Symbiogenesis in Emergent Art

An Interrelational Study of Space, Technology and Human Interaction

Annie Tådne

Preface

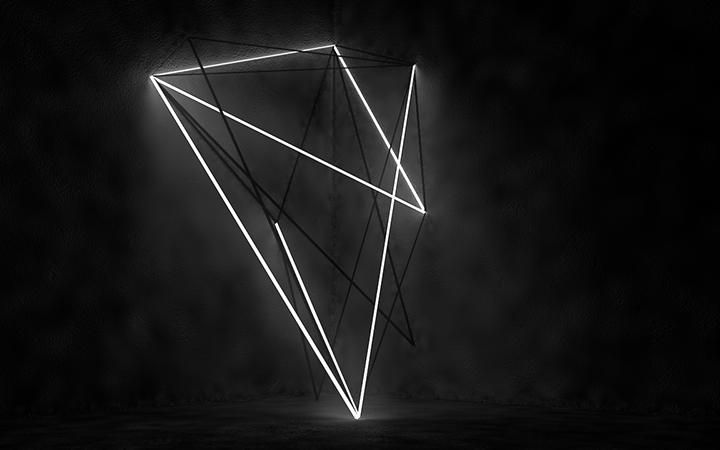

This paper serves as a pre-study for a forthcoming interactive art installation. The gained understanding of how the interrelationship functions within the discussed art-form will form the artistic outcome. This study also shows how complex the system can be, or has to be, to be considered a true emergent art installation. With the cybernetic principles and the aspect of symbiogenesis in mind, there is aspiration for attempting to create a successful artwork following these rules. The fundamental idea is a site-specific installation that has a modular framework and adapts to the inhabited space. Glowing wires are highlighting the place for the exhibition [figure 1]. The wires come to life by reacting to surrounding noises and likewise, output enhanced versions of the environmental sounds. The aim is to make the participant adapt to the perception of stimuli, where she will try to alter the output and become conscious about her movements and the responding effect it has on the digital output. Thus, an interchange will take place between the space, the human movements and the digital output.

The Harmony of Art and Technology

When thinking about the connection of elements in an interactive art installation that utilises a technological audiovisual medium, associations can be made with early sciences. Harmonics is the scientific name given to musical tuning, although the word can be examined in a broader context where musical tones are the reflection of the balance and the order of the cosmos, the algebra of divine forms, mediated through our senses [1]. The more profound understanding of harmony was observed in the works of Pythagoras and Plato, where abstract principles of whole numbers and their ratios become reachable to our senses through music. When speaking of harmonics, they addressed the relationships between tones. This relationship was something that interested architects and artists, where a building or a sculpture is a representation of a larger dynamic, such as the harmony of the cosmos, whereas the parts combined create a harmonious whole [1]. The rules of harmonics in music and its mathematical principles can be transferred to visual consonance. Alberti argued [2] that the same numbers used in musical calculations of harmonics can be translated into our visual senses and 'fill the eyes and mind with wondrous delight' [2, p. 305]. Technology has given artists valuable capabilities of manipulating light, visuals and sound according to the principles of harmony, and the relational properties are remarkable to acknowledge when studying and practising site-specific art.

Technology is bound to the human world in other ways than just functioning as instruments and tools [3]. Instruments help us peer into new worlds, they feedback information we can exploit, they connect the real world with the artistic and virtual world, they help us compose what we call beauty or meaningfulness, that further can exalt our senses, emotions and intellectual capacities [4]. Disciplines such as art and science have the purpose of studying aspects of our universe, and function as explorations of the inner and outer domains of humanity. If these disciplines serve to extend the borders of knowledge by building roads into alien places, art is created [4]. The aim of this study is to expand the boundaries of knowledge of artistic practice, which may generate paths to uncharted territories in future artworks, and hopefully inspire fellow artists to take similar paths. For artists interested in intelligent technological systems, it is intriguing to study the myriad of relationships, and its dynamics, that emerge in interactive art installations. Furthermore, it is essential to emphasise what impact the surrounding environment has on participation and perception in the dynamic that arises. This study serves to research the interrelationship between space, technology and human interaction in art projects. By elucidating these questions, successful artworks using this particular art-form may be more likely to arise.

Processes of Interaction of Art

To understand interactive art installations, the perception of art has to be discussed. There has been a shift from art being considered as an object, to art being considered as a process [5, 6, 7]. When technical developments open up virtual worlds, today, the shift is moving towards a dual nature involving processes in both physical and virtual spaces [8].

The day before yesterday, Marcel Duchamp placed a urinal in a gallery and declared it art. Yesterday, we wondered if the object in the gallery was real or simulated. Today, we place in our gallery not an object but a process. Tomorrow, we will wonder if the process is real or simulated [4, p. 10].

