Mutable VR

Post-human particle systems as a multichannel musical instrument.

produced by: Chris Speed

Introduction

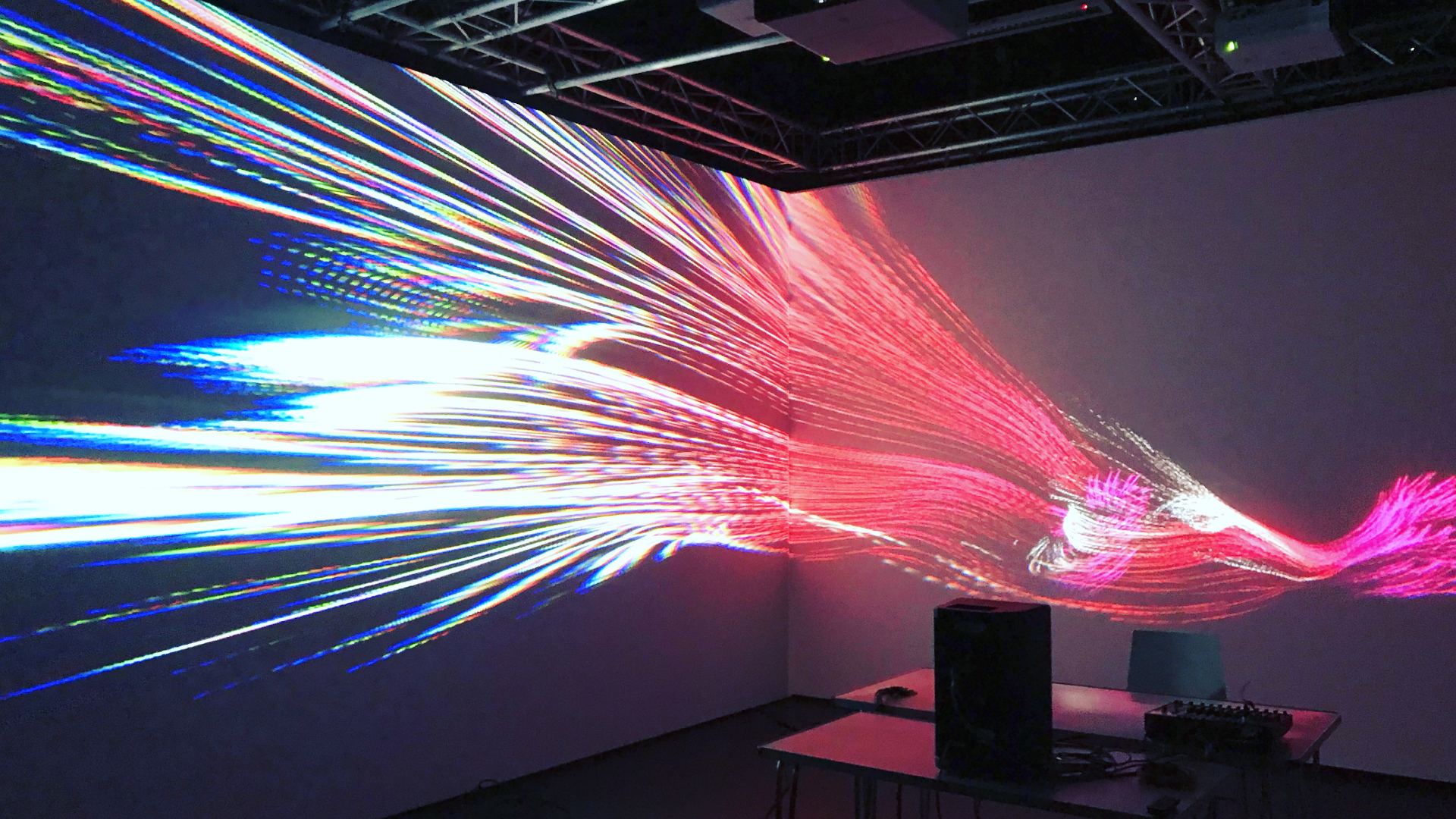

Mutable VR is an immersive installation and live performance in which 360 spatial audio is controlled within virtual reality. Conceptually inspired by wave–particle duality in quantum mechanics and posthuman phenomenology, this project explores an embodied experience of microsound. This piece is a culmination of my recent body of work exploring themes of duality, embodiment and abstraction, the title itself is taken from the programming term “Mutable” (a changeable object). The artwork combines the latest VR technology with custom software to connect real time particle simulations to music and redefine how we perceive our bodies within virtual worlds.

Building upon my evolving artistic practise, this piece takes a post-humanist account of performance due to my loss of sensory affordances to the audience. By the situating the piece within Sonics Immersive Media Labs (SIML), my hope was to incorporate viewers into the artwork and share sensory experience by exploring both inner and outer space simultaneously.

