Understanding Black British Information and Communication Technology: The Metamorphosis of Storytelling Into The Digital Sphere

Produced By: Omolara Aneke

Introduction

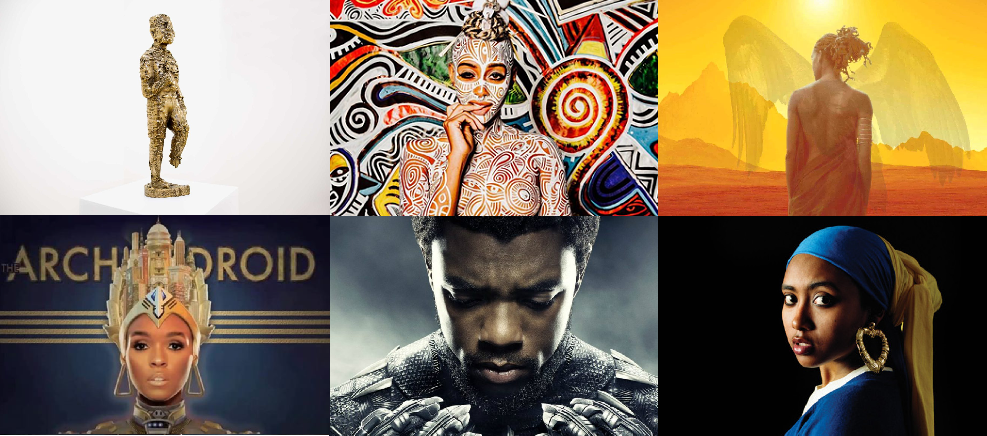

Figure 1:Clockwise from top left: Sanford Bigger’s “Bam”; a bodypainting work by Laolu Senbanjo; the cover of Nnedi Okorafor’s Who Fears Death; Janelle Monae’s album The ArchAndroid; poster from Black Panther; Awol Erizku’s “Girl With A Bamboo Earring”, African Arguments, 2018.

Black British Feminism

There is no fixed sense of what it means to Black (Dzimwasha, 2014; Emejulu, Sobande, 2019). It is a socially constructed term used to categorise darker skin complexions; specific meanings will vary depending on geographic location or context (Dzimwasha, 2014; Emejulu, Sobande,2019). In addition, an issue arises in some Black Feminist spaces when the meaning of Black predominantly focuses on the racial, gender and intersectional politics of Black North American Women (Dzimwasha,2014; Emejulu, Sobande,2019). The United States is a global powerhouse that ‘imposes and transmits its values and cultures across the world’ (Emejulu, Sobande,2019, Turman, 2015). It has been suggested that Black British people grow up on the side of Blackness that favours the African American Experience (Dzimwasha, 2014, Emejulu, Sobande,2019). Put in another way, the internet birthed networks and connections that zip global influences and cultural references back and forth, with Black North American cultural production taking a front seat in the representation of Blackness (Emejulu, Sobande,2019). Emejulu and Sobande(2019) back up this sentiment and argue that ‘when we think about Black feminist theory and activism, we look to the Black American experience and seek to universalise and apply it to Europe’. Consider the example of Black Feminist scholars Bell Hooks and Patricia Hill Collins or Black Civil Rights heroes Rosa Parks and Angela Davis to see the impact Black North Americans have had on Black scholarship or Black activism (Dzimwasha,2014, Emejulu, Sobande,2019). The same ‘popular knowledge’ production is not extended to Black activists in the diaspora that have faced or are facing similar challenges (Emejulu, Sobande,2019).

Even with the ‘conscious construction of sameness’, Blackness in this capacity rarely speaks to my specific experience as a Black British feminist of African decent (Mirza,1997). Even with this acknowledgement, it is important not to deny or speak ill of the Black Feminist Movement, the many triumphs or the key players. It is too easy to separate the plights in favour of one claiming a ‘privileged standpoint’ or ‘unique consciousness’ over the other (Mirza, 1997). Contrastingly, the aim is to build upon the blocks already laid giving strength to a multiplicity of perspectives the challenge ‘normative discourse’ (Emejulu, Sobande, Obasi ,2019; Mirza, 1997). Similar to the common critique Black feminists have with Feminism and its preoccupation with White women (Mirza, 1997).

