Dance Puppets

The ethical implications of technology-mediated manipulation of human subjects for performance/entertainment purposes

Produced by: Clemence Debaig

"Can a body cope with experiences of extreme absence and alien action without becoming overcome by outmoded metaphysical fears and obsessions of individuality and free agency?" (Sterlac 2005 [3])

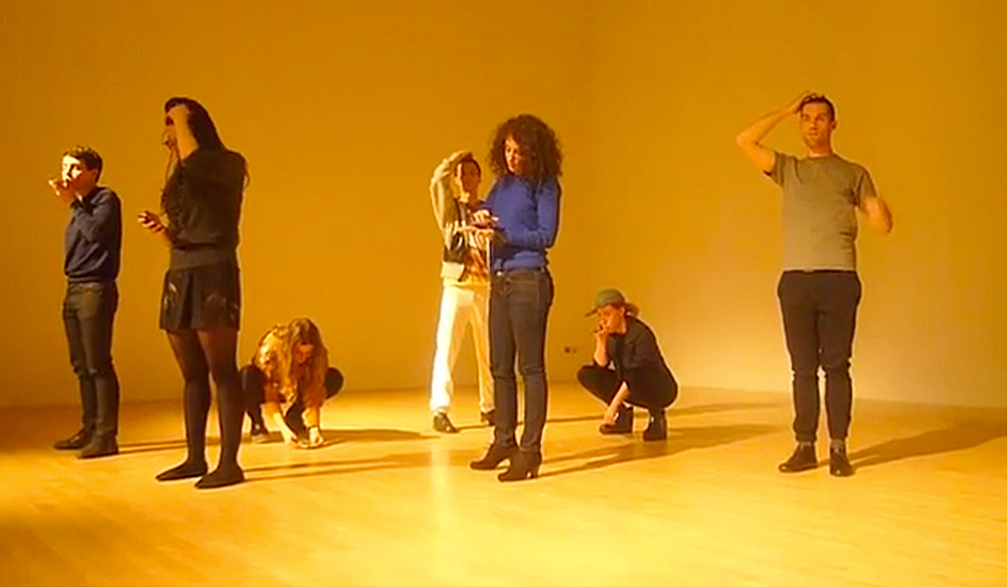

Fig. 1: Experiment 4 with vibrating device

Introduction

Most professional dancers have been trained specifically to be malleable in their movement vocabulary in order to realise the vision of the choreographer. This flexibility sometimes makes it more difficult to explore new material, and the beauty in the diversity of bodies can be missed - our natural gestures, the everyday habits and the uncanny movements.

I have always been fascinated by observing non-trained dancers move and discovering their natural body gesture. Most people tend to say that they are “not dancers”, that “they can’t move” or that “it’s not for them”. But there are a few situations where they feel free to move and express themselves, when no one is watching or when playing games. This project is born from observing people playing with interactive installations or experimenting with VR, encouraging movements that seem choreographed for the outside viewer.

This research project aims at exploring how interactive systems can encourage people to dance without them necessarily noticing it, revealing the beauty in everyone’s natural ways of moving.

A series of 4 experiments has been realised with individual participants and with a group, exploring what type of stimuli can generate what type of movement. But also, researching the potential of the creation of a ballet performed by non-trained dancers, reacting live to a series of stimuli - shifting the role of the choreographer to designing interactions instead of set movements.

In parallel, the project explores the different levels of motivations and agencies between the "conductor" and the participants. But mostly, it questions the underlying ethical issues that may arise with the technology-mediated manipulation of human subjects for performance/entertainment purposes

Existing works

To understand better what type of experiments had already been done in the past and how this research project would bring new elements to the discussion, I have been looking into existing works from several artists (full collection of projects available here). A few projects are worth mentioning here as they are exploring some aspects of the questions I started with.