Concept and background research

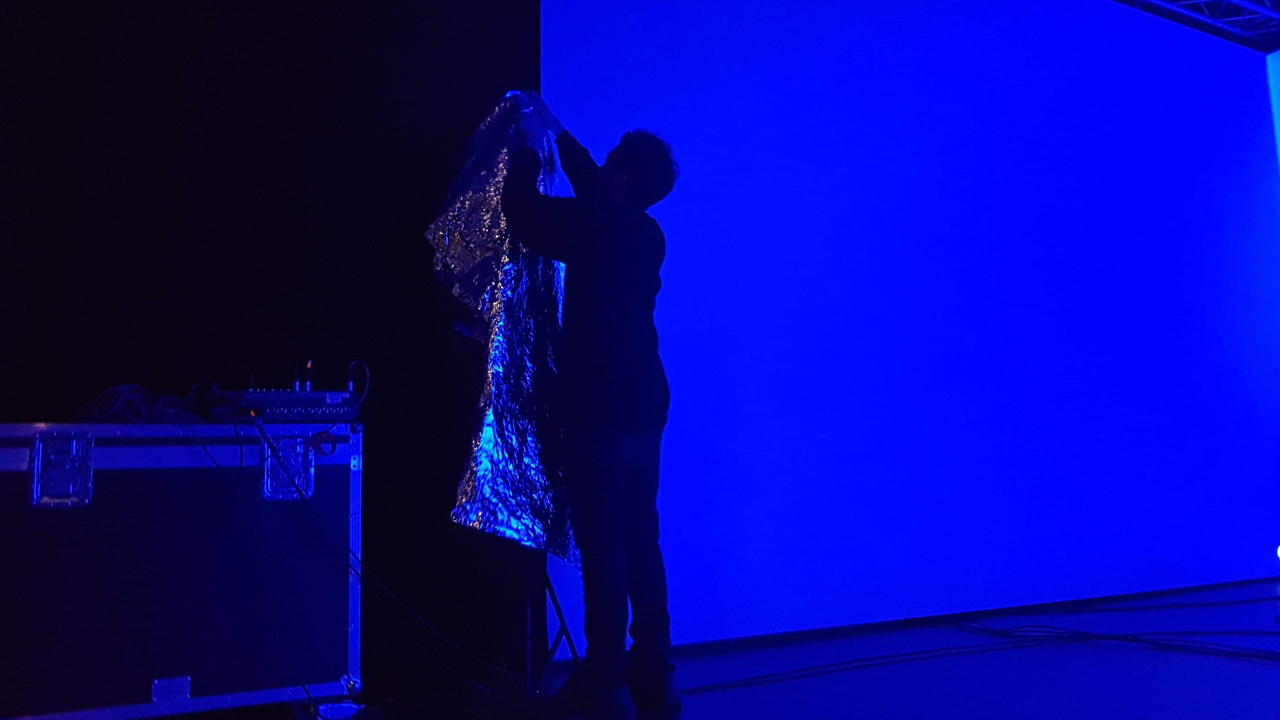

The conceptual underpinning for this work came from my report for the computational art theory module in which I wrote about how ideas within quantum physics could inspire new forms of polymorphic embodiment in virtual worlds. Karen Barad’s metaphysical writing on diffraction was highly influential to the design of my virtual reality application. As the piece progresses, the user’s hands begin to disperse over time and gradually diffract into the environment. Barad’s theory of agential realism allowed me to see particle systems as non-human collaborators. Her post humanist ideas even extend to the notion of wearing a head mounted display, appearing as a cyberbody on stage. Jenna Ng’s concept of Derived embodiment informed my phenomenological understanding of virtual body ownership. Our bodies are vehicles for perception, so abstracting human shaped figures, like a Francis Bacon painting, can lead to powerful reactions. Virtual reality to me is a highly meditative practise in which we can safely experience altered states within the confides of sensorimotor contingencies.

Many other artists influenced this project such as the iconic computational artwork unnamed soundsculpture by onformative. Among the wave of new 3D granular synthesizers, Tadej Droljc’s Singing Sand covers similar ground to my piece. Mark Fell’s Parallelling#2 was a notable inspiration on the hooded figures which exist as diffractive entities. Along with Murray & Sixsmith’s writing, the idea of polymorphic representations is addressed in Future You by Universal Everything. From virtual reality artworks, I wanted to conjure a darker interpretation of Marshmallow Laser Feast’s We Live In A Ocean Of Air and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s Endodrome.

For me the idea of using virtual reality as a performance medium dates back to 2016 when I first saw Ash Koosha’s VR show at the ICA. Since then I was determined to work out how to figure it out for myself. Further musical inspiration for this project came from Actress’s Transmediale show, Ben Frost and MFO’s This Centre Cannot Hold Tour, Death Peak by Clark and the sonic aesthetics of Sunn O))). Daniel M Karlsson’s performance at Norberg Festival this year got me interested in the field of convolution technology. His contribution to the Anrikningsverket journal inspired me to reach out to him for acoustic impulse responses of the iron mining facility / performance venue Mimerlaven. I am profoundly moved by idea of capturing the essence of spaces which have great sentimental importance to me then convolving them together to create new reverberant environments.

