brackish

brackish is a kinetic sculpture and sound piece controlled in realtime by the River Thames

produced by: Elias Berkhout

Introduction

Deptford has been inextricably linked to the River Thames for many hundreds (if not thousands) of years, with the ups and downs of the river, and the industry associated with it, often mirrored in the vicissitudes of the area more broadly. brackish is intended to explore how the sounds of the multicultural and rapidly gentrifying Deptford of today can connect the suburb to its industrial and earlier history, with an accompanying transcription created in real time by water from the river itself over the course of the work’s exhibition.

Concept and background research

My early ideas for this final project had involved audio visualisation through use of lasers and other components, however, I found myself less engaged with the theoretical direction it was taking and decided to go back to the research I had undertaken in our Computational Arts-based Research & Theory classes earlier this year and find a way to work in concepts I had investigated there. As the work had initially been planned as a sound piece, I knew I wanted it to explore the sounds of Deptford and its connection to the Thames, with the types of sounds available controlled by the tide. Around this time I began reading more about the songlines, and I feel that it is important to point out here that my work is not intended as a songline, nor is it an attempt to make something even remotely resembling a songline. It is intended to be an exploration of the idea of the sound and the “music” of a place being able to serve a purpose similar to that of a map, whilst connecting that place’s past, present and future.