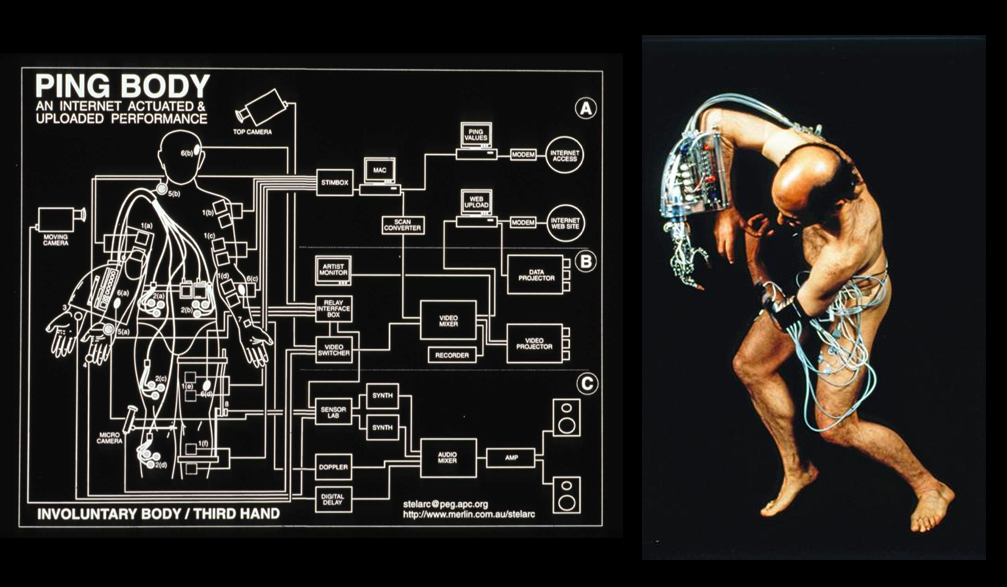

Fig. 2, 3 & 4: The Opticons, Compagnie DCA - ZYX, Jodi - Ping Body, Sterlac

The Opticons by Compagnie DCA is a series of interactive installations, based on optical illusions and theatre tricks, with the purpose to make people dance. Using photographic and digital technologies, they invite visitors to be playful with their own image, especially when their body is in movement. This is directly related to the practical side of this project and considering that Compagnie DCA is a dance company, it is a really interesting source of inspiration to create new experiments based on similar principles.

ZYX by Jodi also invites participants to interact with a system, but this time it happens on their phone, guiding users through a series of gestures with simple instructions, from turning in a circle to raising one's arm up and down. Where The Opticons were inviting people to play and explore, ZYX asks the participants to be precise and provides feedback when the movement has been realised correctly. What is interesting is what happens when several users are interacting at the same time and the position of the external viewers watching this strange dance taking place. It starts questioning the agency of the participants and the intention of the artist who had designed those interactions to make them “perform” for the entertainment of the bystanders.

Going further in the notion of control, I would like to mention two artists. First of all, Sterlac with Ping Body and Re-wired / Re-mixed where he invites the audience to control, via an online interface, the prosthetic arm he is wearing. Sterlac has also demoed a device at the Transmediale in 2007, allowing someone to control another person’s muscle activity using electric impulsions, leading to unvoluntary movements.

Secondly, we can look into Epizoo by Marcel.li Antunez Roca, where the muscles on his face are connected to a machine, allowing the audience to control his facial expression.

In the work of both artists, if can find the questions of consent, boundaries, and surrender to the agency of an external participant. This really touches upon this notion of manipulation for performance purposes. But in the work or Sterlac and Roca, they are both putting themselves and their own body in this situation, giving consent to participants to manipulate them.

What I would like to explore in my project is what it implies to involve random participants in the experiment, where they might not be equipped to challenge the situation and the underlying ethical questions.

Our obsession with free will

We can wonder why it’s important to ask this question about control, especially when it involves technology as a proxy.

As human beings, we are obsessed with freedom and whatever could challenge it. Technology is more and more at the centre of those worries. We constantly analyse the politics in place around us, motivated by the fear of losing our autonomy.

This is a notion also introduced by Foucault in the Birth of Biopolitics (1978-1979) [2] when he presents the key principles behind liberalism. He explains that one of those principles is the ability to regulate itself by continuous critical reflection on government practice, motivated by the fear of governing too much and reducing one’s freedom.

This obsession with not being too much governed is all also fueled by the fear of not being able to see the big picture and the real power relations in place. This becomes particularly relevant when technology is employed as a proxy to govern.