Research

Upon searching for academic materials regarding Black British Feminist technoscience, I was struck by the lack of resources available that at the very least addressed Black British Feminism. I was met with a lengthy search that led me to two collections of essays, one published in 1997 and the other in 2019. The Black British Feminist Reader (1997) explores postmodern themes of gender and race exclusion that have been integral in the scholarship of Black British Feminist identity (Mirza, 1997). Exist to Resist (2019) is similar to the aforementioned book, but with a broader scope illuminating the experiences of Black women in Europe. Many of the names in the reference list for Exist to Resist(2019) are in the Black British Feminist Reader(1997), essentially acting as an updated and more inclusive version. To take it further, research into Black British interactions with technology, among other things, are missing from research literature. In other words, little visible academic work has been done to theorise how Black British identity plays out in the new digital age. With resurgent movements like AF drawing attention to Black technoscience, again, African American contributions flood.

This research project aims to explore a void in scholarship that examines the above topics and is a small piece of a larger study of Digital Archiving. I will use both books mentioned above and key aspects of the AF movement as a framework for using the digital to preserve and archive oral stories (Groenewald, 2003). This gives birth to an exploration into crossing generational boundaries. Whereas in Africa, villages thrive on multigenerational interactions to nurture communities, I want to use technology to aid in the passing on of stories, codes and values in Black British spaces where we live more disconnected lives (Groenewald, 2003). The introduction of new media and information and communication technology allows us to move beyond texts in history projects and utilise a variety of digital formats (Klaebe et al.,2007; Oral History and technology, 2020). As a result, we can seamlessly carry history around with us; our phones and tablets are constantly connected to a wealth of different information sources, especially if you know where to look (Klaebe et al.,2007; Oral History and technology, 2020)

Heavily relying on memory, Oral stories are an invaluable primary source that allows us deeper insight into the feelings and desires of people(Tobbell, 2016; British Library, 2020; Desai, 2001). The above is true for African societies with many concerned with Storytelling as a way to intuitively control the narrative (Tuwe,2015; Layton ,1994). For centuries, even before reading and writing were developed, Africans used folklore and mythology as a way to transmit knowledge and information across generations (Tuwe,2015; Layton ,1994). This is an instance of us telling our own narratives for us in its purest form(Mirza, 1997). The most respected person in traditional African society was the Griot, an oral historian and educator responsible for maintaining the connection between the past and the present by keeping and these telling stories (Banks-Wallace, 2002). With words held to such high regard, it is no surprise that naming practices are not taken lightly in many African societies (Groenewald, 2003). For example, names hold weight as they are seen as mini prayers; to constantly verbalise these names is to take part in affirmations, to give thanks or to put into the earth for manifestation (Groenewald, 2003; Layton ,1994). My name Omolara in Yoruba loosely translates to children (new life and blessings)will surround me, this is a statement declaring that my mother will live a blessed life.

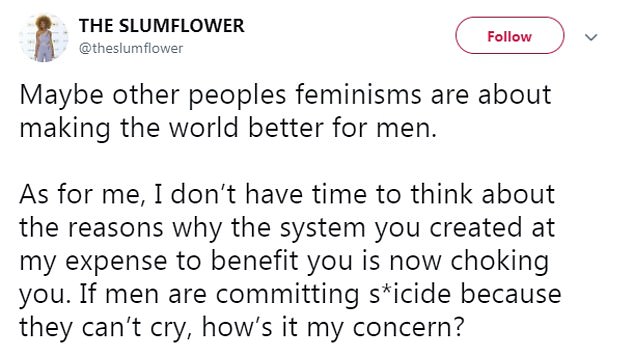

Figure 2: Untitled, Screen shot of a tweet from Twitter via Eighties Kid, 2019

Figure 3: Untitled, Screen shot of a tweet and an image from Twitter via Eighties Kid, 2019

Black Women in the Digital Space

Few attempts have been made to digitally archive and preserve Black British feminist history with the most notable attempts coming from the Black cultural archive (BCA) in Brixton (Smyth, 2017). They are a hub dedicated to teaching, celebrating and collecting all things Afro-Caribbean in Britain (Black Cultural Archives, 2020). Feeling excluded by mainstream historical gatekeepers, a project Titled Oral Histories of the Black Women’s Movement: The Heart of the Race was launched in 2010 (Smyth, 2017). It is comprised of a collection of memories working to counter and make visible the experiences and contributions of women of African, Asian and Caribbean descent in the 1970s (Smyth, 2017). The BCA digital committee put the oral recordings on their website in an attempt to garner more awareness and reach more people than their physical building in Brixton would attract.