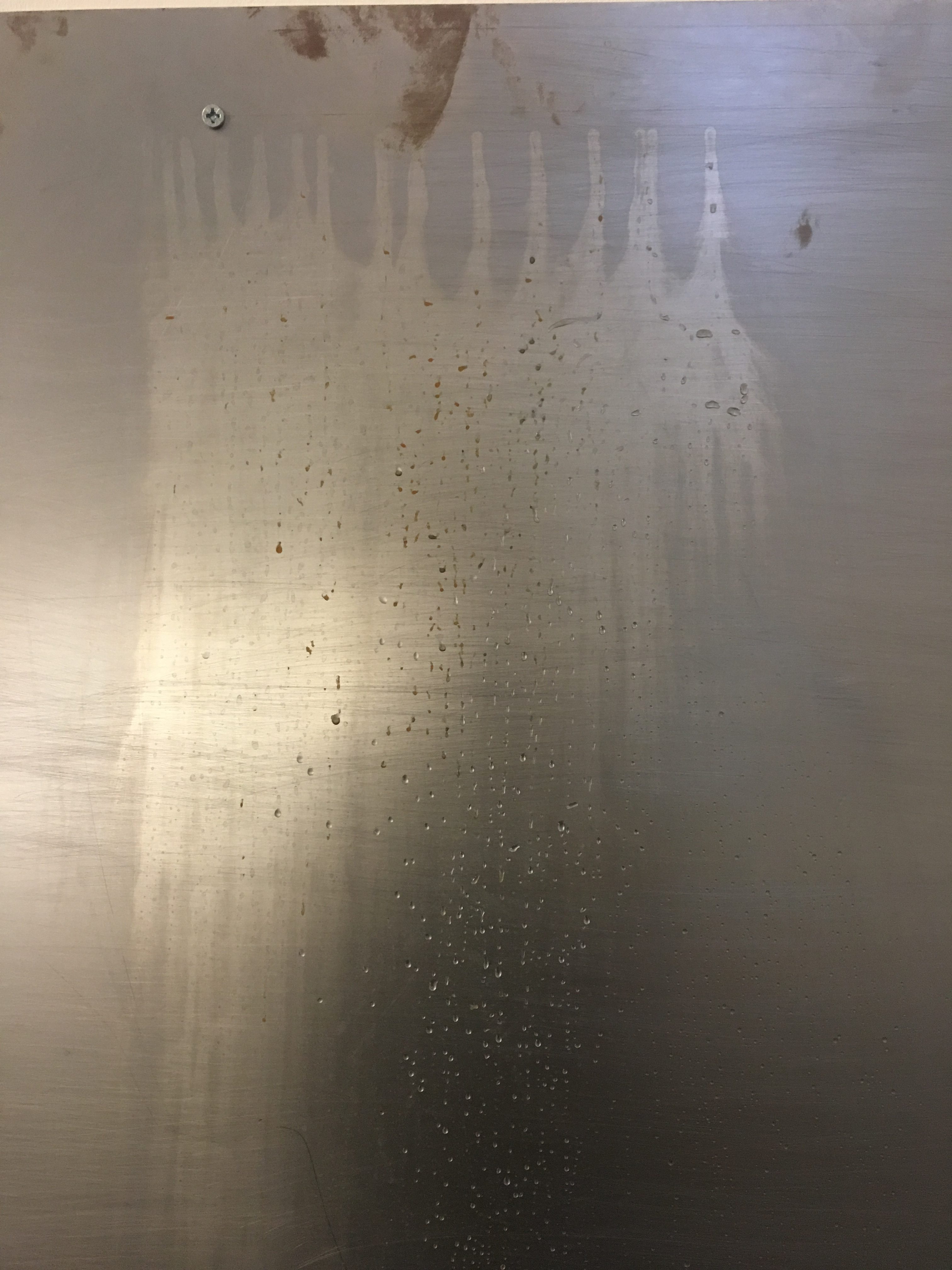

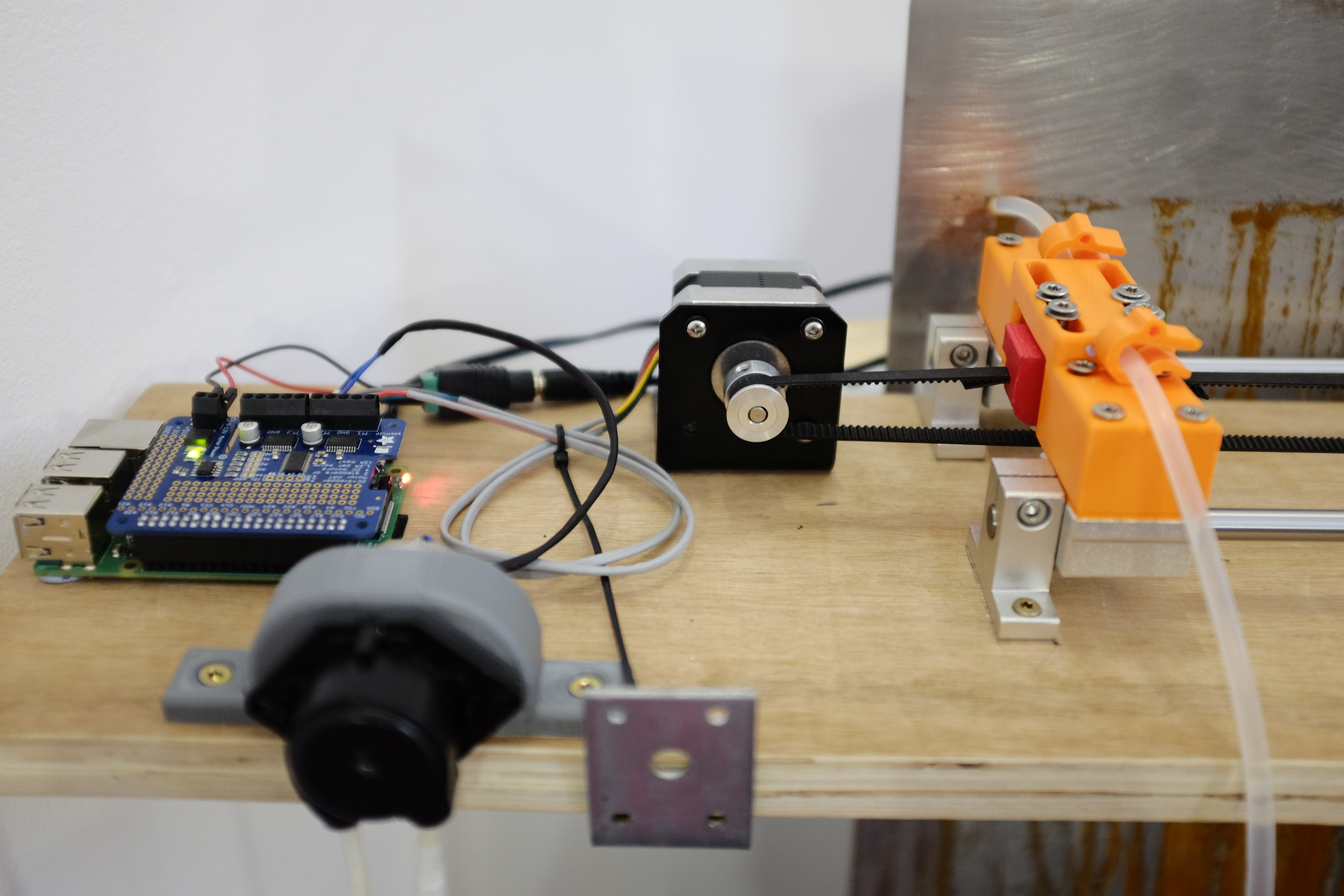

I wanted to create a transcription of the sounds of the piece that would change over the course of the exhibition, and the first substance I thought of using for this was the brackish water from the Thames. After that, I had to find something that would markedly change over a timeframe of three to four days. I looked into the most rust-prone steel and found an online retailer of mild steel where I could get some small pieces and commence testing. The steel had to be cleaned to remove its greasy protective film, and then scratched with rough sandpaper so as to provide horizontal striations for the water to collect in.