Commenting on his work, Sterlac also covers those concerns when he mentions our “metaphysical fears and obsessions with individuality and free agency” (2005). He says that “we fear the involuntary” but yet we are becoming more and more integrated and dependent on technology.

This also echoes Jane Goodall’s words when talking about Sterlac’s work:

"Yet we are conscious automata programmed to be furiously protective of our autonomy. Agency is precious to us, so much that we are haunted by fears of its loss or usurpation. Spirits that possess our minds, alien influences that cause our limbs to move at the will of another, parasites that take over our bodies, surroundings that confuse and overwhelm us: these are the nightmares of Western modernity." (Goodall 2005 [3])

In the context of this research project, would participants develop concerns for their free agency? And if put in front of an audience, as the external witnesses of the situation, would they challenge the agency of the participants?

Protocole of the experiments, using Laban Movement Analysis to create a framework of interactions

As a way to structure the experiments, using the Laban Movement Analysis theories [6 & 7] came as a natural way to build a framework around how the body moves and cut its components into smaller pieces.

The other interesting aspect of the Laban approach is that it was not meant to be used for analysing the movements of dancers but it had been created for describing, visualising, interpreting and documenting human movement in general. And it had been developed by observing humans doing everyday life activities at first. This makes it even more relevant for this research project as the purpose is to involve non-trained dancers.

Based on the existing structure of the Laban Movement Analysis, a new framework has been created in order to identify interesting experiments. The framework is essentially a matrix between the Laban parameters and a set of categories of stimuli (eg Auditive, kinetic, aspirational, etc). The full framework is available here.

After selection, this resulted in 4 experiments:

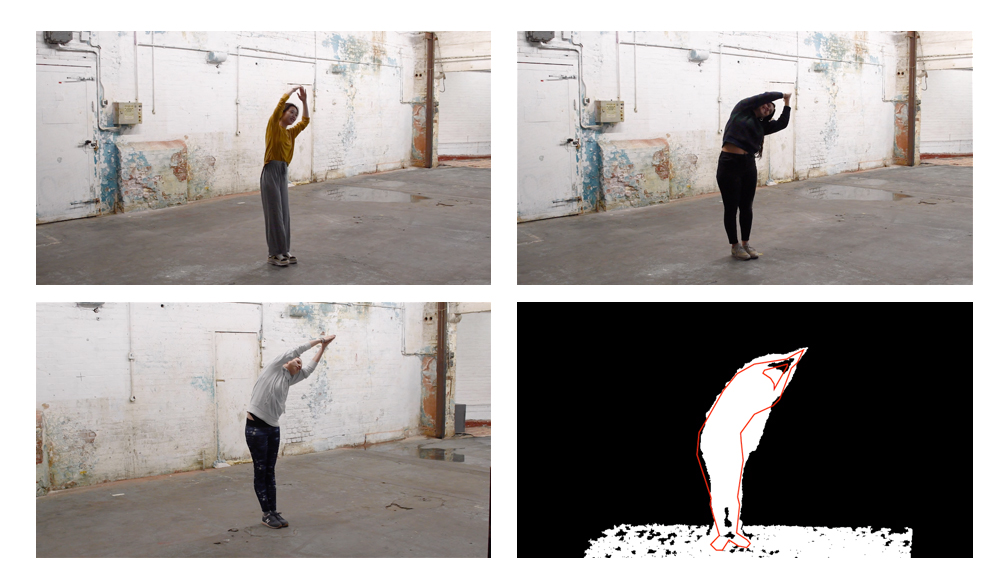

- reproduce a shape (using computer vision with feedback on a screen)

- reach the dots (using computer vision with feedback on a screen)

- follow the point (using a laser pointer on the floor and participants’ bodies)

