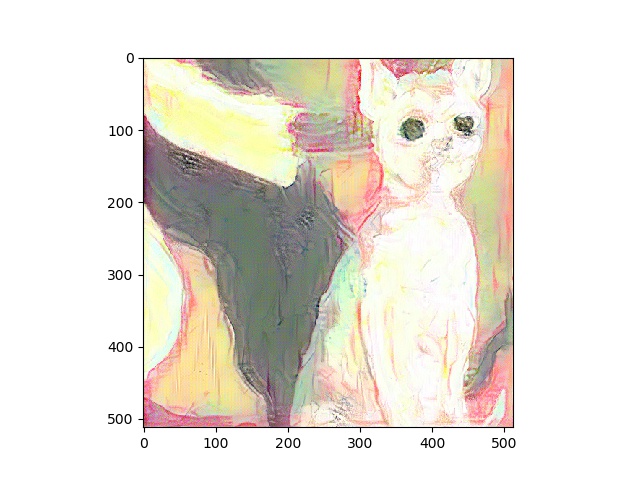

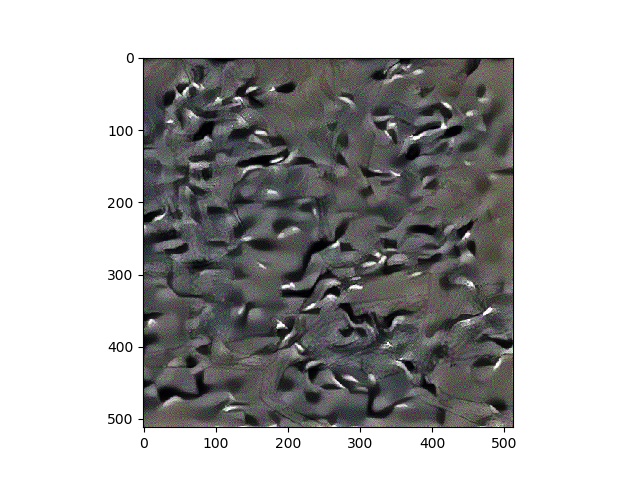

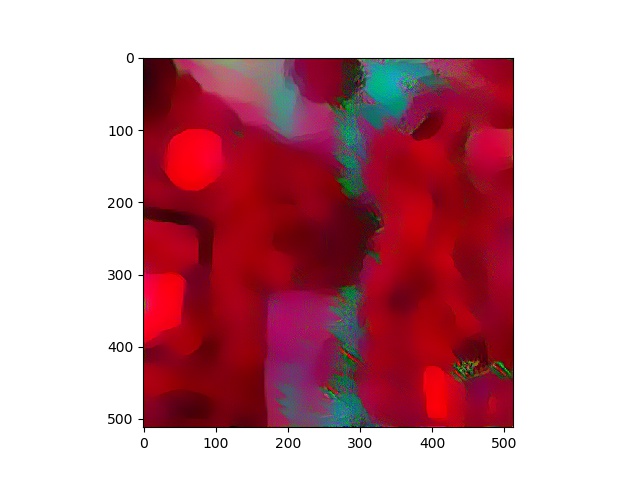

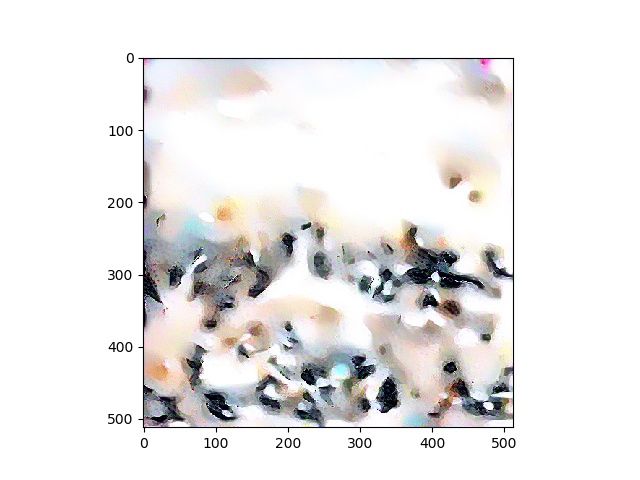

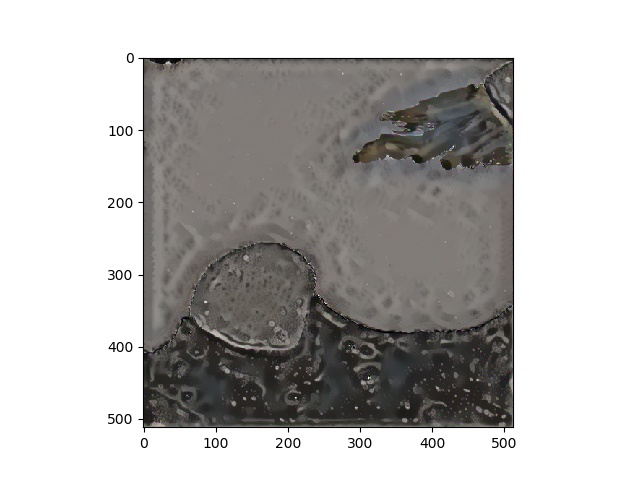

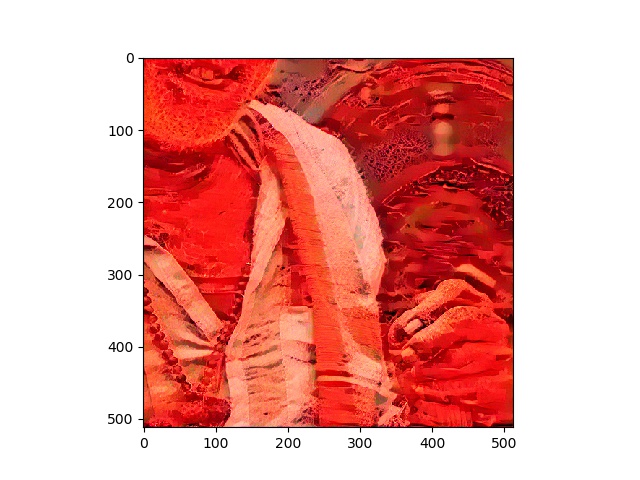

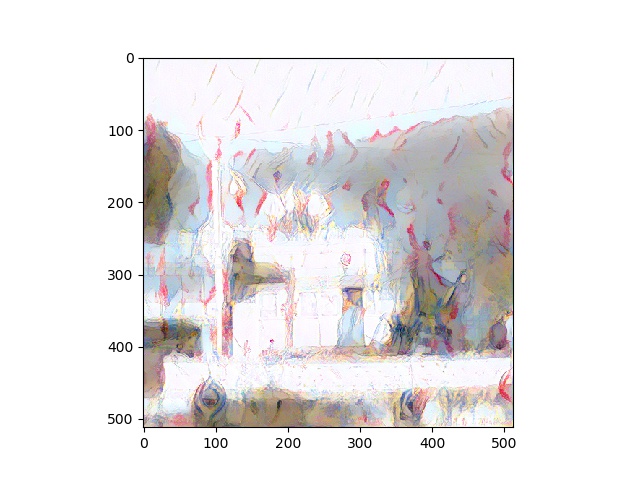

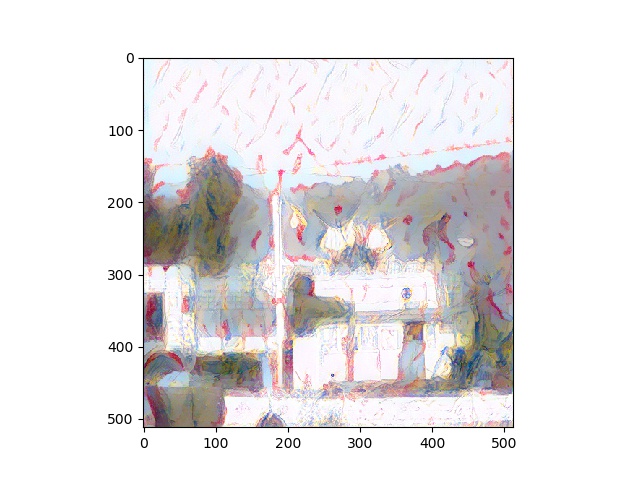

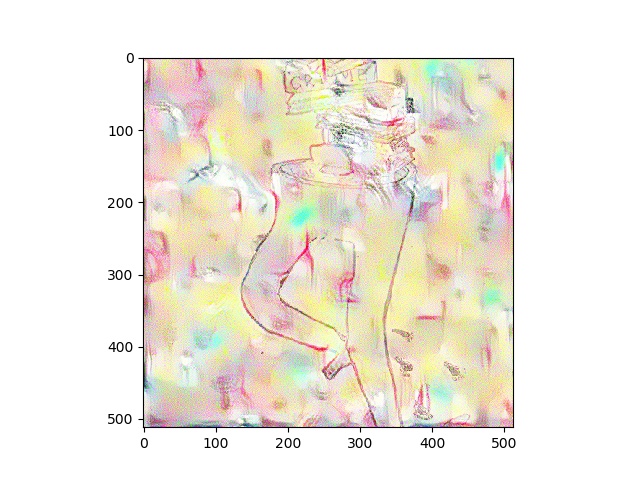

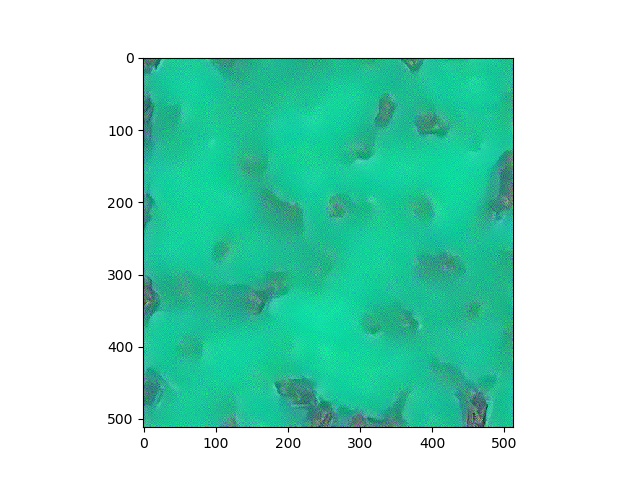

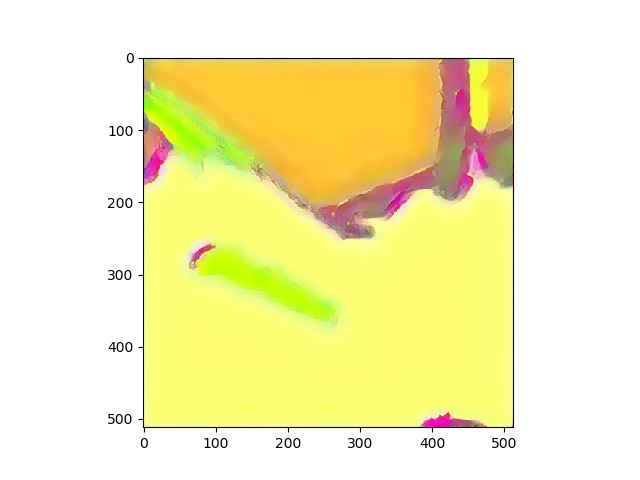

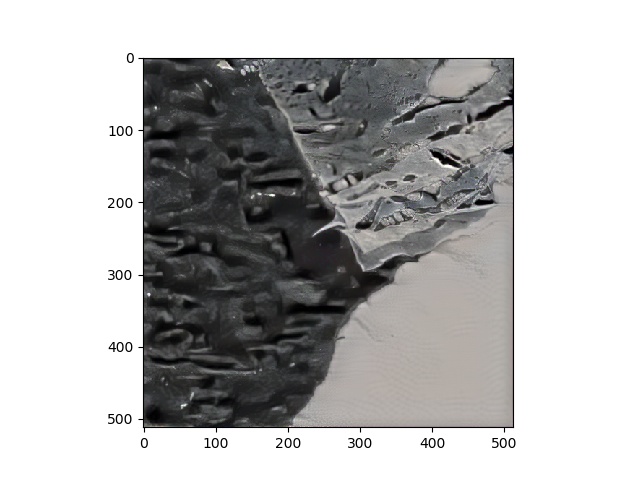

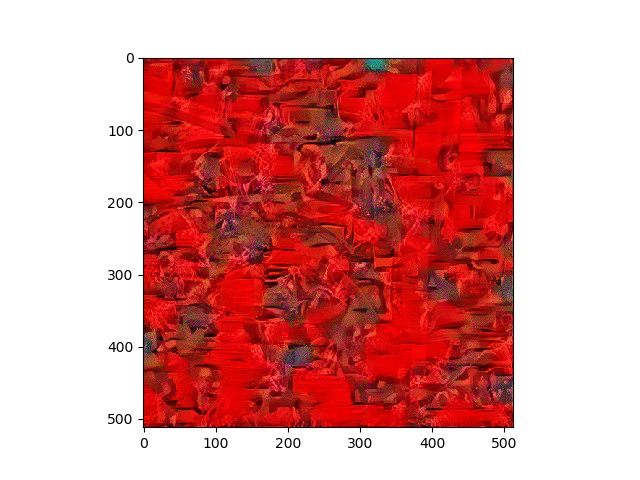

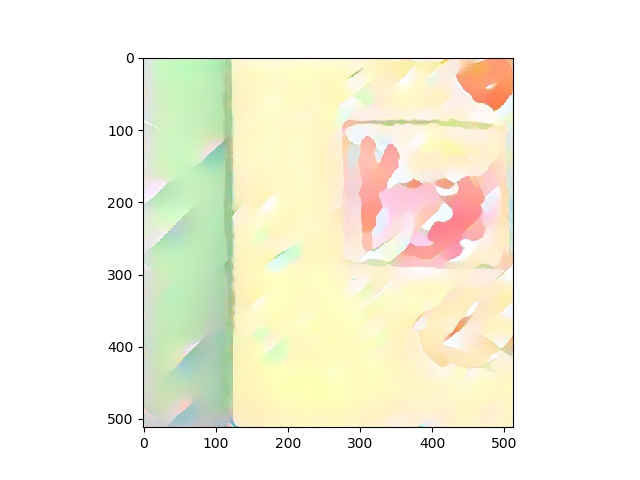

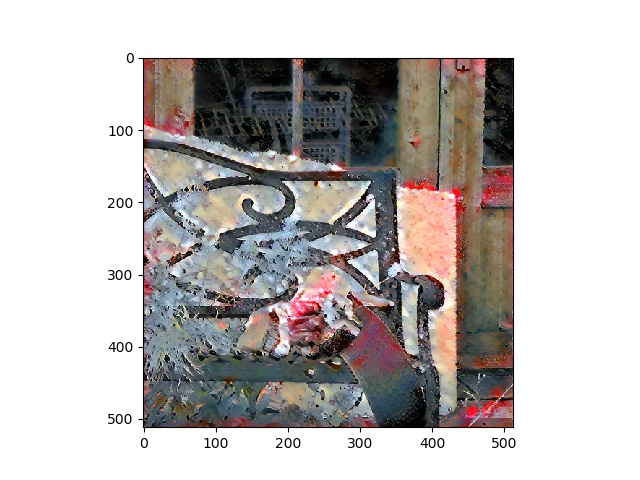

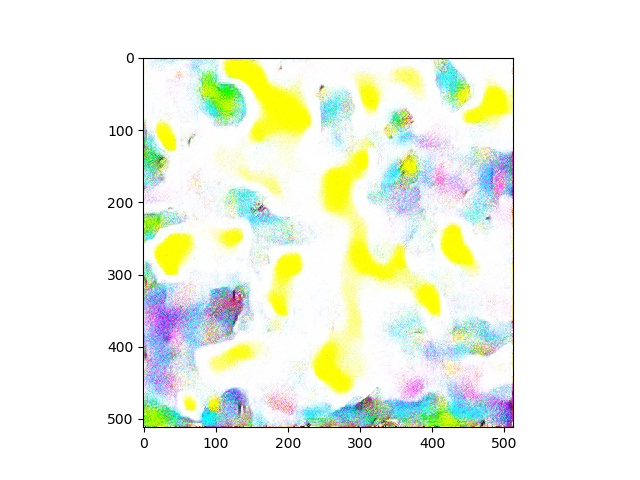

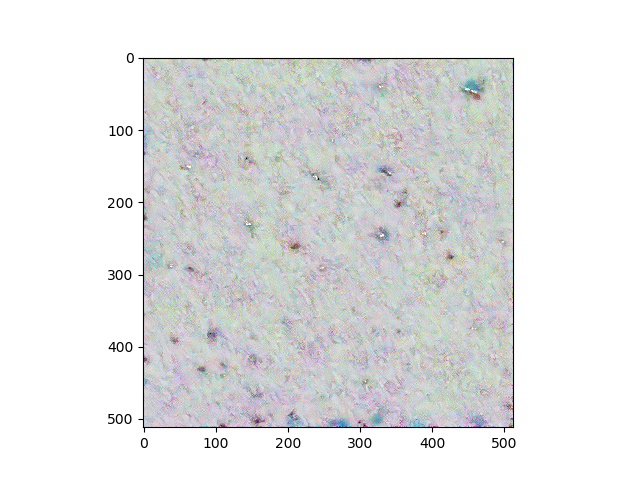

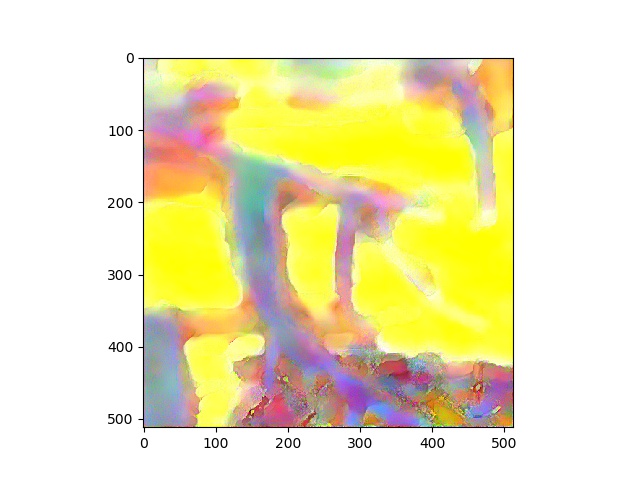

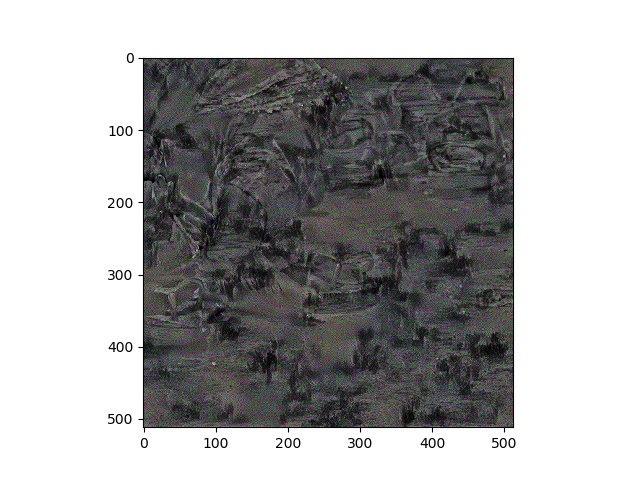

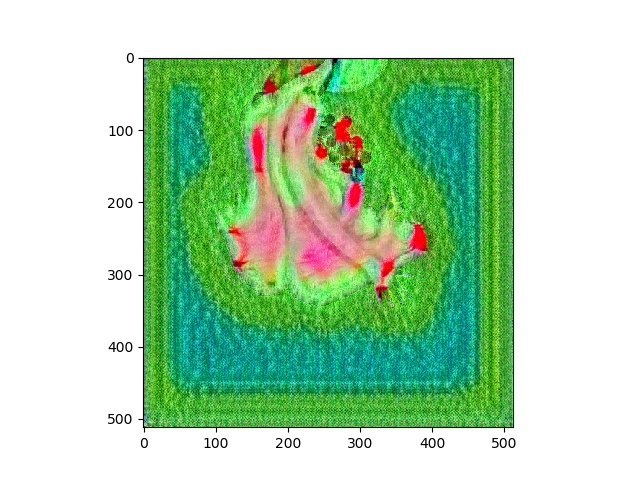

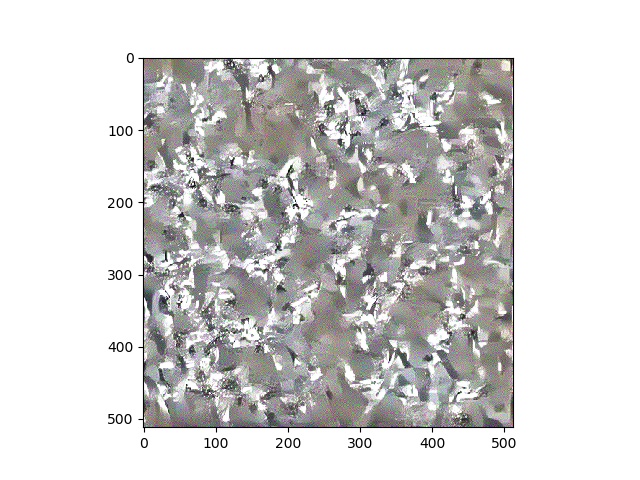

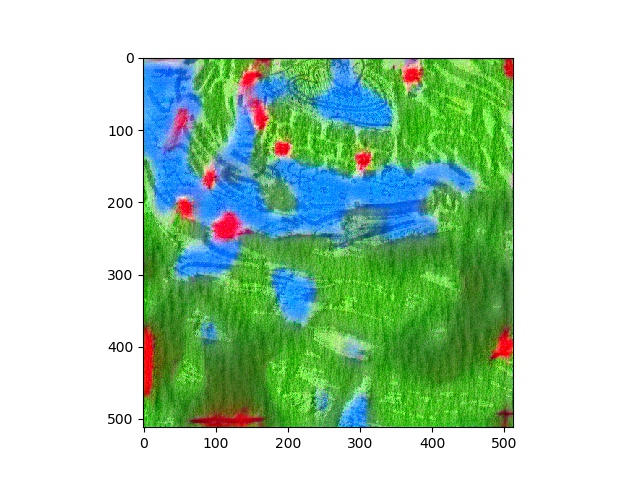

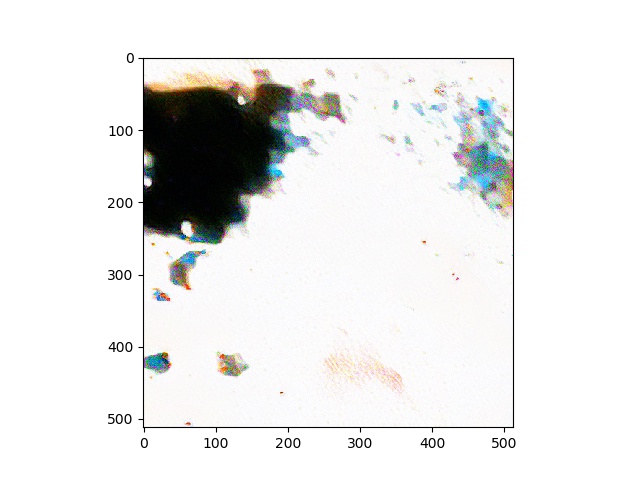

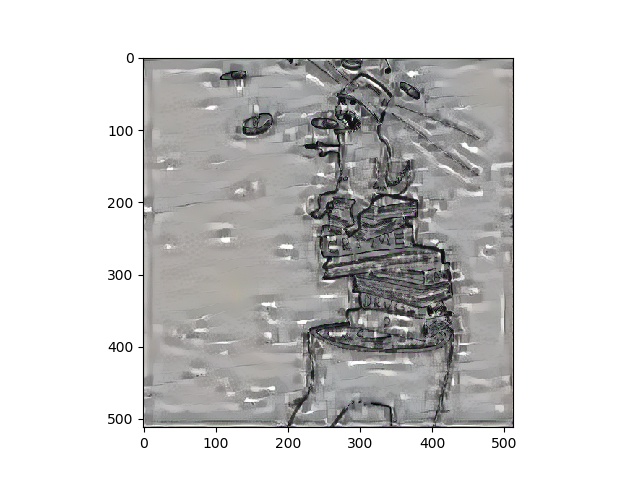

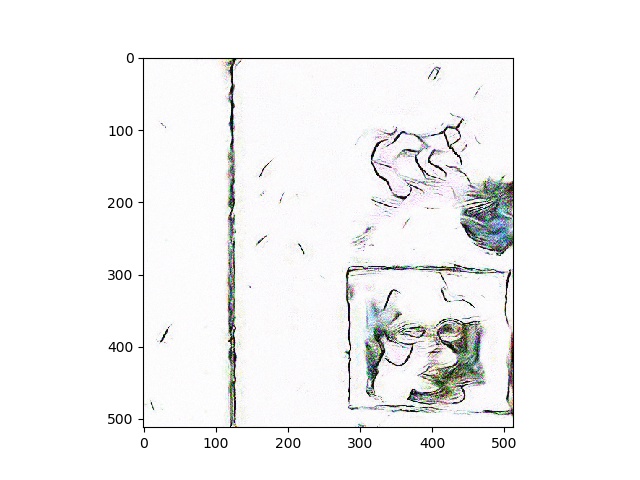

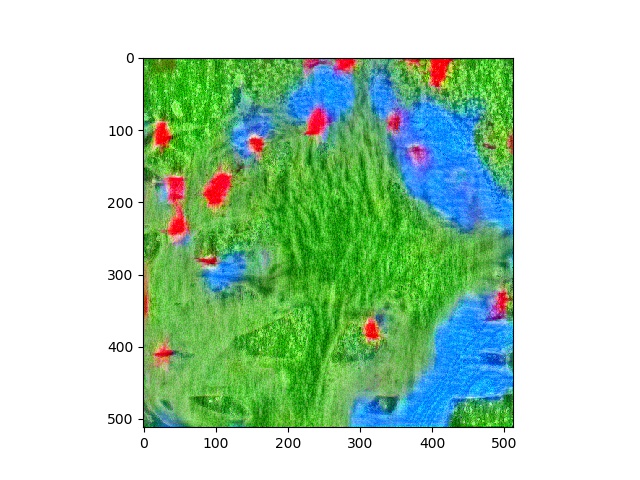

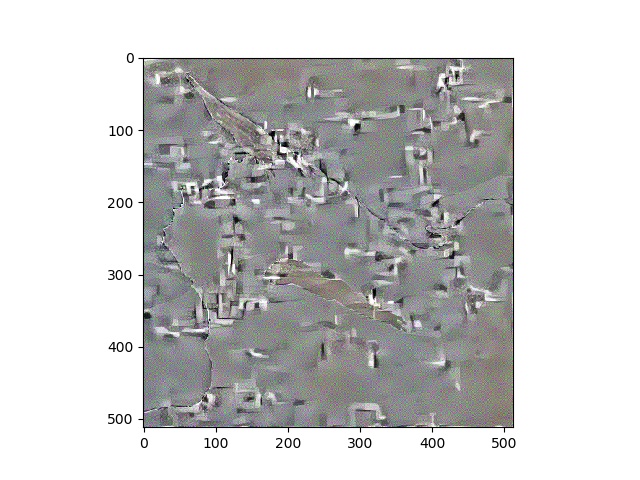

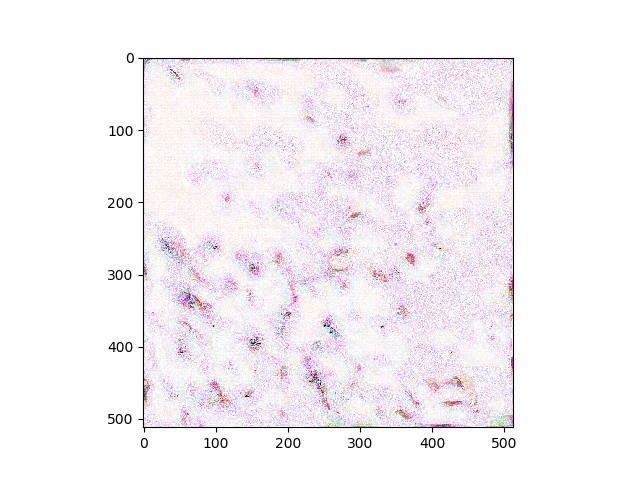

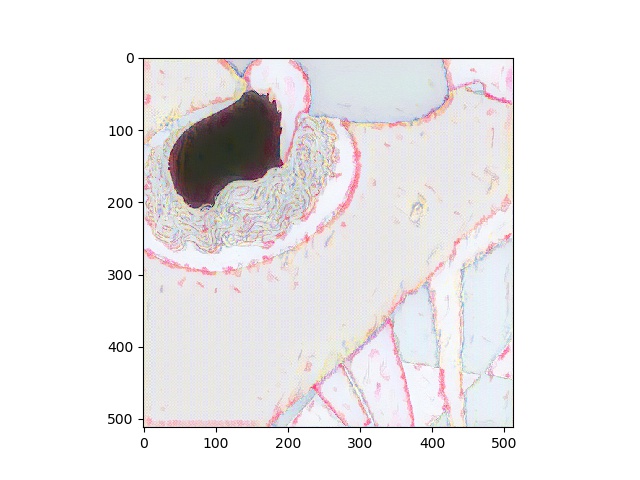

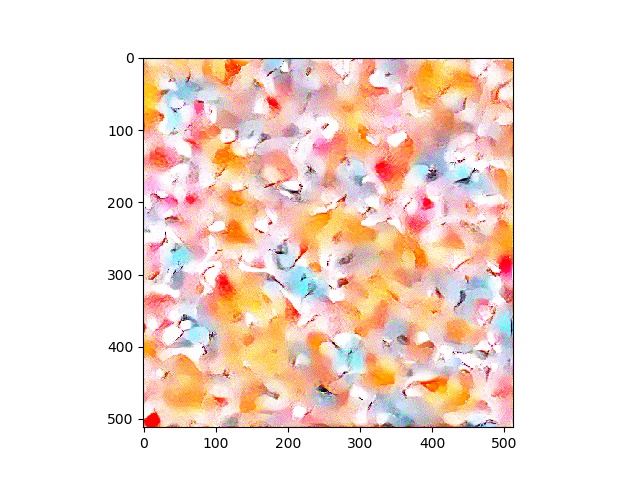

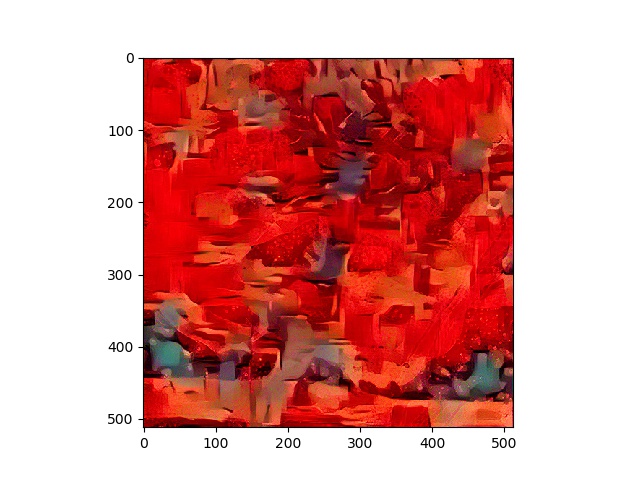

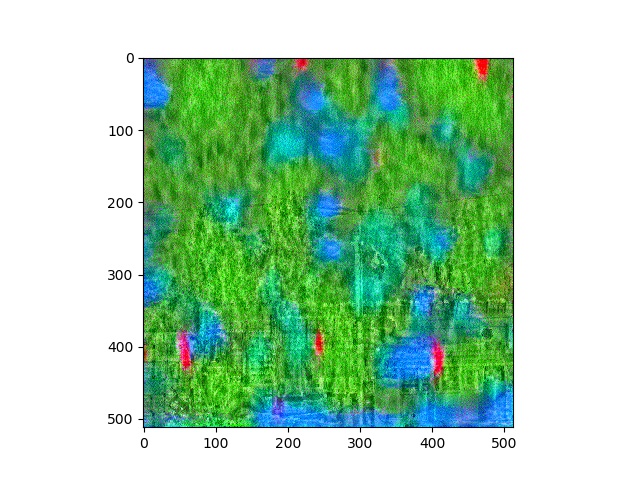

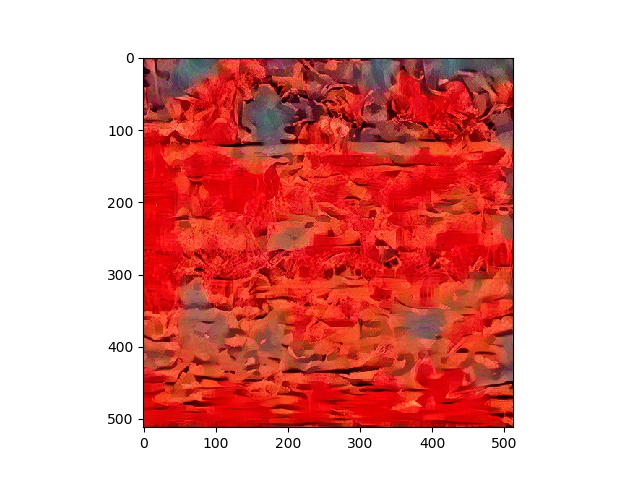

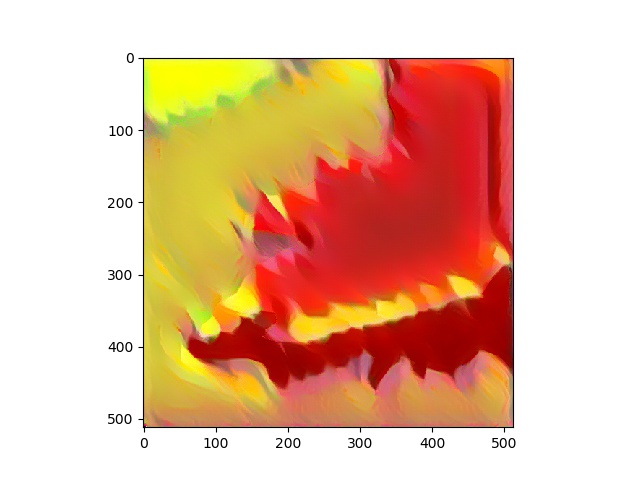

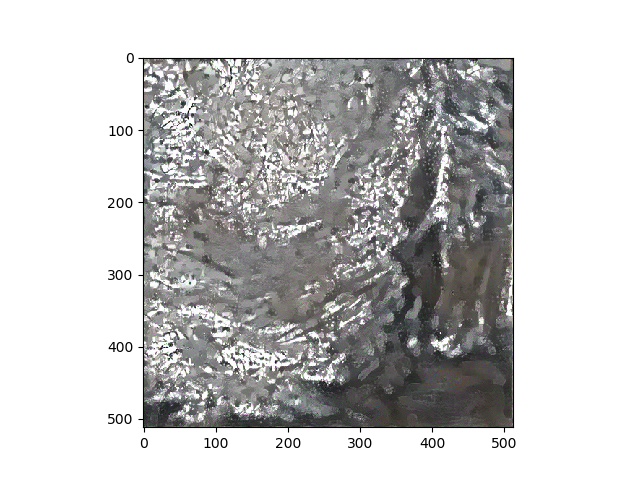

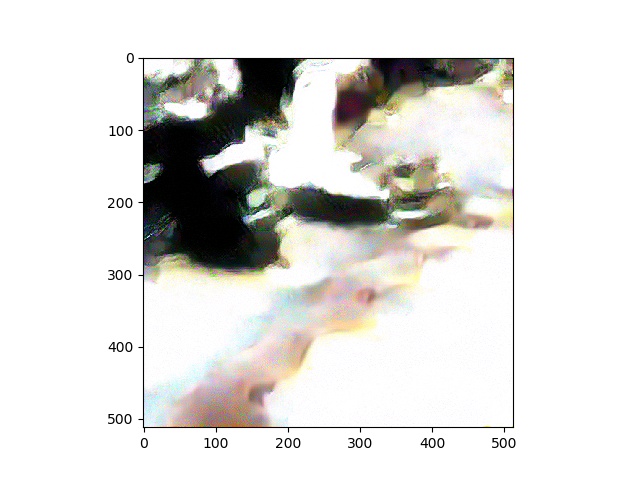

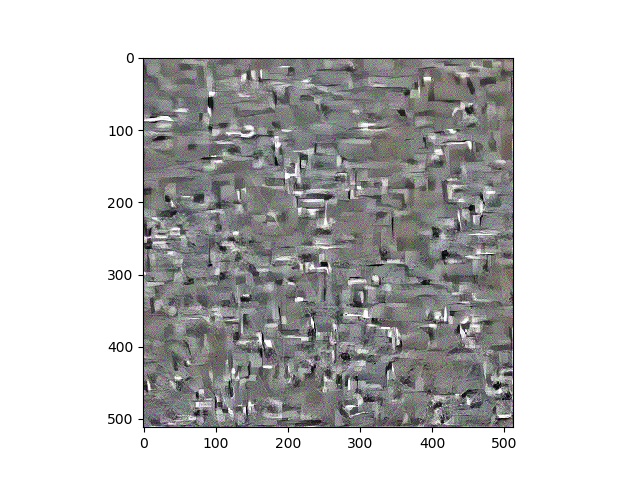

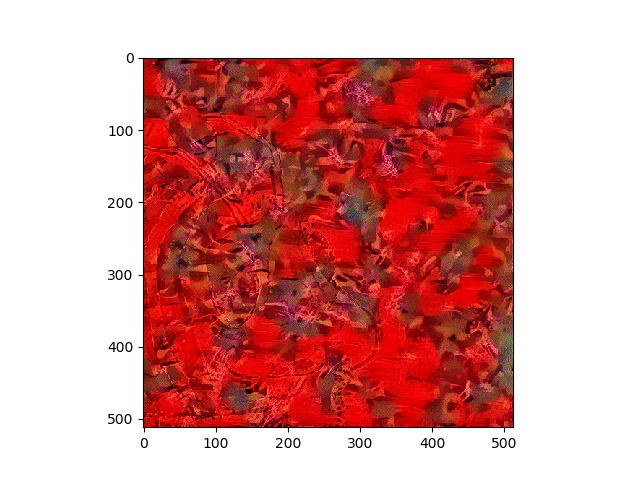

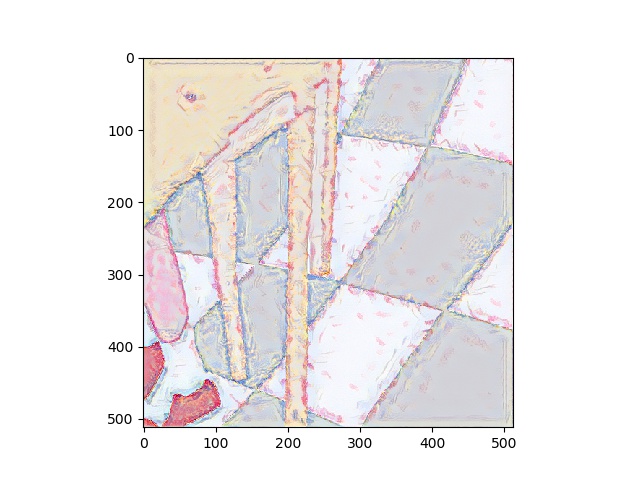

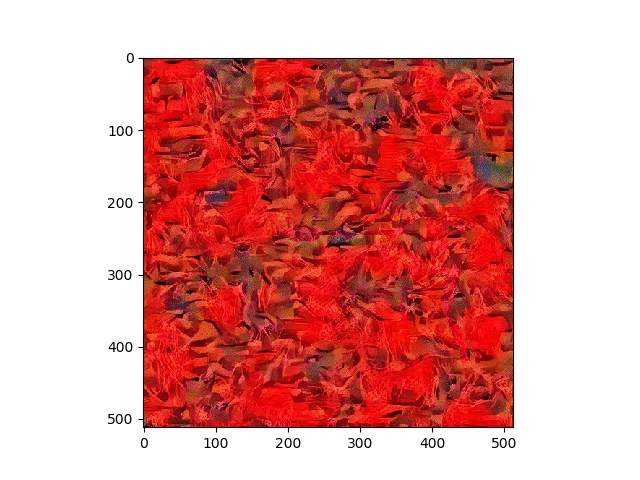

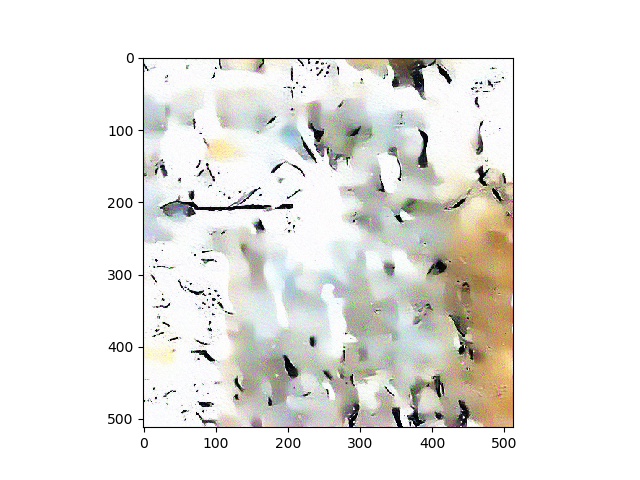

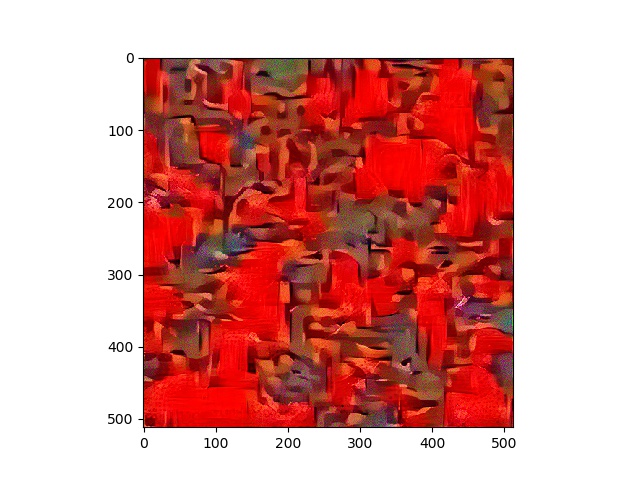

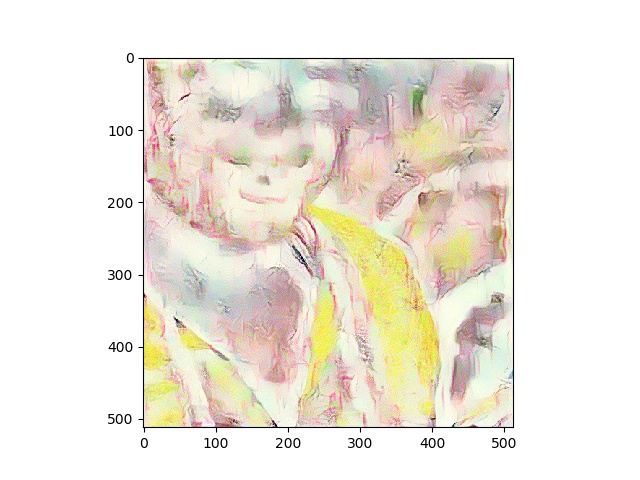

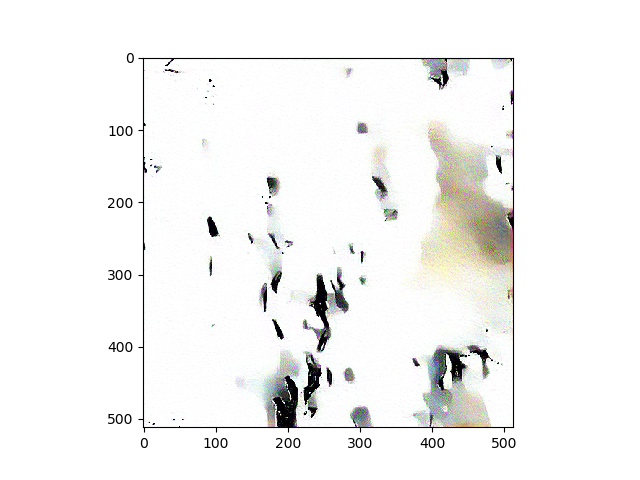

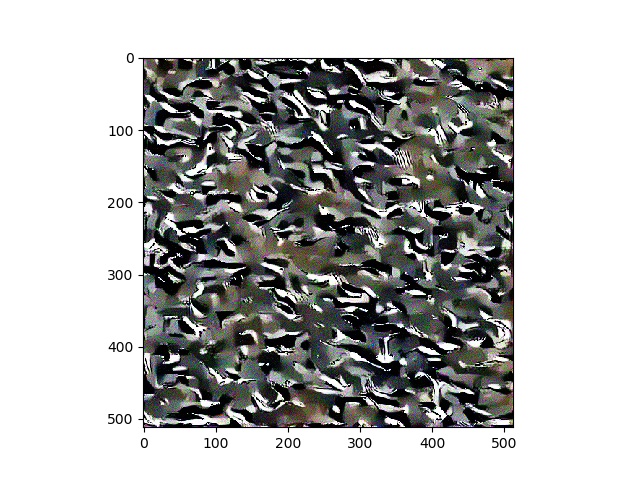

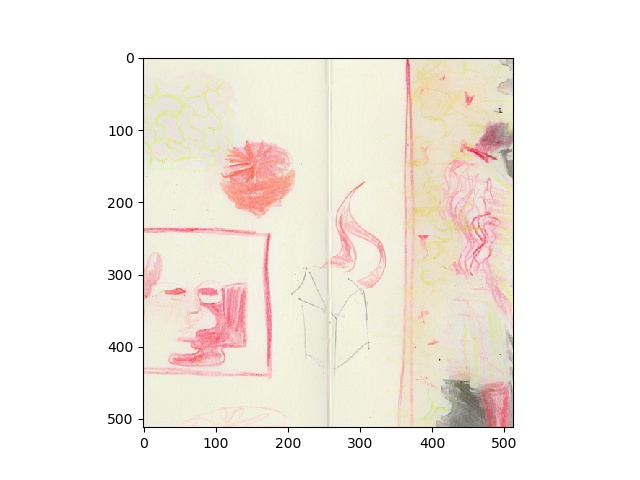

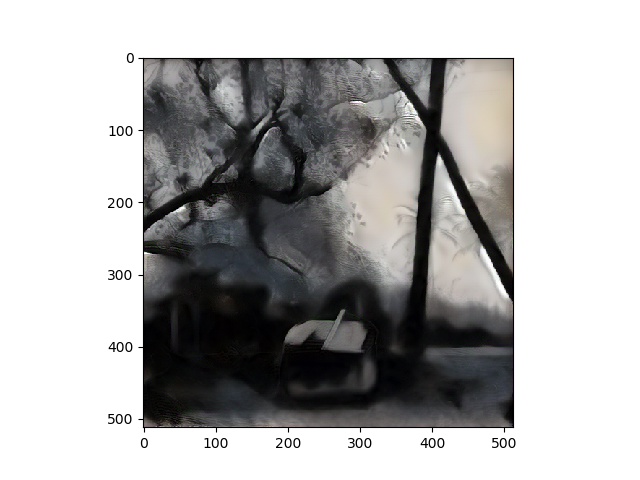

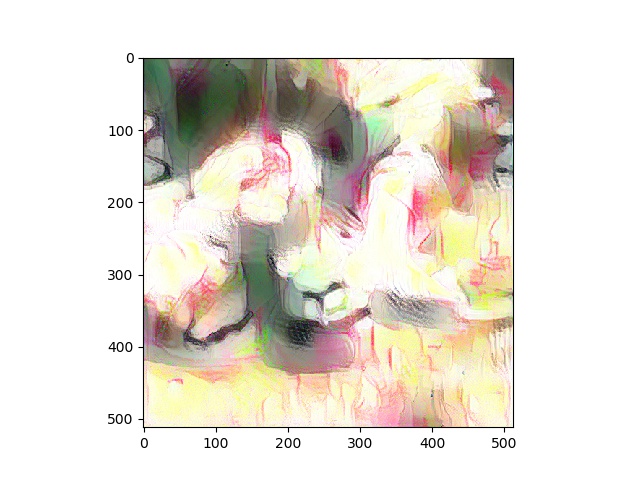

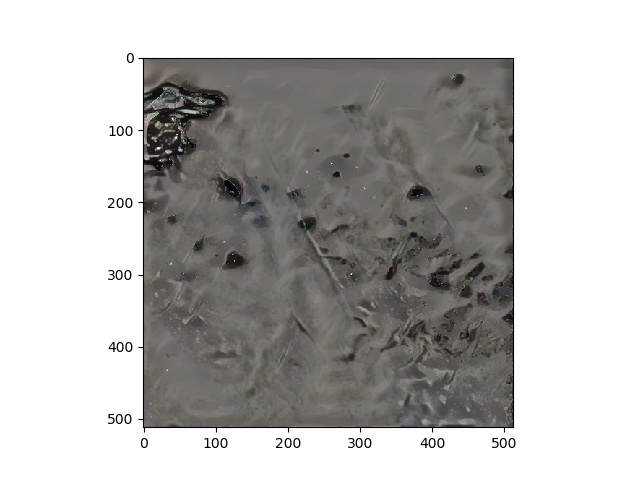

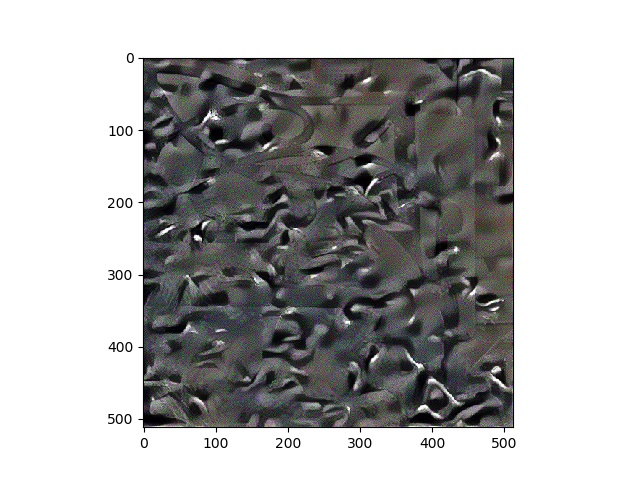

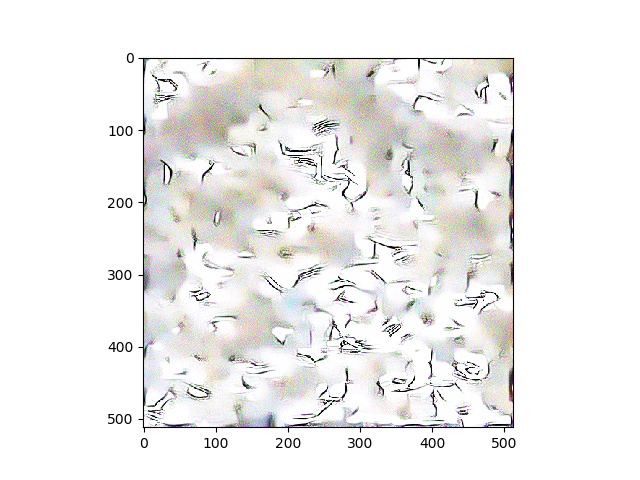

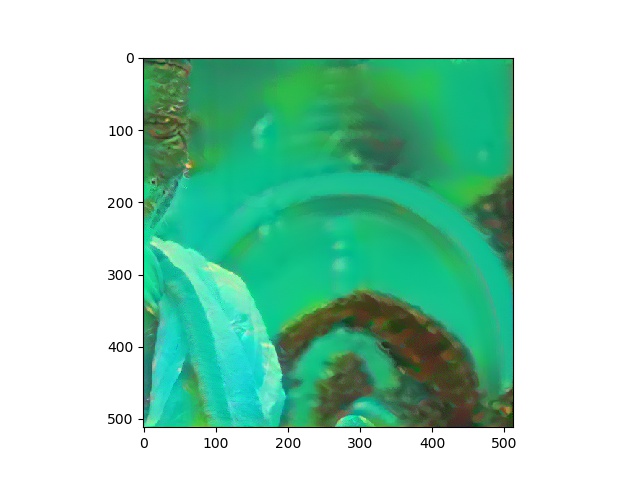

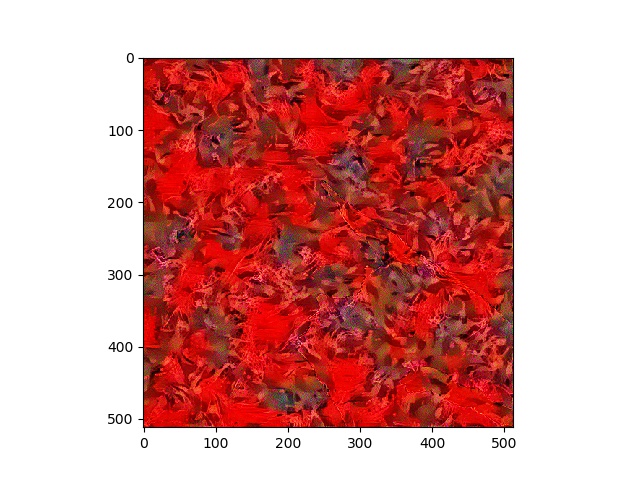

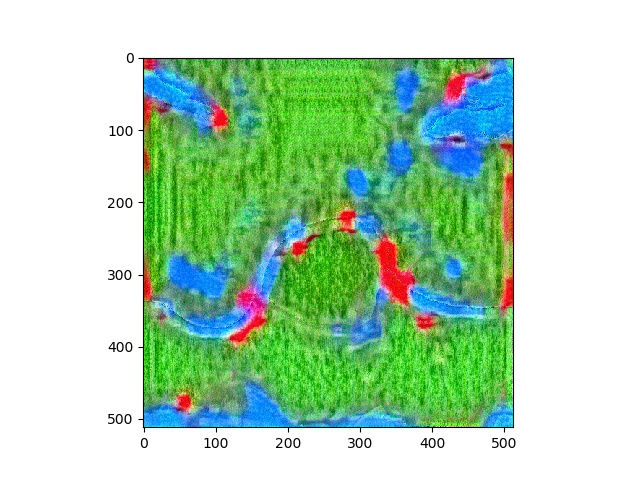

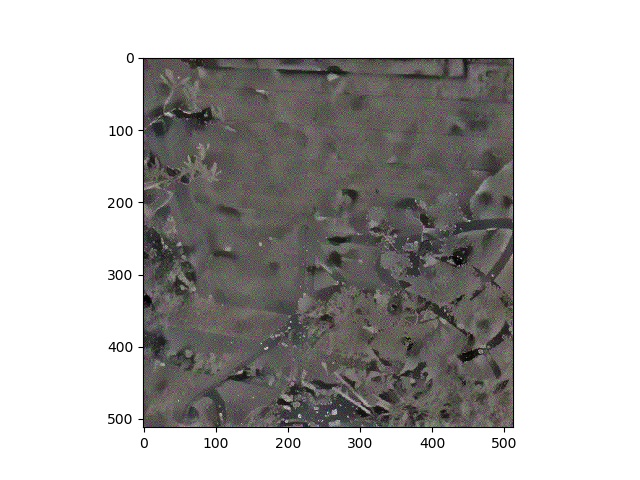

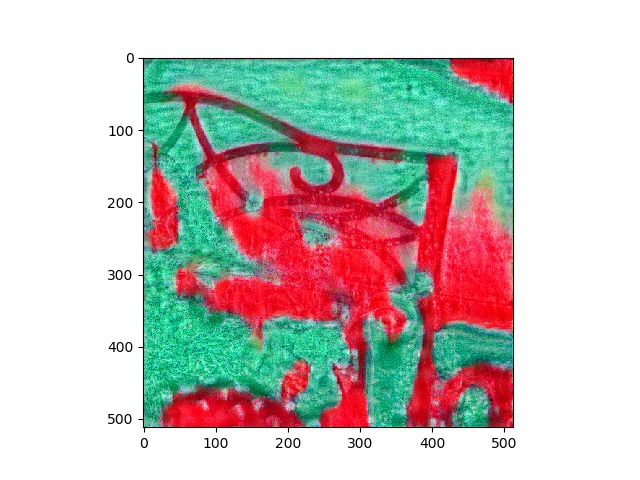

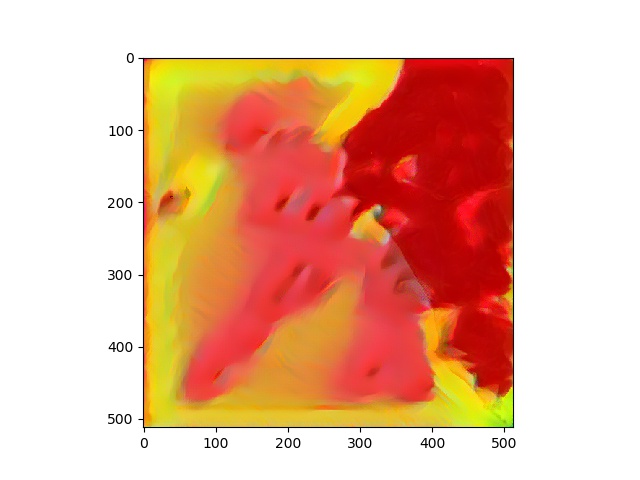

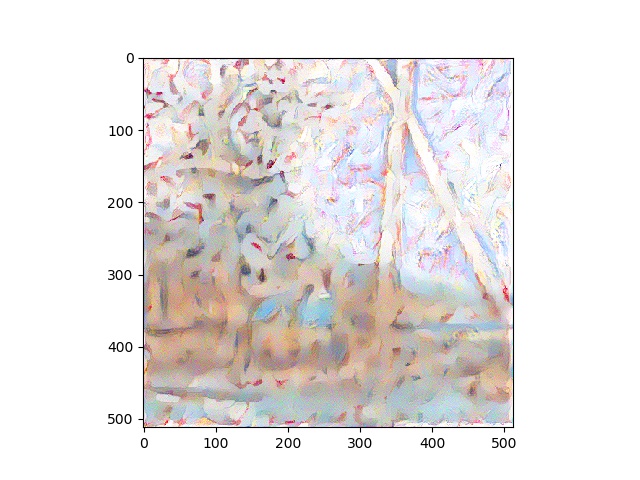

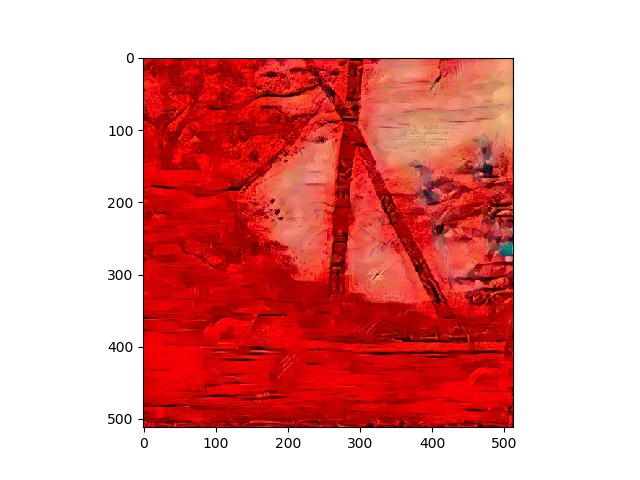

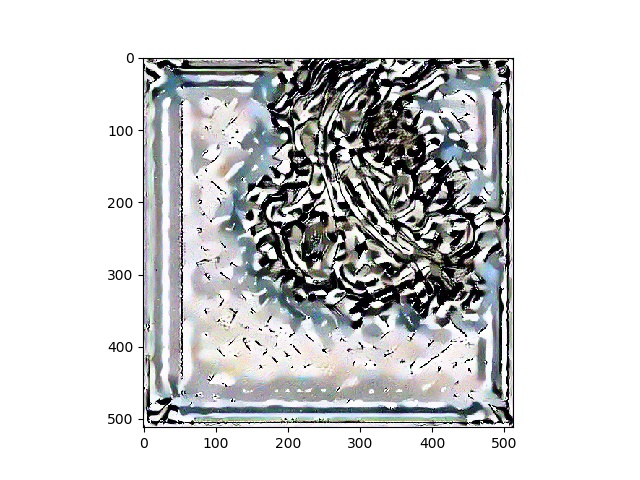

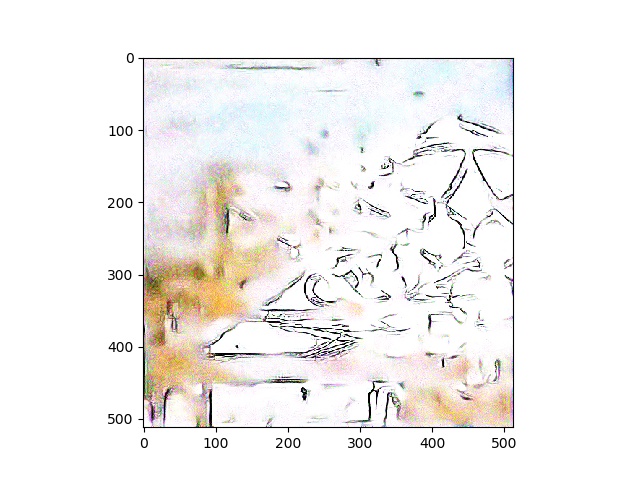

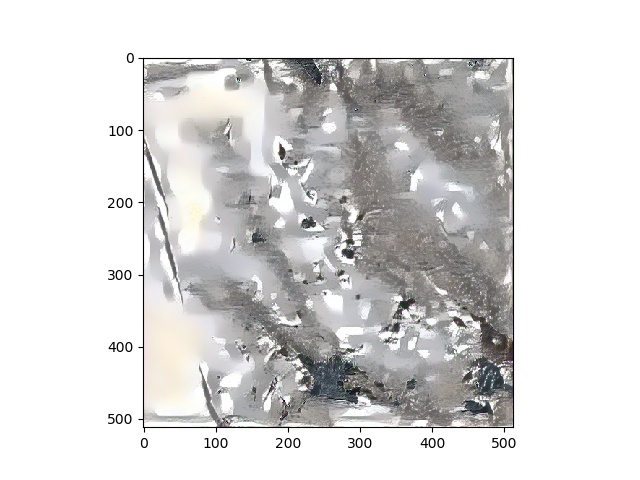

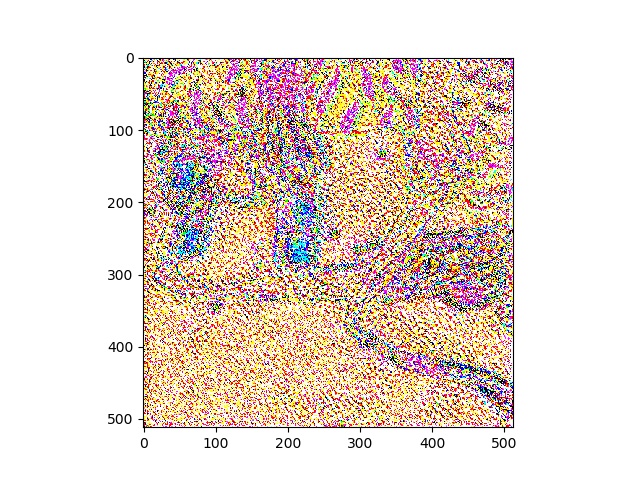

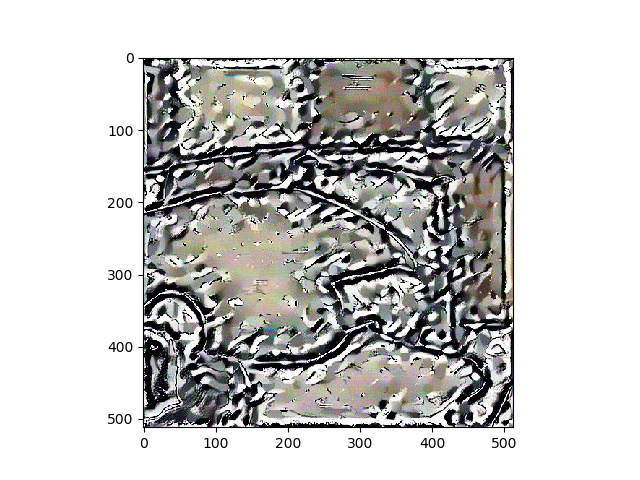

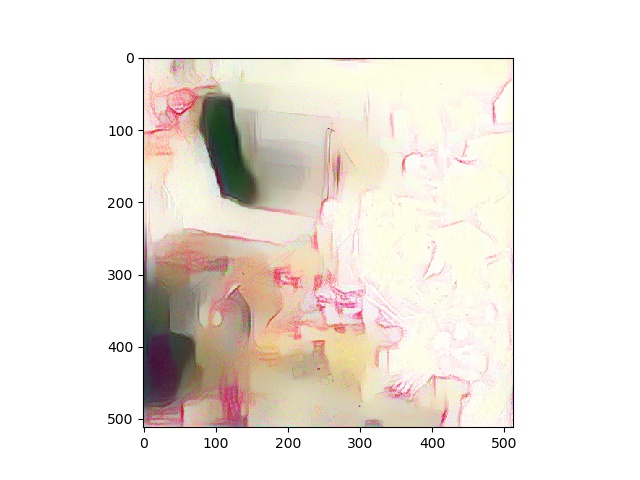