Since the change of perception of art is going from static objects, towards processes and later processes with dual-nature, a distinction between the artworks that simply respond and systems that are capable of changing and evolving has to be made. Paine [6] is searching for a definition of what interactivity means when being applied to digital systems. He states that to develop a truly engaging and interesting artwork, we must seek to establish systems and experiences that are not predefined. The interactive art-form should reflect on the individual’s nuance of input in a unique way. Paine argues [6] that the term interactivity is wildly abused, and there is a significant difference in an interactive versus a responsive system. If the installation system is not developed in such as it changes in response to accumulated user input, it should instead be considered a responsive installation. A responsive system is built on event triggers, and do not take into consideration the information that streams in-between the individual triggered events. An interactive installation is built on ongoing qualitative data, and processes changes in the behaviour of the continuous stream of data [6].

Interactive art installations are probable to evolution-like features, where each element responds cumulatively, and form an interrelationship where each quality is unique and necessary for the process to survive. Cybernetic research [9, 10, 11] provide support for this logic, where the total is greater than the sum of the parts, and their relationships and responses to each other define the characteristics to the entire system.

Embodied Cognition as Perception of Space

Before examining cybernetic and post-human thoughts, the effect of space in an interactive art installation has to be examined. De Certeau [12] differentiates the term place from space, where place is an immediate and stable configuration of positions; ‘the order (of whatever kind) in accord with which elements are distributed in relationships of coexistence’ [12, p. 117]. Space conversely is a practised place ‘composed of intersections of mobile elements’ [12, p. 117], in the sense that we can realise a place through our own spatial practice (e.g. physical movement or listening). To illustrate the difference, we can think of a park in a city, where the structure of paths, benches and trees are static elements and a representation of the place. The space, on the other hand, the movements in this place, it is a place for meetings, conversation, relaxation, it is a place where birds are singing, and children are playing. Although it is not determent what kind of movements that occur, at other times there might be a protest, a wedding ceremony or a concert happening; space is of dynamic nature and something that affects our life experiences. Fells [13] analyses soundscape compositions in relation to space, and points out elements that ‘invite others to partake in our own spatial experience, in the way the sounds of a particular location interact with our imagination, perception and memory’ [13, p. 290]. When attempting to understand the impact of spatial attributes in works of interactive art, an examination of how we generate meaning in space is to follow.

For generating meaning in space Merleau-Ponty notices the body, ‘I am conscious of my body via the world . . . I am conscious of the world through the medium of my body’ [14, p. 82]. The body is not simply a container or instrument of agency, but functions using ‘stable organs and pre-established circuits’ [14, p. 87] below the threshold of conscious intention. Embodied cognition is present at all levels of thought and expression [15]. If all abstract thinking is metaphoric, then creativity and imagination become crucial factors in considering embodied cognition. Aesthetics become instrumental in our understanding of how we generate meaning in our realms. When awareness of how a perception of space is constructed and in what way meaning is generated through spatial and embodied cognition, it is possible to use space as a deliberate choice of artistic expression.

Space as Expression

Macedo [16] asks the question ‘What is space in music?’ [16, p. 247] and suggests a typology of five categories for the use of spatial terms and expressions in music: metaphor, acoustic space, sound spatialisation, reference and location. Within the framework Macedo suggests, useful for this study is the concept of space as location, where the meaning of space, afore-mentioned by De Certeau [12], is produced by the physical presence of the spectator in a particular place. It can be conceptualised as spatial perception and is associated with site-specificity. Gibson [17] defines spatial perception as a perception where all the perceptual systems are involved in identifying the environment: the orienting system, the haptic system, the taste-smell system, the auditory system and the visual system. Sound is part of the perception of space, as the characteristics of sound produce specific expectations related to it.

Collis asserts [18] that when time-based principles are subordinated to spatial principles, where a sound work is situated in a physical space, it enables arbitrary sound material to be used by the composer. A piece that prioritises space over time is, ironically given its title, Cage’s composition 4’33’’ [18]. It can be read as a composition made for its environment, as the music is made by the performance site itself. Space, performers and audience are together seen as a totality, where the listener is a part of the space, immersed in it and also subject to it. This approach materialises arbitrary sound to be present within a composition. ‘Noise lends itself to site-specific sound art’ [18, p. 383]. Macedo [16] also mentions the work of John Cage as experimenting and breaking norms of space, where he defies sounds relative to the ones the audience is expecting to perceive in a specific location. The composition Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano, by its name, propose a piece for a grand piano in a concert hall, but instead, the audience is presented with percussive and gamelan-like effects.