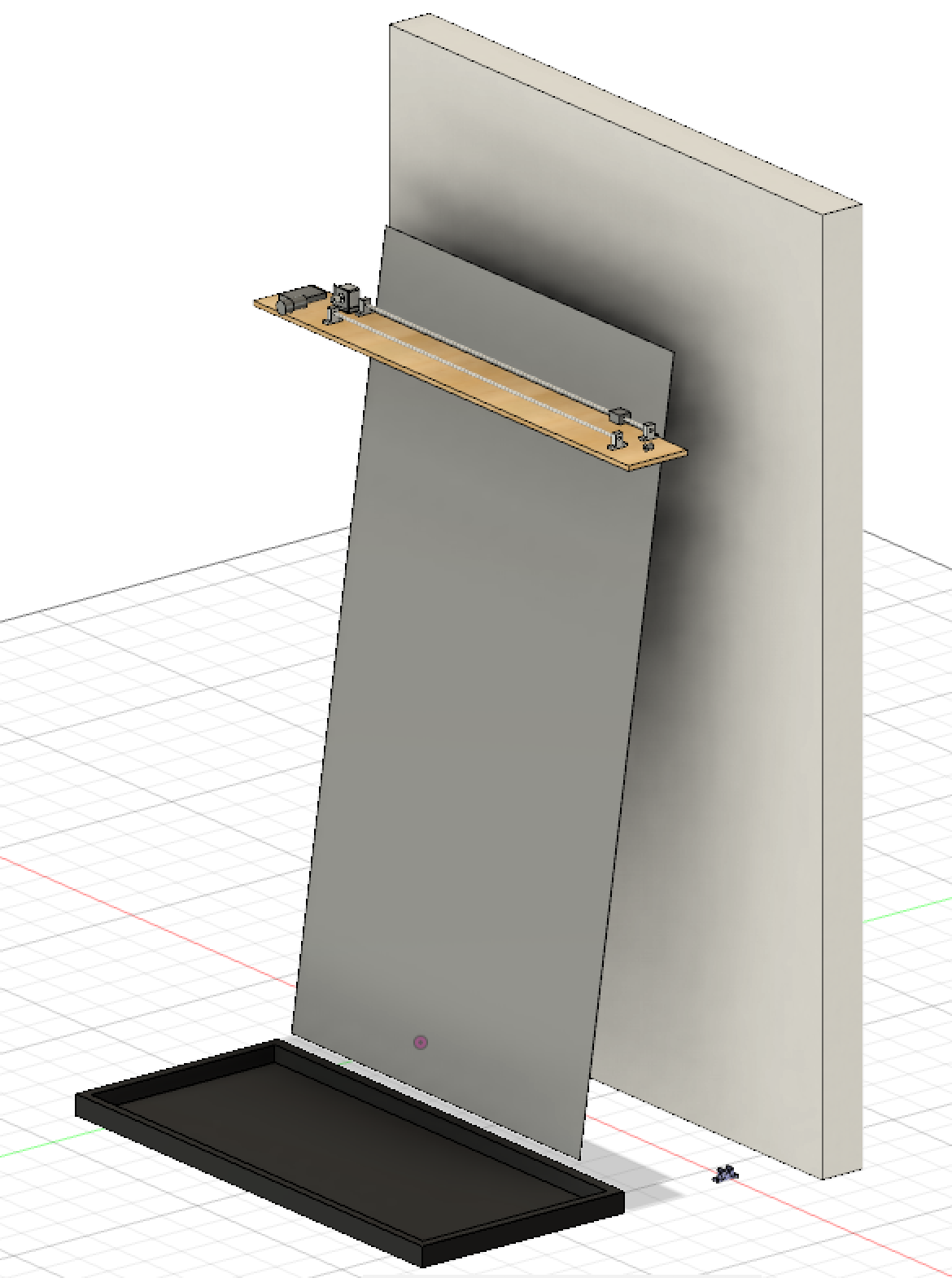

Visually, and in the way it was installed, the piece was heavily influenced by Robert Andrew, an Australian artist of Indigenous descent whose practice makes use of CNC-like machinery, and often liquids, to erode physical materials and reveal words or shapes over the course of weeks, months and even years. I was lucky enough to interview Robert for my research project and learn about his approach and the underpinnings of his practice. The installation of the piece was also inspired by some of the slower-moving pieces of Swiss artist Zimoun, and the subtle textural sounds created by his kinetic sculptures. Other important visual references came from the works of Richard Serra and Gerhard Richter.