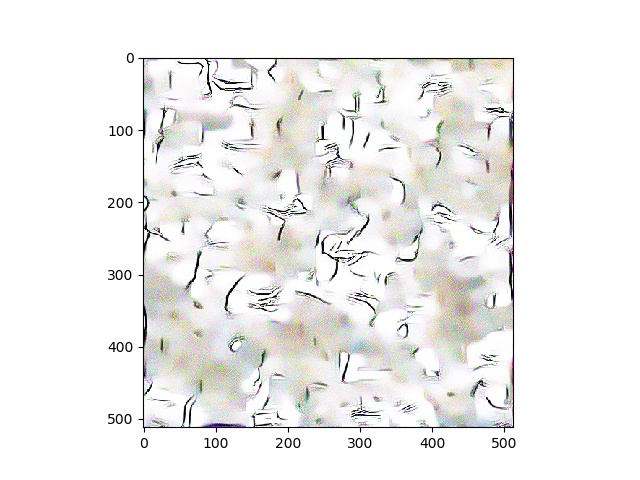

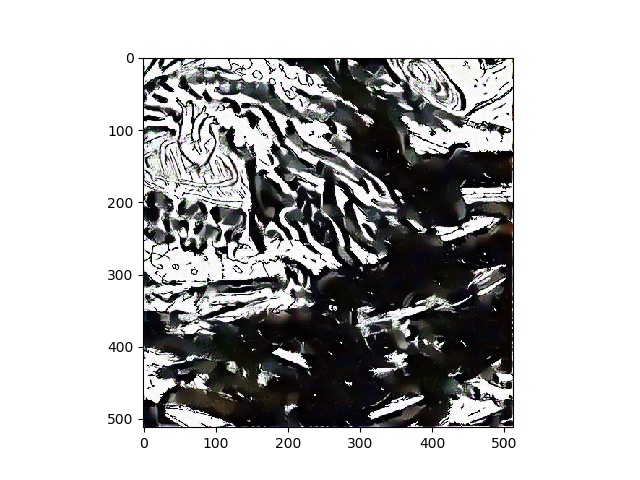

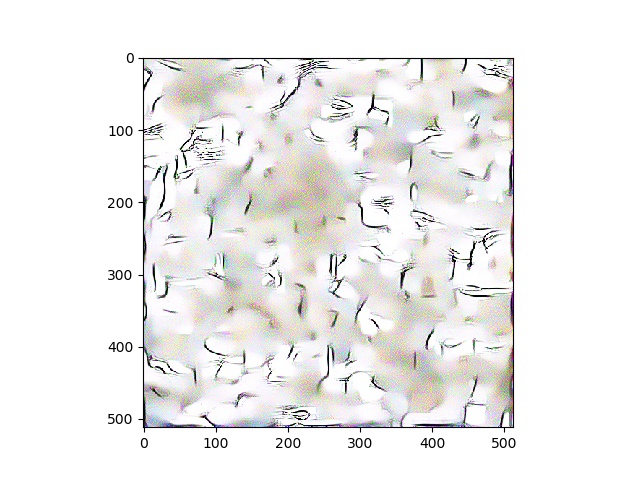

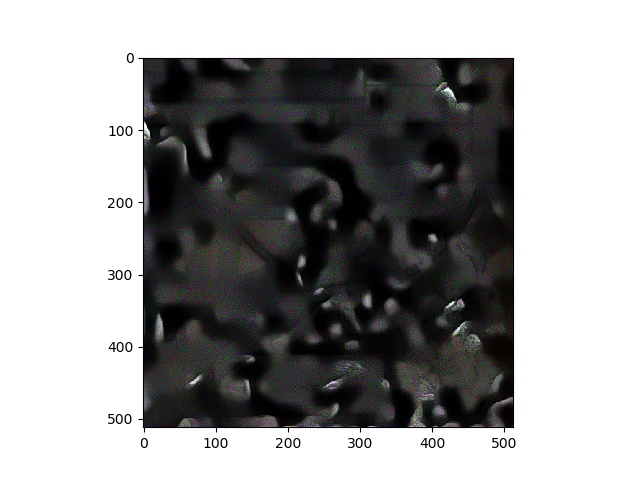

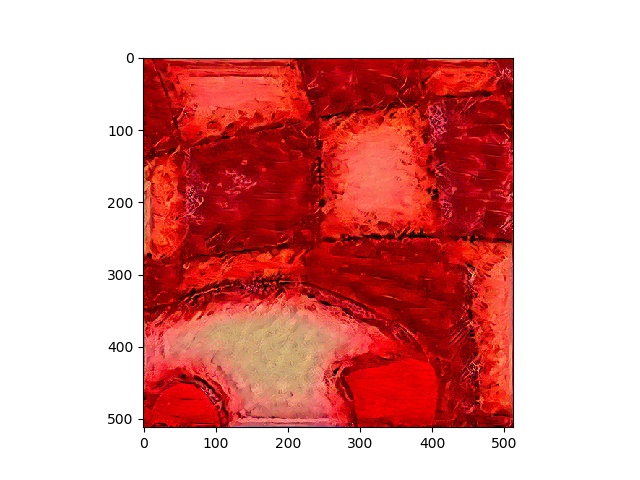

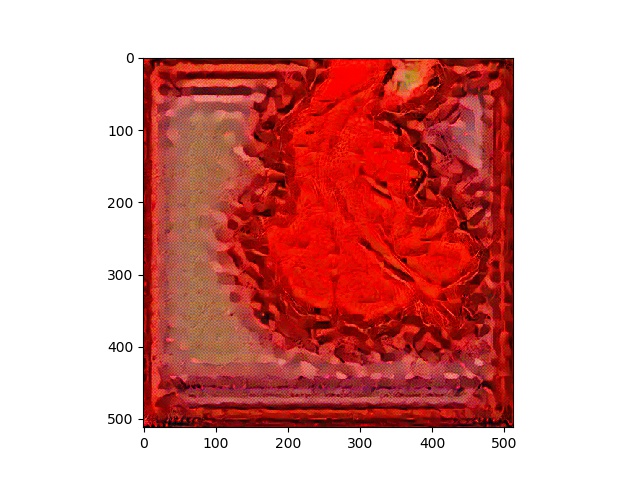

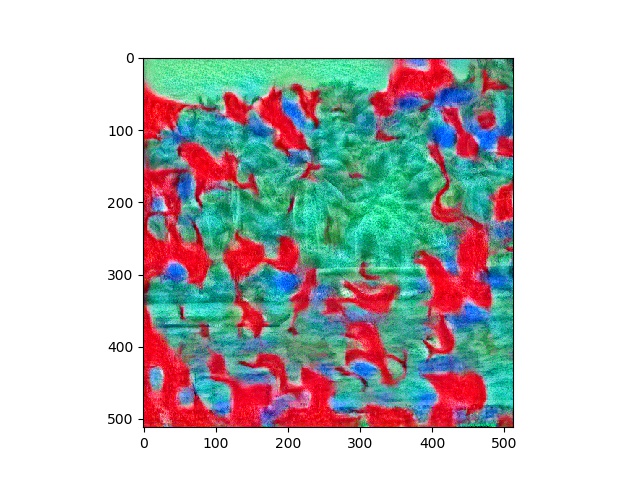

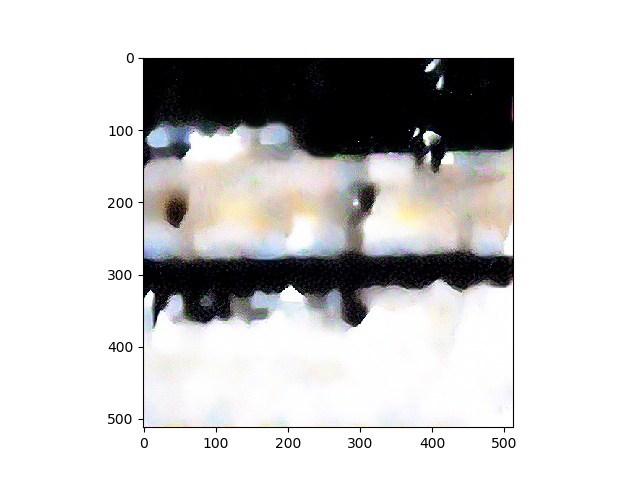

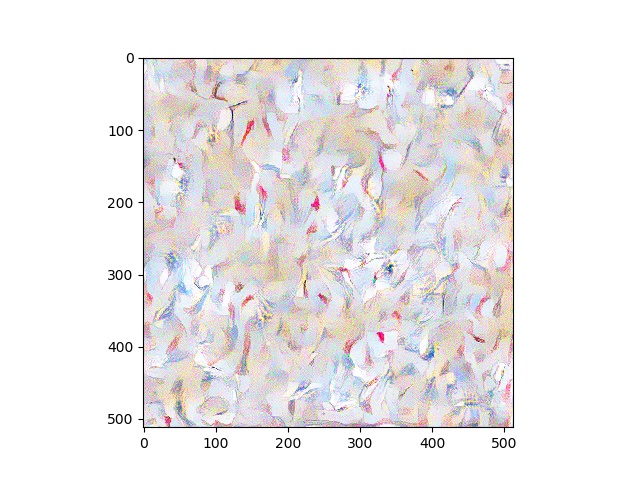

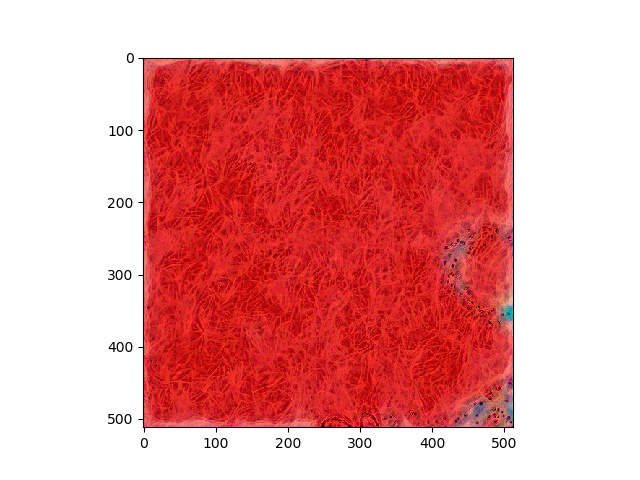

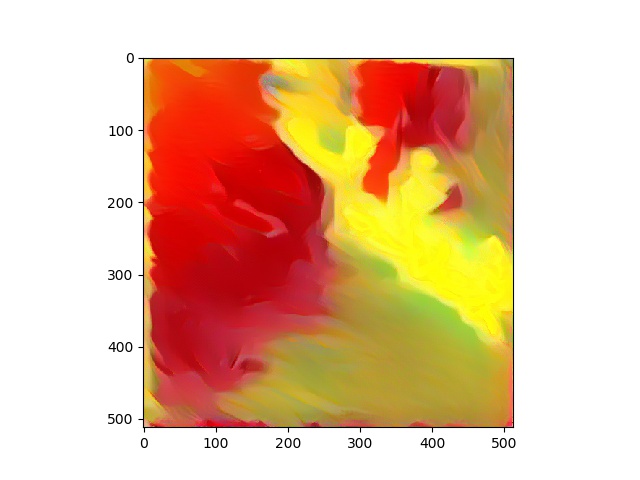

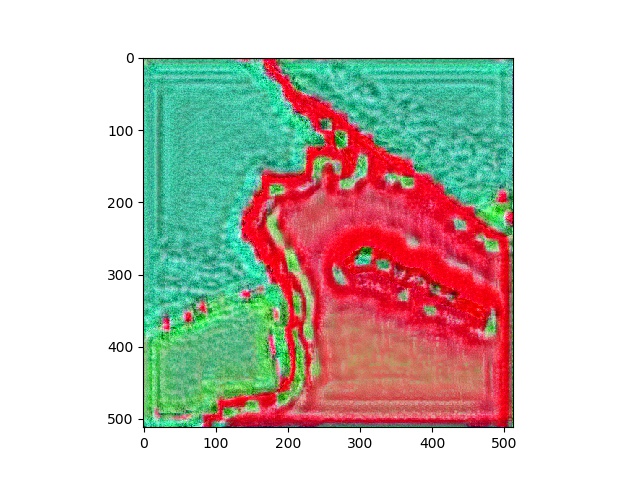

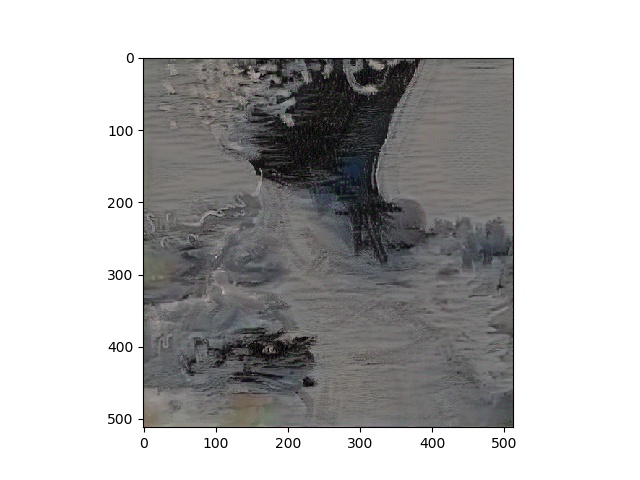

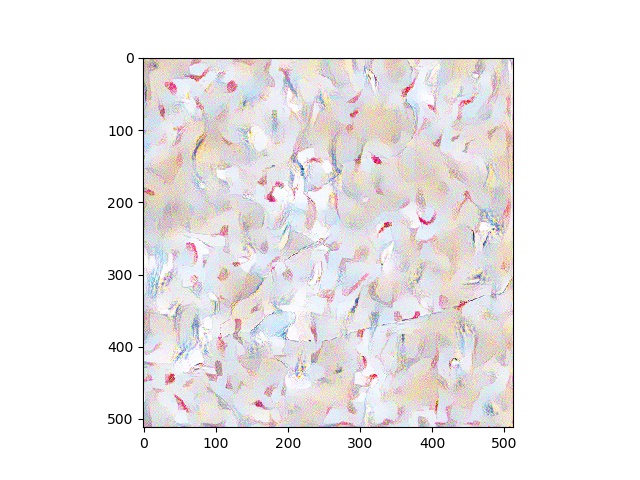

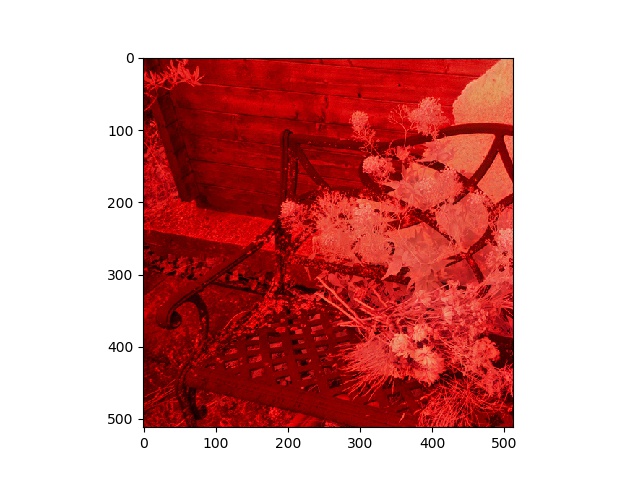

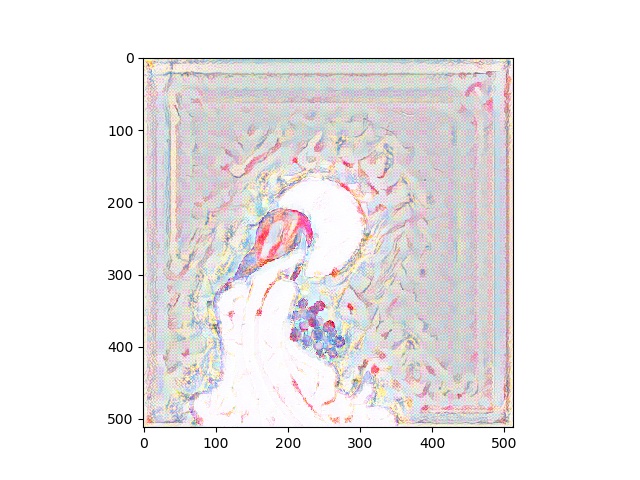

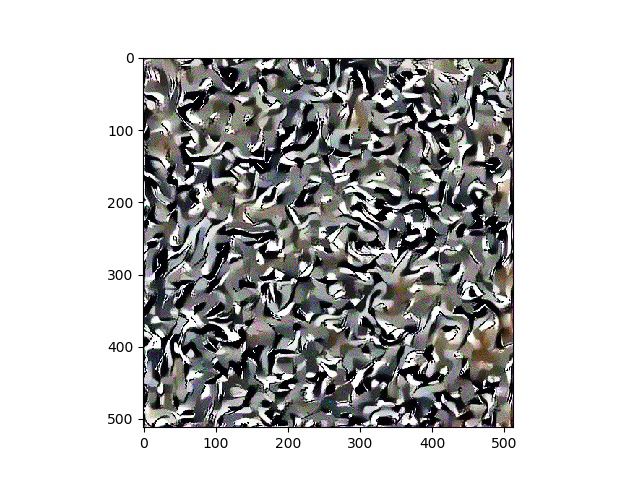

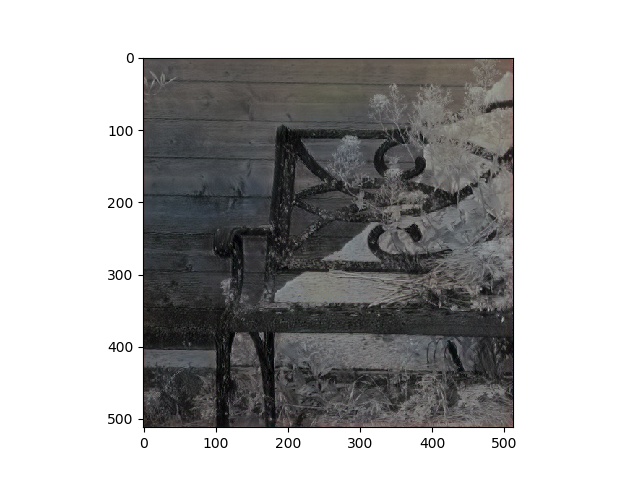

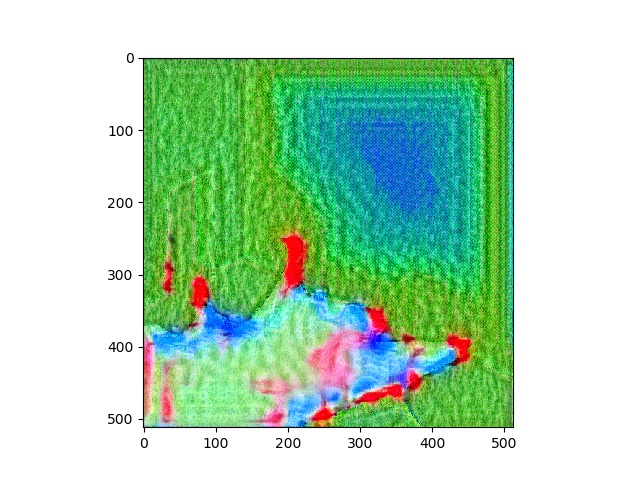

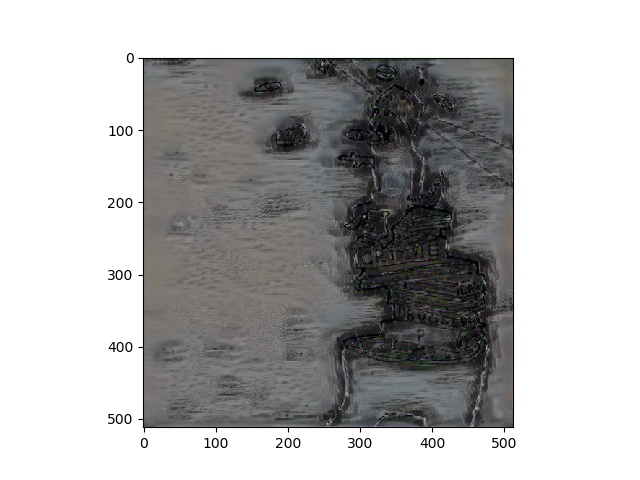

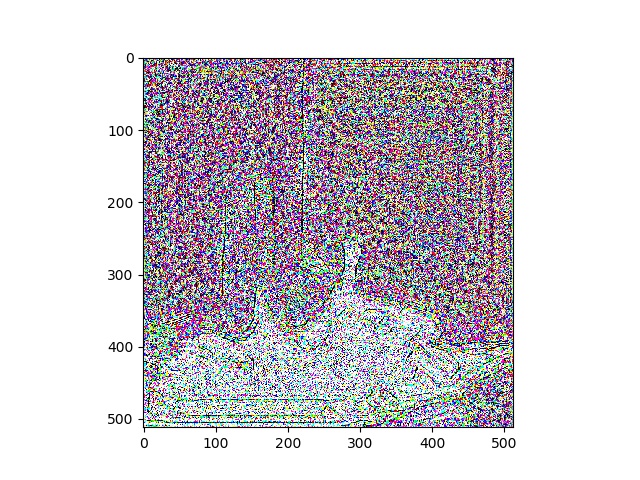

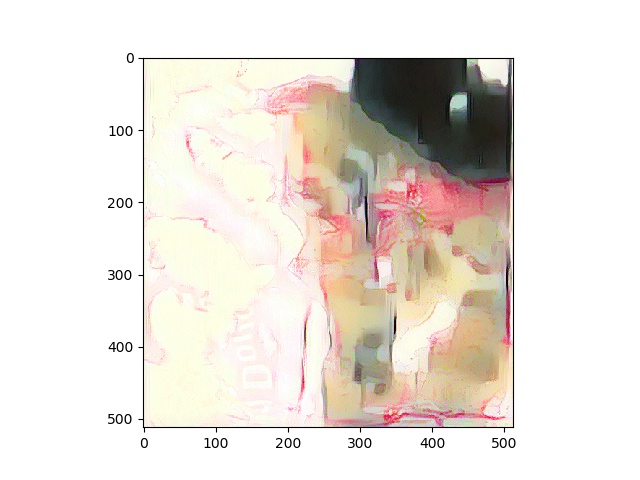

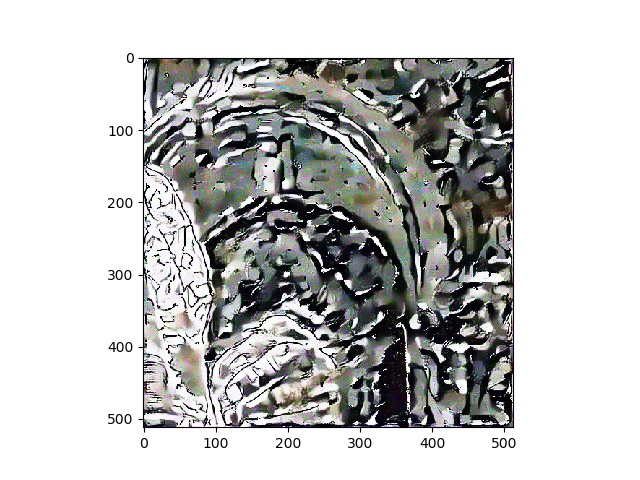

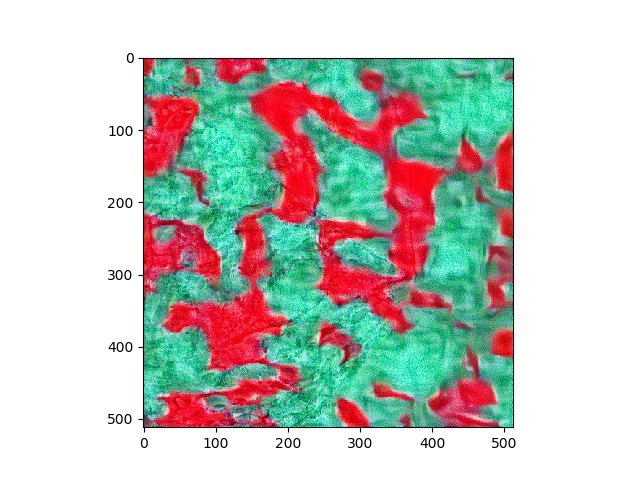

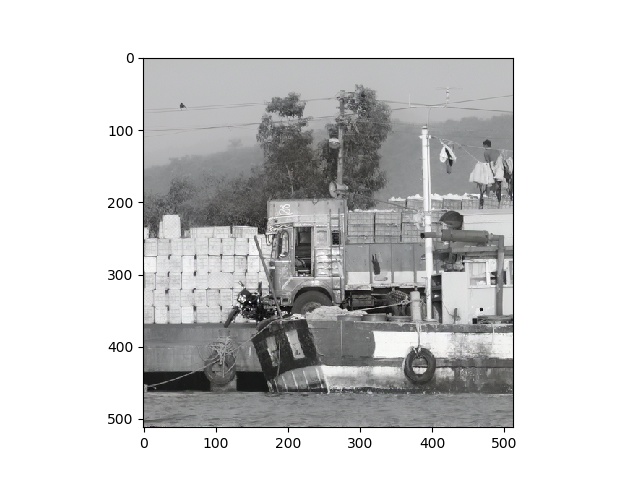

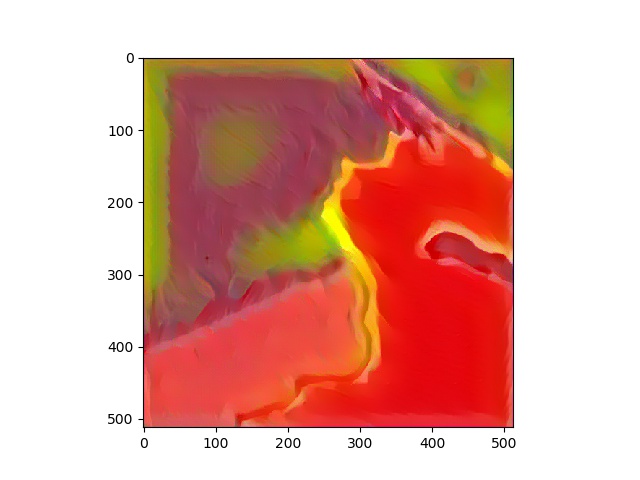

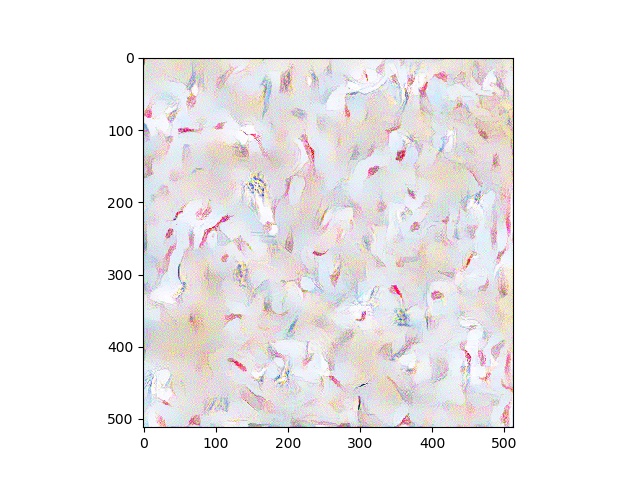

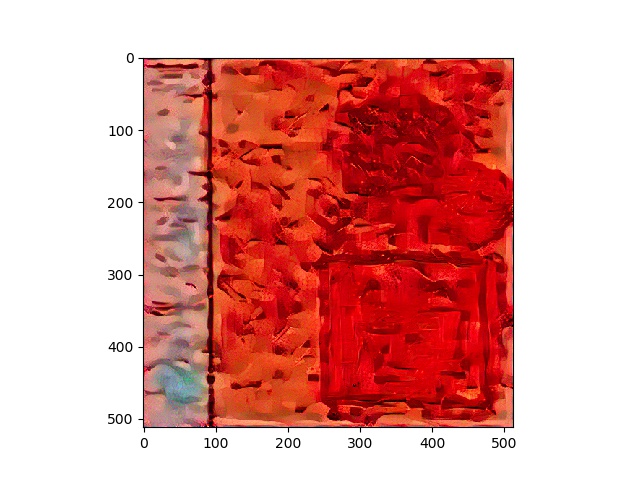

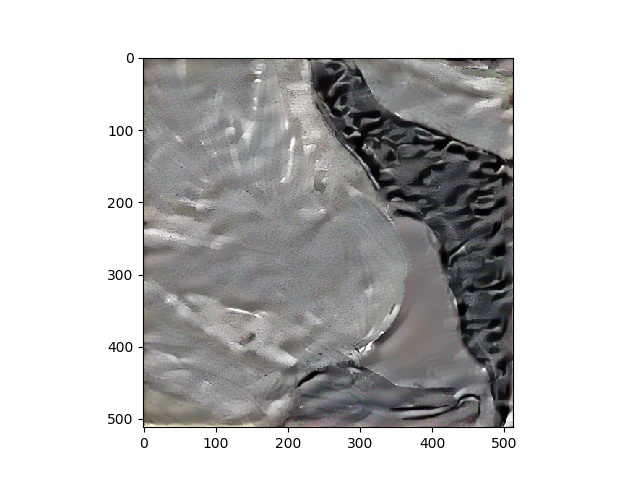

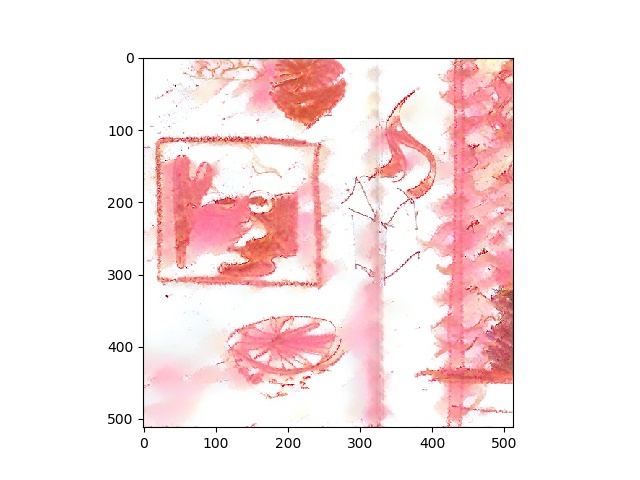

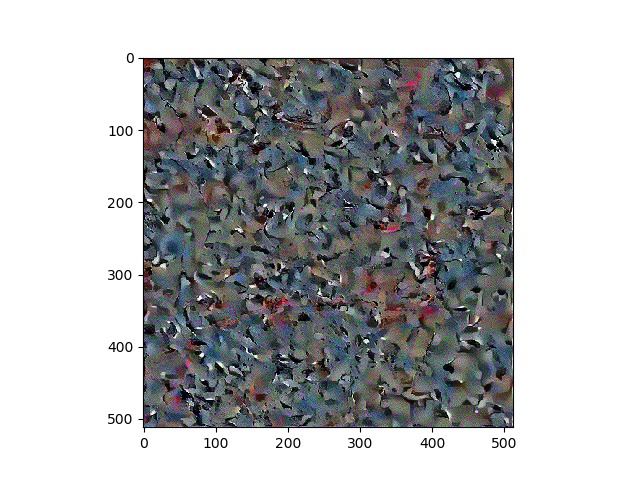

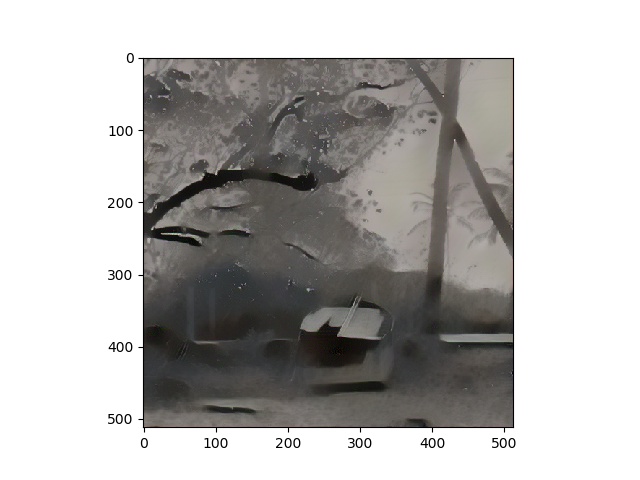

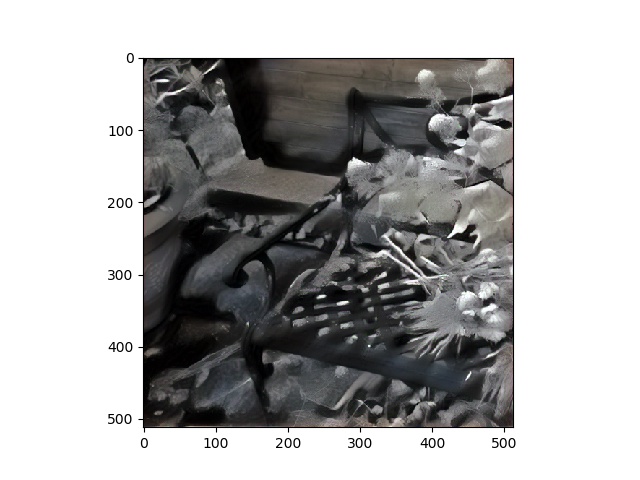

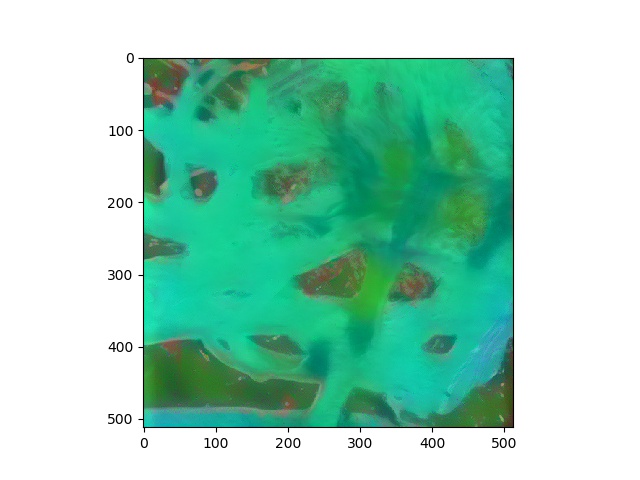

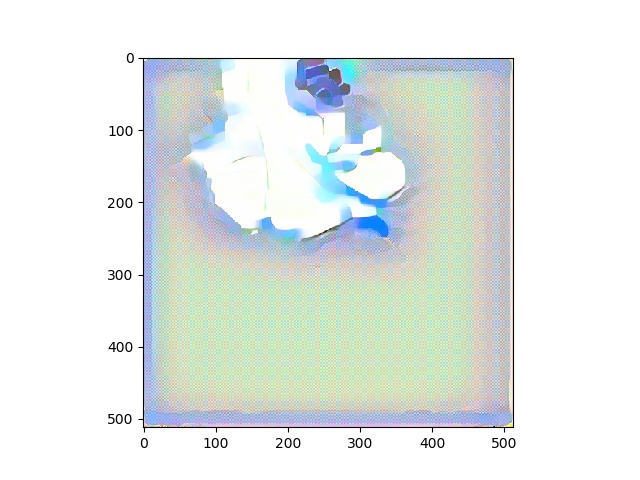

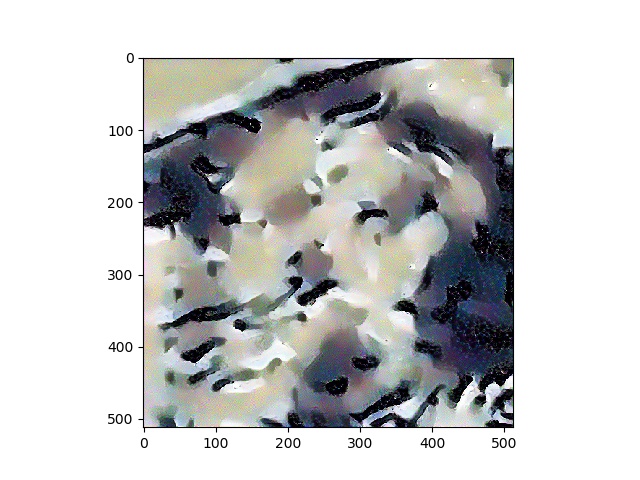

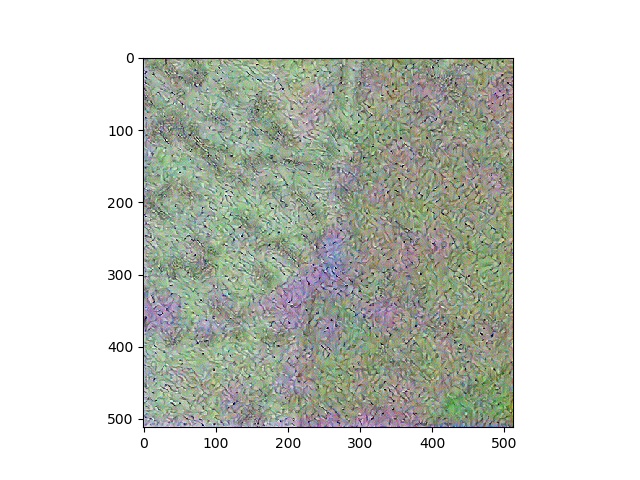

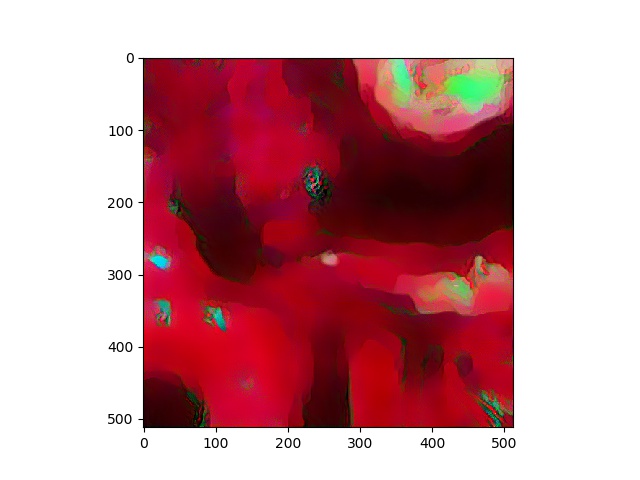

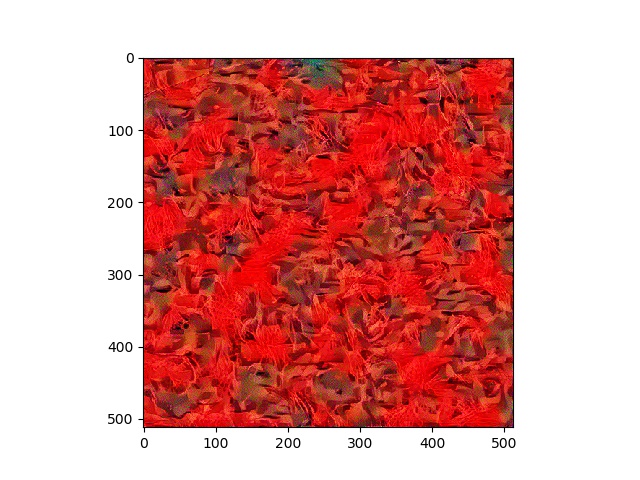

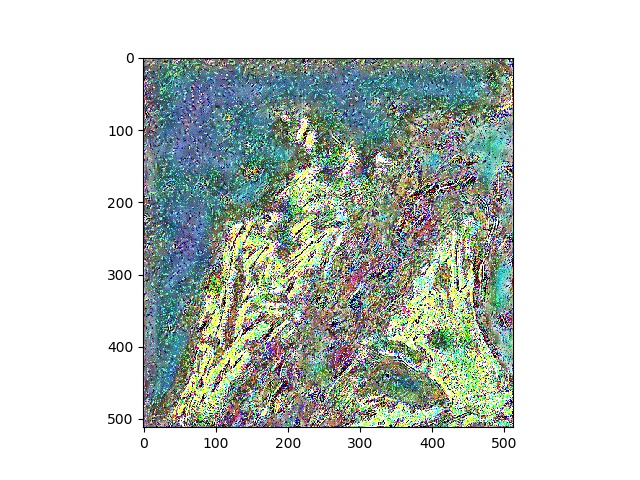

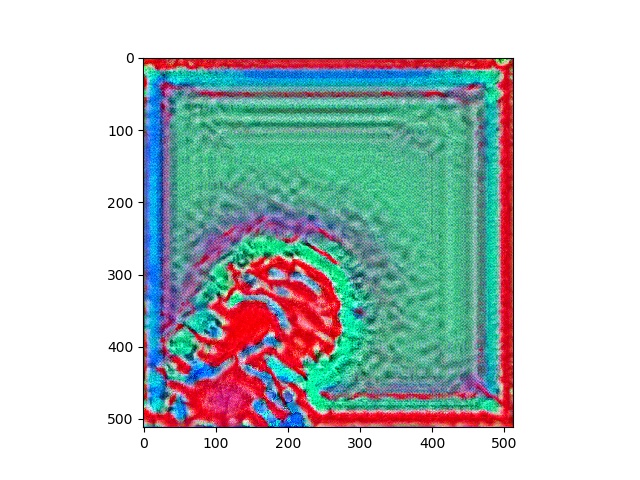

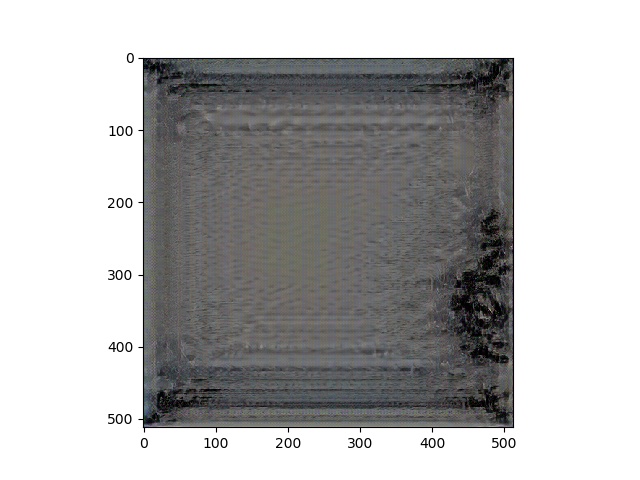

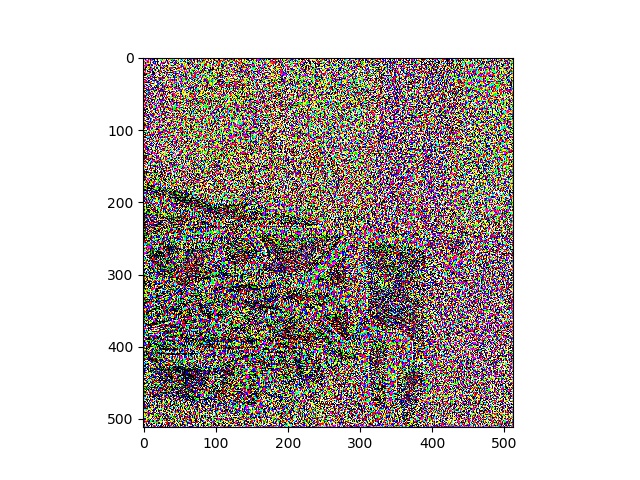

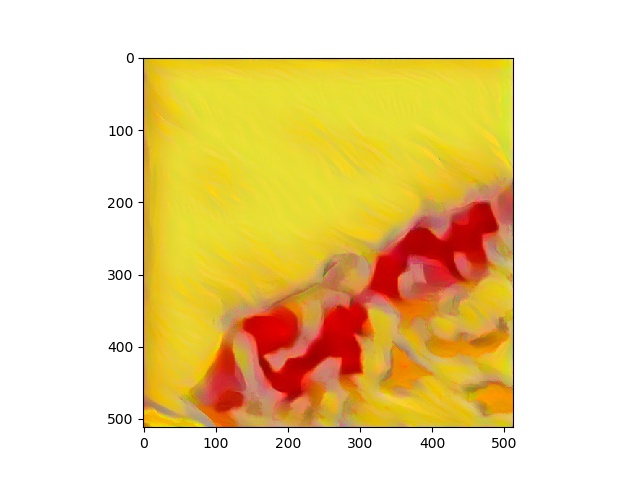

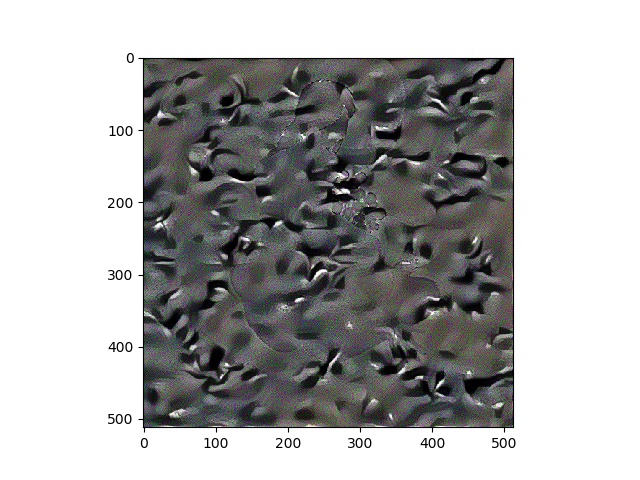

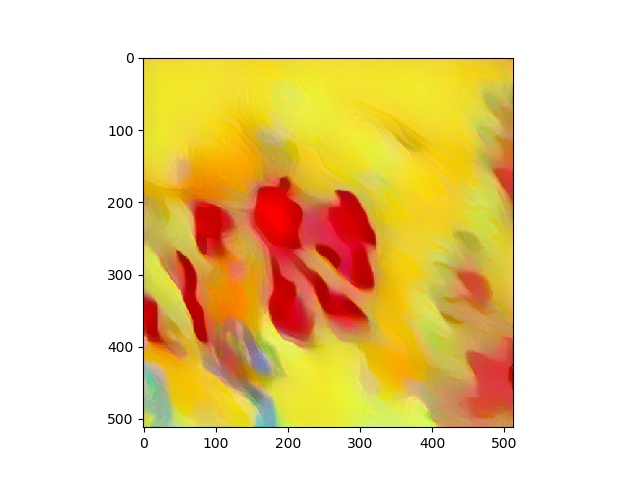

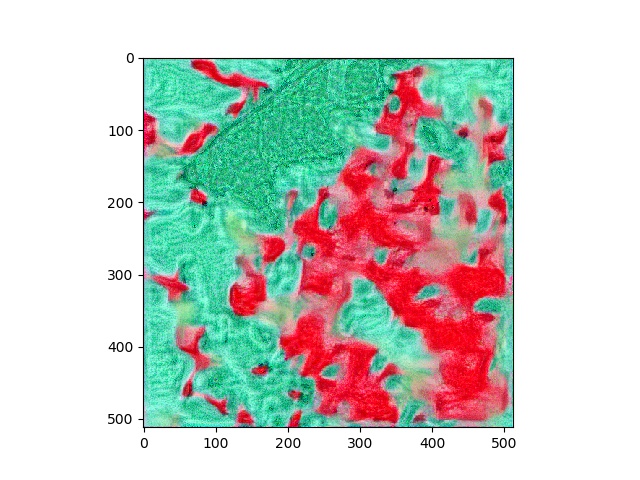

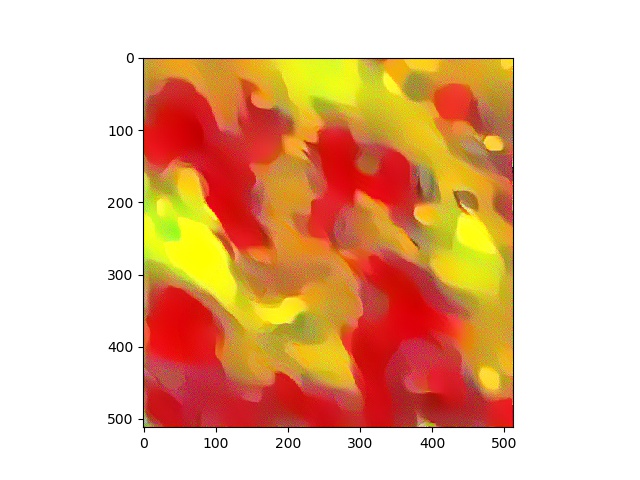

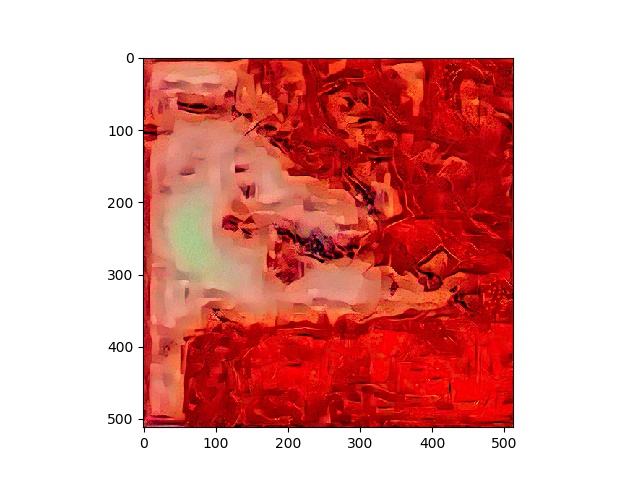

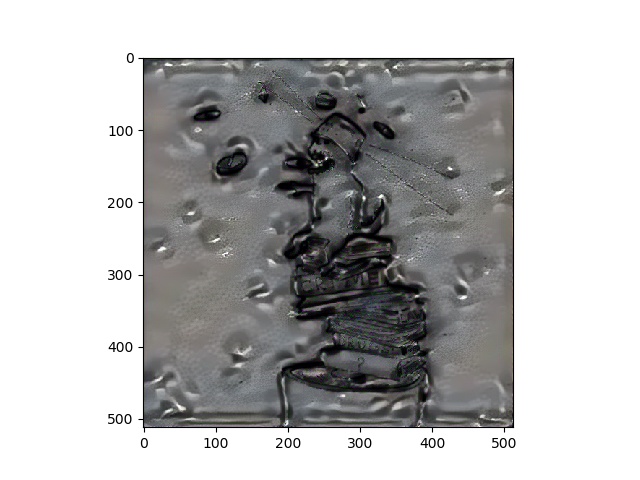

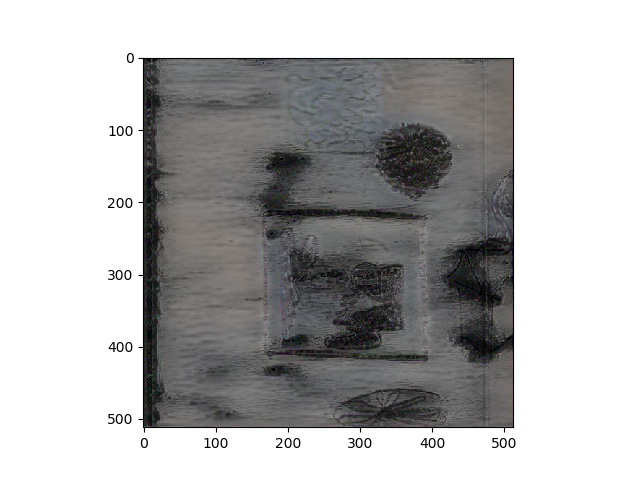

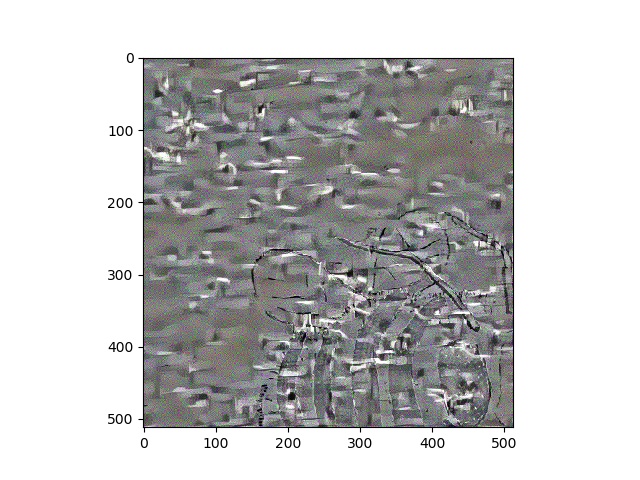

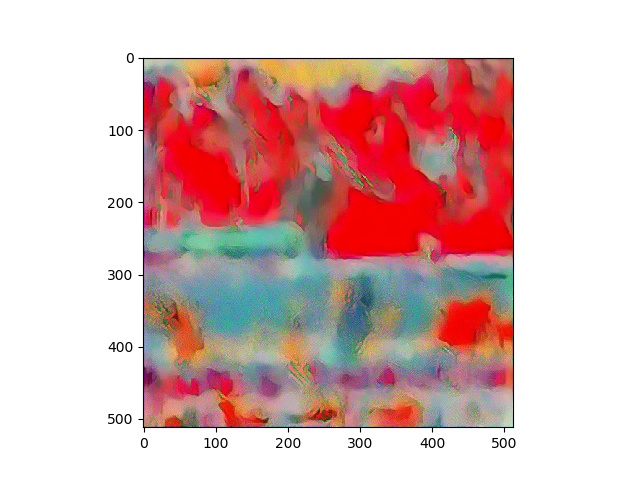

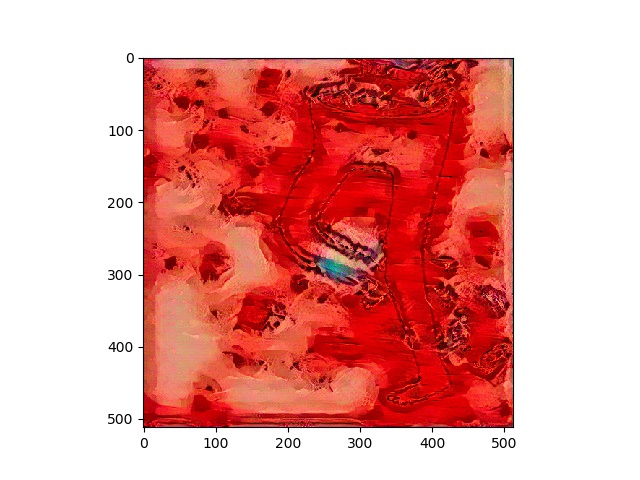

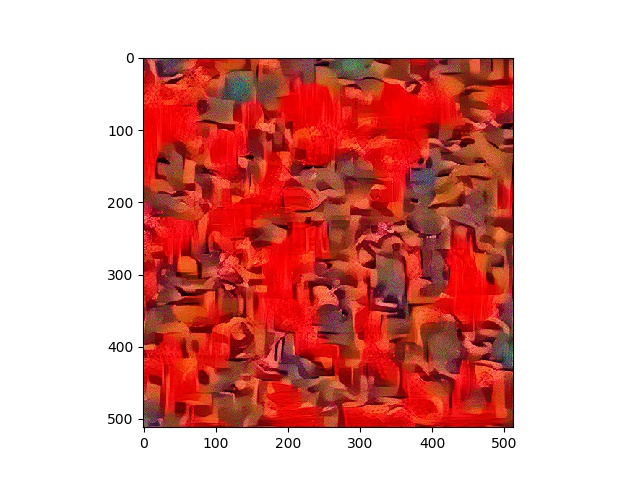

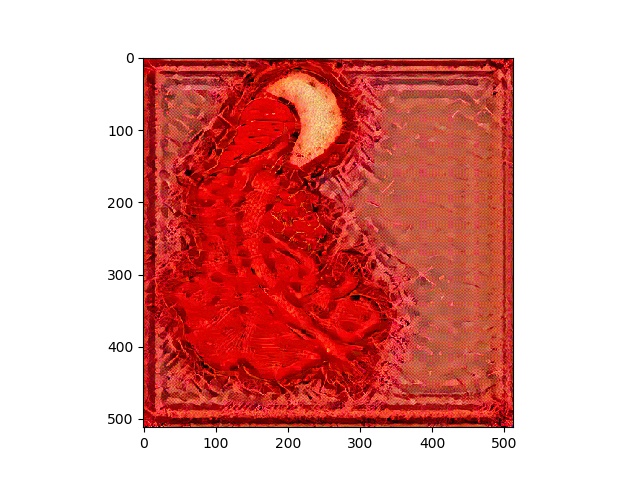

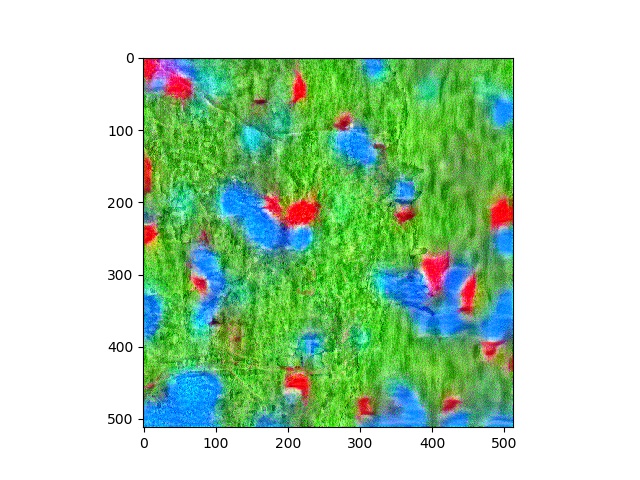

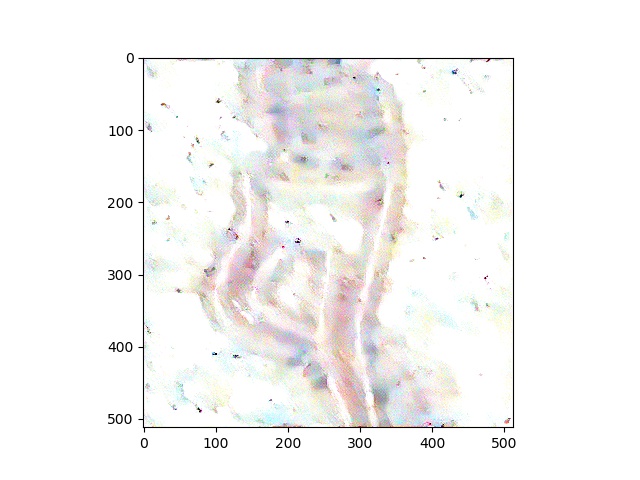

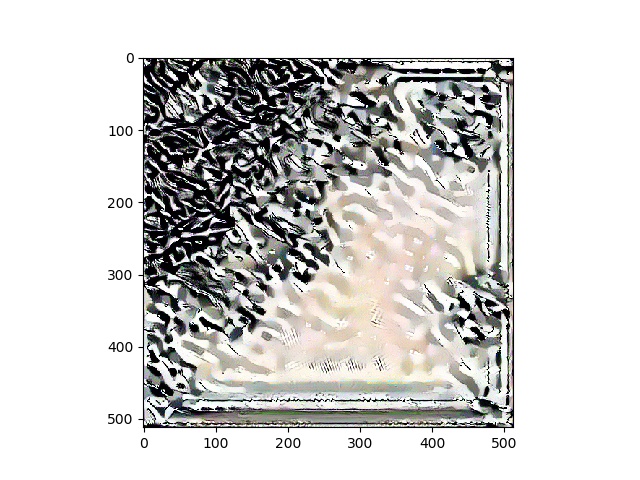

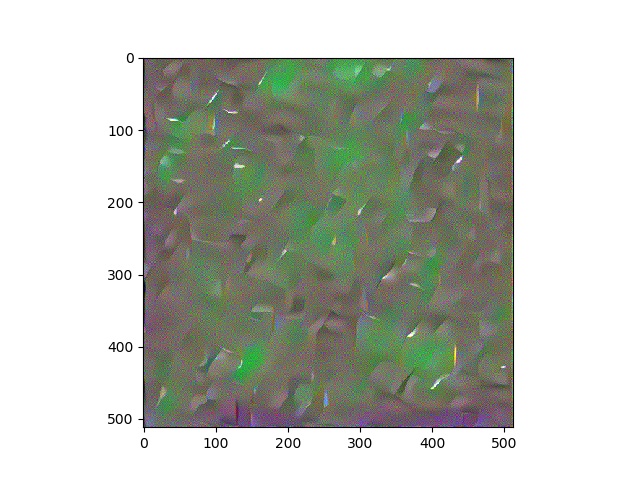

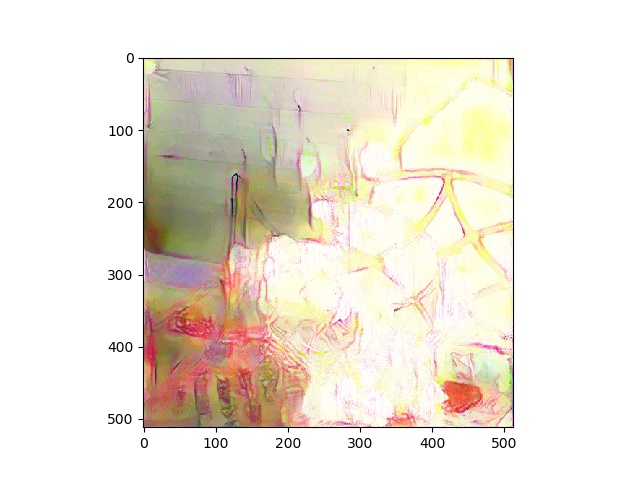

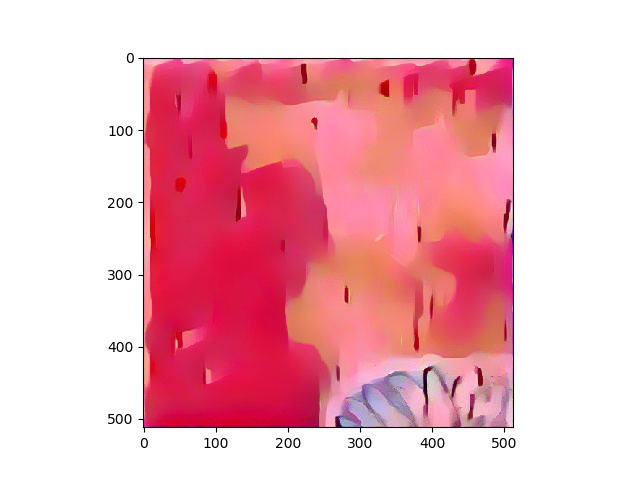

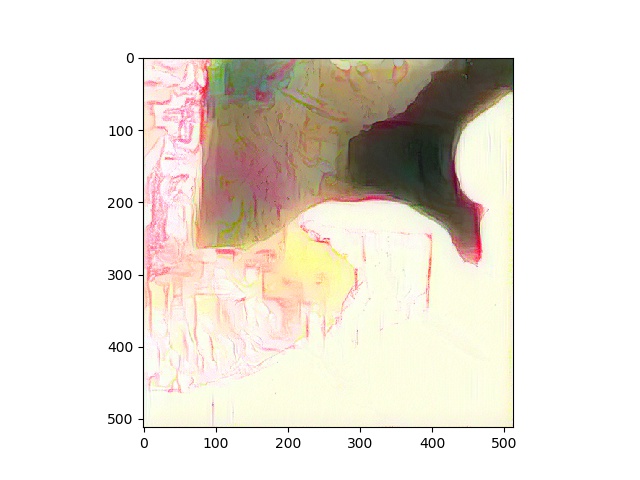

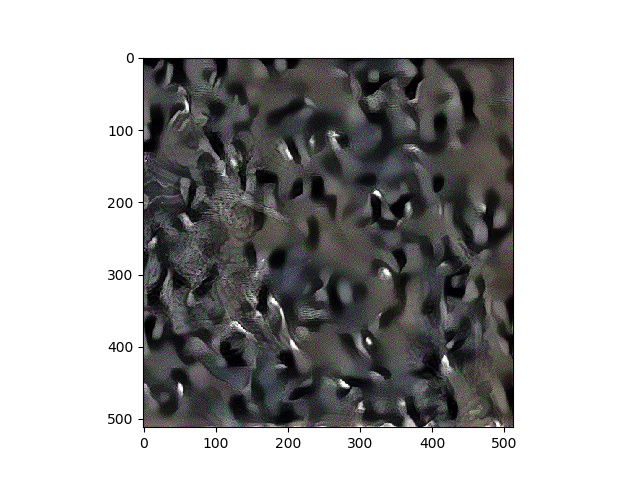