Technical

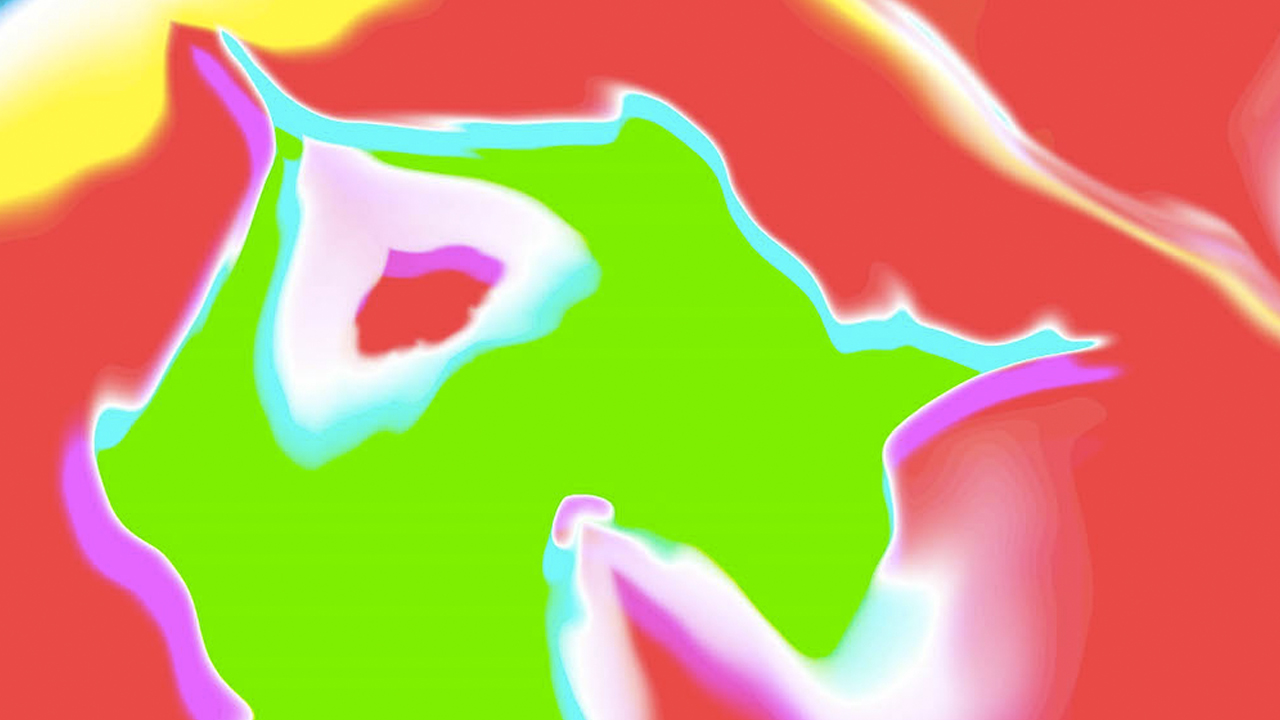

In the beginning I adhered to the agile development approach by rapid prototyping with daily sketches in the Unity game engine. I normally commit to a month of daily coding to explore computational processes and learn what is possible with the tool. However, this time the work was in service of my final project, so I put emphasis on iterating through certain concepts. Particularly I wanted to master shaders as harnessing GPU power would allow me to create increasingly more complicated visuals.