Portals into the digital space allow for Black women to engage with other Black women bypassing the need for mainstream outlets to house, promote or facilitate them (Emejulu et al. ,2019). With said portals becoming more universally affordable and accessible, Black women can participate in both the production and the usage of social media to curate identity (Emejulu et al. ,2019). Anyone who has access to the internet can take part in the sharing of information whether that be archiving or relaying a message (Emejulu et al. ,2019).

In recent years, Black Feminist bloggers such as Reni Eddo-Lodge (Figure 2/Figure 3, Eighties Kid, 2019) and Chidera Eggerue have published British culturally acclaimed books stemming from the success of their online platforms (Emejulu et al. ,2019). Wanting to amalgamate her heritage with her feminist view point, Eggerue wrote a book titled What a Time to be Alone. Passing on Igbo Proverbs taught to her by her Nigerian mother, she relates each to everyday contemporary British life as a woman in her twenties (Berrington, 2018). Eggerue is of the belief that her success comes from exposing herself bare as a subject for scrutiny to allow Black women viewers the chance to connect and say 'Oh my god, that’s exactly how I feel but I just didn’t know how to say it’ (Berrington, 2018).

Using established modes of communication to deliver a message is a start (Emejulu et al. ,2019). But there is a need for our own information communication structures that allow us to create search engines, metadata tags, public information resources and algorithms in favour of the Black Liberation Movement (Emejulu et al. ,2019). To illustrate the point further, take Oscars and award shows of the like for example (Ugwe,2020). The hashtag #OscarSoWhite was created to draw attention to the lack of diversity in Hollywood (Ugwe,2020). In response to the hashtag, it is argued that we need to shift the admiration and longing from organisations where diversity is an ongoing struggle to award shows created by Black people where you can celebrate our own narratives. Similarly, writers like Eddo-Lodge and Eggerue are among the list of creators that are popular in talk but not as popular in internet search unless you know exactly who you are looking for. When Google searching Eddo-Lodges name you are recommended 12 other people, of which only one was another Black British woman writing from a similar perspective, June Sarpong. The rest were 2 women of mixed Black heritage, 3 Black women from Germany, 3 White women and 3 Black men. In other words, searching for specific content is made harder as there a lack of invested interest in diversity and increased visibility.

It is worth mentioning the critique associated with the digital space. The ‘values and codes’ produced and ascribed by the ‘hegemonic global power’, the United States, play a part in the discrimination ‘embedded in computer code’ (Noble, 2018; Emejulu, Sobande,2019; Turman, 2015). Safiyah Noble defends the view that the internet sphere is not a neutral playing ground, in fact, the algorithms people assume to be without bias, swing in favour of white males that write them. In her book, Power of Algorithms, Noble explains that ‘English-speaking internet users, content providers, policy makers, and designers’ assign their while male perspective as the norm ‘redistributing cultural resources along racial lines’ (Noble, 2016). In other words, the internet works on a multitude of levels, as well as aiding the transfer of communication and information it can also be an oppressive site reenacting offline race relation through our screens(Noble, 2016, Noble, 2018). Noble labels this algorithmic bias as ‘technological redlining’ (Noble, 2018).