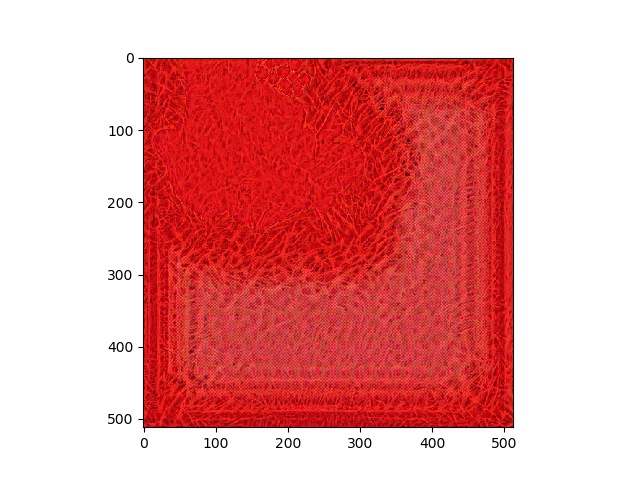

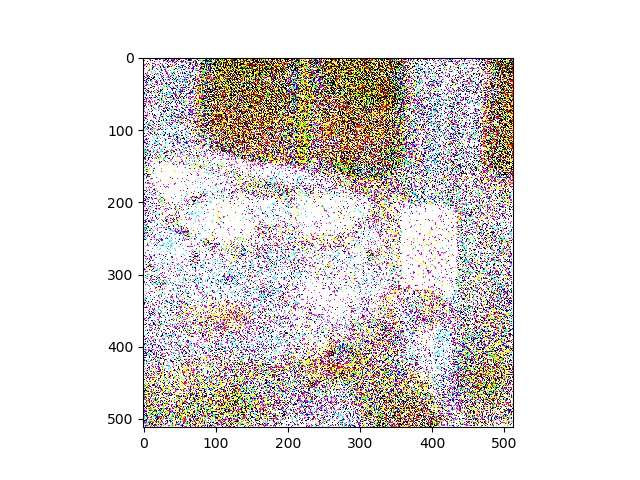

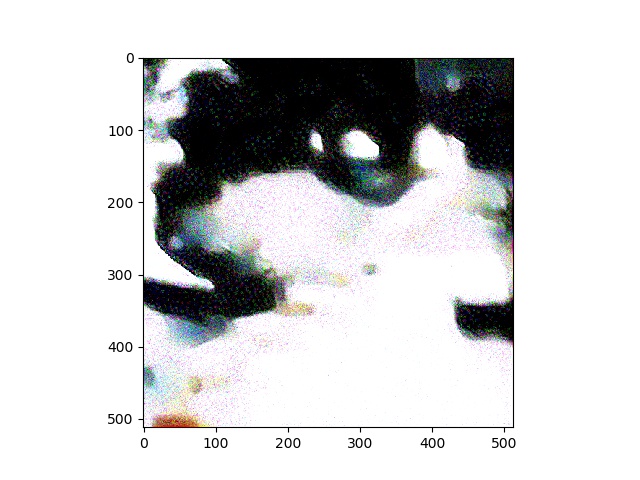

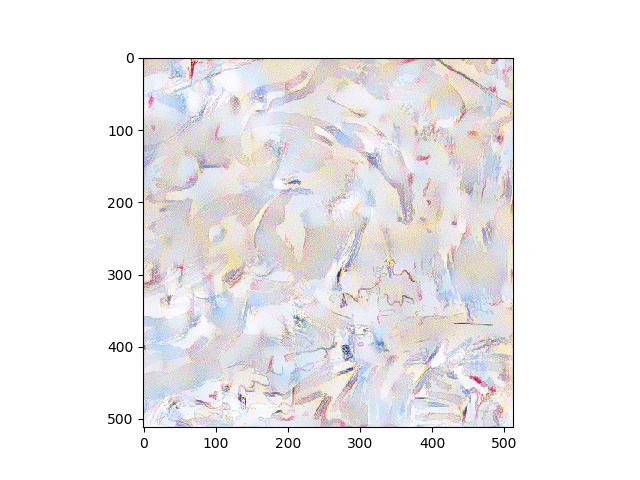

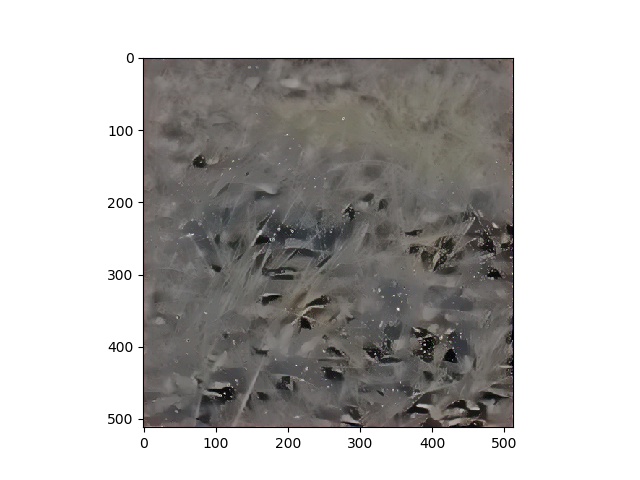

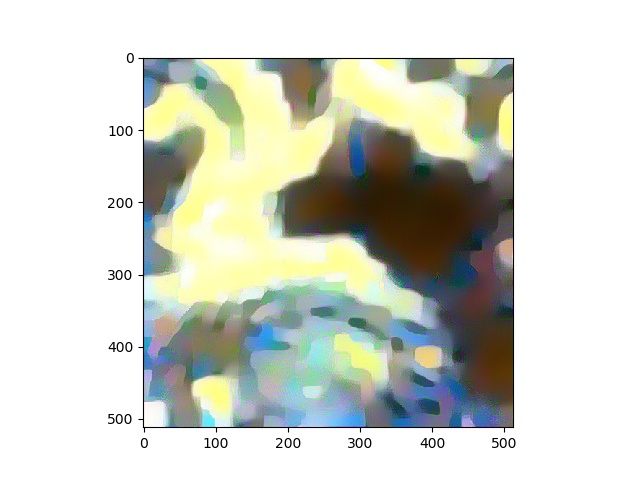

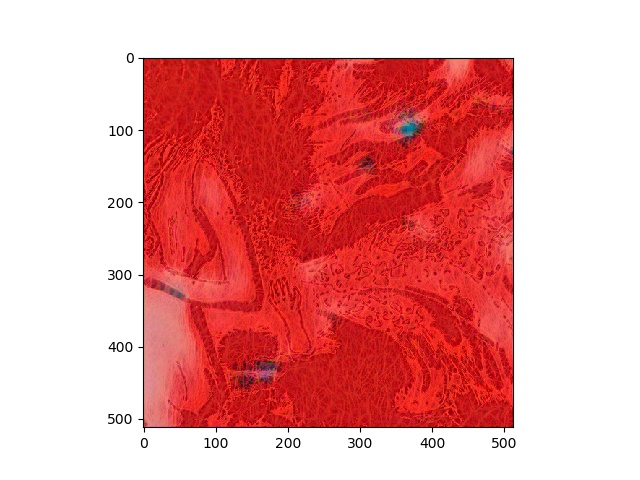

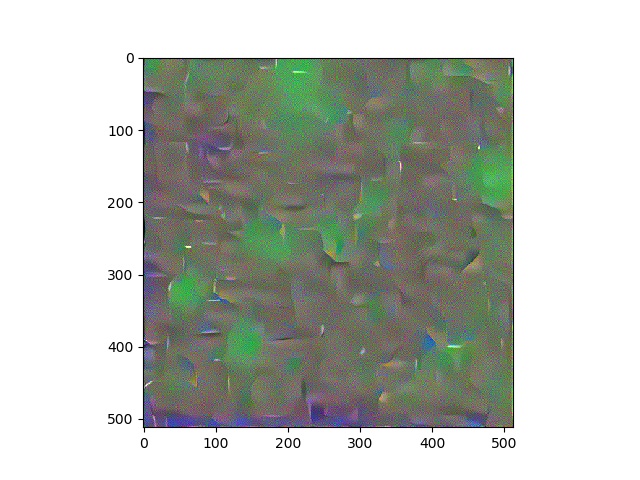

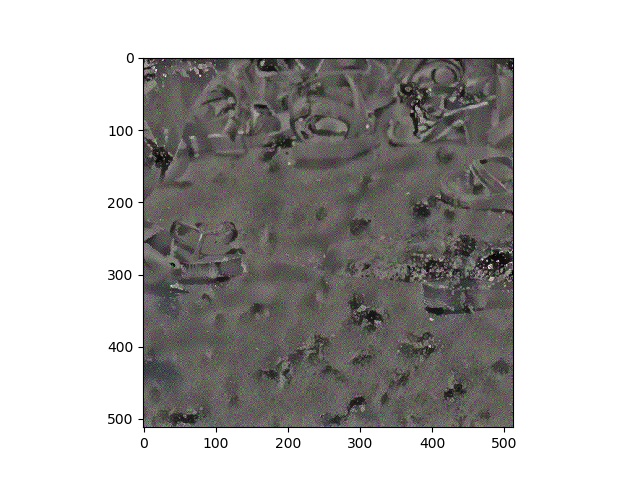

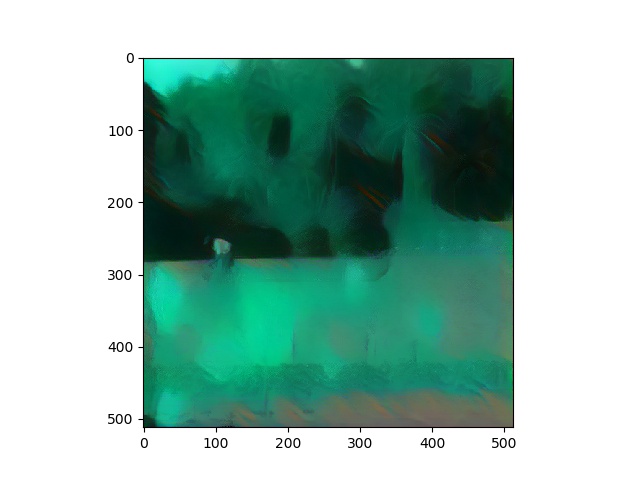

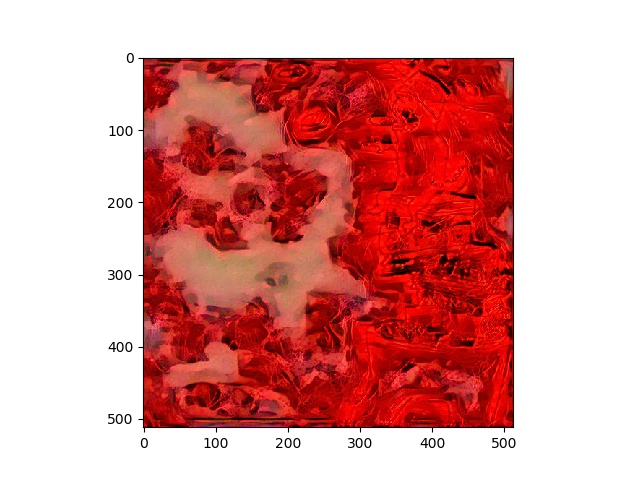

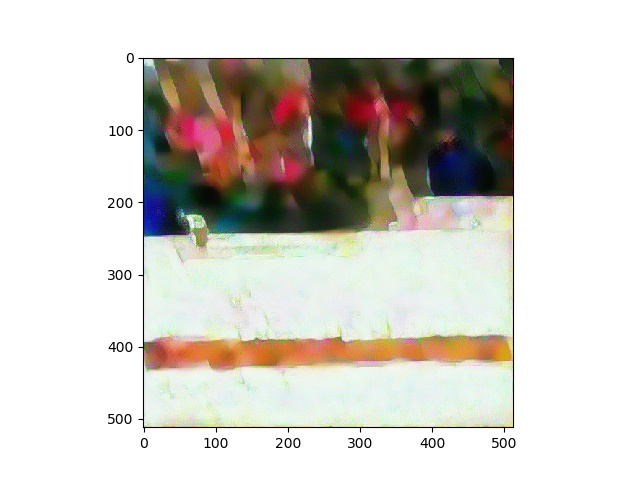

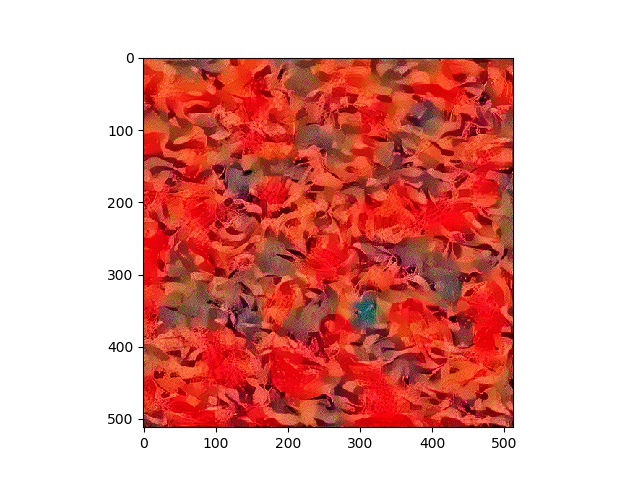

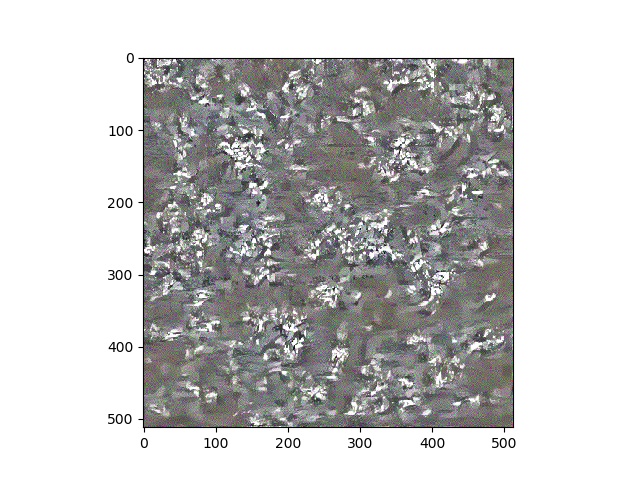

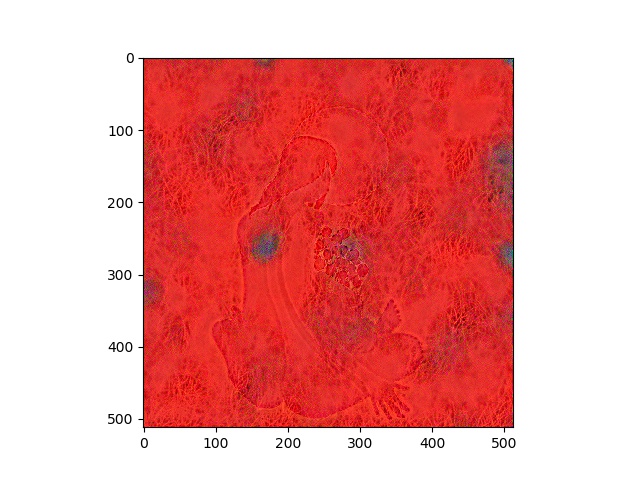

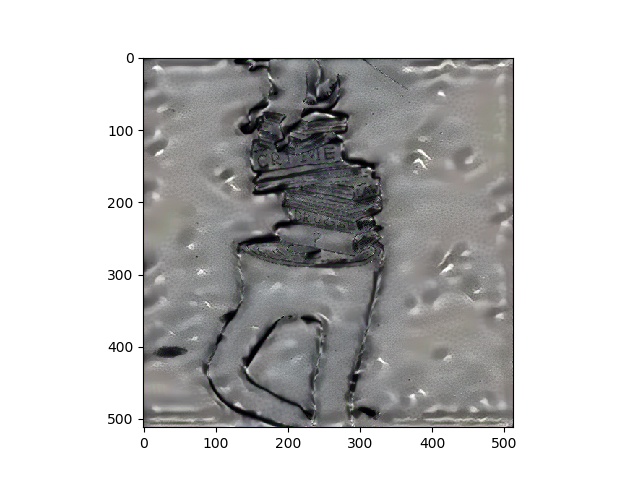

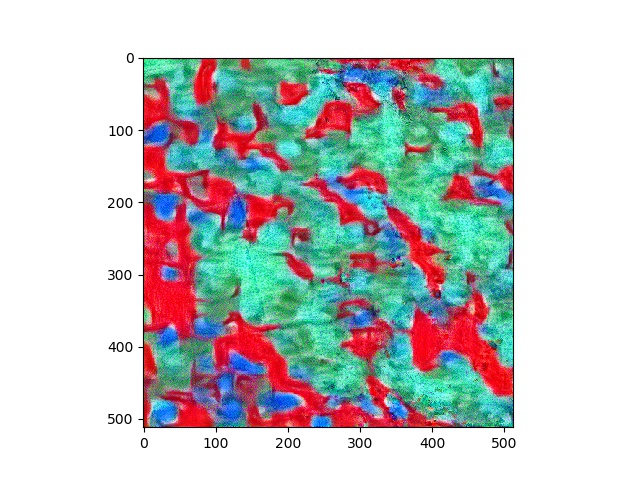

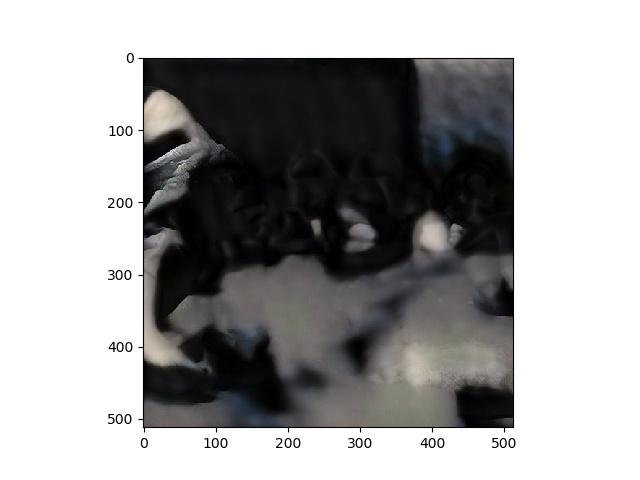

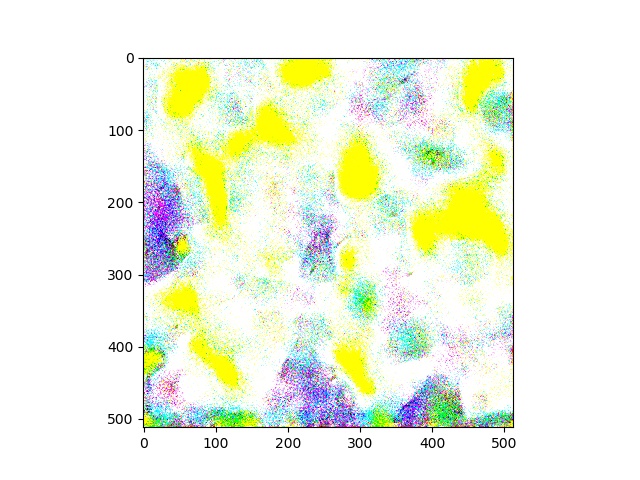

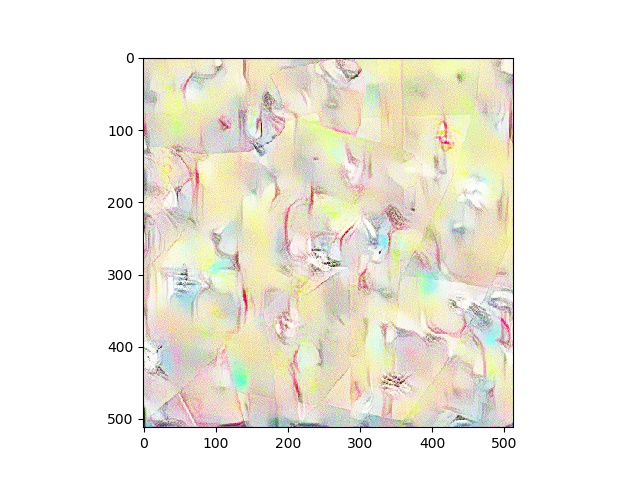

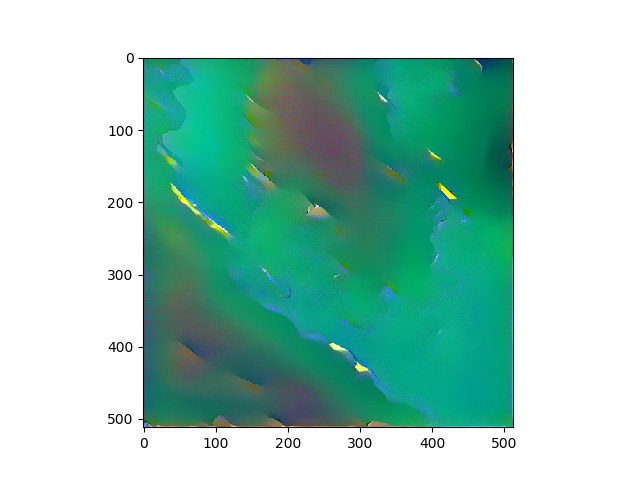

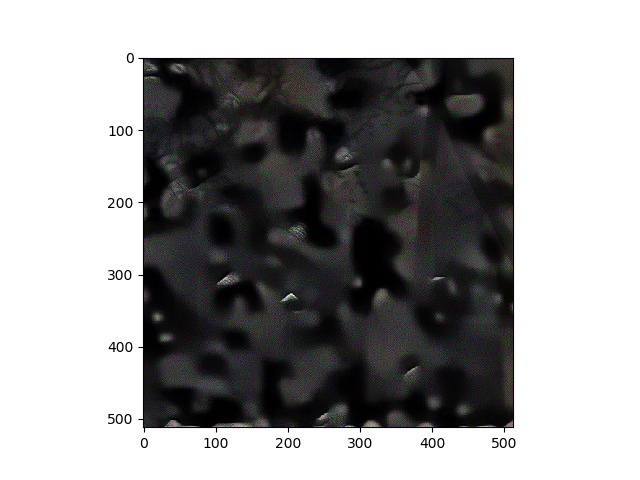

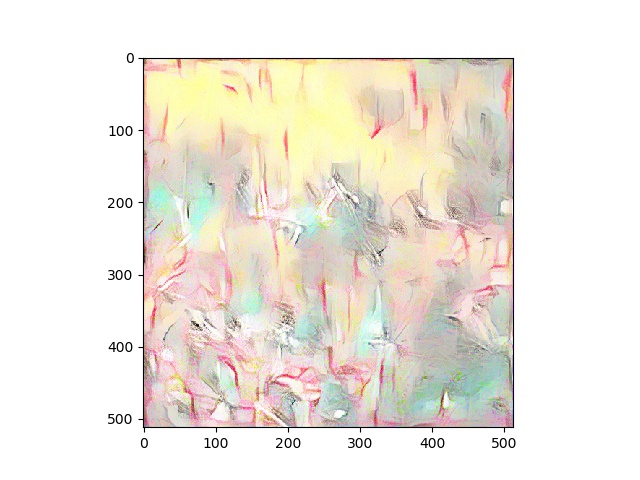

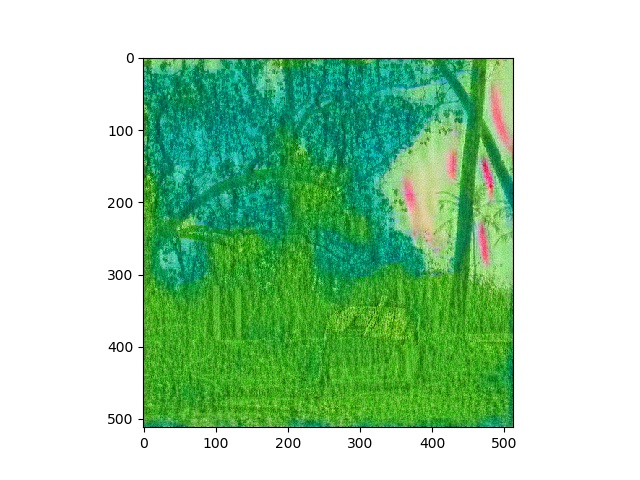

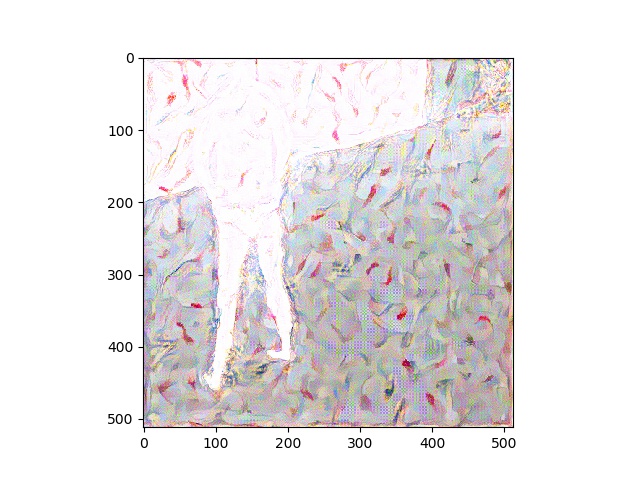

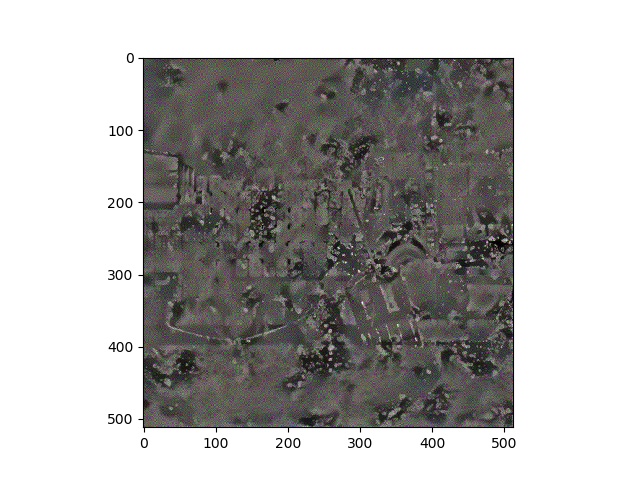

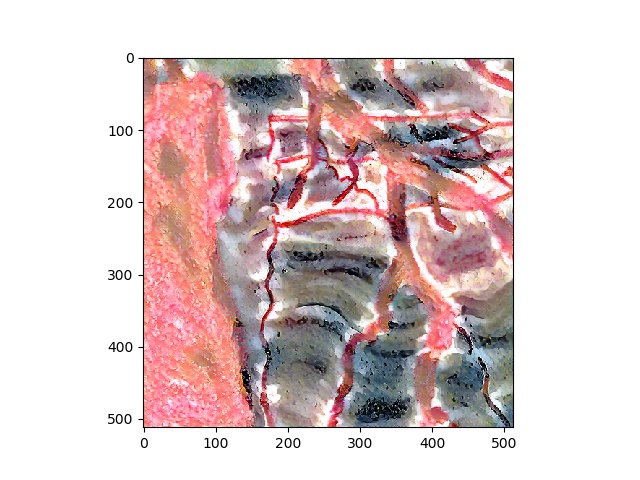

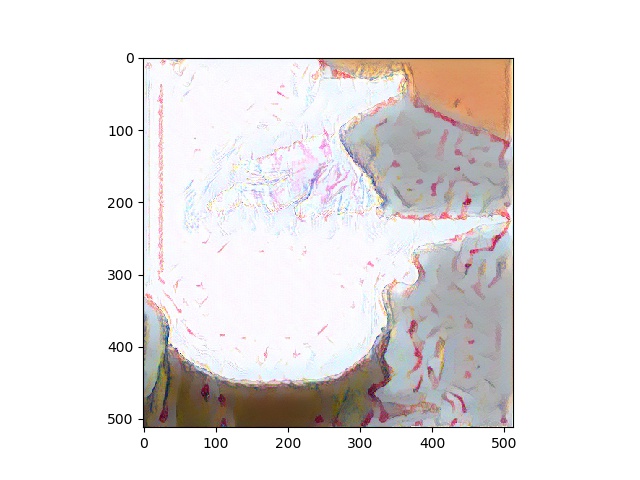

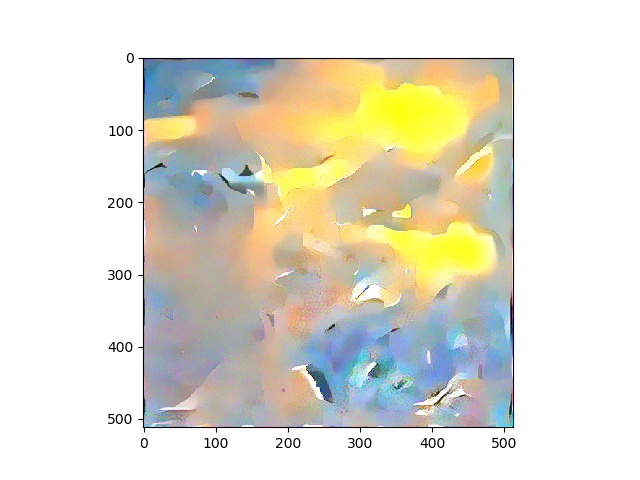

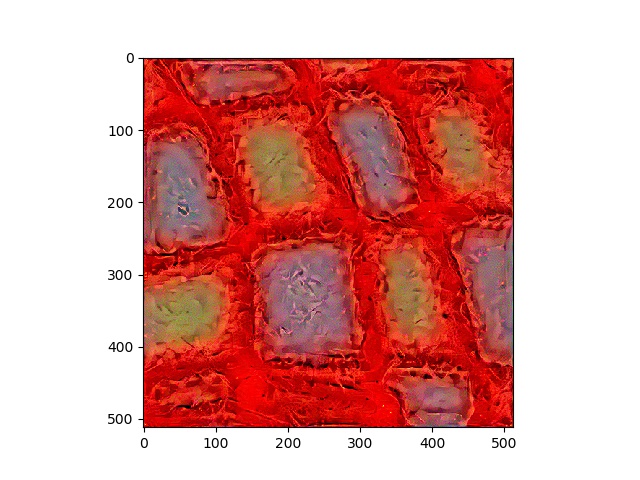

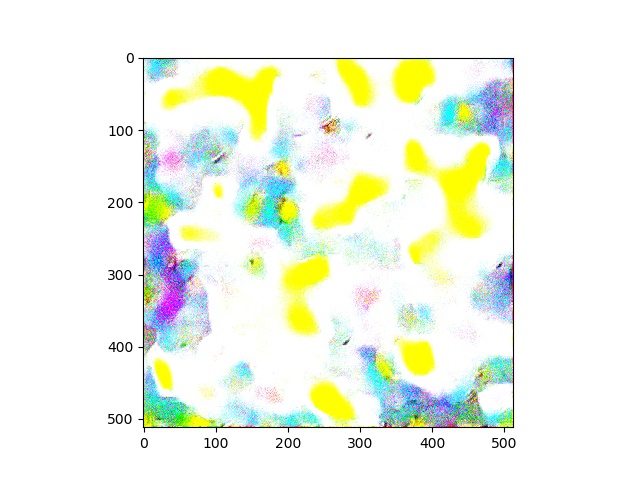

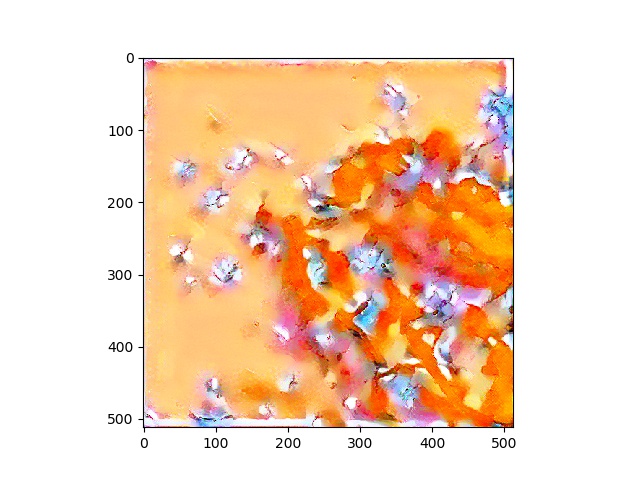

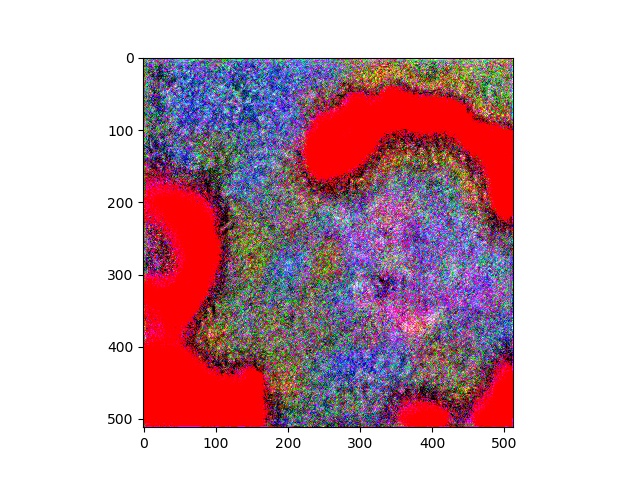

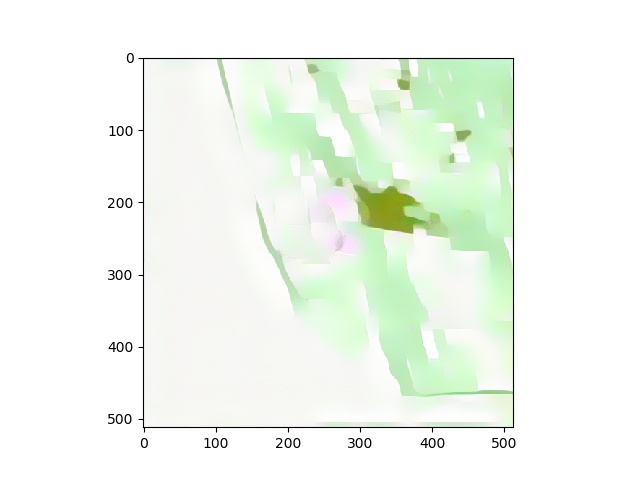

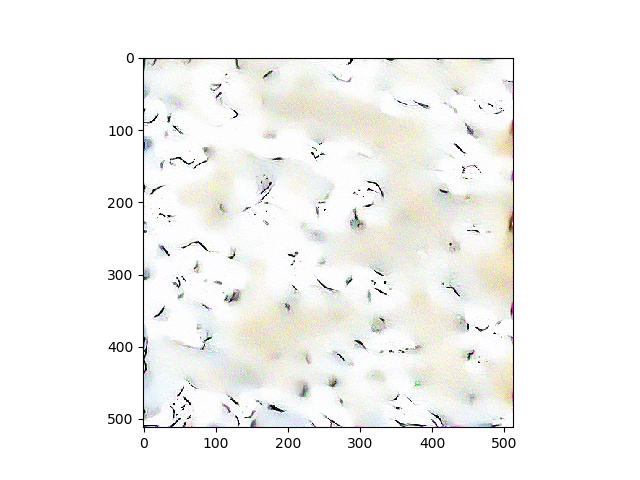

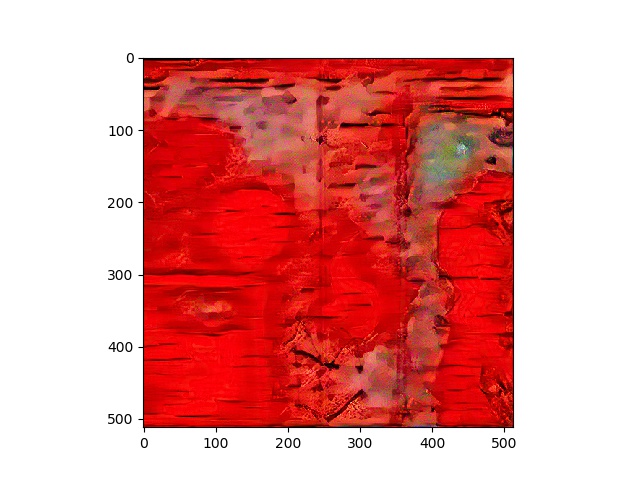

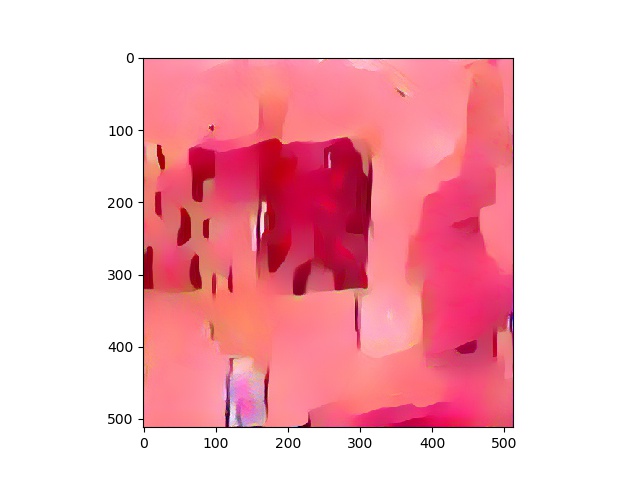

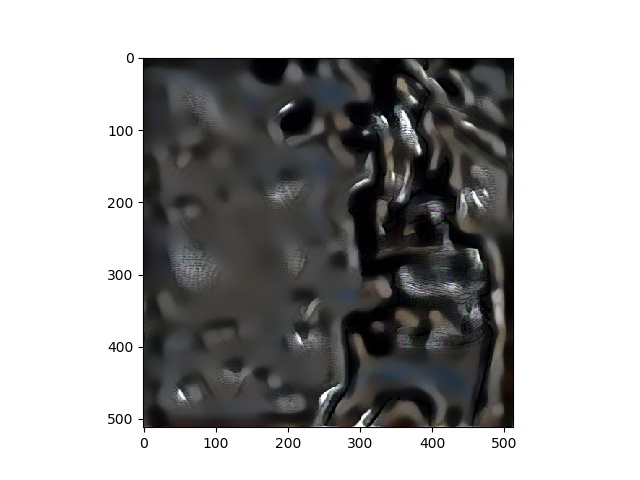

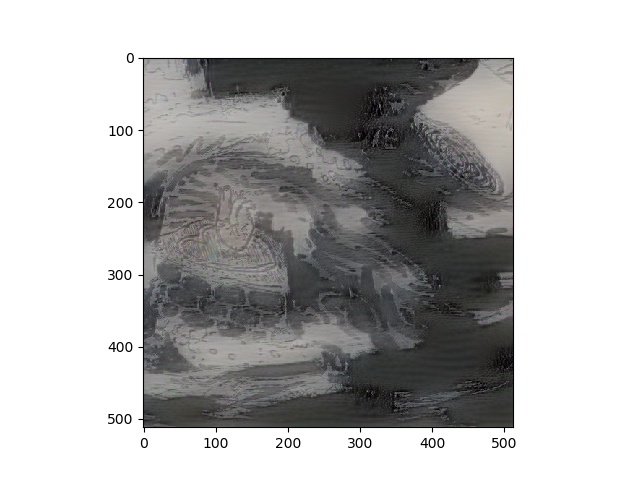

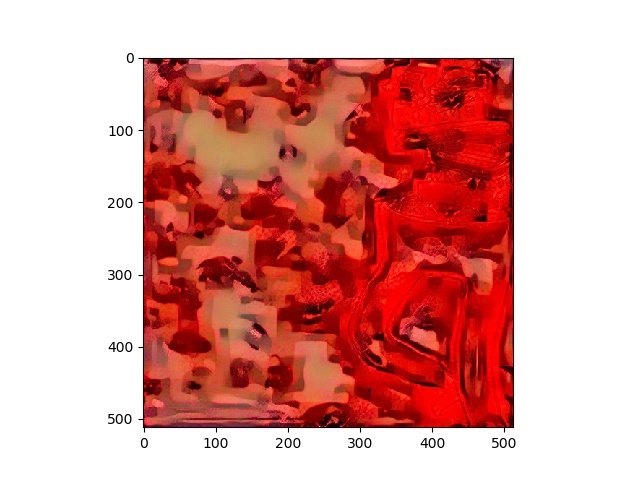

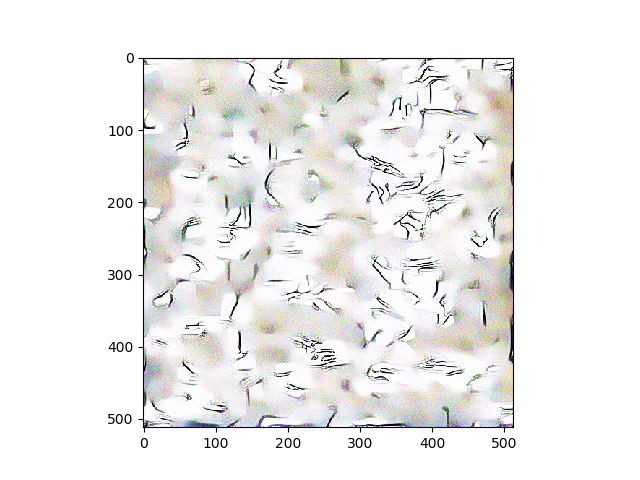

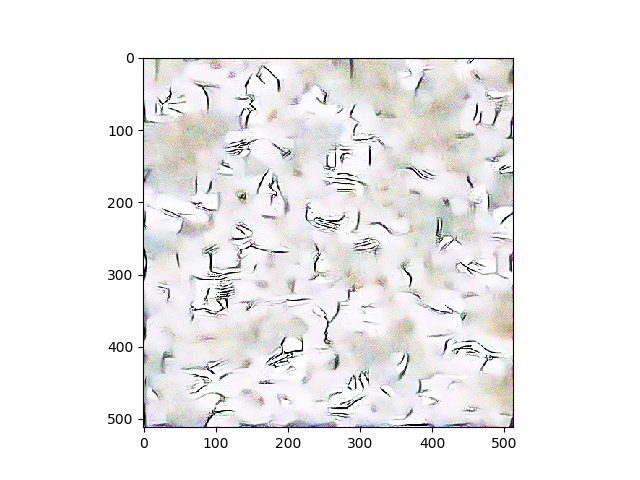

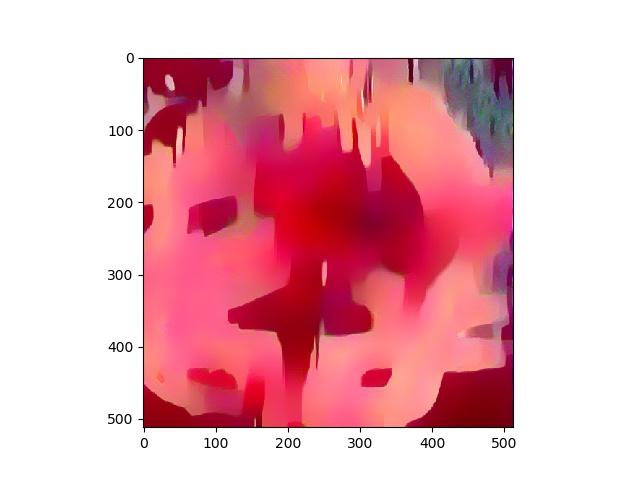

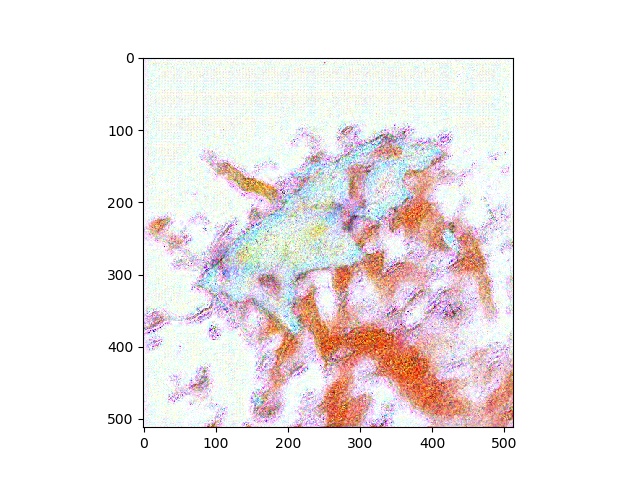

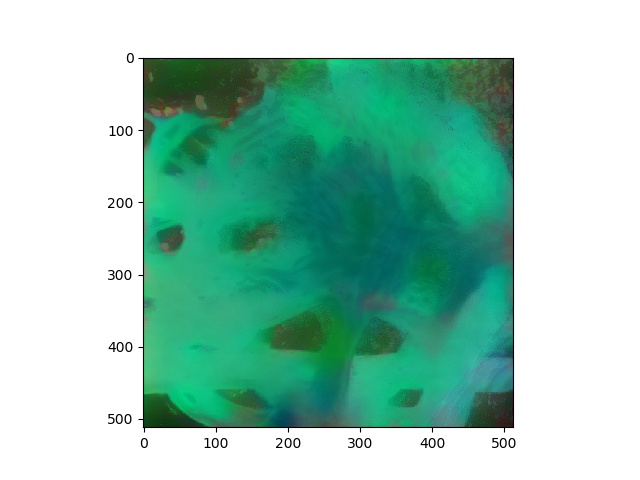

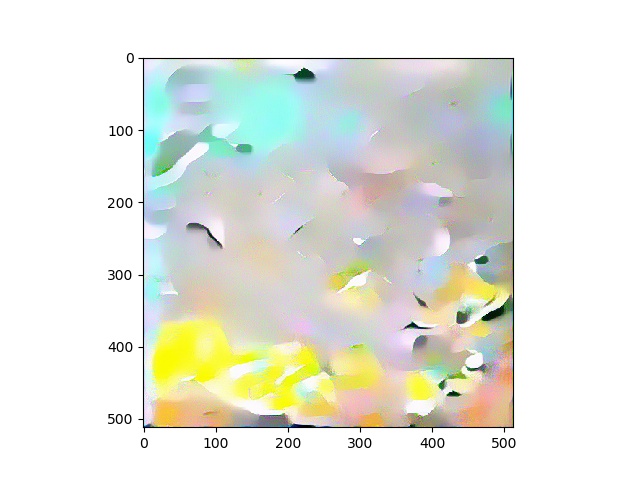

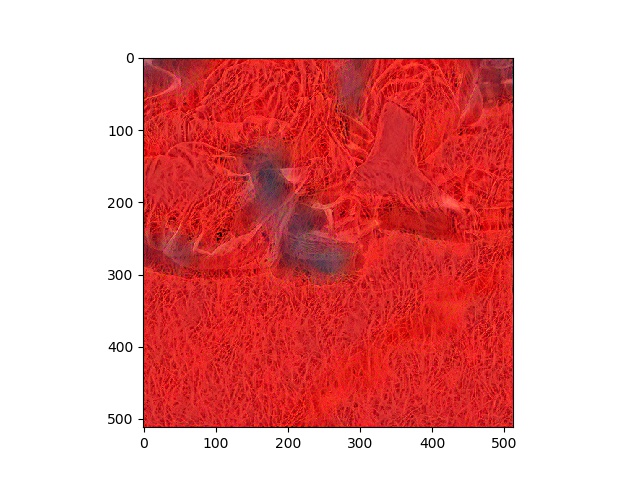

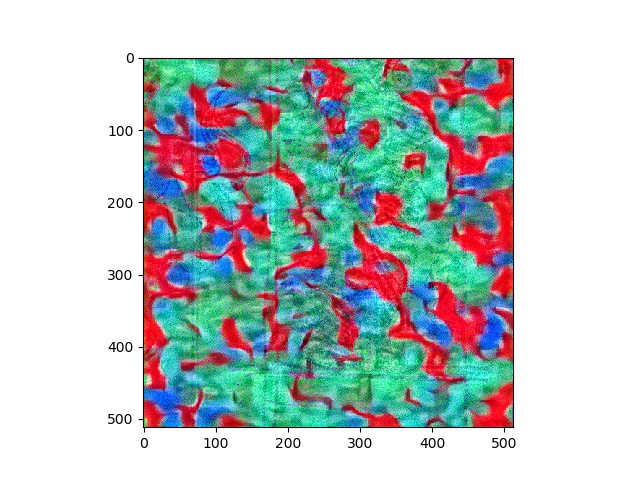

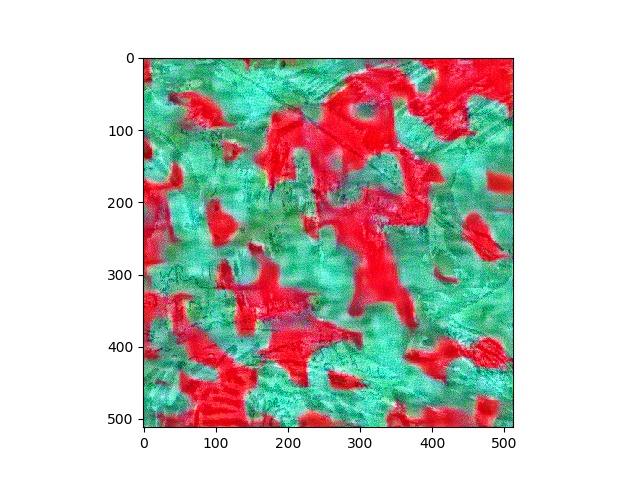

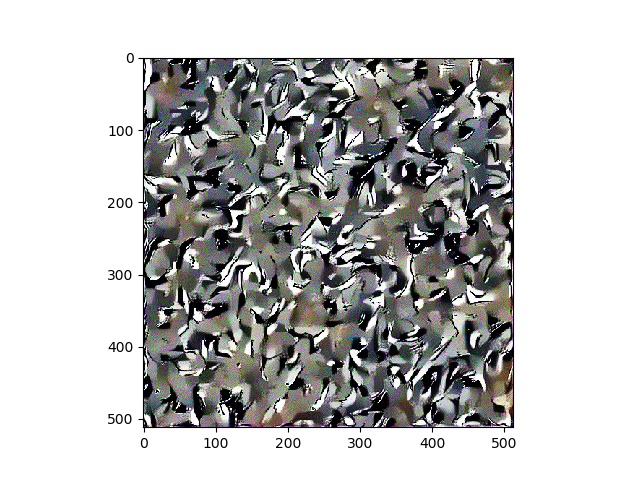

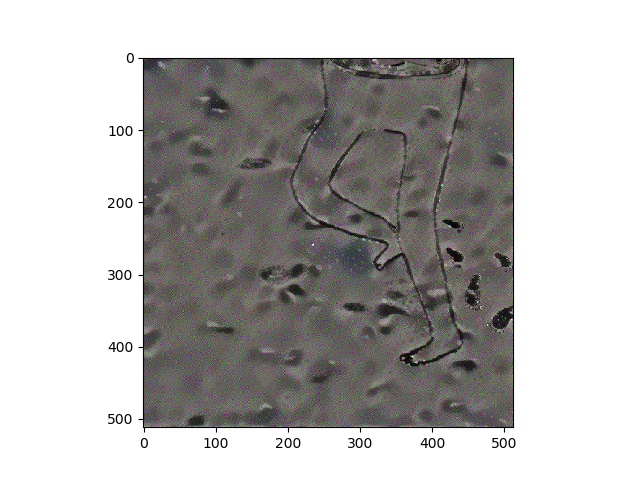

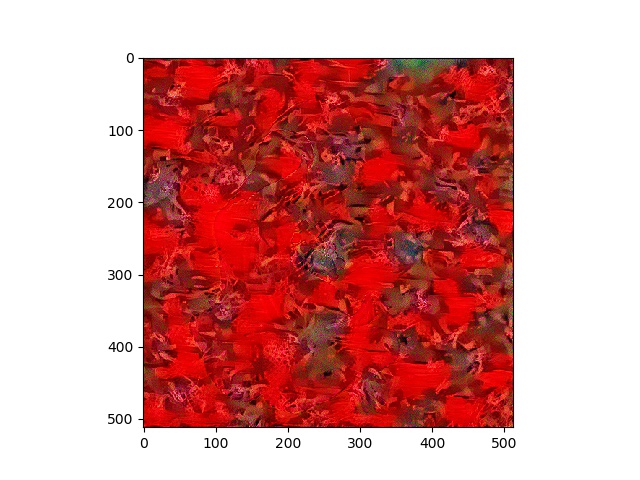

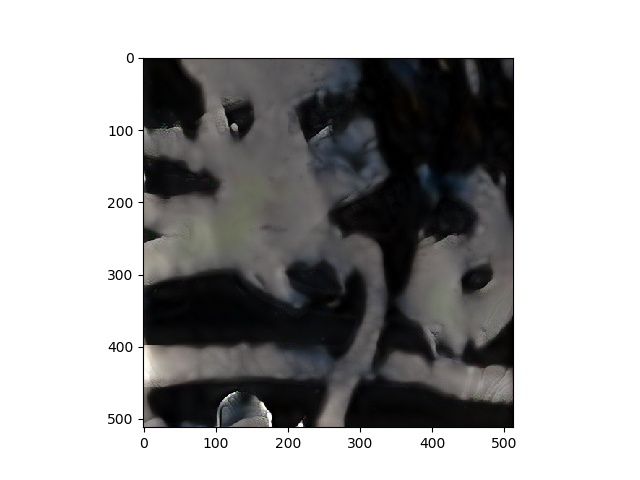

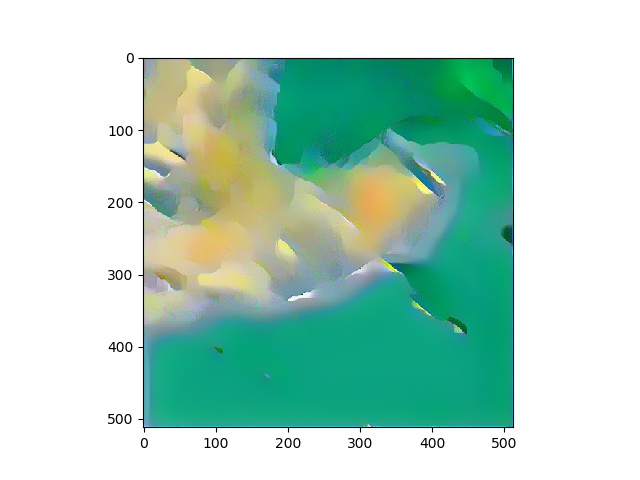

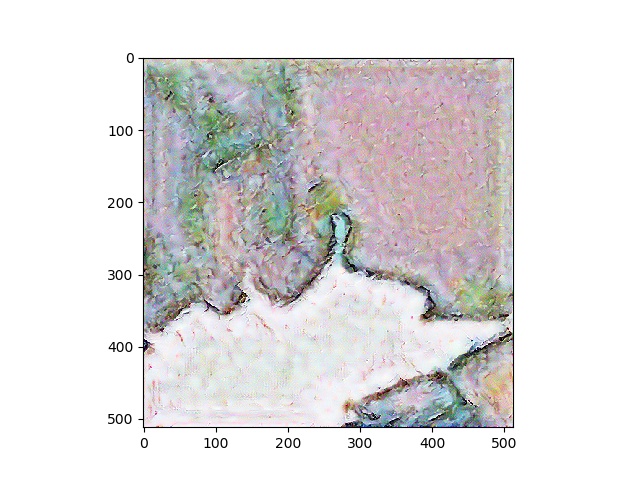

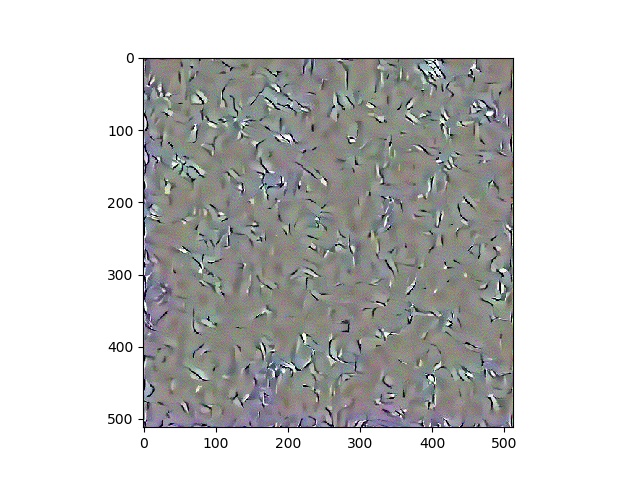

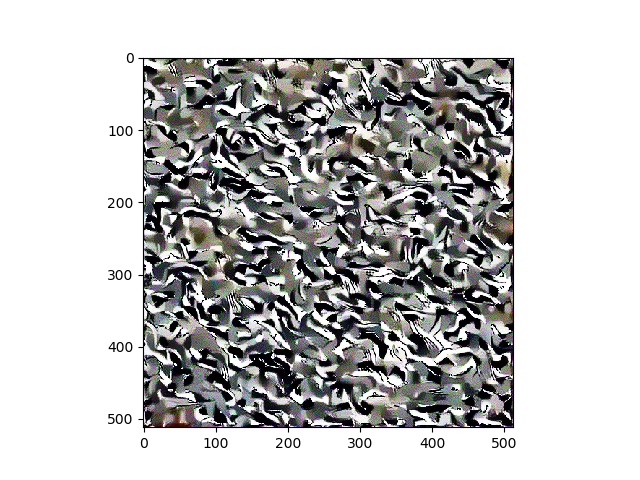

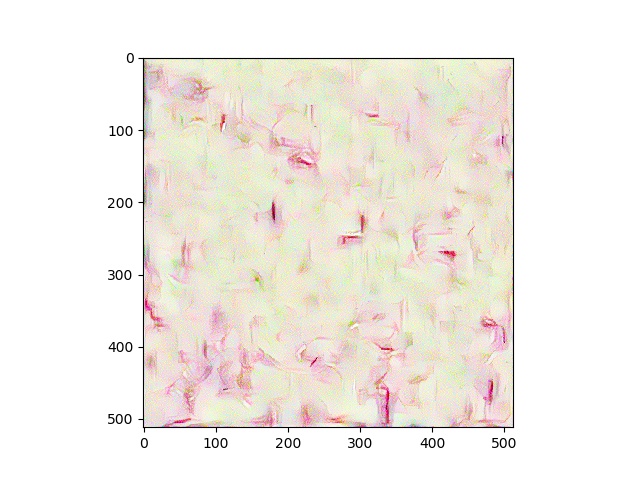

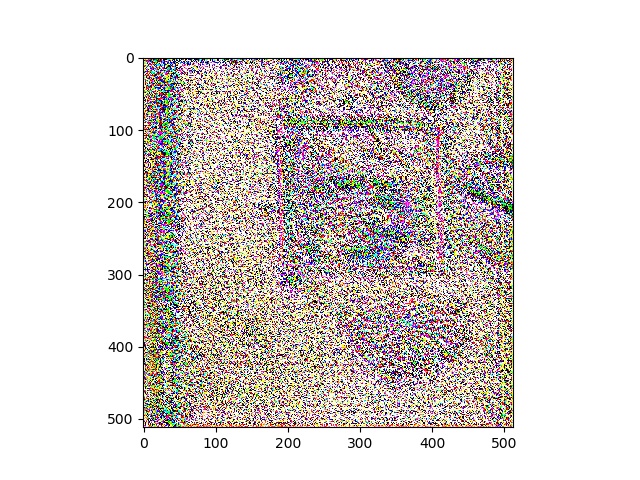

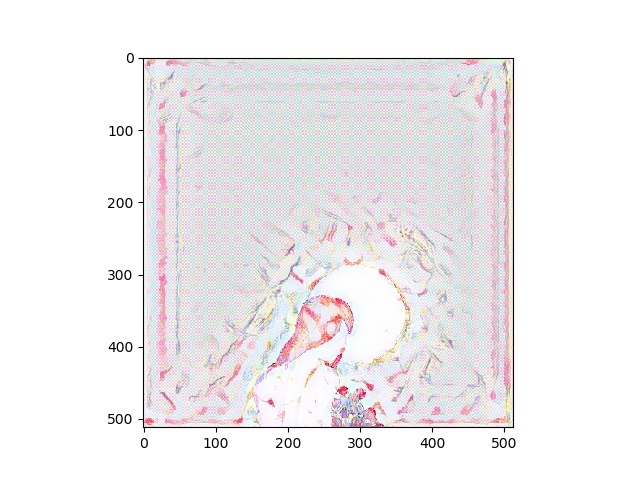

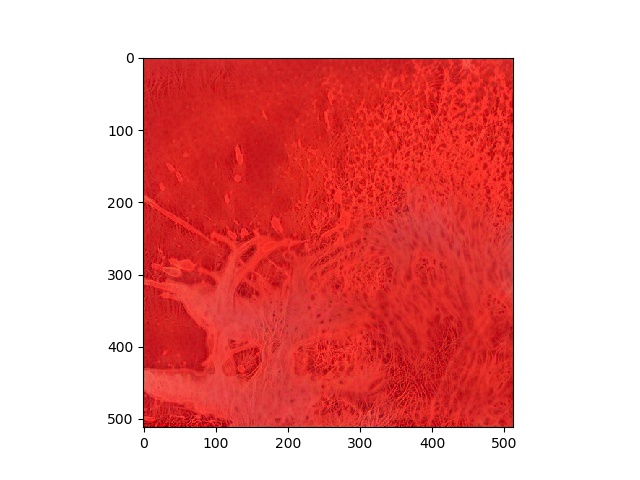

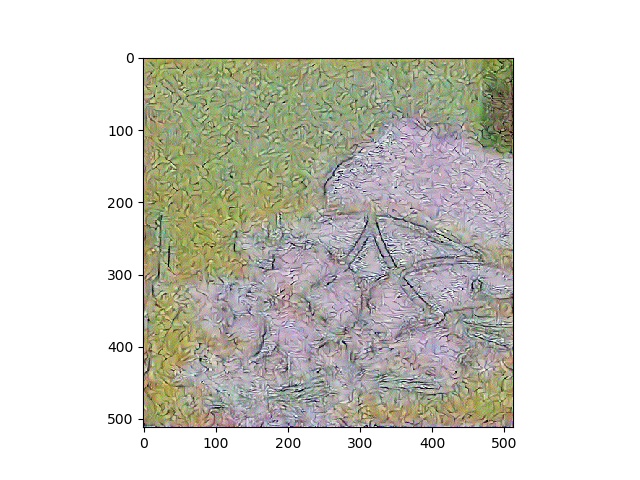

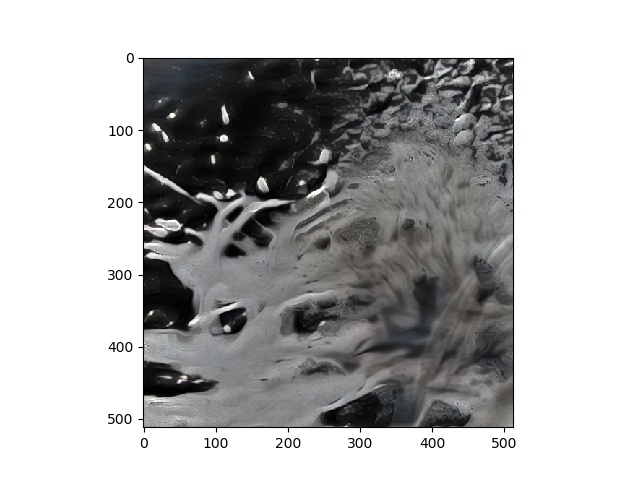

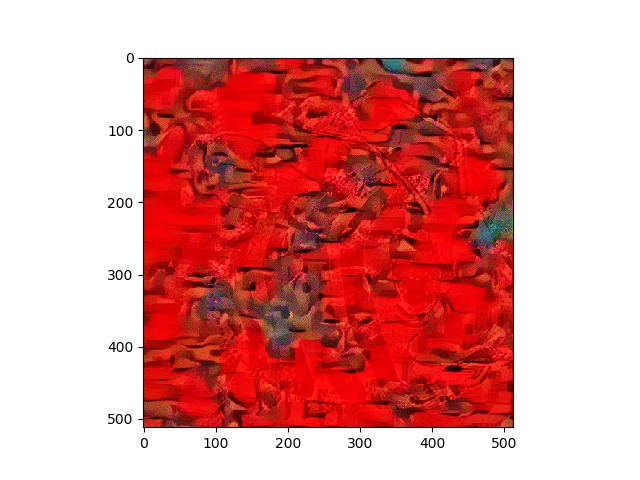

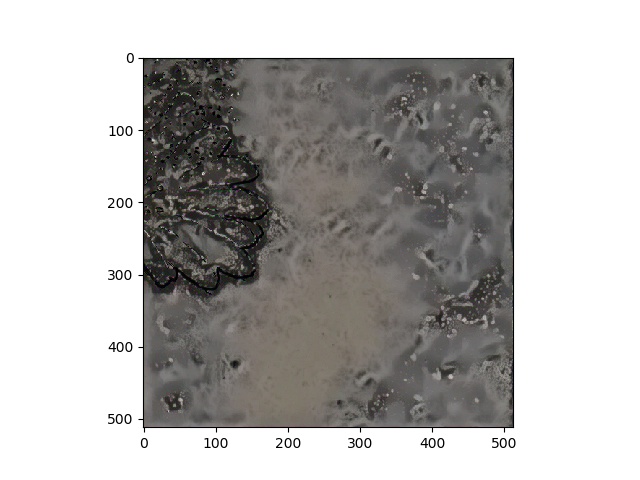

