Aliceomenology

Algorithms and Mental health on Instagram

Humans are inherently socialbeings and ever since our hunter gatherer ancestors, we have been always oriented towards others, looking for ways to connect and be part of a clan, tribe or a network. Humans are not unique creatures with these attributes, but it is the complex nature of our compass for connection, collaboration, and participation that make us singular and belong to a distinguished behavioural modernity (Petraglia and Korisettar, 2012).

With the advent of the printing press in the fifteenth century, knowledge, for the first time, has been accessible more than ever, and mass communication has been revolutionized. Fast forward to the present, passing histories of other communicative technologies such as the telephone and television, the advent phenomena of the internet has oriented us to the pinnacle of evolution connectiveness, that of the human communication sphere, which lie along online platforms of social networks as we know them today.

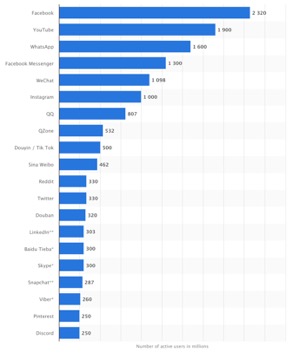

Social networks which is part of social media (Dines, 2011), are platforms for communication between people using computer mediated technologies. Communication is user-generated in the form of sharing news, ideas, thoughts, pictures, or any kind of information imaginable. Due to the fact that social media started after the inception of the internet, it is fair to say that its history is quite short, in fact, most of us witnessed its birth. The first ever social media platform was launched in 1997under the name of “Six Degrees”, it only lasted a few years before it was shut down. Since then, other platforms emerged, some disappeared, others are still going on in full force with millions of active users.

From the big five social media platforms that exist today: Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Snapchat and Instagram, Instagram- a social photo sharing app- is the most visual, visible and accessible apps of them all, there are no hidden manoeuvres or secret finger haptic movements as in snapchat, and it only exist on mobile held devices and tablets. A picture is worth a thousand words,as the saying goes, and it is exactly that. It is seductive to a younger generation of the millennials, generation z, and the iGens (Twenge, 2018).

Instagram was launched in 2010 by Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger, and then in 2012, was sold to Facebook for a billion dollars. Based on Statista anonline market research portal that provides statistics and data about industries for industries, to date, Instagram has over a billion active users worldwide (Statista, 2019).

Instagram separated itself from other social media competitors by only focusing primarily on shared photos and videos that give it the advantageous condition in gaining popularity and prevalenceespecially with the younger generation who prefer communication through visual means. According to The Pew Research, Centre for nonpartisan American fact tank in Washington,around one-third of online adults (32%) report using Instagram, Roughly six-in-ten online adults ages 18-29 (59%) use Instagram, nearly double the share among 30- to 49-year-olds (33%) and more than seven times the share among those 65 and older (8%) ( Greenwood et al., 2016).

As the popularity with Instagram grows among a younger generation, some studies showthat excessive Instagram usage have been contributing to mental disorders and has been associated with addiction, depression, anxiety, loneliness and low self-esteem (Kircaburun, Griffiths,2018) (Ershad, Z., Aghajani,2017) . Furthermore, with the ongoing gratifications Instagram employs with “likes”, positive commentary, and notifications, individuals get dependant on these rewards that they are experiencing online and that which they are not being recognised for offline, and with this constant repeated need for gratification and recognition, it becomes problematic (Ryan et al, 2014).My first introduction to Instagram was in 2012, when I downloaded the app and encouraged by a friend, I posted my first picture. Since then, I have been gradually using it extensively and it has been my primary social networking outlet. Throughout the years, I have witnessed a lot of changes on Instagram, from algorithms that display reverse-chronological feed, to the current algorithms that priorities accounts that the user had the most engagement with. From 15 video clips to one-minute multiple ones. From simple editing filters to cloning snap-chat features and implementations. The more Instagram introduced new elements, the more time I found myself on the app. With “ Screen Time”, a new feature on my mobile phone that helps the user monitor the amount of minutes and hours spent on different apps and platforms, my Instagram habits became more pronounced: not only did I have a behavioural problem associated with Instagram, but I was becoming more self-critical and self-conscious. These varying affects from using Instagram, prompted me to my Computational arts research speculative proposal: “Algorithmic behaviour and mental health on Instagram”.