Sonically, I was interested in exploring some of the broader ideas of Samson Young’s "Liquid Borders" (2012-14), by recording the sounds of a place and creating a visualisation or transcription after the fact, however, I was less interested in creating a musically readable transcription. Budhaditya Chattopadhyay’s Journal of Artistic Research article "Talking Field: Listening to the Troubled Site" (2015) was an important touchstone, both sonically and theoretically. My intention to emphasise the musicality of place by pulling musical frequencies out of recordings with resonant bandpass filters was inspired by his discussion of the role post-processing plays in the depiction of place through field recordings:

“The compositional strategy consisted of artistic interventions: taking intricate location-based multitrack digital field recordings and transforming these recognisable environmental sounds through studio processing. These artistic mediations diffused the recordings spatially into a blurry area between musical abstraction and recognisable sonic evidence of the site. The question is, how much spatial information, in terms of the recorded ambient sounds, was retained and how much artistic abstraction was deployed during production practice? This artistic process needs to be examined to better understand the nature of representation in field-recording-based sound artworks that intend to diegetically narrate sites...”

Technical

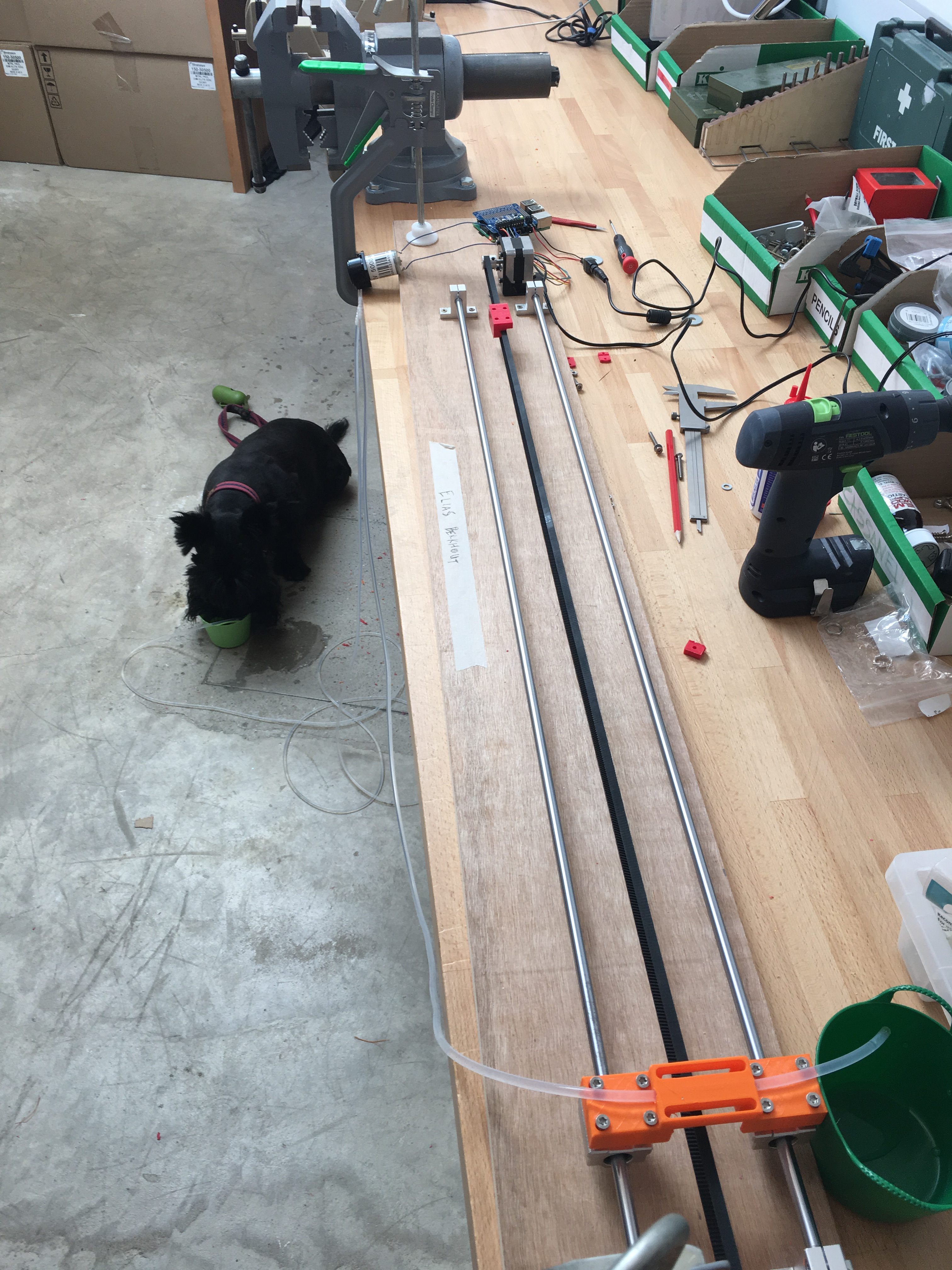

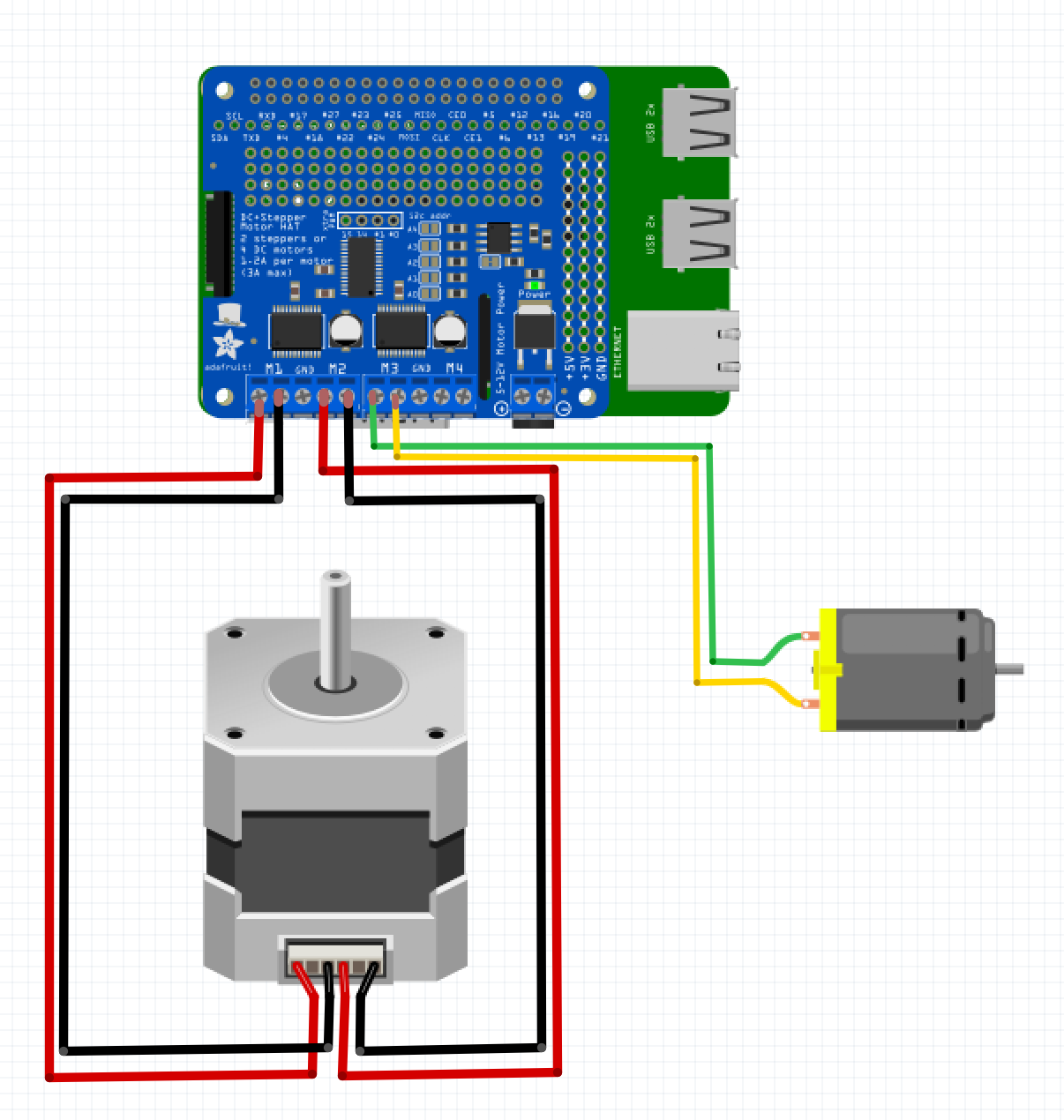

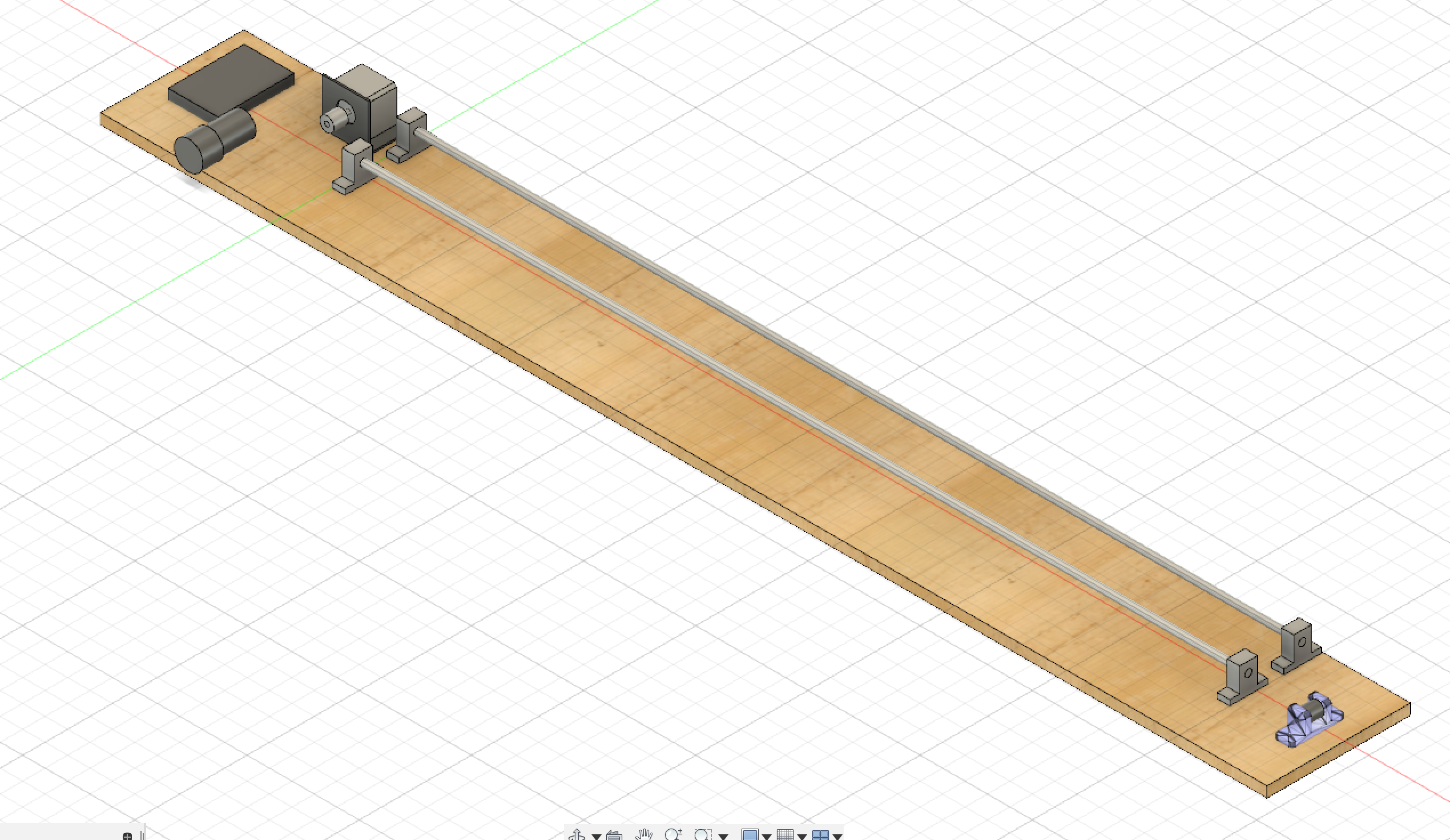

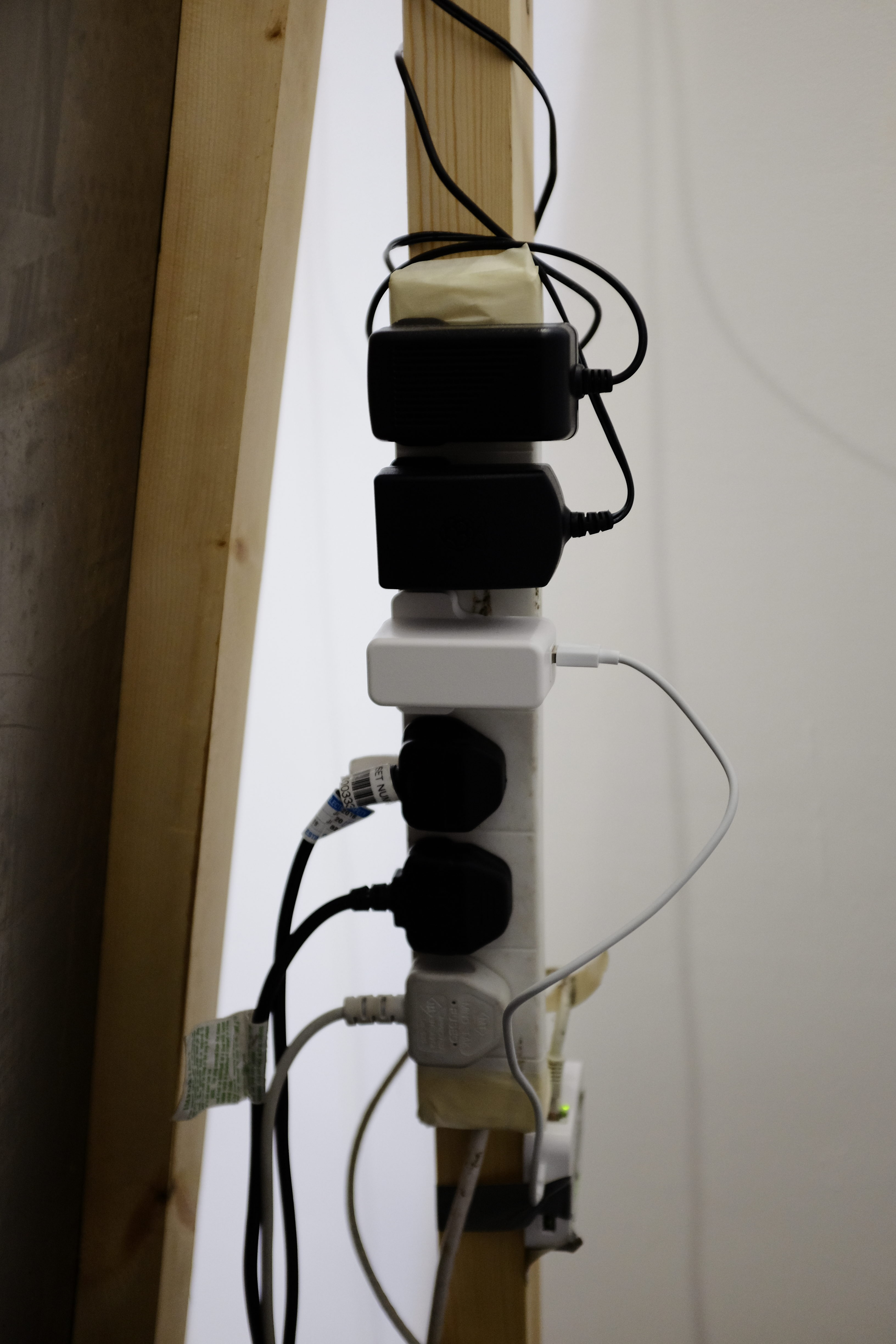

The motorised components of the piece were all controlled by a Raspberry Pi 3B+ and an Adafruit DC & Stepper MotorHAT. Other students regularly asked me why I decided against using an Arduino, and the reason was that I needed whatever was controlling the motors to check an online JSON file containing the live tide level, which an Arduino would not be able to do. I spent a long time researching rails, bearings, supports, timing belts, stepper motors and peristaltic pumps to make sure that the components would move at a sufficient pace, and that the pump would be able to pull water up nearly two metres from the tray located at the base of the steel sheet, whilst also embarking on my first foray into Python to read the data online and move the motors accordingly. After reading the tide level, the Raspberry Pi sent the current level from the JSON file to the computer playing the audio using the OSC messaging protocol.