Live soundscape music is incorporating the element of chance by including natural sounds of the environment. Murray Schafer is using natural settings in his compositions [16, 19], and by doing so, space is adding to the reception of the performance. The intention of using space as location in music is to bring the background of the aural perceptions to the foreground and allow the audience to listen to the environmental noises like music. ‘This characteristic of producing a reflection about the role of sound in the constitution of a global perception of space and about the interaction between different perceptual modalities in the production of spatial perception is what characterises . . . works in which space as location is a central and structural concern’ [16, p. 247]. Truax [19] states the amplified opportunities contemporary technology has when it comes to utilising space as an element in music, but also mentions the importance of being thoughtful about what is prominent to say about the social, cultural and environmental contexts the spatial element gives. Thus, an artist or composer has to elucidate the intention of incorporating arbitrary sounds or background elements in their work, since the noise itself can implicate a lot of meaning.

Incorporation of background perceptions applies to our visual senses as well, as demonstrated when Collis studies [18] how space and body exist in the works of Ryoji Ikeda. The spatial relation affects our bodily response [18], and the installation is the space, rather than the Heideggerian view of artwork as revealing space. When noises in space, that conventionally are filtered away from foreground elements, instead are emphasised and used as an artistic expression, the whole dynamic and the factors that affect the state of the artwork have to be acknowledged. A deeper understanding of how individual elements such as space and human interaction in art installations function in a dynamic synergy is followed by frameworks for systems theory.

Cybernetics and Posthumanist Thoughts

Castellanos formulates a framework [20] for interactive art through the linked theories of cybernetics, phenomenology and posthumanist thoughts. The art-form facilitates and amplify a construction of a reality that is active, dynamic, collaborative and co-evolutionary in our highly technologized society.

Interactive art or, as Castellanos calls it, emergent art, can enable a bodily, felt sense of the co-emergent dynamic system, and therefore bring greater consciousness to the co-evolutionary nature of our relationship with technological environments. Symbiogenesis is used as a term for a better understanding of the experiences that give rise to ‘a sense that we are co-emergent, that is, that we exist in mutually influential relationships with our increasingly technological environment’ [20, p. 160]. Proposed here is that interactive art can give rise to a heightened, transformative sense of co-evolution because the intelligent technological system develops a level of agency, autonomy and novel forms of animism. Like Paine [6] suggested a distinction between interactive and responsive art, Castellanos explains the distinction further by thinking of emergent art-forms as what they do rather than what they are. It is the evolving sets of emergent relations of agency and alterity, or here called co-evolutionary, that give rise to symbiogenesis in interactive art. The symbiogenic experience is establishing relevance through the theoretical lens of Merleau-Ponty’s existentialist phenomenology to intelligent systems, neo-cybernetic theory and the material practices of cybernetics.

Cybernetics present us with an ontology of unknowability where humans and their environment exist in a constant co-emergent interplay, where the world is viewed as a place that we constantly adapt to through embodied action and performance of agency. This domain establishes a connection to Merleau-Ponty’s concept of ambiguity, which refers to anything that is undergoing development or is continuously open to determination. Emerging arts experiences have dynamic and flexible, rather than fixed, essences, which creates this connection between the two frameworks.

Viewed through a lens of neo-cybernetic theory, what classifies emergent art practice is its indeterminate complexity. Capra [5] clarifies that instead of considering the dynamics of a complex system to be understood from the properties of its individual parts, the part is merely a pattern in an inseparable web of relationships. The features of the individual elements are only understood by the dynamics of the whole. The interactive art-form thematises reciprocal interplay of human and non-human systems [20]. It depends on our presence and how we respond, instead of what we see or hear, or rather, the shifting relations between these. A concept of closure and boundary is defined by adaptively selecting aspects of the environment to which the system will respond, where it establishes its own viability, or autonomy, as a system. A system’s boundary and closure are specifically what allows the system to become entwined with its environment.

An emergent artwork resembles cybernetic models of conversational interactions between system and environment, where agents stand out in their alterity and function as triggers. In doing so, a larger sense of embeddedness and complexity of other systems in a higher order fashion emerge: ‘in a sense a co-evolution of body, world and technology, a feeling that we are not separable from our technologies but like the environment, are continuous with them’ [20, p. 165]. An equivalent of this feeling is the feeling of immersiveness, essential for creations within virtual reality and immersive arts. The process is defined by its open system, where the organisation is maintained through continuous exchange of energy and matter with its environment [5].

To be co-emergent with an ‘other’, such as with the environment, amplifies a sense of heterogeneity and is a core element of the emergent arts. This is referred to as collectively emergent autonomy [20], when observing a set of environmental patterns while simultaneously being part of them, thus influencing the very dynamics that one is observing. The observer of an artwork is also a participant that influences the artwork, therefore an endless, constantly evolving, loop is created.

