Our Communal Story

What have you done recently that you wouldn’t have been able to do if we were not experiencing the impacts of lockdown?

produced by: Eleanor Edwards

Introduction

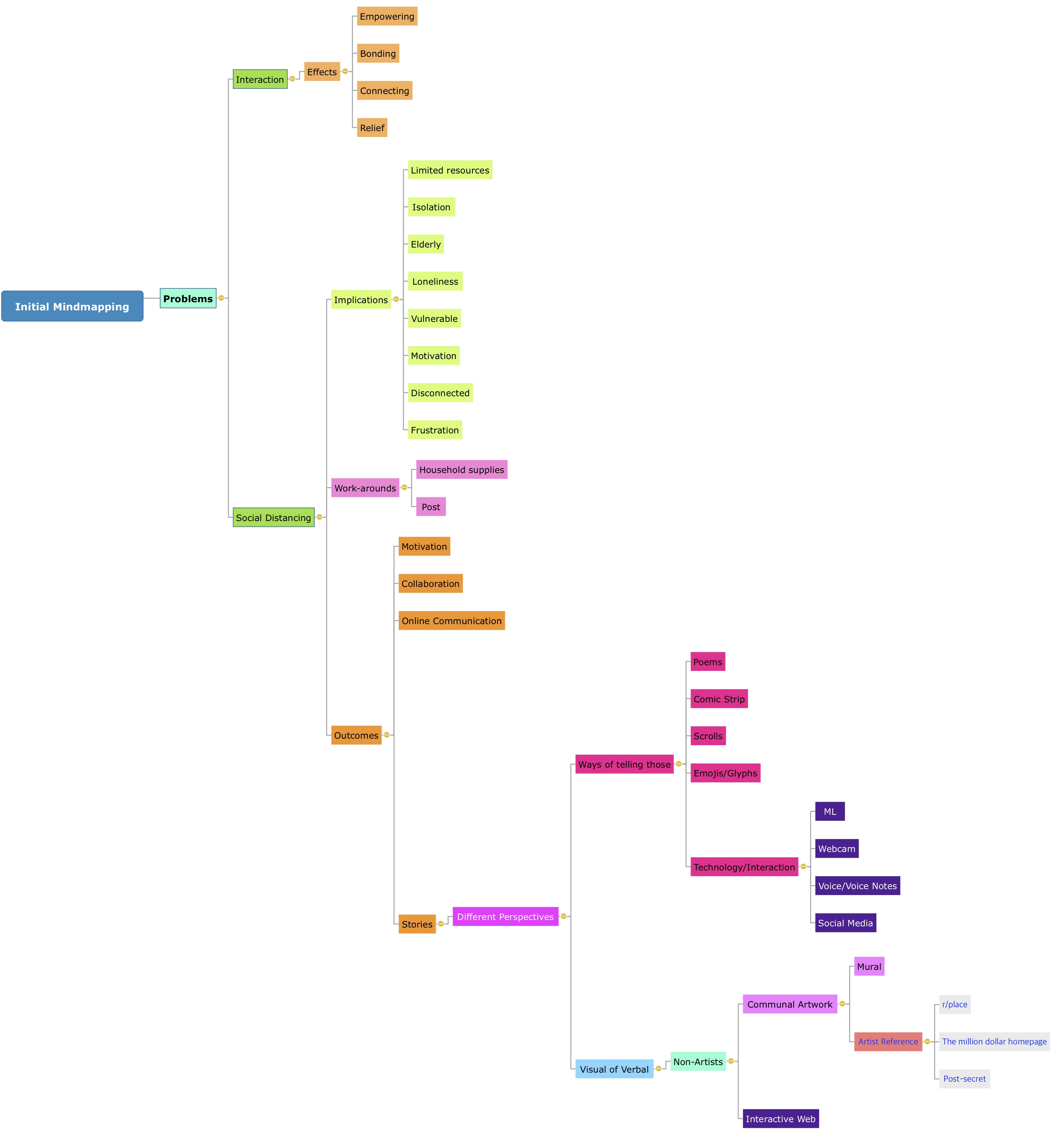

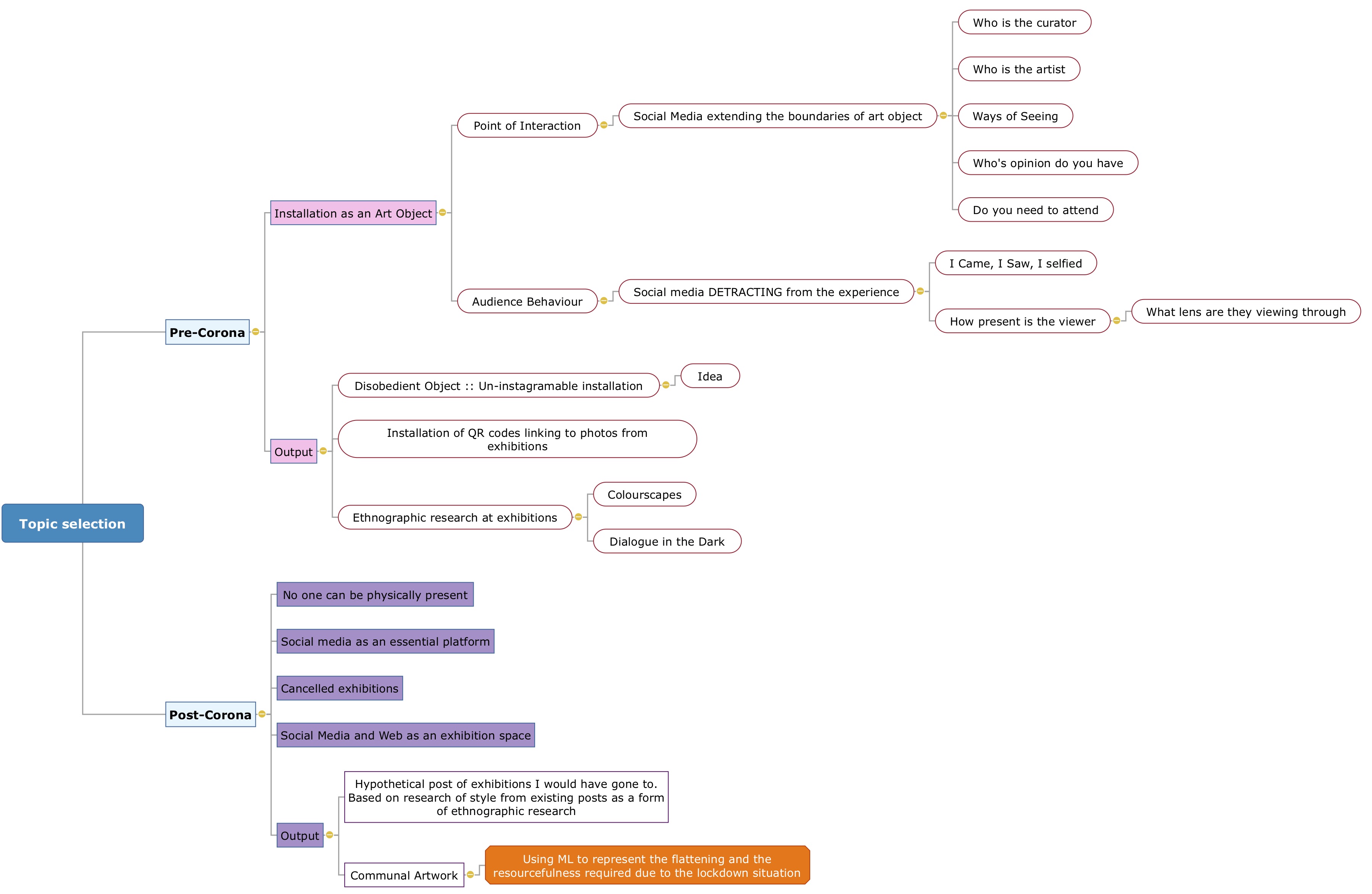

Using a Digital Ethnographic methodology, Our Communal Story (Edwards, E., 2020b), researches, collects and collates individual responses to the 2020 COVID-19 Lockdown. Ethnography is a branch of Anthropology and defined as research through observation “to understand how people live their lives” (Anderson, K., 2009). In this instance, the Ethnographic material was used directly as material for a practice-based research response.

To align itself with the research methodology used, this written documentation will outline some key observations made within the process. These observations cover; social media in relation to art and the art experience, the art object, specifically as interactive and experiential and the physical and digital exhibition space. Reference to commons, a social practice of collective management for collective benefit, and the bounds of the art object are also made.

The practical response, Our Communal Story, is reviewed in its experimental stage and developments are speculated on as a culmination of the contextual observations, whilst also noting its specific position in relation to the COVID-19 crisis.

It is important to note that the lockdown as a response to the global crisis impacted the initial intentions for the research project, although the Ethnographic methodology remained.

Observation A: Social Media and the Art Experience

It is difficult not to examine social media when considering the ‘experience’ as one is used almost intrinsically to document and share the other (Luke, 2019). When deliberating art, the art experience and social media, the engagement, participation and presence of the viewer are considered. Put simply, a viewer experiences art in the physical space, documents this experience, and therefore frames it in their eye, shares this documentation on a social media platform where, another viewer experiences the Poster’s curated, digital version of the physical work in a digital space. That digital viewer enjoys their viewing experience, they might “like” it, but does their art experience belong to the physical or the digital art object and who is the artist of the corresponding work? Through reproducing the art object online, within social media constructs, the message and work are recontextualised as a result of the expansion in the bounds of the art object. Furthermore, authorship in some part is then owed to the social media user as their portrayal of the physical artwork takes a form in the digital space.