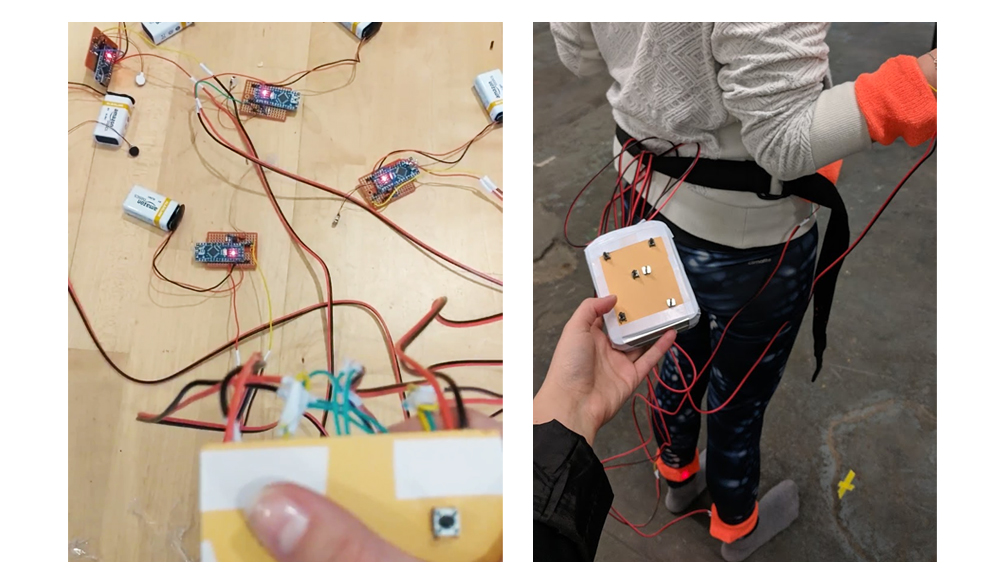

- move a body part when it vibrates (equipping participants with mini vibrators on different body parts)

Those experiments have been realised on 6 participants, with 3 individual sessions and a final group session. The final session was set up as a performance with a very limited audience.

The learnings from those experiments served as a background for theoretical thinking, answering some of the initial concerns but opening the field for new reflections.

Fig. 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9: Experiment 1, “Reproduce a shape” - Experiment 2, “Reach the dot” - Experiment 4, “Vibrating device” - Detailed view of the vibrating device - Experiment 2, “Reach the dot” during the group session

Video 1: Showcase of the 4 experiments

Is using HCI hiding the intention behind the experiment or the performance?

Using technology in this process is introducing a lot of concerns about the role it plays regarding control and how this is influencing or modifying the agency of the participants - especially because interactivity encourages people to transgress personal boundaries and blurs the digital, fictional and physical space.

When analysing how we engage our bodies when interacting with installations, Nathaniel Stern, building on Massumi’s point of view, mentions that “as participants, we are instrumentalised interactions” (2013) [9], and that there can be a tyranny of interactions, forcing particular and predictive movements that are conceptually pre-formed.

This opens a lot of potential for designing those interactions on purpose to create a predefined set of movements and contribute to a sense of performance through choreography. But at the same time, the activity of designing those interactions could hide its true purpose to the participants’ eyes. The way they would react to the system is already pre-designed but they have the illusion of free agency.

This can also be linked to the notion of Magic Circle in game design theory, introduced by Johan Huizinga (1938) [8]. Is technology creating a playground inside the wider performing space, some sort of inner circle inside the circle?

"All play moves and has its being within a play-ground marked off beforehand either materially or ideally, deliberately or as a matter of course. ... All are temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart." (Johan Huizinga 1938 [8])

This questions the perception of the participants and their ability to see the bigger picture. We can wonder if by using HCI and technology, we are somehow tricking the participants in focusing only on the task in front of them, making them forget that there are a conductor, other participants and external viewers and that there is a performance happening involving them. Is it acceptable or is this breaking the unspoken contract between the artist and the participants? Can we still consider this as consent if the big picture is not explicit?

Unspoken contract and informed consent

One element that has been mentioned during the experiments, but also explored in the paper The Ethical Implications of HCI's Turn to the Cultural (2015) [4], is the trust already in place between audience and artists. For example, when going to a gallery, there is an unspoken contract ensuring that the piece will somehow be appropriate for its audience or not put the person at risk.

But this trust could be challenged when the purpose of the exchange changes slightly. If the artist decides to observe how visitors interact with his/her pieces for research purposes. The audience now becomes a subject. Does it change the initial invisible agreement?

We can ask the same question with the experiments realised in the context of this research project, and especially what role technology and interactivity play in this context as it is used as a proxy between the participants and the artist.