This project also saw my first attempt at making a substantial generative sound piece in the audio programming environment Supercollider. Eli Fieldsteel’s youtube tutorials were an invaluable resource for me, and I made use of the layout from his “Composing A Piece” series in my project. This meant that the piece could have an individual event for each of the four tide levels – low, mid-low, mid-high and high tides – which was triggered when a relevant value was received from the Raspberry Pi over OSC. At low tide, sounds of people in and around Deptford market are heard alongside the sounds of industry and, rarely, some small snippets of sounds of the river. In contrast, at high tide, the vast majority of sounds heard are recordings of the river. In audio synthesis, when filters are pushed into self-resonance, they create sine waves of clearly perceivable pitch at their cutoff point. I used this technique to pull out musical content from the samples, creating generative chordal and melodic movement, and particularly liked the connection between the filter-generated sine wave melodies and the much slower sinusoidal movement of the tide. I also created a series of oneshot events which are randomly selected when Supercollider receives an OSC message, as an audible "alert" of sorts that the carriage is beginning to move.

I had hoped to run the audio from a separate Raspberry Pi, and had gone so far as to purchase a high quality Pisound audio hat and install all the necessary software, however, the near-1GB collection of field recordings loaded into buffers in my Supercollider project proved to be too much for the Pi to handle, so this ended up being run on an older 2013 MacBook Pro with audio being sent to the speakers through a Keith McMillen K-Mix audio interface.

About a month before the exhibition I encountered a raft of mysterious wifi connectivity issues, where I would receive a handful of different errors stemming from accessing the website where the JSON file is stored. I changed my wifi router, I signed up to a different API where tidal data from around the UK is posted, and I emailed a data.gov email address to find out if I had been blocked from accessing the information. The next day I moved from the hatchlab into G11 and all my issues miraculously disappeared. As this was getting closer to the show, I assume this had something to do with a larger number of students in the hatchlab using the G11 wifi, but whatever it was, after two days of struggling to fix it, or find alternative means to access the data, moving into G11 fixed everything.

I used Autodesk’s Fusion360 software to plan the placement of components and also to design the frame on which the pieces of steel rested. Having never built a timber structure like that, having the Fusion sketches was immensely helpful for the design and planning of both the frame and the plank upon which the components were mounted.

Future development

In future I would love to create a much larger iteration of the piece, taking it from its current state at one metre wide to five or even ten metre wide versions. This would allow the piece to develop over a much longer time period as the space between the readings would get filled in by subsequent readings more slowly. With more time and money, I would like to make the plank on which the components are mounted a little more polished and thought-out, in addition to using higher quality components so as to have the carriage move more smoothly, and possibly more quickly. Having said that, I do feel that its slow speed suits the timescale at which the piece operates. I am torn between liking the garish orange of the 3D printed parts I used (seen by one student as reminiscent of the buoys along the Thames), or thinking they should be a more muted colour so as to not draw attention to themselves. This is another aspect I'd like to experiment with when the piece is shown next. Further funding and time would also give me the opportunity to explore the possibilities of the reflecting pool part of the work, by creating a more sculptural and materially relevant tank or tray in which to catch the water, possibly experimenting with different shapes and sizes to maximise the impact of the reflection of the steel and the ripples created by the water droplets.

Self evaluation

I was incredibly happy with how the project turned out overall. I found the sound part to be very meditative, with a good compromise between recognisable sounds of Deptford, with subtle musicality worked in to maintain the interest of viewers between tidal readings. Running the audio from a second Raspberry Pi did not work at all, and this is something I would like to experiment with further as the piece develops in the future. I had a number of people tell me that they would be interested in seeing different rivers, which sort of loses the piece’s original idea of an exploration of Deptford, rather than the river itself, but I do see that as an interesting way to continue the piece moving forward. If I do explore other rivers or waterways, I would still like the piece to be more about a place and its connection to any given river than about the river itself. As above, I would have liked for the motorised parts to be mounted on something that looked a little more polished and artwork-like in itself, but this is something that I aim to develop in the future.

References

Source code available at: https://github.com/ebkt/River

Chattopadhyay, Budhaditya. Taking Field: Listening to the Troubled Site [http://www.jar-online.net/talking-field-listening-to-the-troubled-site/]

Fieldsteel, Eli. SuperCollider Tutorials [https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLPYzvS8A_rTaNDweXe6PX4CXSGq4iEWYC]

Nouri, Daniel. Carriers and Modulators [http://danielnouri.org/docs/SuperColliderHelp/Tutorials/Mark_Polishook_tutorial/Synthesis/14_Frequency_modulation.html]

[https://learn.adafruit.com/adafruit-dc-and-stepper-motor-hat-for-raspberry-pi?view=all]

https://www.thismusicisfalse.com/liquid-borders/

https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:2347849