It is a trait of social media to diminish claims of intellectual property through the culture of rapid reproduction. Mass production happens side-by-side with mass consumption (Troemel, 2013). John Berger in 1972 in Ways of Seeing, influenced by Walter Benjamin, states that reproductions allow for new meanings, new locations and new narratives that differ from the initial position of the original art object (Berger et al., 2008).

The influx of social media on the art object is re-materialising (Harrison, D., 2013) the art object from finished exhibition piece into a material of the next evolutionary step as a digital art object. This statement frames social media in a negative context, which is reflective of the initial position in which this research stood. This is considered a commonly held position, with social media often cited as having a negative impact on development, mental well-being, communication to name a few aspects (Brooks, 2015).

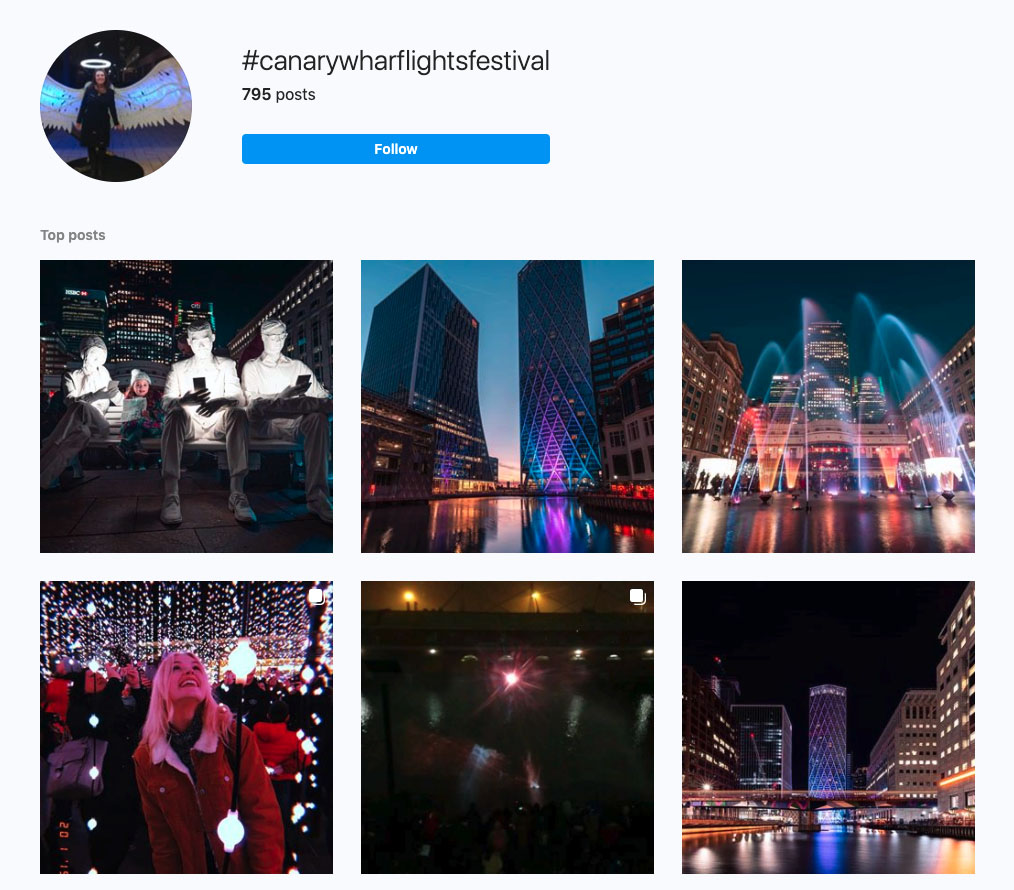

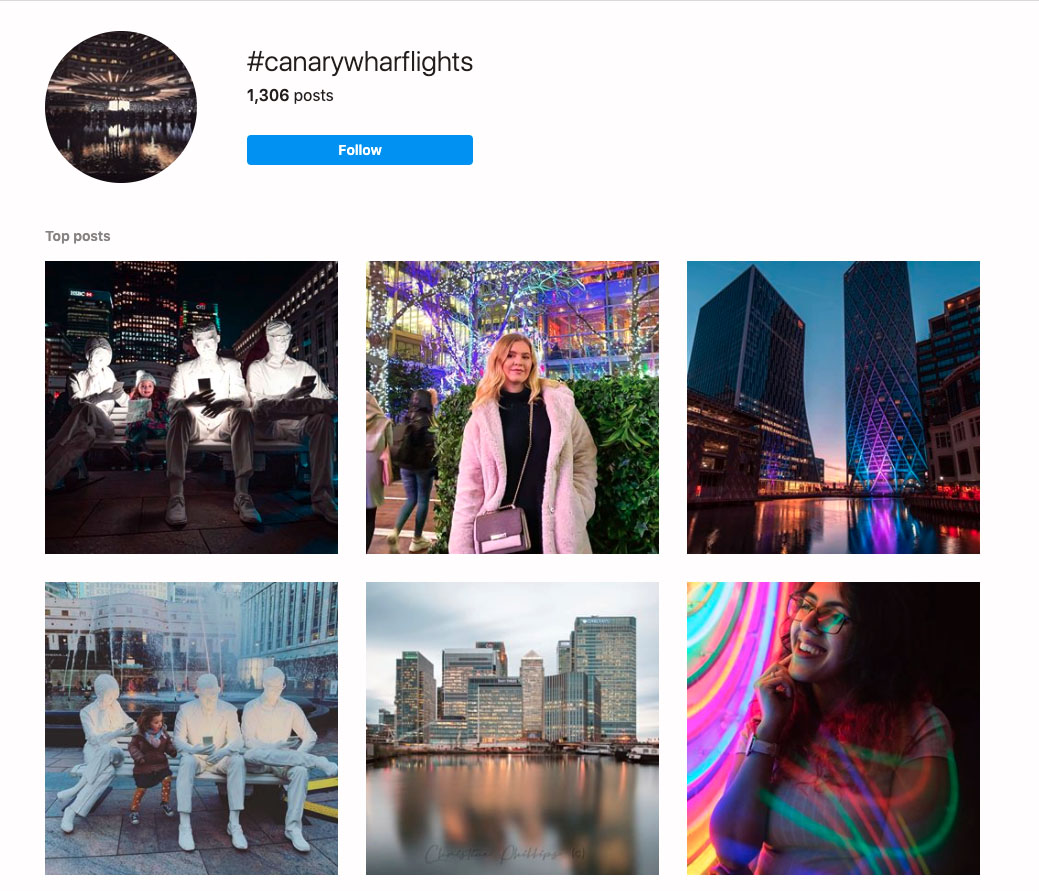

Observation B: The Art Object in the Physical Space versus Digital Space

The physical gallery space is an unequal environment for both artist and viewer. It generally misrepresents the importance of the viewer in the circle of the art object, with barriers and restrictions. These institutions make efforts to portray that which is inside their walls as art, conversely to that which is outside being “everyday” (Troemel, 2013). Although, Experiential and Interactive works shift the bounds of the artwork, so the viewer is included within the process. The environment for a valued experience is often not provided, for example due to volume of visitors. This was personally observed at the Canary Wharf Light Festival, London, 2020, where in some cases the installations were inaccessible due to crowds. In others, the queues unmanageably long as a result of a single person input at the point of interaction with the work and in others still, the view obscured by vast numbers of mobile phone cameras as visitors focused primarily on their own curation of the experience. The sheer volume of photographic reproductions of the Light Festival, in the form of personal experience, available on Instagram has since been observed.

The possibilities for curation and extension of the physical art object within digital dimensions through multiplication and extension of its bounds, that is to say, through reproduction, shift power from the institutions to the viewer as they take ownership and control over their personal experience. The native qualities and behaviours of social media and sharing however, strip this power back again as the users, through their free promotion, reinforce the institution as the premiere sight for exhibition and experience.