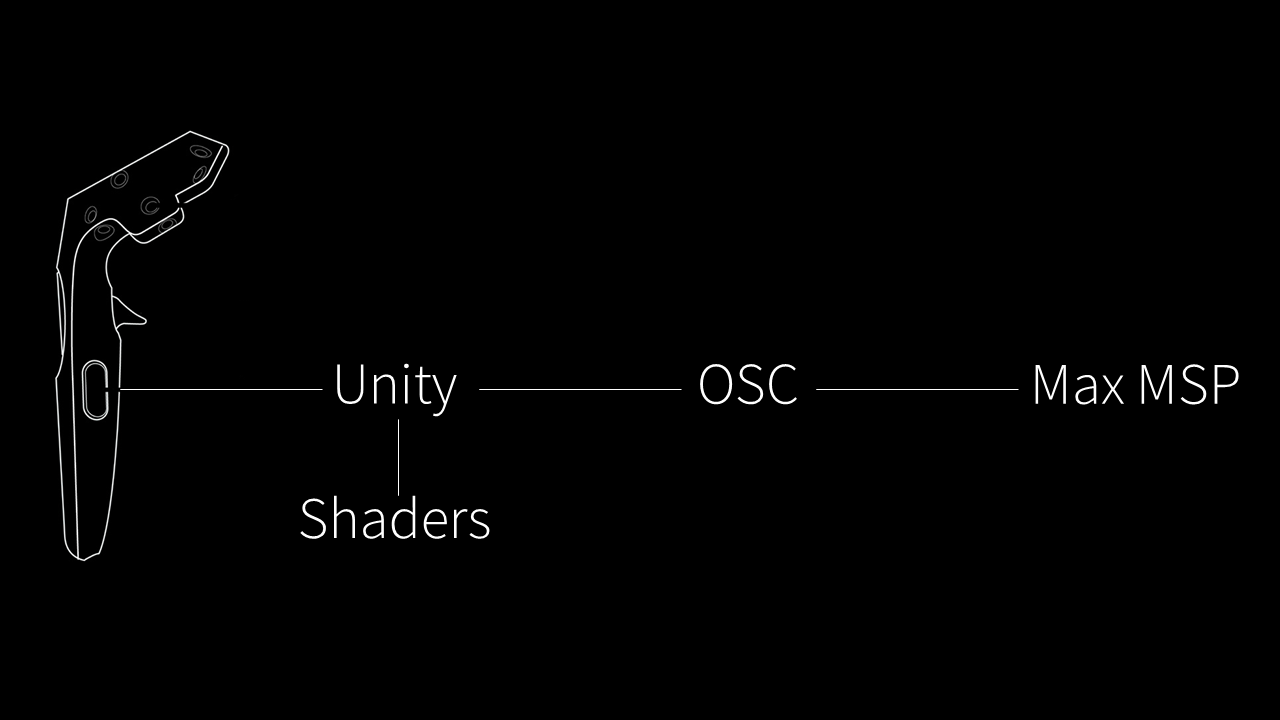

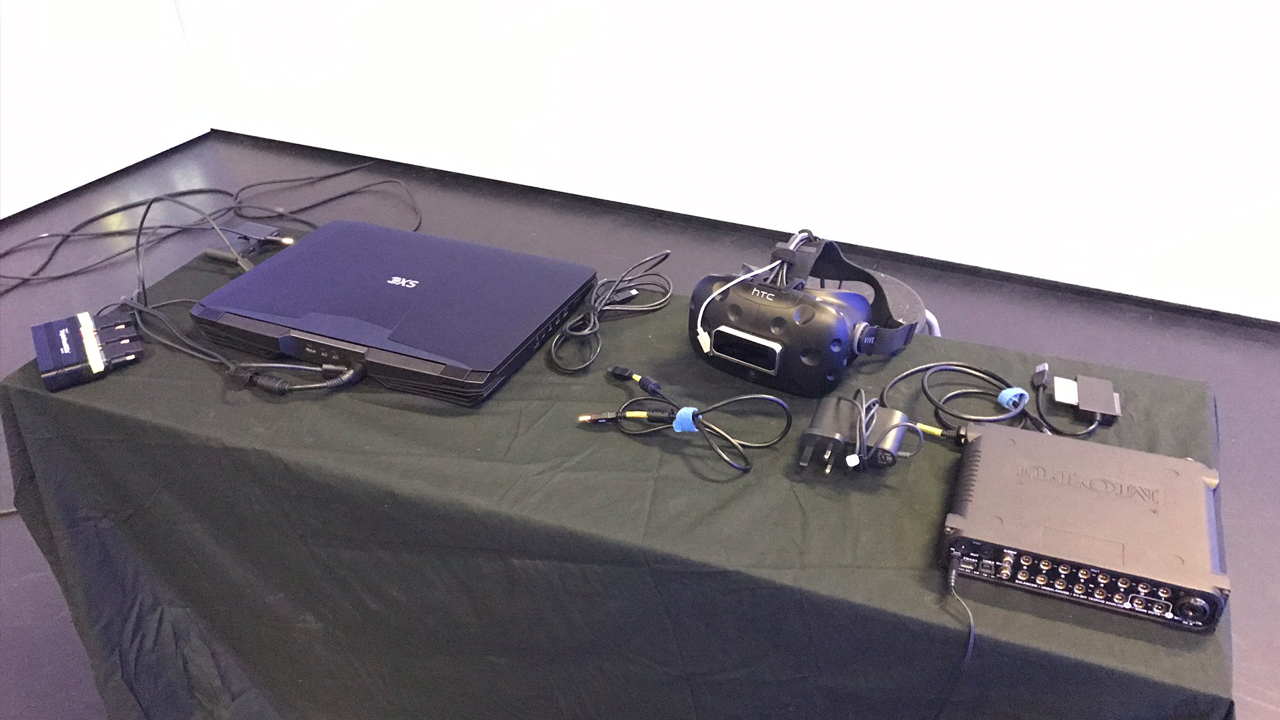

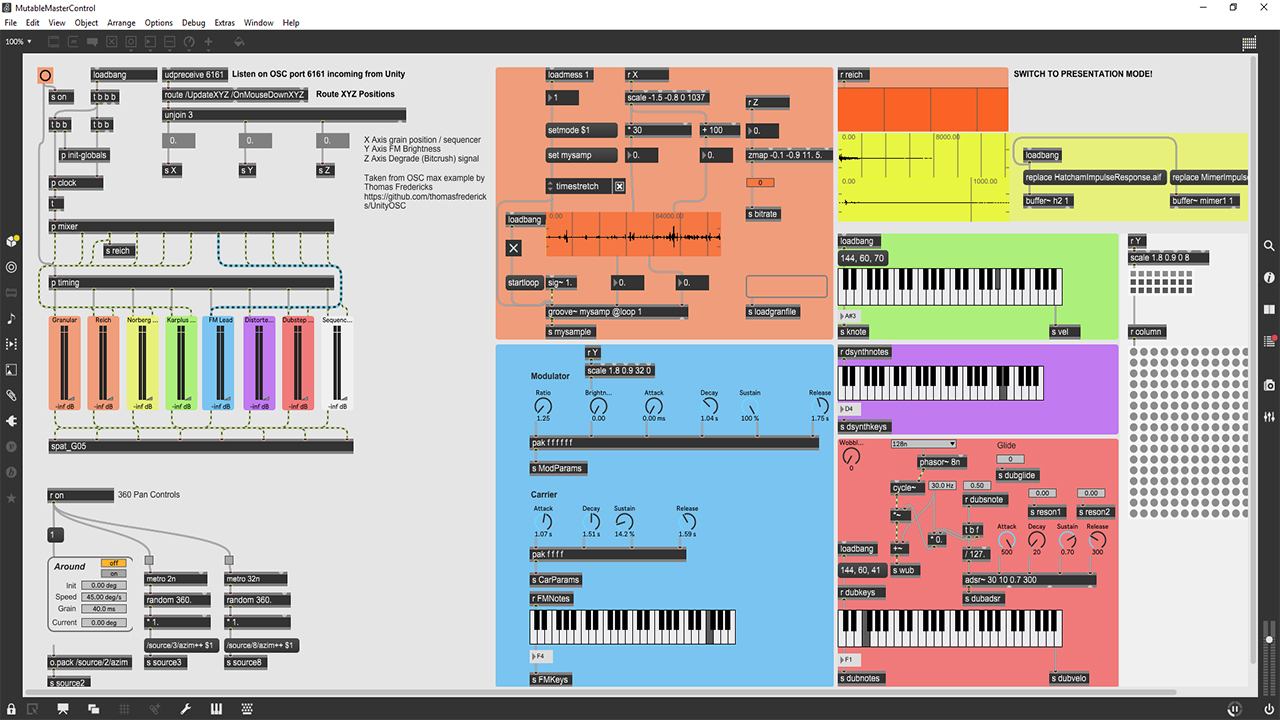

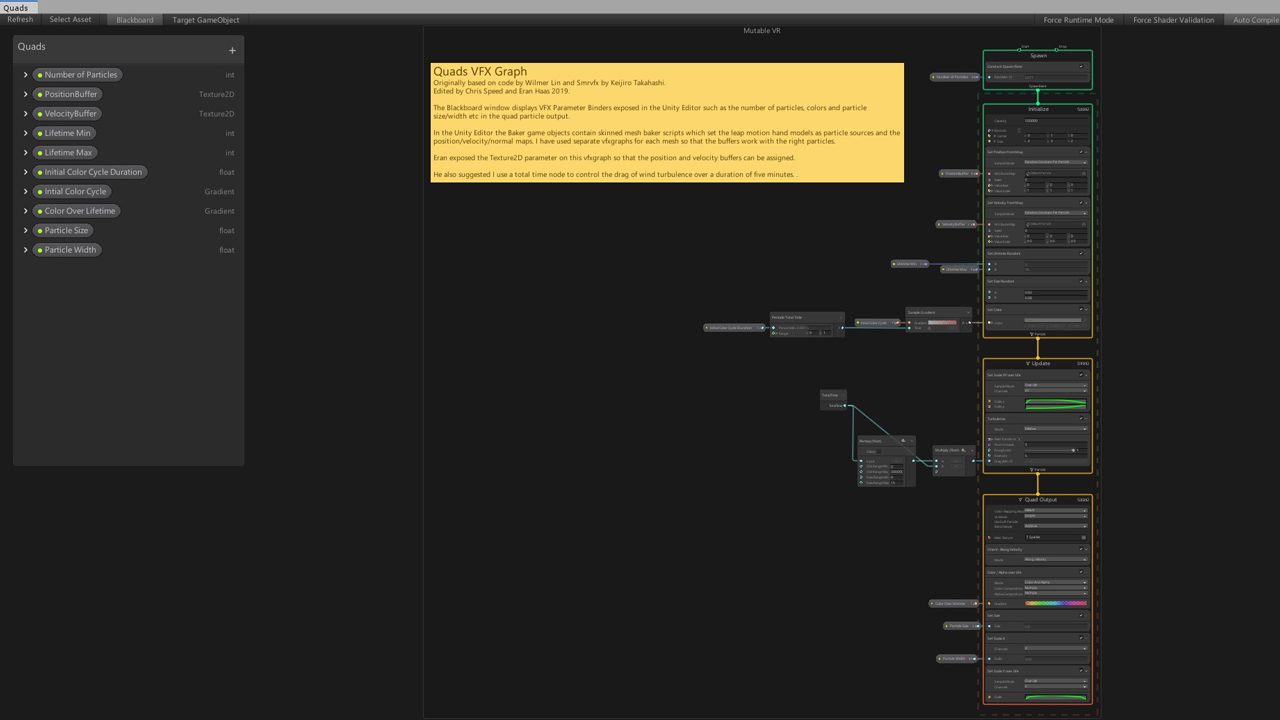

Upon Andy Lomas’s advice it seems that true emergence and complexity arises when reaching beyond one million particles. For my stochastic formations, I began to hard code compute shaders in HLSL however this was instantly deprecated with an update. To future proof I migrated to the new node based front end VFX Graph which Unity seems to be currently pushing for. Keijiro Takahashi’s package SMRVFX formed the basis of my project as it contained scripts which store skinned 3D meshes into a buffer and then use them as emitters. This created the particle hand effect I had envisioned. Through user testing it seemed that the leap motion (attached to the HTC Vive using a 3D printed mount) was more intuitive than the controllers, which lacked organic hand motion and thus broke plausibility illusion. I was one step closer to my goal of using hands as gestural interface, however I could only get one to work with the SMRVFX example. Luckily Eran Haas of Audiovisual Unity 3D allowed me to overcome this challenge in time. With two virtual hands functioning as a diffractive apparatus it seems the next step was to connect audio to the visual. Thomas Fredericks’s UnityOSC project once again proved to be very useful as it allowed me to send XYZ coordinates from the leap motion to receive in Max MSP.