We can link this question to Snelting point of view. Technology is so integrated in our lives “it has become our natural habitat. We practice software until we in-corporate its choreography.” (Snelting 2006 [14]), and we have lost the ability to question it.

We can add to this point the fact that participants are not dancers, they can’t challenge what is asked from them physically as long as it’s in the realm of their physical abilities. And if they can’t challenge the software, we can then wonder if they have the ability to challenge the situation and see the bigger picture. And is their consent informed enough?

In this entanglement of agencies and relationships, who is in control?

The participants, the choreographer/designer, the interactive system and the audience, all are agents forming a complex web of relationships. They have different intention, agency, motivations and perception of the situation but all influences each other.

What is the extent of the perception of the intention of each agent? Especially when it comes to the relationship between the artist and the participants, we can wonder how much of the choreographer’s intention is perceived by the participants.

Considering the context of the performance, as participants are reacting to stimuli, do they really have their own agency? Or do they become the instrument of the artist’s vision? And are participants perceiving this alien agency? “It’s questioning simplistic notions of identity and agency and how a body is positioned in a complex and interacting system enmeshed in a high-tech terrain." (Sterlac 2005 [3])

The audience is also influencing those relationships as its presence gives a different intention to the experiment. It is also ”implicated in the ethics of what they view by being there, and their implication affects this act of viewing, creating agency for the viewer." (The Ethical Implications of HCI's Turn to the Cultural [4])

So, in this entanglement of relationships, we can wonder who is in control, who has authority and who is responsible? Is it the artist who has designed the interactions? Is it the technology providing the series of instructions? Is it the participant who is reacting to the stimuli and performing? Is it the audience who transforms it into a performance by its presence?

At the same time, considering the complexity of the entanglement, we can also question if it's relevant to ask who is in control.

"I am reconciled to the fact that in a complex technological terrain where there's multiplicity of feedback loops, it's no longer meaningful to ask who's in control" (Sterlac 2005 [3])

When influence and control generate freedom

During the experiments, participants mentioned that the interactive system freed them up from their self-consciousness and made them move in unexpected ways. And even if they were following instructions, they felt freer to express themselves physically. Those participants being non-dancers, they are not necessarily familiar with the potential of their physicality and the interactive system allowed them to explore a new way of expressing themselves.

This whole project started by expressing a concern about freewill and exploring theoretical grounds to see if the experiment would cross boundaries of consent and control. But the feedback from the participants went in the opposite direction. They expressed no concerns about free will as the potential tradeoff helped them expand their horizons.

As the interactive systems were generating a series of stimuli and participants felt free to react the way they wanted to those stimuli. Even if most people reacted in a similar way, they had the perception of creativity. We can then wonder if the action of the artist is only governing the participants’ freedom and technology is acting here as an enabler?

This echoes Foucault’s words about liberalism (1978-1979 [2]) where he describes the role of government as a way to organise freedom. Maybe the way to see the role of the choreographer/designer in this context is to organise the physical creativity of the participants and reveal the beauty in their unique ways of moving.

Conclusion

This project started with an initial exploration of how interactivity can encourage people to dance without them noticing it and see if it would be possible to create a performance with volunteers reacting to a series of stimuli. This lead to the main concern explored in this report around the ethics of manipulating human beings using the proxy of technology for performance purposes.

Having considered some specific concerns around free will, I have explored how this experiment could challenge the participants freedom. The themes explored suggest that the use of interactivity and HCI could hide the initial artist’s intention

s from the participants, using entertainment to achieve a wider purpose and giving alien agency to the participants.

The fact that participants are non-dancers makes them unable to challenge what is asked from them. And similarly, the place of technology in our lives makes it difficult to challenge its role as it is too integrated in our environment. So, we’ve questioned the notion of consent and the level of information and background required for this consent to be valid.

The entanglement of relationships, agencies and authorship made us question who is in control in this situation. But we’ve also argued that the complexity is what makes the performance and each component is influencing the other. Therefore questioning who is in control is irrelevant.

The experiments have revealed that the perception of the participants was almost the opposite and they were feeling freer to move, completely ignoring any concerns for their own agency. This made me reconsider the power relations in place and redefine the role of the choreographer/artist as the person governing the freedom of the participants, using technology as a proxy to enable their creativity.