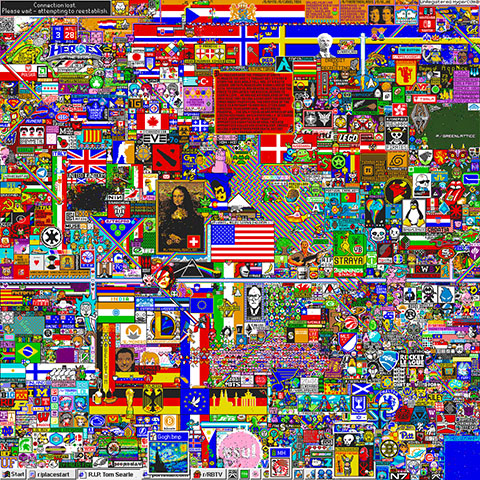

r/Place, Reddit, 2017, was a social experiment hosted on the Reddit platform as part of their annual April Fools’ Day celebration. It culminated in a collaborative art piece produced over 72 hours by Reddit users. In researching this experiment, it becomes clear that through a central digital location a community and further sub-communities were formed. The 1000 pixel square canvas could be altered pixel by pixel in a choice of 16 colours but each user may only lay a new pixel every 5 minutes. “This limitation de-emphasized the importance of the individual and necessitated the collaboration of many users in order to achieve complex creations.” (Simpson et al., 2017). This experiential work has common authorship and as well as social experiment can be considered a communal artwork. The definition of method by the Reddit developers instigated not only the need for communication between contributors but also defined the status of the contributors as equal. The timer that controlled an individual’s ability to add a new input to the canvas and the canvas itself were the only things with elevated status. The traditional format of the Reddit forum was the point where users gathered to form sub-communities, with intentions of creating specific visual material. Bias in status towards bigger sub-communities did occur, however on the whole these sub-communities existed harmoniously. r/Place is evidence that in digital dimensions there are still platforms for Art With Artists, and that not all digital spaces have become sites for “Art Without Artists”, or even “Artist Without Art” (Troemel, 2013).

Observation C: Physical Separated; Digitally Connected

Initially, Ethnographic research for this project was going to be carried out at two experiential exhibitions. Dialogue in the Dark, Hackney, March 2020 and Colourscape @ Wembley Park, April 2020. Comparisons between attendees’ behaviour were going to be made through observation and lightly directed conversation both in the physical space of these exhibitions as well as the digital dimensions that accompanied them. However due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, not only were the March and April exhibitions postponed until further notice, but the world entered into lockdown. It is this lockdown that brought about a positive public mindset on social media (Khan, C., 2020) as it and the digital dimension as a whole became the dominant space for many to socialise and act out their daily lives.

These exhibitions were not the only events forced to reformat. A large number of art exhibitions, music events and design talks flooded to online platforms with motives to not be beaten by the lockdown, moral boosting efforts and aids to connectivity (Daly, R., 2020).

Practice-based Research: Our Communal Story

I opened my practical response with the following thoughts:

· If the digital dimension can be used as a collective and connective space in a time where physical connectivity was forbidden, what was going to be in that space?

· It was clear that during this unprecedented time, many needed comfort and support, both for physical and mental wellbeing, and it was clear many were isolated.

· It was also clear that no matter who you were, this was affecting You.

· In some ways we are all equal in this, we certainly are all going to have a story. In what way can we share those stories with each other?

Drawing on the positive bonds evidenced in the r/Place experiment and the continued growth of the work’s influence (Rytz, n.d.), I set out to define a collective space for the individual stories of lockdown. There were a few challenges to overcome, some specific to the confinement situation, others relating to communal efforts.

· Remoteness: although the catalyst, focus and unable to be completely resolved needed to be worked around.

· Participation: Open to all. Or anyone who wants to.

· Access: Equal to all. In proposing a collective space, in the form of artist practice, what medium can be equally accessed by all?

· Rigidity versus Flexibility: Almost like writing a recipe, there was a need for a framework to be developed to guide and structure the participants. However, the balance between a rigid framework and a flexible one was a constantly shifting form.