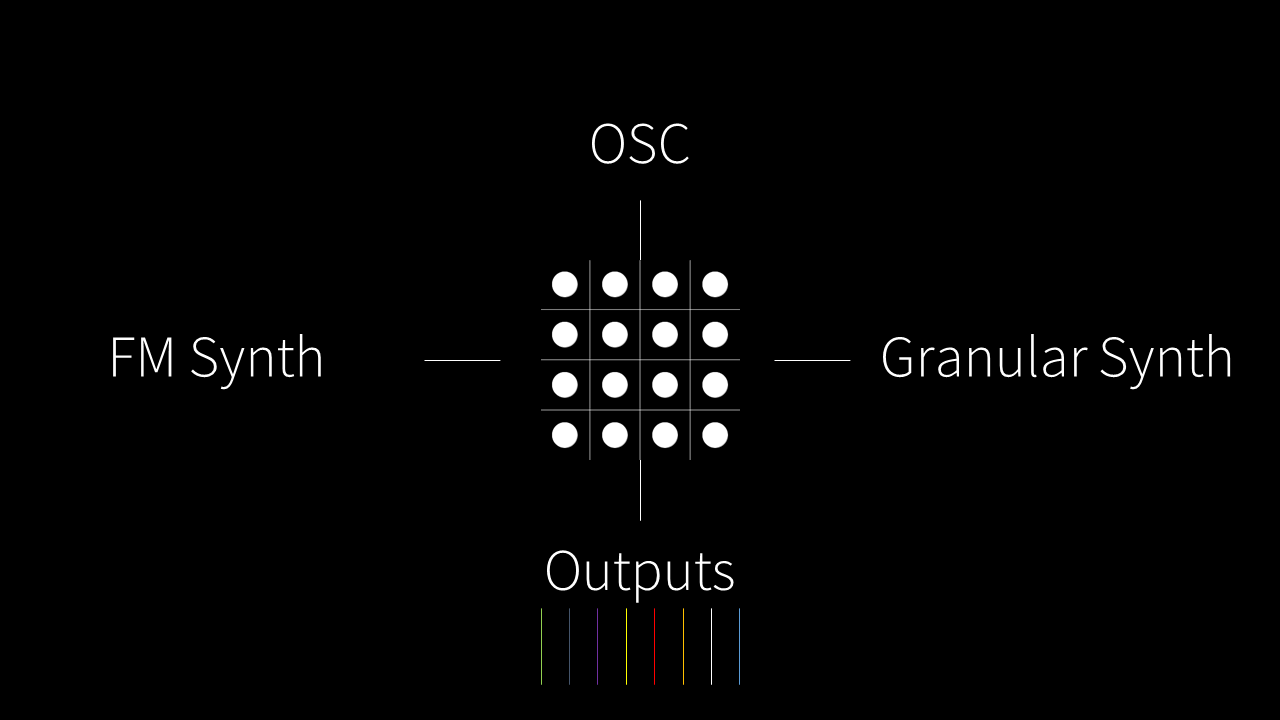

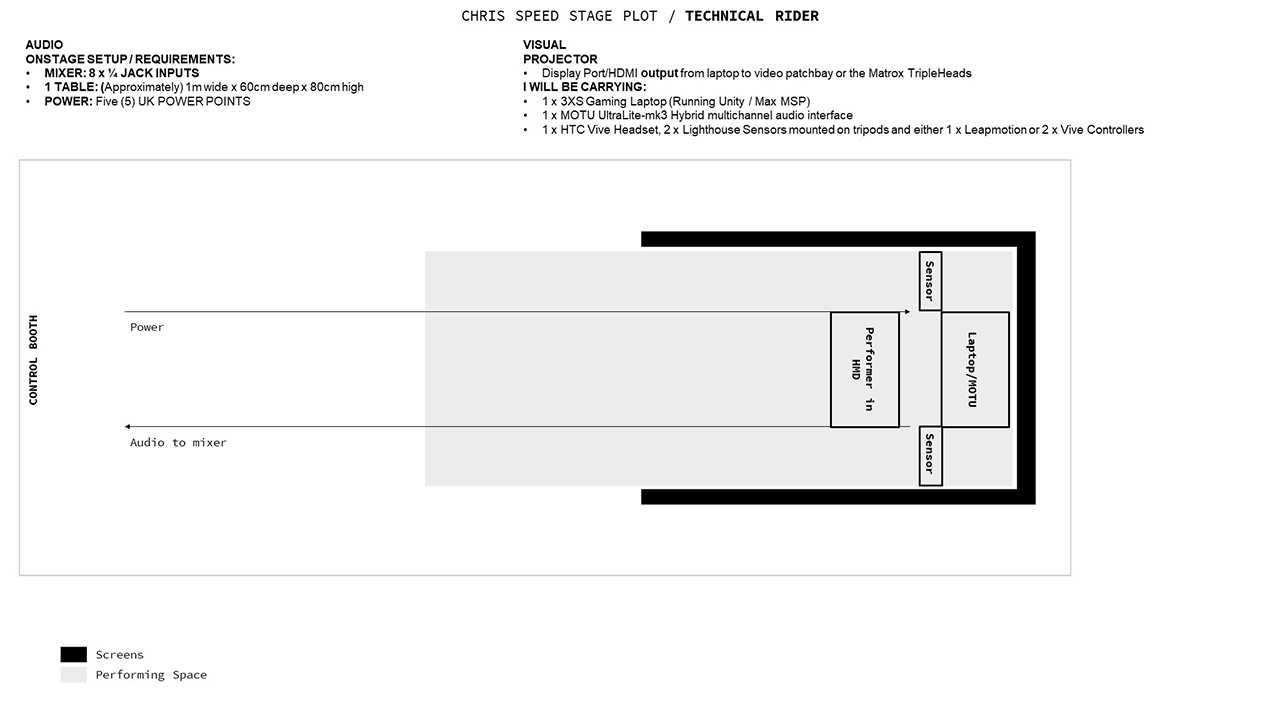

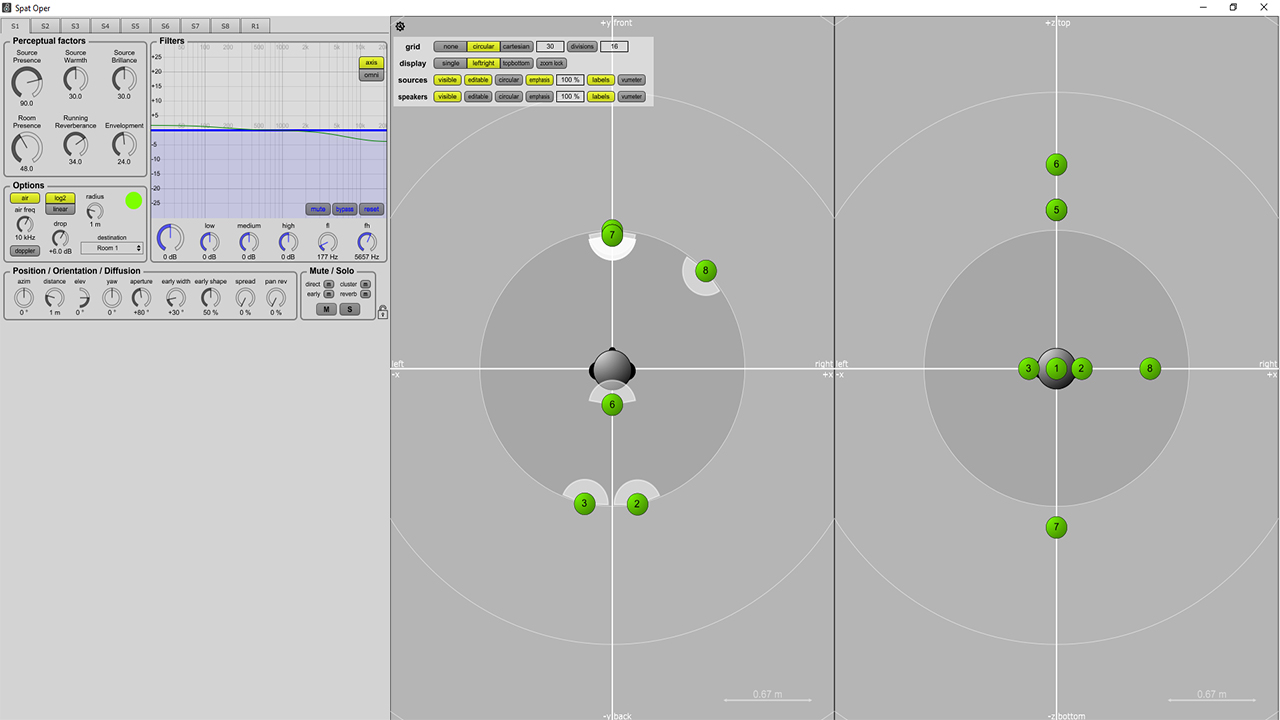

From here I worked primarily within Max, mapping the incoming position data to control sound parameters. Originally with this project, I considered keeping the entire system localised to Max MSP Jitter like the VR particle system granular synthesiser, Diffusion by Chris Vik. Unfortunately, it would not run on my machine so I thought it would be better to build my own from scratch. In terms of my patch, it consists of eight audio channels each containing different synthesis techniques such as karplus strong, frequency modulation and granulation. These patchers were based upon tutorials by Sam Tarakajian and my time spent auditing the BA Music Computing module here at Goldsmiths. With all the sounds prepared, I began to think about how to create spaces for them through convolution technologies. My research led me to HISSTools from University of Huddersfield which encapsulates complex reverb design into the simple multiconvolve~ external. But I also wanted to make my own impulse responses from scratch, so I used the department’s ultra-flat AKG C414 microphone to record a balloon popping in the St. James Hatcham Building. Collaborating with Taoran XU got me interested in the field of ambisonics and spatial sound which I quickly realised would benefit my project immensely. So, we worked together to create an acoustic model of the G05 space using Ircam’s Spat 5 external. This included measuring the distance between eight speakers, calculating the gains and delays of each by utilising the omnidirectionality of the C414 microphone placed within the centre of the space. Outputting from my multichannel MOTU audio interface, we experimented with spatial panning within the ambisonic stereo image and it yielded amazing results particularly with the Doppler effect.