Methodology

Now more than ever with the pandemic causing great devastation,preservation and continuation barge to the forefront. Taking the time to record, give meaning to or mark memories for future generations has been a way for many family to pass on knowledge through time unconsciously and consciously. New media tools like Instagram do similar this for a new generation allowing you to digitally capture and signify memories with a post. In this same vain and that of the bloggers marking a time in history that will stay on the blogshphere for years to come, I sought to do the same for my family. Further mark, point out and give light to my history orally. With my Nana’s mortality looming due to unforeseen circumstances, a big chunk of my history goes undocumented from that branch level and above. As she is currently under the weather I sent her a revised version of the question I wanted to ask making them more basic and easy to answer if she fell strong enough. In light of the situation I utilised the people at my disposal. I started by holding an individual semi-structured interview with my mother. I prepared a set of topics and questions for her to respond to and provided her with the list as to not surprise or catch her off guard. I used the voice recording application that came with the android phone, this allowed me to have audio files as an output that can be sent around or manipulated on the phone directly or on a computer. To create a friendly, non-threatening atmosphere I suggested we sit in her bedroom. She sat at the head of the bed sitting up and I sat at the tail end laying down, a set up we are overly familiar with. I propped up the recording device on the bed in between us subtlety covered by a blanket so it’s not in her view constantly reminding her that we are recording. The purpose of holding this informal one to one session was to shift the role of Grior, in this loose context, from human to computer transferring the responsibility of keeper to the digital sphere.

As a starting point to archiving parts of my family history, I started by asking my Mother to tell me about my Grandmother, Hannah Aina Olyouriju (her Mother). She proceeded to tell me about my Grandmother's childhood growing up in Ute, Nigeria, a small rural village 45 minutes outside of the capital city. In a time where polygamy was a big part of the culture, my Grandmother was raised by a wife she thought was her mother only to find out later on who her birth mother really was.

“My mum was a product of paligamy… my dad used to say that as an excuse as to why she needed to put up with the stuff he was doing. She had many siblings from her own mum, but there was a wife who had no children. She did not know until late into her teens that the woman she called mum actually wasn't her biological mum. The person who was actually her real mum, she thought was one of the wives of the compound, they all lived in a compound together . this particular wife didn't have any children she took one of the other wives children as somee that she, on the day to day basis, raised. My mums mum has a few of them but from what i understand she wasn't the strongest of them and so having someone else do the day to day for one of your children is just reliving you of having to do it. My mum was raised by this particular women but she never knew. She always said that when she found out she was a little annoyed because she would she the way the women who raised her treated her biological mum and she didn't like it. But she was unaware of the politics behind it. From Then on she stopped referring to the women as mum.”

Prompted by a story about moving from Nigeria to England in December 1959, my Mother proceeded to tell me about a family structure she thought to be popular among Yoruba people who moved to England to work. Due to the busy work schedule my mother and her siblings were sent to a nanny.

They found the Goldsmiths from a recommendation… They took Kunmbi there and she settled in. Teju was born in April, my dad was back in nigeria by september. After breast feeding she then joined kumbi at the goldsmiths. When the big thing happened one was 10 one was 11. Her other biggest mistake was trusting the goldsmiths ... She started to behave like they were sisters. They would be there [sussex] during term time, they would come home during the holidays. There were many times when mrs. Goldsmiths would come down with them and they would stay in [our] house. I remember telling her not to get so close… but because they never believed in a million years that she would be capable of doing what she did they didn’t plan [ahead]. They thought it would be nothing to say they are 11 and 10 now, let them stay at home. When the holiday was done she got a phone call [from a lawyer] saying that she couldn't take them anywhere, they are wards of the court and there is going to be a court case. My father found his way to the UK when he was told.The idea was for him to come, buy [plane] tickets and go back to nigeria. But when he got here he was pissed and he started to run his mouth, one of the things he did was tell them that he was going to take them to nigeria. So they [goldsmiths] immediately went to court to have their passports removed. And bang goes that plan of his. There was nothing for them to do but go through the court system.

I received a message from my Uncle with 3 voice recordings and a note that said "From Nana".I was shocked and excited to hear what my Nana has to say. She spoke about her childhood, the various marriage proposals, meeting my grandfather, life in Britain after the war in Nigeria and various other things.