Part of the business model Instagram is using is a model to extract human attention and exploit their mind’s vulnerabilities, and the algorithms that are employed use recommendations generated by these algorithms to keep users clicking (Harris, 2016). Psychological hooks are created to build addictive user habits by forming external and internal triggers that when instigated, they are tied to an immediate reward,particularly when we feel “bored, lonely, confused, fearful, lost or indecisive.” (Eyal, 2017).

Jaron Lanier, who is considered the founding father of VR, has raised his concerns about the influence of social media. His criticisms are that such platforms have made us “cruder, less empathetic, and more tribal”. He continuous to talk about how we are manipulated by algorithms that constantly watch us and that this constant online surveillance on these platforms is modifying our behaviours all the time, reducing our capacity to think for ourselves, and making us depressed and stressed (Lanier,2018).

The algorithm that Instagram initially deployed since its inception was a simple one based on the order of the user’s posts in a reverse chronological manner. In April 2016,Instagram began rolling out a change to this order of photos on the user’s timeline, shifting to one that relieson machine learning based on the user’s past behaviour to create a unique feed for everyone (Constine, 2018). There are three main factors the new algorithm takes in consideration: The probability of a user’s interest in a post based on previous engagements, the date of the post when it was published, and the relationship between the user and the post creator based on their engagement previously together, where this engagement circulated around common interactions between them in the form of commenting, liking and tagging. Furthermore, the algorithm has an image-recognition tool factored to be part of it, which will determine specific objects within an image. This will organize content into topics and channels that will cater to the user’s past interest. In other words, if a user likes an image of a dog, more dog images will appear in the user’s explorer page. This will carry weight with marketers to significantly shift their advertisement strategies towards their target audiences, especially that the new algorithm has succeeded in more user attention; from twenty-one minutes before the new changes, to twenty-four minutes following the changes (Hutchinson, 2018).

As the new Instagram algorithm controls the order of the posts that users see when they’re scrolling through their feed, the questions is, how will the Instagram Algorithm reflect on users with mental health issues. Moreover, by pushing the most relevant posts to be most visible and prioritizing them based on previous user interaction, how will that affect users with mental disorders who keep clicking on posts with negative emotional messages. It is not just about liking cute images of dogs or sandy beaches anymore. These are some of the speculative questions that I am investigating with the project I carried out for this research paper. I want to show how the Instagram algorithm works against the wellbeing of users with mental health issues and unravel the dangerous implication that might arise from having an algorithm that curates a user’s feed. To explore these questions, an Instagram account was created under the name of “Alice”, a character that was invented for the purpose of this report. Alice is what I consider, an Alien Phenomenology (Bogost, 2012). Alice is an object, an androgynous thing, a protagonist agent in its lonely online presence. Of course, this experience of what a thing is takes from human perception through a speculative philosophy based on metaphors (Bogost, 2012). Alice has an affordance of perceived humanistic properties. Let me start my defining what the term affordance refers to with reference to Alice. Affordance is how an object should be utilised by providing itself or its context,therefore, it is something of both actual and perceived properties. And when these two properties are combined, an affordance develops as an association that holds between the object and the person that is acting on it. "...the term affordance refers to the perceived and actual properties of the thing, primarily those fundamental properties that determine just how the thing could possibly be used. [...] Affordances provide strong clues to the operations of things. Plates are for pushing. Knobs are for turning. Slots are for inserting things into. Balls are for throwing or bouncing. When affordances are taken advantage of, the user knows what to do just by looking: no picture, label, or instruction needed." (Norman, 1988, p 9). Alice will be portrayed as a character with an undiagnosed mental illness. Alice is prone to thoughts of depression, self-abhorrence, and suicidal thoughts. Alice displays functions of unsatisfactory levels of behavioural adjustment and does not show signs of phycological resilience (Lopez et al. 2014). Using digital ethnography to report on the Alice phenomena, I will observe how other accounts will engage with posts I upload as Alice, examine Alice’s interactions with accounts Alice follows, and check how the IG (Instagram) algorithm will organise the feeds based on these interactions and engagements.