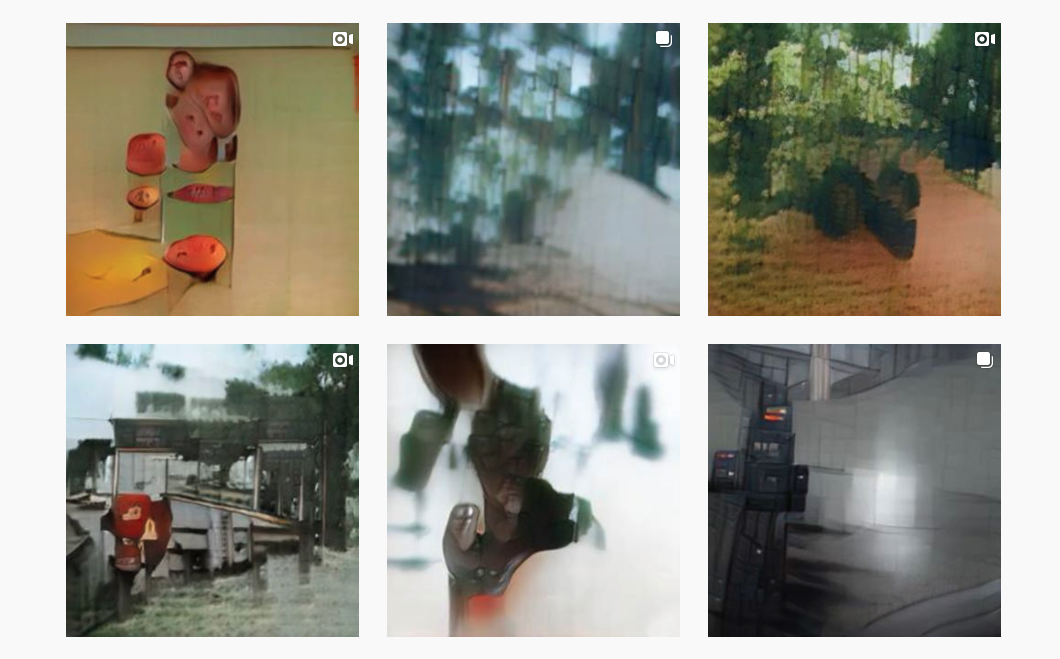

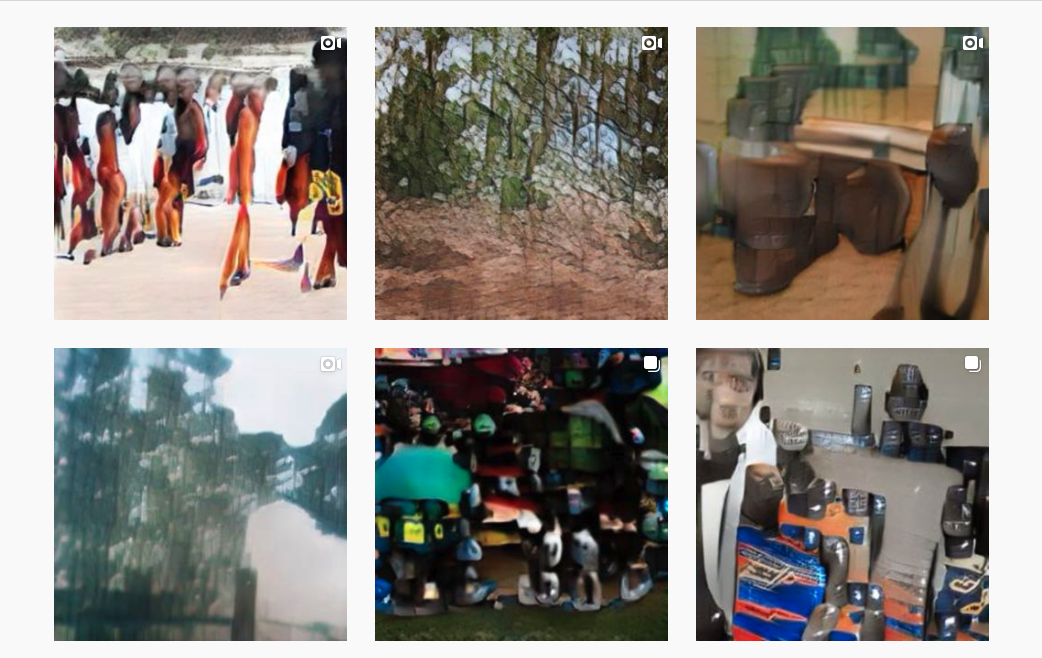

Conscious of the fact that I was proposing a communal artwork with participants that may not consider themselves artists, it felt appropriate to source a medium that would work as almost a silent creative partner. This guided the decision to use a Machine Learning model and this had the added benefit of equalising all partners in terms of creative ability and enabling the participants’ focus to be on their personal lockdown experience. Runway was my chosen tool for accessing ML models.

The site of this collective space was already defined to be within the digital dimension, the physical separation required made that inherent. However, not all participation should have to be digital. As although social media was being championed as the communication tool to promote good mental wellbeing and decrease the physical separation, not all potential participants would be accessors to social media or other digital forms of communication*. I did not want that to be an exclusionary factor for the story collection. With this in mind, I wanted to define a method that would allow for analogue input. The most practical way to do this was to allow the method to develop in a way that would allow spoken data to be used. This resulted in the Runway (“RunwayML | Machine learning for creators.,” n.d.) model, AttnGAN (Xu et al., 2018) being chosen as it works on text-to-image production.*It is noted that the collective space being digital does result in exclusion on that side.

Formatting the gateway for the responses was a significant challenge. A platform needed to be created that would open up the conversation on individual experience. It was actually through conscious observation of my own experience of lockdown that guided my solution. I acknowledged that the mundane act of hanging my washing up outside on a Tuesday afternoon had, even in times of confusion, stress and uncertainty, brought me happiness. This household task would not have been possible on a sunny Tuesday had it not have been for lockdown. To me, embracing this created a positive talisman I could wear. It was also something I was then eager to know about others. What were they experiencing due to lockdown that they would otherwise have not?

What have you done recently that you wouldn’t have been able to do if we were not experiencing the impacts of lockdown?