Grandfather left Nigeria to study in England in September 1962, then we had 3 children. I ad to look after them. My Father and Mother in law died in 1962, the same year. I left Nigeria in December 1964 to join IG, my husband, in London. I didn't want to come, i didn't want to leave my children on their own or with strangers. When I arrived in London IG was still at school, I went to work to sustain our lives and sent fund home to the children. It was a very tough and difficult life but very enjoyable depending on how one sees it. We lived in one room with a cooker stuck in the corner of the room. Or we shared a kitchen and bathroom with others with resultant problems. No central heating, but cans of smelling paraffin heaters that heat the room up. It was grim, but we survived.

link to artists who use oral stories in their artistic practices.

Conclusion

As we move forward with the awareness that delay could be detrimental, we should take the time to archive on both an individual and communal level. Starting with the individual level and utilising the things within our means, the act of self-archiving can become an easier task with digital tools. For many living now, self-documentation is part of some of our social lives through social media platforms; we can document thoughts or capture memories so the years to come will benefit from the cultural production already in the digital sphere. As this is not the case for the previous generations, active effort needs to be put into preserving the past. This can be done in a number of ways from scanning in pictures and documents to recording stories and conversations. Moving to a communal level work, there have been few documented attempts to form Black British Feminist organisations, and this is urgently needed. Such an organisation would be in a position to offer a historical intersectional perspective similar to the Oral Histories of the Black Women’s Movement: The Heart of the Race project by the BCA. Another aspect of this organisation’s work would be to challenge Britain’s mainstream history and its teaching to include the multiple heritages of its citizens in the UK.

link to extened afrofutrism research

Annotated Bibliography

Mirza, H. S. (ed.) (1997) Black British Feminist Reader.pdf. first. London ; New York: Routledge.

This books seeks to contextualise the Black British Feminist experience during the 1980’s soley from the britsh standpoint. Through a series of essays, autobiographies and reflections this book documents the different racialised processes of conscious awakenings where your skin becomes the defining factor in the curation of identity. It aims to challenge hegemonic patriarchal discourse of colonial and now postcolonial times in feminist theory and politics through the exploraion of race, gender and class.Mirza describes a state of becoming that is living in Britain and being Black; having your skin be a signifier of difference. It’s unique comes into play via its tunnel visioned perspective as it was one of few Black British academic texts. It concludes that even with the work going on to critically review Black life there is a way to go. This is echoed by the structure of the book, Split into 3 sections starting with ‘Shaping the Debate’, ‘Defining our Space’ and ‘Changing our Place’. The later two sections focus on ways of moving the cause forward.

Noble, S. U. (2018b) ‘Introduction: The Power of Algorithms’, in Algorithms of Oppression. Pluto Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pwt9w5.4 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

A Future for Intersectional Black Feminist Technology Studies was intended to add to the discusion around informtion and comuicaion technogly and it’s bias to towards the tastemakes and software creators that are usually white and male. Noble accknwledges the power of he internet and the potential role can play in social liberation and awaresness whilst remiding us of the social injustices mirrored online. Being that Noble’s perspective is North American, i tread carfully drawing direct paralells and assuming a one size fits all startegy. However it’s relevance is heighten becasue little visible work has been done to theorise the black british feminst interactions with technogly. In addition to that, the bittersweet globalisation that gives us access into communtiyies around the globe also works to play out these same social injustices not only on north american technogloyies but also those in the UK and others who have access to the same technolgoies. Noble’s main conclusion is that intersectionality in regards to the internet and dgitieal studies provides us with the tools to analyise racism, sexism, surveillance and control online.

Smyth, H. K. (2019) ‘“Oral Histories of the Black Women’s Movement: The Heart of the Race.” Reflections on a secondment to the Black Cultural Archives.’, p. 9.

‘Oral Histories of the Black Women’s Movement: The Heart of the Race.’ Reflections on a secondment to the Black Cultural Archives (BCA) aims to detail the process of putting together, arciving and exhibiting history through her time working at the BCA. Centered around the expeinces of the Black Women’s Movement in Britain, women of African, Asian and Caribbean descent oralised their encounters with racism and sexism. Smyth seeks to hightlight the importance of archiving in relation to reclaiming and remaking history. In addition, it provides a framework for other people are also intersting in archiving history where it be oral stories or otherwise.

References

Abrams, L. (2010) Oral history theory. London ; New York, NY: Routledge.