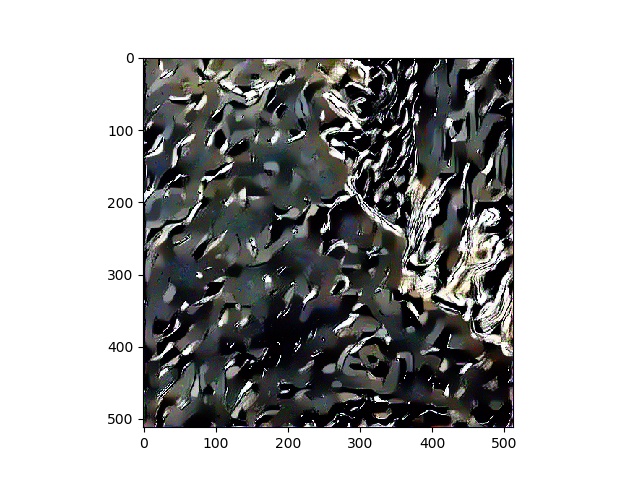

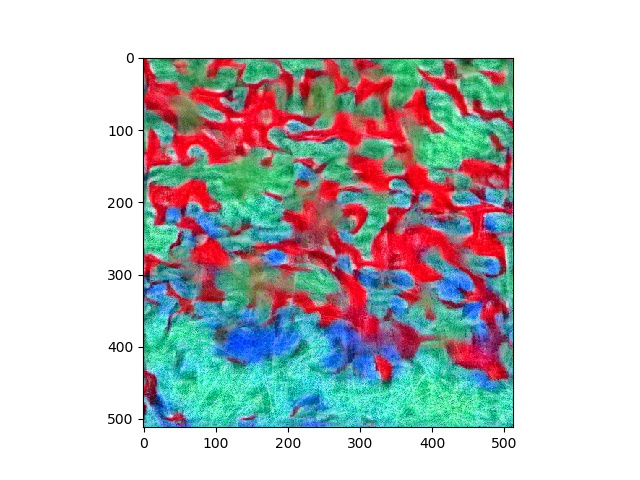

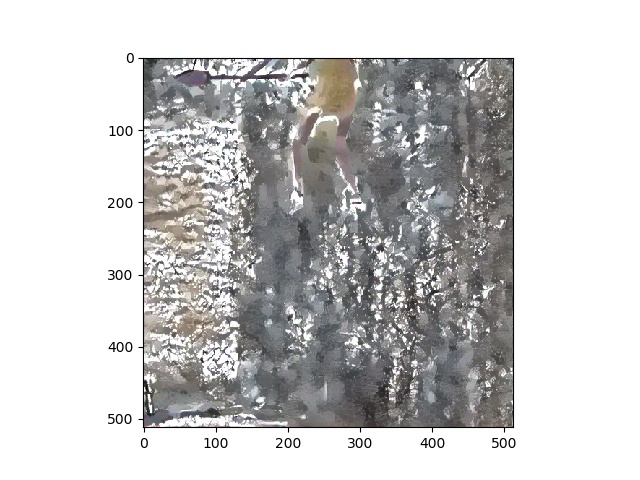

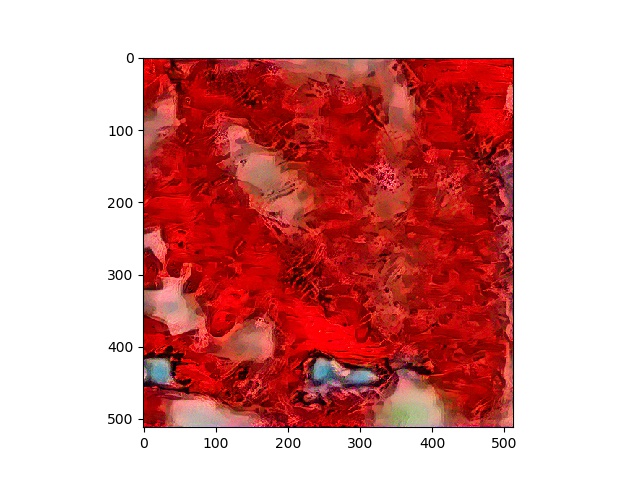

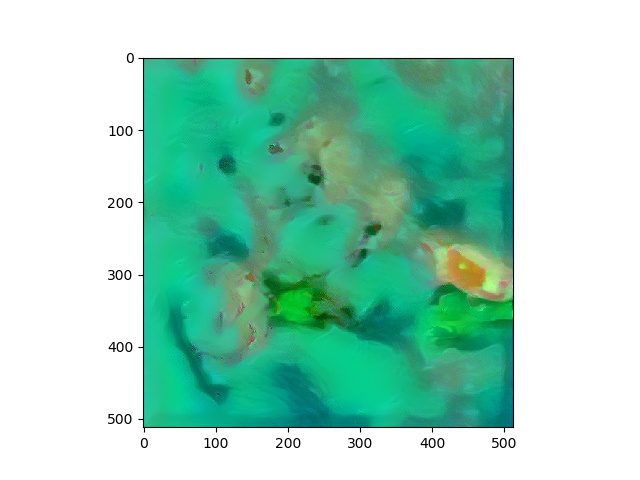

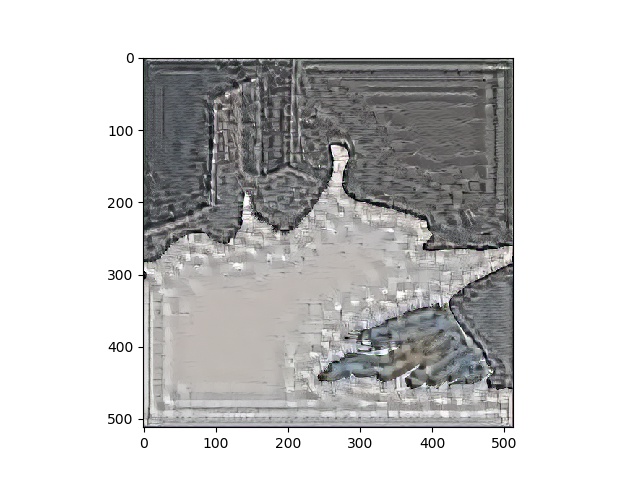

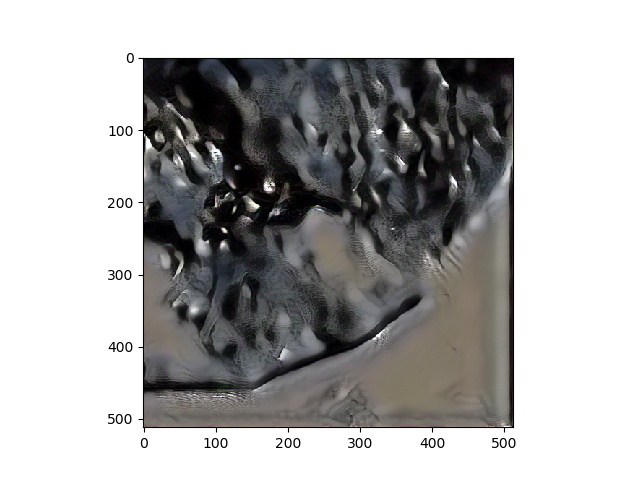

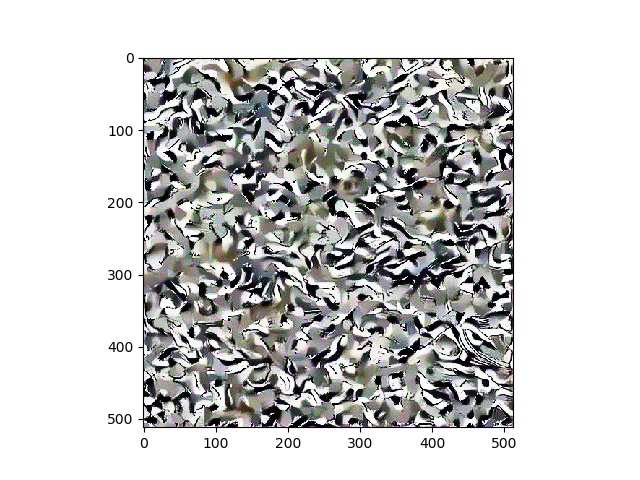

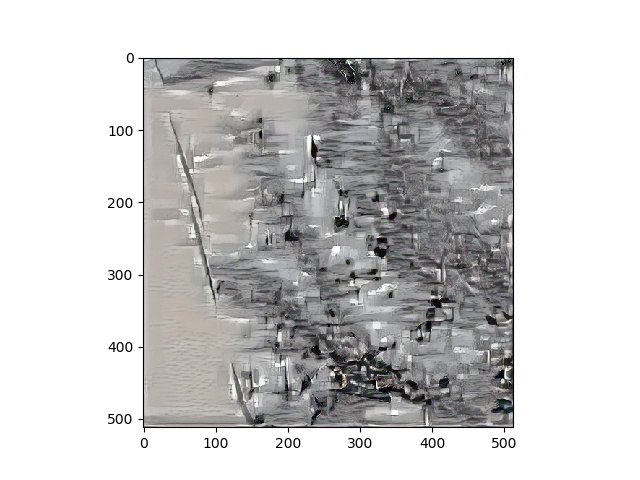

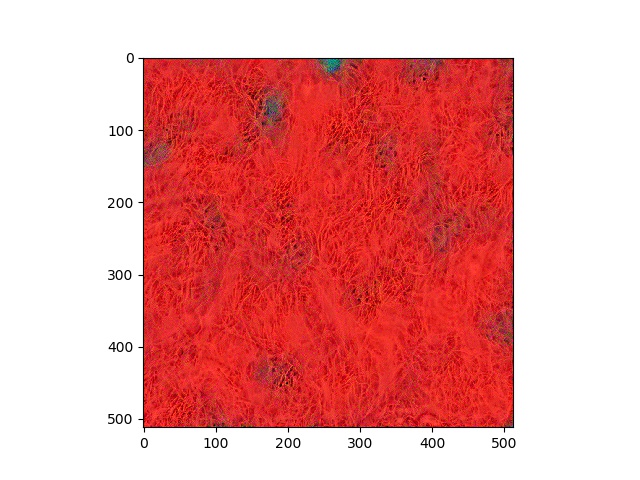

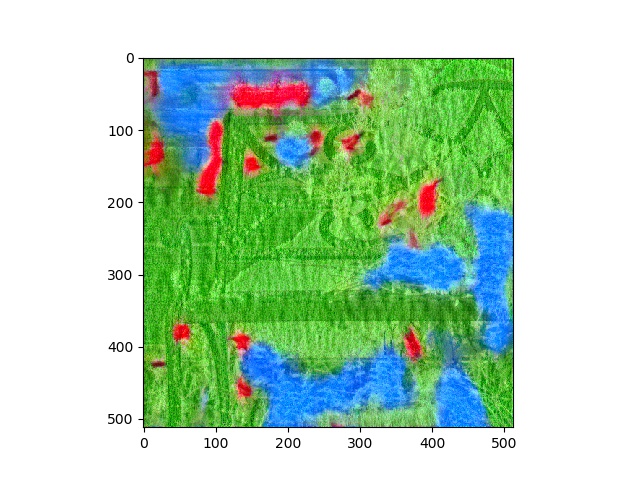

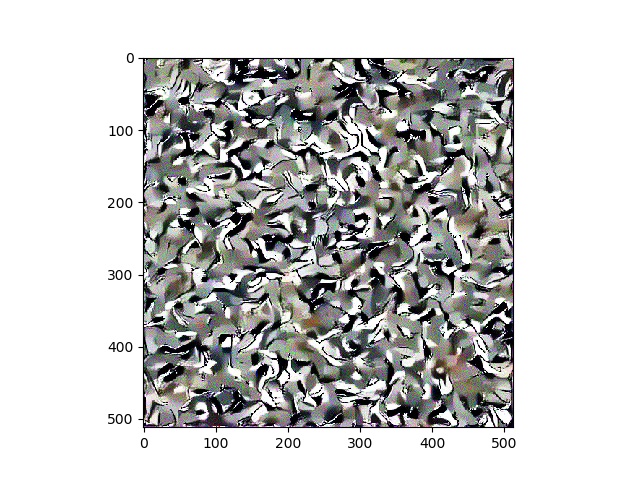

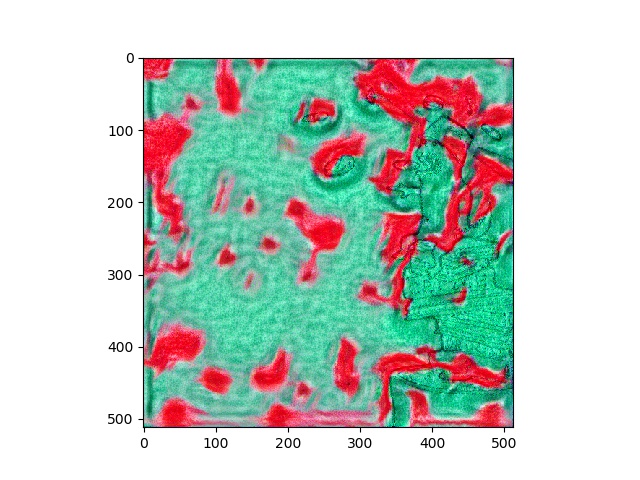

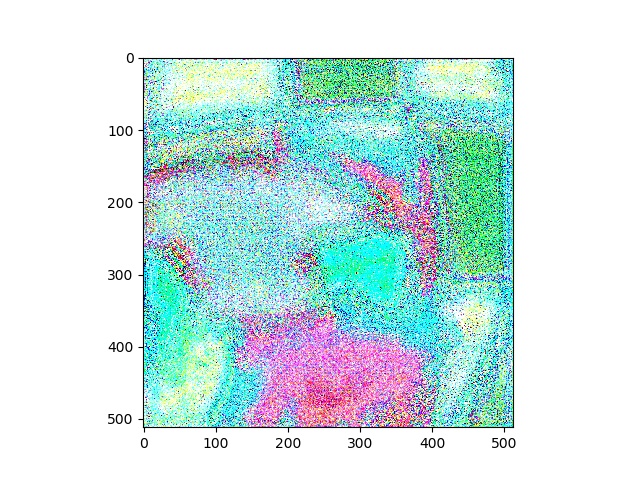

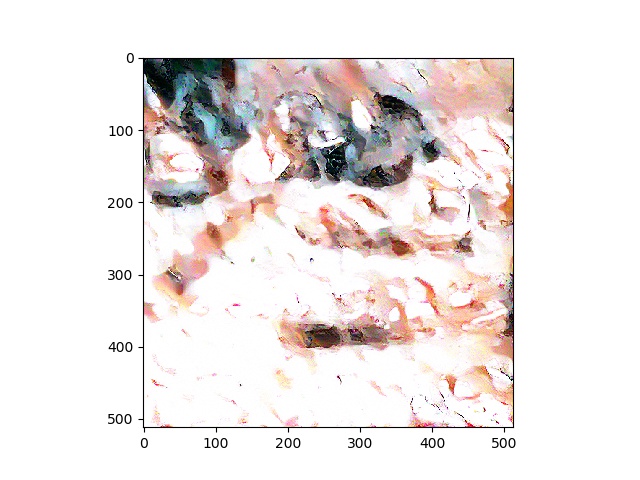

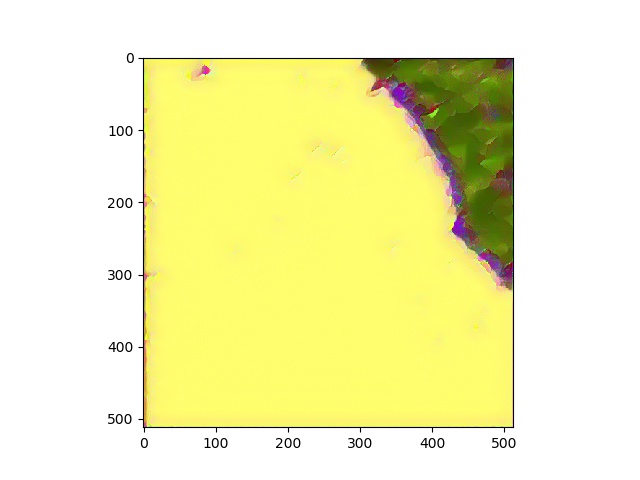

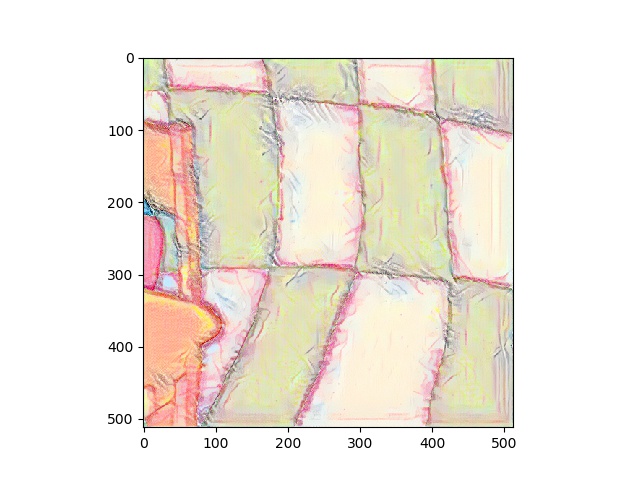

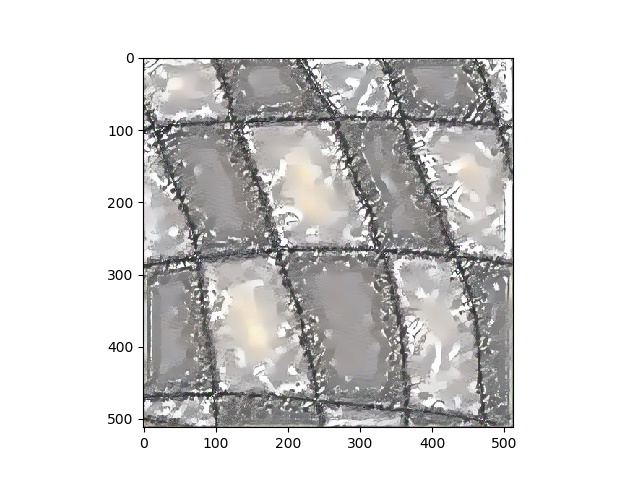

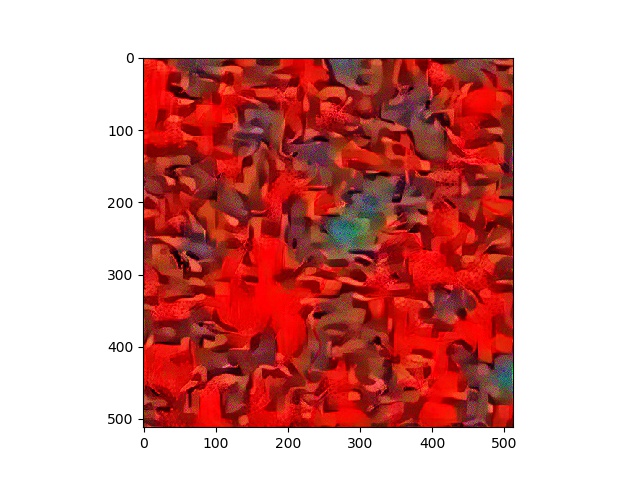

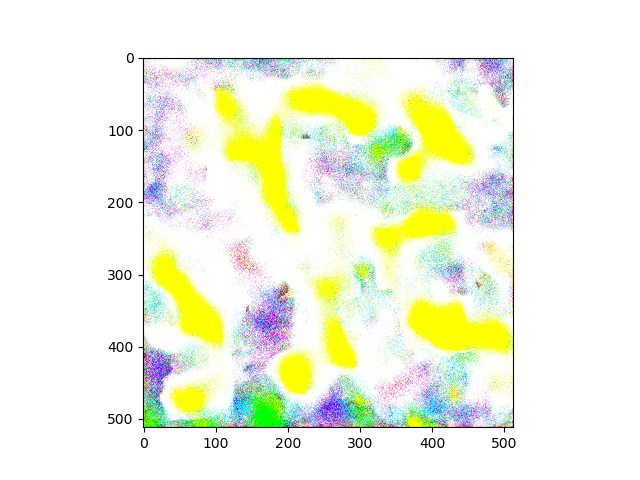

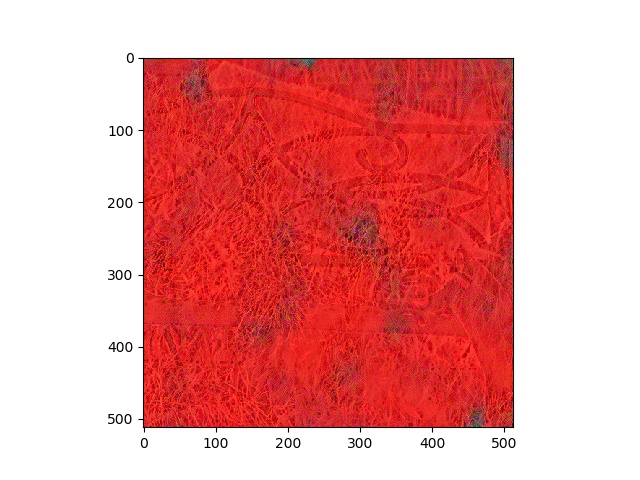

The first batch of images are waiting for me, the script is still running. I’m impressed by the novelty of what it has done to my old portfolio, which I had been feeling somewhat uninspired about.

But my shallow reverence of the programs perceived affect on my original intent sparks the first key principle I wish to point to:

Since we expand both technology and culture to understand our world, a good place to start this journey would be The World. Markus Gabriel posits that if existence is appearance in a field of sense, and if the world is the totality of things (the field of sense in which all other fields of sense appear), the world cannot exist. This is because, if the world is a field of sense such that it can contain other fields of sense, we must ask ourselves: which field of sense does the world belong to? While this paradox poses that the world does not exist, implicit in its revelation is the reification of all things, and the multitude of fields of sense which they appear. If the world is the totality of things, the world cannot exist. This being the case points back to the existence of everything for which we presumed the requirement of a world to contain them. (Gabriel, 2017) So, continuing with our invocation of Focault’s insights, let’s entertain that measuring how impressive a technology seems is rooted in investment of power. (Foucault, 1980) The technology spits out paintings, and my first instinct is to be impressed. Being honest, this is not so different from wondering how much of ‘the art world’ my work might make an impression on. So here is where the first adjustment of my thinking comes in.

There is no ‘world’ (totality of things) to measure acquisitiveness against.