The natural roots of intentionality are the organism’s orientation towards what is significant and valent in its environment. This significance is not pre-existent but instead enacted and brought forth by the system via circular relations [20]. Intentionality arises out of the systems boundaries, and the totality of relationships that define the system as an integrated whole [5]. This pattern of self-organisation is called autopoiesis and has extensively been studied by Maturana and Varela [21]. The organisms in emergent art installations decide how to act by their closure and are in their constant movements capable of maintaining an intriguing setting.

Conclusion

Human-technology co-evolution already exists, and the emergent arts may make us more aware of its implications. There is a complex interrelationship between space, technology and human interaction in art projects. Our process-based perception of art has a hybrid space with a co-existence of real and virtual. Art is no longer regarded static and bound to objects. Consequently, interactive art is to be distinguished from responsive systems. Space is a practised place, which is critical to notice whereas meaning is to be generated through our body in space. Noises derived from space can be used as an expression, where background elements are instead situated in the foreground, which makes the awareness of space in interactive art projects is essential. A true interactive art-form is considered emergent when it is in co-evolution with its elements and thus studied to be in symbiogenesis. The relationship between ambiguity and cybernetics is to be found when the artwork is in constant development and simultaneously in continuous interplay. By exchanging energy and matter with low-level systems is why organisms of the installation can feel continuous with its environment. A core element of interactive arts is the experiences of observing an environment while simultaneously being part of it, thus influencing what one is observing.

In the field of practice-based research, this study has identified key elements within interactive art and possibly created opportunities for progress in arts-practice. A more abundant knowledge of the interrelationship between space, technology and human interaction in art projects, can lead to greater success in future artworks. Proposal for prospective examiners is to support the arguments with quantitative research. The study identifies the complexity of emergent and symbiogenic art, consequently, this study may lead to meaningful awareness for artists when making creative decisions. Insofar, new roads to unfamiliar places can be created.

References

[1] B. Alves, “Consonance and Dissonance in Visual Music,” Organised Sound, pp. 114-119, 2012.

[2] L. B. Alberti, J. Rywert, N. Leach and R. Tavernor, On the Art of Building in Ten Books, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999.

[3] N. Prior, "Putting glitch in the field: Bourdieu, Actor Network Theory and Contemporary Music," Cultural Sociology, vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 301-219, 2008.

[4] M. Novak, "The Music of Architecture: Computation and Composition," Sonic Arts: Music and Architecture, 2007.

[5] F. Capra, "Systems Theory and The New Paradigm," in Systems, London, Whitechapel Gallery Ventures Limited, 2015, pp. 22-27.

[6] G. Paine, "Interactivity, Where to from Here?," Organised Sound, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 295-304, 2002.

[7] G. Paine, "Interactive, Responsive Sound Environments A Broader Artistic Context," in Engineering Nature: Art and Consciousness in the Post-Biological Era, Bristol, Intellect Books, 2006, pp. 137-143.

[8] V. Korakidou and D. Charitos, "The spatial context of the aesthetic experience in interactive art: An intersubjective relationship," Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research, vol. 9, no. 2-3, pp. 277-283, 2011.

[9] N. Weiner, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, Paris: M.I.T. Press, 1961.

[10] R. Ascott, Engineering Nature: Art and Consciousness in the Post-Biological Era, Bristol: Intellect Books, 2006.

[11] P. Lichty, "The Cybernetics of Performance and New Media Art," Leonardo, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 351-354, 2000.

[12] M. d. Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. S. Rendall, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

[13] N. Fells, "On Space, Listening and Interaction: Words on the Streets Are These and Still Life," Organised Sound, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 287-294, 2002.

[14] M. Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith, London: Routledge, 1989.

[15] C. Mamakos and P. Stefaneas, "Consciousness reframed: Art and consciousness in the post-biological era," Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 169-176, 2016.

[16] F. Macedo, "Investigating Sound in Space: Five meanings of space in music and sound art," Organised Sound, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 241-284, 2015.

[17] J. J. Gibson, The senses considered as perceptual systems, Waveland: Prospect Heights, 1966.

[18] A. Collis, "Ryoki Ikeda and the Prioritising of Space over Time in Musical Discourse," Organised Sound, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 378-384, 2017.

[19] B. Truax, "Genres and Techniques of Soundscape Composition as Developed at Simon Fraser University," Organised Sound, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 5-14, 2002.

[20] C. Castellanos, "Co-evolution, neo-cybernetic emergence and phenomenologies of ambiguity: Towards a framework for understanding interactive arts experiences," Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative research, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 159-168, 2016.

[21] N. K. Hayles, How we Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics, London: The University of Chicago Press, 1999.

[Figure 1] A. Tådne, 3D simulation of the installation.