African Arguments (2018) ‘This is Afrofuturism’, African Arguments, 6 March. Available at: https://africanarguments.org/2018/03/06/this-is-afrofuturism/ (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Airoldi, M. (2018) ‘Ethnography and the digital fields of social media’, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(6), pp. 661–673. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2018.1465622.

Arai, T. (no date) Artist Statement, Tomie Arai. Available at: http://tomiearai.com/process (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

BBC (no date) BBC - Alt History - Episode guide, BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p07dkx93/episodes/guide (Accessed: 2 March 2020).

Beckles-Raymond, G. (2019) ‘Revisiting the Home as a Site of Freedom and Resistance’, in Emejulu, A. and Sobande, F. (eds) To Exist is to Resist. Pluto Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvg8p6cc.10 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Berrington, K. (2018) Chidera Eggerue On Being A Force For Change, British Vogue. Available at: https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/chidera-eggerue-interview (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Black Cultral Archives (2020) About, Black Cultural Archives. Available at: https://blackculturalarchives.org/about (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Black Enterprise (2018) What is Afrofuturism? Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AgXujySEuIE (Accessed: 2 March 2020).

Black Speculative Arts Movement (no date) Black Speculative Arts Movement, Black Speculative Arts Movement. Available at: https://www.bsam-art.com (Accessed: 2 March 2020).

Boyd, N. A. (2008) ‘Who Is the Subject?: Queer Theory Meets Oral History’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, 17(2), pp. 177–189. doi: 10.1353/sex.0.0009.

British Library (no date) Art - Oral history | British Library - Sounds, British Library. Available at: https://sounds.bl.uk/Oral-history/Art (Accessed: 14 March 2020).

Burin, Y. and Sowinski, E. A. (2014) ‘sister to sister: developing a black British feminist archival consciousness’, Feminist Review, 108(1), pp. 112–119. doi: 10.1057/fr.2014.24.

Burn, A. (2014) ‘Digital Aletheia: technology, culture and the arts in education’, The Routledge Companion to Music, Technology & Education. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324719000_Digital_Aletheia_technology_culture_and_the_arts_in_education (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Caliandro, A. (2018) ‘Digital Methods for Ethnography: Analytical Concepts for Ethnographers Exploring Social Media Environments’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. SAGE Publications Inc, 47(5), pp. 551–578. doi: 10.1177/0891241617702960.

CNN, A. A. (no date) How ‘Black Panther’ costume designer Ruth E. Carter wove an Afrofuturist fantasy, CNN. Available at: https://www.cnn.com/style/article/black-panther-costumes-ruth-e-carter/index.html (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Creative time (no date) The Domestic Violence Milk Carton Project, Creative Time. Available at: http://creativetime.org/projects/the-domestic-violence-milk-carton-project/ (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Cruel Ironies Collective (2019) ‘Cruel Ironies: The Afterlife of Black Womxn’s Intervention’, in Emejulu, A. and Sobande, F. (eds) To Exist is to Resist. Pluto Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvg8p6cc.

Dery, M. (2014) ‘Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose’ (FLAME WARS: THE DISCOURSE OF CYBERCULTURE). Duke University Press. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/278667733_Black_to_the_Future_Interviews_with_Samuel_R_Delany_Greg_Tate_and_Tricia_Rose_FLAME_WARS_THE_DISCOURSE_OF_CYBERCULTURE (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Desai, O. (no date) ‘Working with people to make art: Oral history, artistic practice, and art education’, p. 10.

Diallo, O.-K. M. (no date) ‘At the Margins of Institutional Whiteness: Black Women in Danish Academia’, in Akwugo Emejulu and Francesca Sobande (eds) To Exist is to Resist. Pluto Press, p. 11. Available at: URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvg8p6cc.20 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Diggs, P. (no date) Milk Carton, PEGGY DIGGS. Available at: http://www.peggydiggs.net/milk-carton (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Emejulu, A. and Sobande, F. (2019) ‘On the Problems and Possibilities of European Black Feminism and Afrofeminism’, in Sobande, F. and Emejulu, A. (eds) To Exist is to Resist. Pluto Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvg8p6cc.4 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Eshun, K. (2003) ‘Further Considerations of Afrofuturism’, CR: The New Centennial Review, 3(2), pp. 287–302. doi: 10.1353/ncr.2003.0021.