In this light, a potential for new metrics of value now exists through the lifestyles artists now find themselves in. I suggest that we artists can stop resenting our corporeal dislocation from the direct physical act of mark making, and focus on something more compelling: our thoughts.

Continuing with Gabriels observations, also important is the idea that art’s purpose has always been to afford us our understanding of the ambivalence of sense. (Gabriel, 2017) What does this mean to us here? It is crucial to see that objects can appear to us in many different fields of sense, and that when something reveals itself to us, we needn't necessarily perceive how an object is given to our sense to believe that we have gleamed objective insights from the objects’ appearance. The revelation that this presumptuousness is in fact objective and observable is what the powerful will use to exploit our intentions as creative individuals.

“We try to understand everything from climate change to biotechnology. But we can only process that information through the lens of our intimate selves. We interpret the world by way of our personal needs and desires, and so we are vulnerable to larger powers who know how to speak to those needs” (Thompson, 2018)

Even art we have relinquished our ‘hand’ in will have implications implicit in its exploitation for political agendas. We must be mindful of how technology refigures us before we consider how we shape it, or worse, allow ourselves the mistake of considering it to already be refiguring itself without us. We need to closely watch the stories we are telling ourselves about technology we don’t yet ubiquitously understand, because how we choose move forward with these figurations will have heavy consequence on how much of the freedom which affords us with tools like ‘AI’ we get to keep.

Back to the beach. I envision this becoming routine one day, and wonder where I need to be as a ‘painter’ when a machine paints for itself.

Let's zoom in a bit, from a totality of things to the totality with which our image of things is given to us.

The image is not in the mind. It is a relation of the mind, given to us amidst many types of consciousnesses. Just as there cannot be a world containing all things, there cannot be an image which contains all of a thing. We tend to endow prescience to the veracity our images of objects. The perceived totality with which our image of something appears to us is often conflated a with falsely concrete, ‘complete’ notion of the object despite it continually revealing new facets to our perception. It is important to understand that our notion or image of anything is only the sum of observations that have been given to us, and that there is always more observation that a subject can give to our image of it. In short, the totality of your observations will never equate to a totality of their subject. (Sartre, 2010)