Future development

To further develop my work, I would like to apply flocking behaviours to the particle simulations and sound as I feel combining the two would help create a more cohesive dynamic system. Implementing artificial intelligence could also be an interesting extension for this project such as using reinforcement learning or pose estimation models. Gaze detection also seems like a useful development in VR technology that could be worth exploring. I am excited to hopefully adapt this work to other immersive environments such as IX Symposium in Montreal.

Self evaluation

Overall, I am pleased with how my final project turned out as my refusal to artistically compromise has yielded worthwhile results. However Mutable VR has not been without its technical issues as this can be once again traced to the Matrox TripleHead setup in G05. I would loose fifteen to thirty minutes each day recalibrating my computer for output across three screens. This was due to the Matrox GXM application consistently sabotaging my display settings before showtime. In future I hope to avoid this level of technical uncertainty. This final project and the course overall has ultimately extended my technical skillset as a computational artist and allowed me to develop a deeper understanding of my artistic practice. As a final thank you, I will contribute to the community by eventually open sourcing my impulse responses and the Max patch I made with Taoran so it can give new students a headstart using spatial sound in SIML.

Special thanks to all the MA Computational Arts cohort 2017 – 2019 and the teachers who believed in me.

References

- Barad, K.M., (2007), Meeting the universe halfway : quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning, Durham: Duke University Press.

- Murray, C.D. & Sixsmith, J., (1999), “The Corporeal Body in Virtual Reality” , Ethos 27(3), 15–343.