Fife, K. et al. (no date) ‘Building a community of critical practice through reflective reading’, p. 3.

Gayle, R. (2020) ‘Creative Futures of Black (British) Feminism in Austerity and Brexit Times’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, p. tran.12381. doi: 10.1111/tran.12381.

GOULD, S. Z. (2016) ‘Challenges in exhibiting oral history’, OUPblog, 4 March. Available at: https://blog.oup.com/2016/03/exhibiting-oral-history/ (Accessed: 9 March 2020).

Gunaratnam, Y. (2014) ‘Introduction Black British Feminism’, 108(1), p. 10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.2014.36.

Guthrie, R. (no date) ‘Redefining the Colonial: An Afrofuturist Analysis of Wakanda and Speculative Fiction’, p. 14.

Hawgood, A. (2019) ‘A Student Who Makes African Emojis’, The New York Times, 11 December. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/11/style/a-student-who-makes-african-emojis.html (Accessed: 2 March 2020).

Heuchan, C. (2019) ‘A Black Feminist’s Guide to Improper Activism’, in Emejulu, A. and Sobande, F. (eds) To Exist is to Resist. Pluto Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvg8p6cc.

Howse, M. (2019) ‘Creating a Space Within the German Academy’, in Emejulu, A. and Sobande, F. (eds) To Exist is to Resist: Black Feminism in Europe. Pluto Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvg8p6cc.

Körner, J. (2019) Julia Körner, jkdesign. Available at: https://www.juliakoerner.com (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Lukate, J. M. (2019) ‘Blackness Disrupts My Germanness.’ On Embodiment and Questions of Identity and Belonging Among Women of Colour in Germany’, in Emejulu, A. and Sobande, F. (eds) To Exist is to Resist. Pluto Press, p. 14. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvg8p6cc.12 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Marine, B. (no date) ‘How Ruth Carter, Black Panther Costume Designer and Oscar Nominee, Put a “Wakandan Spin” on the Film’, W Magazine | Women’s Fashion & Celebrity News. Available at: https://www.wmagazine.com/story/ruth-carter-black-panther-costume-designer-interview/ (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Nadesan, N. (2019) ‘Black and Womxn of Colour Feminist Activism in Madrid’, in Emejulu, A. and Sobande, F. (eds) To Exist is to Resist: Black Feminism in Europe. Pluto Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvg8p6cc.

Noble, S. U. (2018a) ‘A Society, Searching’, in Algorithms of Oppression. New York: NYU Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pwt9w5.5 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Noble, S. U. (2018c) ‘Searching for People and Communities’, in Algorithms of Oppression. New York: NYU Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pwt9w5.7 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Noble, S. U. (2018d) ‘Searching for Protections from Search Engines’, in Algorithms of Oppression. New York: NYU Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pwt9w5.8 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Noble, S. U. (2018e) ‘The Future of Knowledge in the Public’, in Algorithms of Oppression. New York: NYU Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pwt9w5.9 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Obasi, C. (2019) ‘Africanist Sista-hood in Britain: Creating Our Own Pathways’, in To Exist is to Resist. Pluto Press, p. 15. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvg8p6cc.21 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Okpewho, I. (2003) ‘Oral Tradition: Do Storytellers Lie?’, Journal of Folklore Research, 40(3), p. 19.

Oral History & Technology (no date) Oral History, Oral History & Technology. Available at: https://oralhistory.eu/ (Accessed: 14 March 2020).

Oral History Archives of Japanese Art (no date) Oral History Archives of Japanese Art, Oral History Archives of Japanese Art. Available at: http://www.oralarthistory.org/index_en.php (Accessed: 10 March 2020).

Othieno, C. A. and Davis, A. (no date) Those Who Fight For Us Without Us Are Against Us: Afrofeminist Activism in France. Edited by A. Emejulu and F. Sobande. Pluto Press. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvg8p6cc.7 (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Porter, B. (no date) The Art of Digital Storytelling, Creative Educator. Available at: https://creativeeducator.tech4learning.com/v04/articles/The_Art_of_Digital_Storytelling (Accessed: 9 March 2020).