I would like to finish this report by broadening the discussion to other potential versions of this experiment. One element that has been highlighted several times by participants is the role of the human behind the interactive system. This is linked to the notion of trust mentioned earlier. Consent is given because they trust the artist behind the experiment. But what would happen if the participants were invited to interact with a stand-alone machine? Maybe including some randomness or artificial intelligence? And what if the system was directly controlled by the audience?

Annotated bibliography

1. Salter, Chris. Entangled - Technology and the Transformation of Performance. The MIT Press, 2010. Print.

In Entangled, Chris Salter explores technology’s influence on artistic performance practices. In Chapter 6: Bodies, he focuses on how bodies are extended and made anew by technology, and the impact on the perception of those bodies in the context of performances. The chapter questions the assumed quality of human flesh as the key element of performance and explores new ways of transforming it into a mutable object and subject. The book appears as a catalogue of previous works and artists sharing similar questioning and field of research, providing a good overview of the status of the reflection in this field of research.

2. Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics. Lectures at the College de France 1978-1979. Seuil/Gallimard, 2004. Print.

In The Birth of Biopolitics, Foucault develops the notion of biopolitics introduced in previous lecture series. He focused on the study of liberal and neo-liberal forms to draw onto the birth of governmental rationality, questioning the role and status of the state. In the context of this research project, it is interesting to draw parallels with Foucault’s theories to analyse the power relations in place and the fear of losing freedom and autonomy.

3. Edited by Smith, Marquard. Sterlac - The Monograph. The MIT Press, 2005. Print.

In Sterlac - The Monograph, Marquard Smith invites a range of writer to comment on Sterlac’s work, followed by an interview of Sterlac himself. It aims at offering a comprehensive study of Stelarc's work practice in over thirty years. Sterlac's work being very close to the concerns brought by this project, this analysis brings a variety of perspectives on the notions of control, technology and body in the context of performance art.

4. Benford, Steve ; Greenhalgh, Chris ; Anderson, Bob ; Jacobs, Rachel ; Golembewski, Mike ; Jirotka, Marina ; Stahl, Bernd Carsten ; Timmermans, Job ; Giannachi, Gabriella ; Adams, Matt ; Farr, Ju Row ; Tandavanitj, Nick ; Jennings, Kirsty. The Ethical Implications of HCI's Turn to the Cultural. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction (TOCHI), 08 September 2015, Vol.22(5), pp.1-37.

In The Ethical Implications of HCI's Turn to the Cultural, the group of authors review the ethics of engaging with HCI, interactive installations and theatrical performances. Based on the analysis of several case studies, they identified interesting ethical challenges, including boundaries, consent and integrity, relevant to this research project. They also propose a framework to manage ethical challenges at the intersection of those existing frames mixing HCI, performances and installations.

References

5. Kozel, Susan. Closer - Performance, Technologies, Phenomenology. The MIT Press, 2007. Print.

6. La Barre, France. On Moving and Being Moved - Nonverbal Behavior in Clinical Practice. Routledge, 2001. Print.

7. Davies, Eden. Beyond Dance: Laban's Legacy of Movement Analysis. Routledge, 2001. Print.

8. Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Angelico Press, 2016. Print.

9. Stern, Nathaniel. Interactive art and embodiment - The implicit body as performance. Gilphy Limited Book, 2013. Print.

10. pp. 32-45 Altered, expanded and distributed embodiment: the three stages of interactive presence

Waterworth, John ; Waterworth, Eva (), Interacting with Presence: HCI and the Sense of Presence in Computer Mediated Environments, De Gruyter Open, 2014. Print.

Miller, Kiri. Playable bodies dance games and intimate media. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. Print.

11. Robert Klanten, Sven Ehmann, Verena Hanschke, Lukas Feireiss. A touch of code: interactive installations and experiences, Berlin: Die Gestalten Verlag, 2011. Print.

12. Streeck, Jürgen. Interaction and the living body. Journal of Pragmatics, 2013.

13. Snelting, Femke. A fish can’t judge the water. 2006. Online. Available from http://www.constantvzw.org/verlag/spip.php?article72#