Where the intersection of art and technology influences our thinking, Sartre's notion of the image affords more communicative power to a creative technologist. To understand that something is revealed to us iteratively by the nature of our perception frees us to learn without getting in our own way. Creative technologists embracing this philosophy of their perception could perhaps even come to circumvent the typical experience of imposter syndrome. This would surely engender a faster progression toward the voices of creatives making more direct contributions to the constructive refiguration of emergent technologies themselves, and therefore would also allow a more natural progression toward a true ubiquity of software tools.

Sat on the beach, dislocated from my practice while the act of painting, imagining the act of painting to propagate itself, an insecurity surrounding a conflation of virtuosity and value bubbles to the surface. But:

If we can dispel the myth of an object conjured to imagination in concrete totality, we can dispel the myth of a genius’ vision. That something cannot appear to our imagination in totality simply frees us to think more clearly. And especially when it comes to discussing AI: I believe we are not thinking clearly.

There’s something I love about how matplotlib is framing my paintings in little graphs. I feel like it speaks to the messy relationship between culture and quantification present in art today.

It would be negligent to discuss an empowerment of creative thought to contribute to refiguration of tech without bringing up power. In particular, as this program makes images and I find myself more in the role of a spectator, and my agential role shifts away from manual action and toward curation and reflection, I am drawn to the notion of ‘the eye of power’. Foucault highlights the concept of the Panopticon. A prison in which the dynamic of the traditional dungeon is reversed. The principle is simple. Sheer visibility coupled with the presence of an overseer captures the inhabitants more effectively than darkness. This was not just an architectural solution specific to surveillance, it represented the great innovation of the simple exercise of power. (Foucault, 1980)

From Foucaults thinking, we can see clearly how our creative intent may be exploited through its need for visibility, and its aim to manipulate through stimulation. I think that most of all this shows that as creatives we need to be discussing whether it is our role to subvert these power dynamics gently, by reforming the public view of tech through demystification, or whether we need to weaponize ourselves and our practices, ‘to match the apparatus of the state’, so to speak. (Focault, 1980)