Postill, J. and Pink, S. (2012) ‘Social Media Ethnography: The Digital Researcher in a Messy Web’, Media International Australia, 145(1), pp. 123–134. doi: 10.1177/1329878X1214500114.

Qureshi, S. (2019) ‘A Manifesto for Survival’, in Emejulu, A. and Sobande, F. (eds) To Exist is to Resist: Black Feminism in Europe. Pluto Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvg8p6cc.

Reef, A. (2008) ‘African Words, Academic Choices: Re-Presenting Interviews and Oral Histories’, History in Africa, 35, pp. 419–438. doi: 10.1353/hia.0.0002.

Ryzik, M. (2018) ‘The Afrofuturistic Designs of “Black Panther”’, The New York Times, 23 February. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/23/movies/black-panther-afrofuturism-costumes-ruth-carter.html (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Sackey, E. (1991) ‘Oral Tradition and the African Novel’, MFS Modern Fiction Studies, 37(3), pp. 389–407. doi: 10.1353/mfs.0.0987.

Siddiqui, S. (2018) ‘Still The Heart of the Race, thirty years on | Institute of Race Relations’, Institute of Race Relations. Available at: http://www.irr.org.uk/news/still-the-heart-of-the-race-thirty-years-on/ (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Sobande, F., Fearfull, A. and Brownlie, D. (2019) ‘Resisting media marginalisation: Black women’s digital content and collectivity’, Consumption Markets & Culture, pp. 1–16. doi: 10.1080/10253866.2019.1571491.

Stanhope, S. (2019) ‘Feminist Blogger And Best-Selling Writer Causes Outrage By Saying “If men are committing s*icide as they can’t cry, how’s it my concern?”’, Eighties Kids, 13 March. Available at: https://www.eightieskids.com/slumflower (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Stone, K. F. (1981) ‘The Uses and Abuses of Traditional Oral Tales’, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 6(2), pp. 13–14. doi: 10.1353/chq.0.1545.

Syms, M. (no date) S7 E1: The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otUJvQhCjJ0 (Accessed: 2 March 2020).

Tate (no date a) Afrofuturism – Art Term, Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/a/afrofuturism (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Tate (no date b) The Other Story and the Past Imperfect – Tate Papers, Tate. Available at: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/no-12/the-other-story-and-the-past-imperfect (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

Thrasher, S. W. (2015) ‘Afrofuturism: reimagining science and the future from a black perspective’, The Guardian, 7 December. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2015/dec/07/afrofuturism-black-identity-future-science-technology (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Tshidzu, B. (no date) ‘MA in Computational Arts blog › CULTURAL ARCHIVING THROUGH COMPUTATIONAL GENERATIVE AFRICAN PRINT TAPESTRY.’, MA in Computational Arts blog. Available at: http://doc.gold.ac.uk/compartsblog/index.php/work/cultural-archiving-through-computational-generative-african-print-tapestry/ (Accessed: 2 March 2020).

Tuwe, K. (2015) ‘The African Oral Tradition Paradigm of Storytelling as a Methodological Framework: Employment Experiences for African communities in New Zealand’, African Studies Association of Australasia and the Pacific (AFSAAP)., p. 18.

Ugwu, R. (2020) ‘The Hashtag That Changed the Oscars: An Oral History’, The New York Times, 6 February. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/06/movies/oscarssowhite-history.html (Accessed: 19 April 2020).

van Veen, tobias c. (2013) ‘Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture’, Dancecult, 5(2), pp. 152–157. doi: 10.12801/1947-5403.2013.05.02.08.

wikipedia (2020) ‘Tomie Arai’, Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Tomie_Arai&oldid=943951316 (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Womack, Y. (no date) ytashawomack.com, ytashawomack.com. Available at: https://www.ytashawomack.com (Accessed: 12 March 2020).

Zaphiriou-Zarifi, V. (2019) ‘The Collective Mobilisation of African Women in Athens “United We Stand”’, in Akwugo Emejulu and Francesca Sobande (eds) To Exist is to Resist. Pluto Press. Available at: The Collective Mobilisation of African Women in Athens ‘United We Stand’ (Accessed: 19 April 2020).