Reaching out to potential participants, through IM, group chats, phone calls and email, delivered a wealth of information. Through observation of our interactions, I was able to revise the framework of the response collection regularly. In the early stages much concern was given to “how much should I write”. I was anxious not to dictate a specific format of response too much as I really wanted to be as removed as possible. However, to enable AttnGAN to produce visual output, responses needed to be more than a few words. For those concerned about writing too much or over the value of their response, I only reassured them that anything they felt comfortable to say would be totally acceptable; it was their story. Ultimately, I dictated a rough guide between a few sentences and a few paragraphs (Edwards, 2020a).

A multitude of themes can be drawn from the different aspects of this research, in the worded stories: exercise, creative crafts and the outdoors prevail, whilst family and online communication feature strongly as well. This can be expected as the restrictions in place limited activities. However, the reflection towards and the significance placed importance on these aspects differed from response to response, and it is there where the true insight comes.

Although the visual imagery is abstract, viewed in comparison themes occur here too, mainly in the form of colour palettes and form and composition. It should be noted that further experimentation needs to occur with the input of the story into the model, so that the model may respond better to key terms processed individually and collected at the end to complete the story. However, this will involve some curation on my part over participants’ stories, unbalancing the equality of commons, therefore this key term “collation”, if pursued, should be implemented at the response collection stage, ensuring authorship remains with the participant (artist).

Further to the discursive and visual themes the feedback from the participants to myself often resulted in acknowledgement of the positive impact on themselves the process of answering the question had had. This was something I had experienced myself but had made conscious effort not to share with others prior to them participating, to avoid my voice being intermingled with theirs.

“A useful reflective exercise and opportunity to extract some meaning from the experience”

“I really appreciated your request to stop and ponder on what we DO have and CAN do, independently from the situation we are in.”

This appreciation is a mark of success of Ethnography. People don’t say “loading zones are inefficient” they say, “there’s not enough parking”, but through observation research, discoveries into cause of the problem can be made clear, in the case of the parking problem, the inflexibility of defined parking zones and illegibility signage (Isaacs, E., 2020).

A common response to a complaint about a mental struggle is to “just stay positive”. Carrying that out however is another thing, that, more often than not, is just not possible. Therefore, by asking participants to put into words their individual positive takeaways during lockdown, the link between their thoughts and the potential benefits of lockdown becomes more tangible.

The ethnographic methodology used here is not with a direct intention of using the information gathered to influence a direct solution, namely to the lockdown. It is actually the practice of participation in the research format that reflects the gathered information back on to the participant in an effort to highlight a personal solution. The result of the Ethnography is more a form of documentation of a common journey and a provision of space for contemplation within the shared stories of others. If immersed within the themes raised and stories painted, a sense of the collective consciousness can really take hold. Most of the submissions came from participants not only physically isolated, but isolated from other responses. There was no guidance or influence that drew so many to respond talking of themes that it is revealed are common to many. It cannot be denied that activities are likely to be limited in variety due to the decreased opportunities the lockdown allows, but the primary feeling of frustration due to the limitation can be combatted through refocus the mindset towards the constraints. Participants will be aware that they are one of many within this situation but the physical distance from others can weigh down on the ability to find strength and see light. Developing a digital social space for participants and potential participants to congregate reduces the disconnectedness even for a short time.