- Ng, Jenna. (2010), “Derived embodiment: Interrogating posthuman identity through the digital avatar” , 2010 International Conference On Computer Design and Applications, 2, pp.V2–315-V2–318.

- Harker, Alexander and Tremblay, Pierre Alexandre (2012) The HISSTools Impulse Response Toolbox: Convolution for the Masses. In: ICMC 2012: Non-cochlear Sound. The International Computer Music Association, pp. 148-155. ISBN 9780984527410

- Norberg Festival 2019, ' ANRIKNINGSVERKET JOURNAL', vol. 1, https://norbergfestival.com/anrikningsverket-journal/

- Vik. Chris, Diffusion, (2019), GitHub repository, https://github.com/MaxVRAM/Diffusion

- Takahashi. Keijiro, Smrvfx, (2019), GitHub repository, https://github.com/keijiro/Smrvfx

- Fredericks. Thomas, UnityOSC, (2016), GitHub repository, https://github.com/thomasfredericks/UnityOSC

- Youtube, 2017, [Accessed 2019], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SaW5hZG8WLE

- Youtube, 2019, [Accessed 2019], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uAp7EtRNjMo

- Youtube, 2019, [Accessed 2019], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yb8JuFHJxQQ

- Youtube, 2010, [Accessed 2019], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5RYy8Cvgkqk

- Youtube, 2019, [Accessed 2019], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=keVozyJAIUM&list=PL-05SQhI5rIaX0Mlt0LHBc4QpJx5KtHhC

- Youtube, 2019, [Accessed 2019], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c1AoshXa5cQ&t=198s

- Youtube, 2016, [Accessed 2019], https://youtu.be/C9yj-J3V21o

- Youtube, 2019, [Accessed 2019], https://youtu.be/F_FhvxT5mLA

- Youtube, 2012, [Accessed 2019], https://youtu.be/tPvWiVaDpKQ

- Youtube, 2010, [Accessed 2019], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hYc2a1ONTck

- Youtube, 2019, [Accessed 2019], https://youtu.be/b5JYIvzBmZc