Because of how technologically oriented debate has already refigured our thinking, I feel that we will soon have to all make this call individually: do I weaponise my creative agenda, and pursue change of creative technologies on my own terms, or do I subvert this universal power struggle altogether, in favour of a slower, more stoic form of progress?

I keep referring to “the machine” painting. This feels kind of naive. I connected the pipeline, didn’t I?

Probably the most natural way to illustrate the widespread understanding of AI today would be for me to refer to it as a ghost. Suddenly we envision an extrinsic entity whose arbitrary and ambiguous influence on our world we simply fear. Even now armed with the knowledge that no notion we imagine can appear to us in totality (Sartre, 2010) ghost stories still frighten us, because it is the aspect of communication we reserve for the few things we do not even pretend to understand. That this analogy works so well in terms of what we all hear about AI today should sound more alarm bells than it seems to. The fact that these ‘ghosts’ reside in machines really ought to make the holistic naiveté of our popular figuration of technology obvious to us even on recent cultural terms. Ghost In The Shell (Oshii, 2017) obvious. Still, we continue to develop impressions of consciousnesses and allow ourselves to consider consciousness itself on the basis of a sort of cognitive dualist revivalism. On these terms, describing outdated figurations of consciousness by coining this idea of “the ghost in the machine” Concept Of Mind (Ryle, 2009) deftly dispelled the usefulness of discussing consciousness on cognitive dualist terms. That this was done so long ago should be taken as a harsh warning on how far backwards our understanding of the way we think has gone in the face of the acceleration of our technological development. These ghost stories about AI we keep colloquially telling ourselves are a more immediate threat to us than any eventual singularity.

A lot of big ideas have been included in this paper, all pretty briefly. I do not deny that this would hurt the objectivity of my discussion, if my strategy had been to present a dogma that is to be taken verbatim. The point is that we are sorely lacking discussion of technology considering all of these frameworks. It has therefore been necessary to play tourist a little, in the hope that this text provokes a more pragmatic analysis of our technology, and how it shapes our thinking.