Alice’s IG account was created on the 2ndof April and for the first post, I made the decision to use an app that boost followers and likes to give the account more exposure. Therefore, I will not include the interaction of the first picture with my analysis.

As hashtags are important in circulating posts on IG, I have used the following hashtags in various degrees across the posts that were made:

#lonely #journey #nolove #alone #die #life #mylove #tolove #lovers #bored #boring #boringday #unhappy #broken #sadquotes #brokenhearted #heartbreak #photooftheday #hurt #thoughts #darkness #anxiety #depressed #mood #badmood #sad #sadness #upset #stressed #hate #tears #crying #lifesucks #instaSad #annoyed #cheermeup #crappyMood #help #crappyDay #crying #lifeSucks #empty #tears #guilty #ugly #blue #death #aliceomenology

Furthermore, with each post, Alice used a quote or a comment that stipulated that there were symptoms of an unstable mental state. Some of the comments were:

Dreading facing another day.

A long boring day.

Not very hungry.

No matter how much you try to get up, nothing is moving, you are stuck.

I feel too ugly to speak to anyone.

It’s that sort of day.

I am full but feel empty.

Why do I always feel guilty? So Lonely. Just lie down.

Silence.

What is the purpose of life?

Another boring Sunday.

Life and Death.

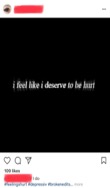

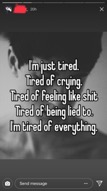

In addition, Alice started to follow other accounts that had the same inclination and interests. Alice found these accounts from the explorer page the algorithm was feeding. There were plenty, and Alice ended up following 44 different accounts. Some of the accounts were disturbing to look at, and as I/Alice had to interact with them, I found the action of clicking “like” emotionally difficult , but it was important to continue clicking to watch these users stories, I wanted to engage more with such accounts to investigate the Algorithm that IG was applying. Some of the stories varied between suicidal messages, cries for intervention, and self-hurt images of users. These messages were mostly found in the stories of public Instagram accounts.

Warning: The following 2 pages include sensitive content.(In PDF)

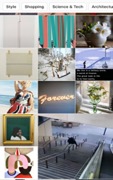

Furthermore, as this speculative research was about how the IG algorithm performs with users, in particular with users with mental health issues, I had a snap shot of the discovery page before any posts Alice made. The DP was very generic, there were random posts that ranged from public profiles to art and design.

Meanwhile, the DP have changed slowly during Alice’s 34 days of posting. The algorithm started to curate pages that related to what Alice was liking and viewing. There was a noticeable sway towards other accounts that displayed mental health concerns.

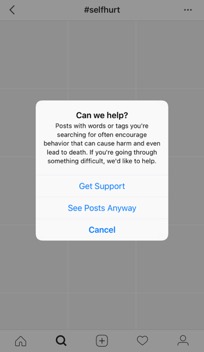

The experiment lasted only for 34 days with only 24 posts. Although it was a short period to conduct such an experiment, it didserve my speculational concerns related to the Algorithm that Instagram diploys, which is that the Instagram Algorithm does not work for the benefit of users with mental health problems. Saying that, when Alice used the search option for #selfHarm, Instagram posted a message to offer support, but then, this message is automated with any key words that Instagram flags as allarming or unsettleing, and had nothing to do with the algorithm that controles the content that was chosen for the user based on the users previous choices.

In June 2018, Instagram had a press briefing where they explained how the Instagram Algorithms worked. It prioritizes content from other accounts that users interact with such as leaving comments, direct messages or tagging. The algorithm identifies that these users are close. Moreover, the algorithm predicts which posts are important to users based on their past behaviour, hence the user will most likely see similar contents to the ones that were engaged with. With users that have undiagnosed mental health issued, and who identify with similar accounts as theirs, this will reinforce their illness by having the algorithm persisting on categorizing them within related clusters, which could spiral them into more sever emotional complications. Consequently, if a user has self-hate issues, these feelings will be reinforced by the algorithm by classifying that user with similar users of self-hate. This is a problem Instagram has to address. This is not about the affects of what Instagram can have on users with a healthy mental well-being such as addiction and gratification, rather, it is about users with dispositions of mental health problems that are inclined to be more sensitive than the rest. The whole aim of Instagram is to enhance social connectivity, yet that is not the case with users with mental health problems who need, guidance, help and human intervention, in particular vulnerable teenagers and young adults.