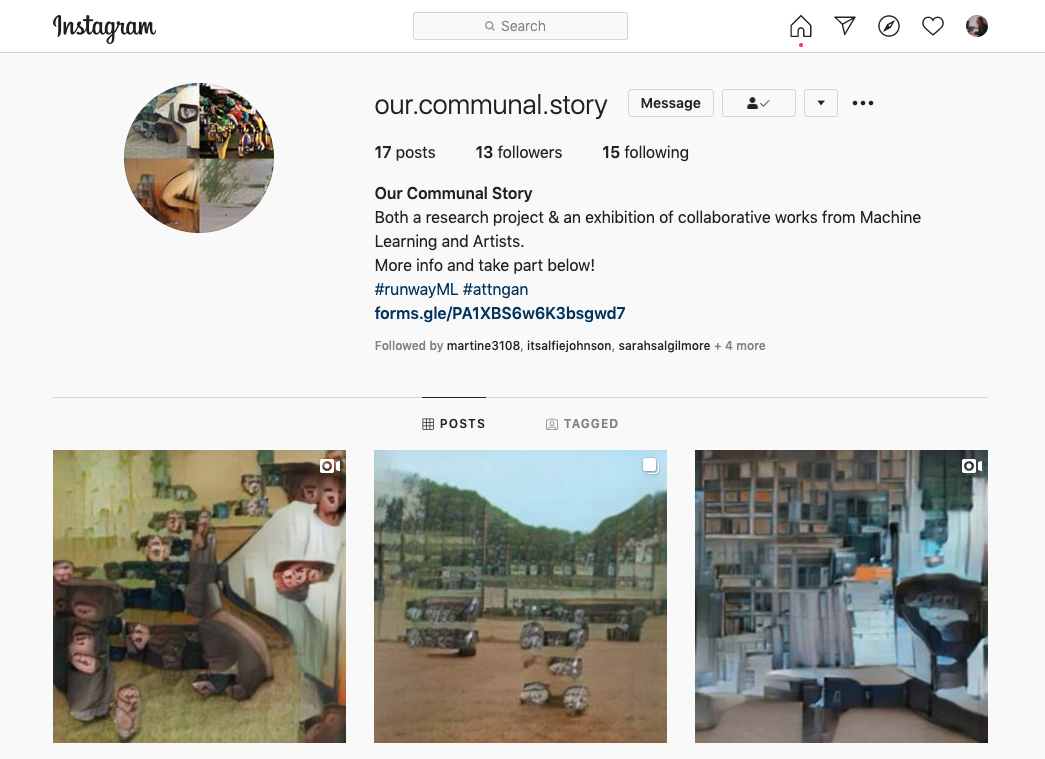

At this stage the artefact exists in experiments on Instagram but this is not the final exhibition space of Our Communal Story. It is not a social media piece, although it grew out of observations of social media engagement. Currently this platform is used as a collaborative exhibition of the current artists participating in the artwork. Ultimately, after developments within the process, both response collection and artistic, Our Communal Story will be an interactive digitally based, multi-located, explore-in-your-own-time documentation of individual stories, arranged and collected both visually and audibly by common themes in a 3D scrabble type way.

Our inability to be physically present in such unprecedented times has encouraged a resurgence of digital engagement that, if carried out correctly, can inspire truly common spaces for shared and valued experience.

References

Anderson, K., 2009. Ethnographic Research: A Key to Strategy. Harvard Business Review.

Berger, J., Blomberg, S., Fox, C., Dibb, M. and Hollis, R., 2008. Ways Of Seeing. London: British Broadcasting Corporation.

Blackmore, S., 2008. Memes and “temes,” TED2008.

Brooks, S., 2015. Does personal social media usage affect efficiency and well-being? Computers in Human Behavior 46, 26–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.053

Daly, R., 2020. The show must go online: inside the rise of virtual gigs during the coronavirus crisis. NME Music News, Reviews, Videos, Galleries, Tickets and Blogs | NME.COM. URL https://www.nme.com/features/the-show-must-go-online-the-rise-of-virtual-gigs-in-the-coronavirus-crisis-2627800 (accessed 3.26.20).

Edwards, E., 2020a. Lockdown 2020 Communal Art Research [WWW Document]. URL https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdaoCCJpbOBqkRpLw6xnC8koug1iX1ExZz70E_GsIPF-84ZdA/viewform?usp=embed_facebook (accessed 5.4.20).

Edwards, E., 2020b. Our Communal Story (@our.communal.story) Instagram profile • 17 photos and videos [WWW Document]. URL https://www.instagram.com/our.communal.story/ (accessed 5.4.20).

Harrison, D., 2013"From the Virtual to the Material: The re-Appearance of the Art Object," International Conference on Cyberworlds, Yokohama, 2013, pp. 226-231.

Luke, B., 2019. Art in the age of Instagram and the power of going viral [WWW Document]. The Art Newspaper. URL http://www.theartnewspaper.com/feature/art-in-the-age-of-instagram-and-the-power-of-going-viral (accessed 3.12.20).

RunwayML | Machine learning for creators. [WWW Document], n.d. . RunwayML. URL https://runwayml.com (accessed 5.4.20).

Rytz, R., n.d. The /r/place Atlas [WWW Document]. The /r/place Atlas. URL https://draemm.li/various/place-atlas/about.html (accessed 5.4.20).

Simpson, B., Lee, M., Ellis, D., 2017. How We Built r/Place. Upvoted. URL https://redditblog.com/2017/04/13/how-we-built-rplace/ (accessed 3.28.20).

Sokolowsky, J., 2016. Art in the Instagram age: How social media is shaping art and how you experience it | The Seattle Times [WWW Document]. The Seattle Times. URL https://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/visual-arts/art-in-the-instagram-age-how-social-media-is-shaping-art-and-how-you-experience-it/ (accessed 3.13.20).

Troemel, B., 2013. Art After Social Media. Art Papers Magazine 37, 10–15.

Xu, T., Zhang, P., Huang, Q., Zhang, H., Gan, Z., Huang, X., He, X., 2018. AttnGAN: Fine-Grained Text to Image Generation with Attentional Generative Adversarial Networks, in: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. Presented at the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), IEEE, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, pp. 1316–1324. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2018.00143