Reflecting on having handed over the painting process to a simple Style Transfer based pipeline has dictated the direction of my theoretical research. Initially, I had apprehensions about starting this process. I was afraid that abstracting some of the corporeal agency away from my creative process would mean I think less through my practice. But The opposite has been the case. Engaging with this medium steeped in superstition has afforded me to reconsider how I think, not just creatively speaking, but holistically. The ideas that I found as a result of the questions given to me by perceiving this process have inspired me to call for a change. Let’s put pride, competition, power, even virtuosity to the side in our creative pursuits for the time being. Let’s see what we can learn by letting our tools effect us gently, before ghost stories become indistinguishable from our reality, not because technology moves so fast, but because our fears make us slow.

It is definitely very easy to imagine AI as a spontaneously emergent evil overlord, simultaneously omnipotent and corporeal. (It is no leap of the imagination to apply this frightening rhetoric to almost any emerging technology). But this does not mean that is the greatest danger something like AI poses to us. The more Immediate threat, to my mind, is that our ghost stories about shallow AI, our messy conflations of power and innovation, and our desperation to exhibit ‘genius’ visions immediately with our whole ‘world’ all only afford us to forget how to think.

Bibliography

Jacq, A. (2019). Neural Transfer Using PyTorch — PyTorch Tutorials 1.1.0 documentation. [online] Pytorch.org. Available at: https://pytorch.org/tutorials/advanced/neural_style_tutorial.html [Accessed 15 May 2019].

McLuhan, M., Agel, J. and Fiore, Q. (2008). The medium is the massage. London [etc.]: Penguin.

Serpentine Galleries. (2019). Pierre Huyghe: UUmwelt. [online] Available at: https://www.serpentinegalleries.org/exhibitions-events/pierre-huyghe-uumwelt [Accessed 13 May 2019].

Atken, M. (2019). Learning to See. [online] Memo Akten. Available at: http://www.memo.tv/portfolio/learning-to-see/ [Accessed 15 May 2019].

Merleau-Ponty, M. and Landers, D. (2013). Phenomenology of Perception.

Suchman, L. (2009). Human-machine reconfigurations. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge. a selected interviews and other writings 1972-77. New York: Pantheon Books.

GABRIEL, M. (2017). WHY THE WORLD DOES NOT EXIST. POLITY Press.

Thompson, N. (2018). Culture as weapon. Reprint ed. Melville House Publishing.

Sartre, J. (2010). The imaginary. London: Routledge.

Ghost In The Shell, 2017. [DVD] Mamoru Oshii, Japan: Manga Entertainment.

Ryle, G. (2009). The concept of mind. New York: Routledge.