My examination of the algorithm was done individually, and in a short period of time. Further research must be done to investigate this with a larger scale of user participation. In conclusion, this report has shown that there are some faults with the algorithm that Instagram employs, and with more than a billion users who are active on this platform, more action is required from Instagram to improve their algorithm.

Alice’s journey ends with this report, but their digital footprint still continues at https://www.instagram.com/aliceomenology/

Note: The report was written with Images that support it through out the paper as a PDF file. This could not be done here. I had to cluster the Images in one group, which might make reading the report on this platform unclear at times without supporting images underling the paragraphs. Furthermore, due to sensitive material,Some of the images were not included in this blog.

References

Allen, K., Ryan, T., Gray, D., McInerney, D. and Waters, L. (2014). Social Media Use and Social Connectedness in Adolescents: The Positives and the Potential Pitfalls. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 31(1), pp.18-31.

Center For Humane Technology. (2019). Center for Humane Technology: Realigning Technology with Humanity. [online] Available at: https://humanetech.com [Accessed 10 May 2019].

Constine, J. (2018). 'How Instagram Algorithm Work. TechCrunch. [online] Available at: https://tcrn.ch/2LN5kDX [Accessed 11 May 2019].

Dines, G. and Humez, J. (2011). Gender, race, and class in media. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

Ershad, Z. and Aghajani, T. (2019). Prediction of Instagram Social Network Addiction Based on the Personality, Alexithymia and Attachment Styles. [online] Ssyj.baboliau.ac.ir. Available at: http://ssyj.baboliau.ac.ir/article_533425.html [Accessed 13 May 2019].

Eyal, N. and Hoover, R. (2014). Hooked. Portfolio Penguin.

GREENWOOD, S., PERRIN, A. and DUGGAN, M. (2019). Demographics of Social Media Users in 2016. [online] Pew Research Centre: Internet, Science & Tech. Available at: https://www.pewinternet.org/2016/11/11/social-media-update-2016/ [Accessed 9 May 2019].

Harris, Tristan. Centre For Humane Technology. (2019). Centre for Humane Technology: Realigning Technology with Humanity. [online] Available at: https://humanetech.com [Accessed 10 May 2019].

Hawi, N. and Samaha, M. (2016). The Relations Among Social Media Addiction, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction in University Students. Social Science Computer Review, 35(5), pp.576-586.

Hutchinson, A. (2018). Instagram Explains How Its Algorithm Works in New Briefing. Social Media Today. [online] Available at: https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/instagram-explains-how-its-algorithm-works-in-new-briefing/524825/ [Accessed 11 May 2019].

Kircaburun, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Instagram addiction and the Big Five of personality: The mediating role of self-liking. Journal of behavioural addictions, 7(1), 158–170. doi:10.1556/2006.7.2018.15

Lanier, J. (2018). Ten arguments for deleting your social media accounts right now. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Lopez, S., Pedrotti, J. and Snyder, C. (2014). Positive psychology. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Norman, D. (1988). The psychology of everyday things. New York: Basic Books.

Petraglia, M. and Korisettar, R. (2012). Early human behaviour in global context. London: Routledge.

Statista. (2019). Global social media ranking 2019 | Statistic. [online] Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ [Accessed 9 May 2019].

Twenge PhD, J. (2018). iGen: Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy--and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood--and What That Means for the Rest of Us. 1st ed. Atria Books.

Bibliography

Conole, G., 2013. Designing for learning in an open world, New York: Springer.

Lovink, G. (2016). Social media abyss. 1st ed. Polity.

Sampson, T., Maddison, S. & Ellis, D., 2018. Affect and social media. Emotion, mediation, anxiety and contagion, Blue Ridge Summit: Rowman & Littlefield Publ.

Turkle, S., 2017.Alone together: why we expect more from technology and less from each other. New York: Basic Books.