Rose Tint my Glasses, Felling Our Space

Enmeshed: What sort of aesthetic emerges in-between mediatization, performance and dance? Exploring the nature of mass media, and visual and performance art, this paper explores dance and performance by a new generation of companies who have extended their practices to include mediatization in conversation with the world which surrounds them. What does mediatization, the digital and computation do to the aesthetics of dance and performance and who has access and how to computational technologies. A brief and partial tracing of the lineage of mediatization and computation as it relates to dance and performance practices in the western world and specifically in the United States, Europe and England starting from the early 1950s and running through to the 2010s is outlined. Following this a fieldwork study was conducted for this paper. I led a workshop specifically created for dancers to use virtual reality in the dance studio context based on my professional experience as a choreographer, dance maker and creative coder. Interviews and feedback throughout the workshop were recorded collecting the testimonies of the dancers. The findings from the field study are what follows.

produced by: Jana Velinova

Project Report

Introduction

To start with, what follows is a brief and partial tracing of the lineage of mediatization and computation as it relates to dance and performance practices in the western world and specifically in the United States, Europe and England starting from the early 1950s and running through to the 2010s. I would like to here define mediatized as being anything that is recorded, broadcast or, anything that is part of technological media. Mediatization historically in relation to performance starts in the early 20th century with radio and music recordings beginning in 1934, and eventually developing into TV, video, film, podcast, social media and so on.

In her monumental 1993 book Unmarked, performance theorist Peggy Phelan famously claimed the ephemerality of dance. Describing dance as that which appears only by its disappearance. For Phelan, media would and should have been perhaps, only a documentation of a live event or performance. Media not being the live performance event itself but a mediatization of it, only a recording.

Thinking through a computational-arts perspective however, we can start to consider media as that which is culture. Because media surrounds us in many parts of the world today. We are constantly seeing 2D images, hearing music and logging on to social media regardless of our place, age, or any other personal identifier. Just looking around, if you are in any city - New York, London, San Francisco, Barcelona, Prague, Belgrade, Copenhagen, Marrakesh - taking any form of public transportation, it isn’t hard to see that Marshall McLuhan seems to have been right. Everyone is moving through the world and society while enveloped in their own reality in their own headphones, screens and devices creating their own personal mediatized escape.

As Peter Wright and John McCarthy have said “much more deeply than ever before, we are aware that interacting with technology involves us emotionally, intellectually and sensually” and “we don’t just use technology; we live with it.” (p.iv) This frame of thinking about technology as something we live with, has an effect on live performance, dance and culture at large.

What is a live performance right now anyway?

At a pop music concert, for example, you are at a live performance with the performer there present but the music is prerecorded. Often these shows have visual backdrops and screens with videos and projection, all recorded in advance and used for performance effect and yet we still think of those events as live events. The dissemination of the recorded event is so widespread, pop singers often also have a lot of pressure to recreate the conditions of the recorded performance, and reproduce the music video live exactly as it was in the video. The audience would be disappointed if their live performance didn’t look like the music videos or sound like the recording. When this doesn’t work we have some funny examples of pop starts lip syncing. Famously Milly Vanilly, Ashley Simpson, Lady Gaga, Mariah Carey, Beyoncé, and many more have been caught in awkward situations when they were supposed to be performing live and were actually using a recording of themselves singing. According to Philip Auslander, the pressure of having to recreate both the recorded sound and the music video has pushed these performers into starting to use recorded images and sound in their live performance. So the live performance starts to emulate and look more and more like the recorded one because it has recorded elements folded into it. Creating an aesthetic effect very different from using the recording as simple documentation.

So what makes these performances live? Auslander says: “our experience of liveness and our understanding of what counts as a live performance change continually over time in response to the development of new media technologies” (Cambridge, 109) For Auslander, the only reason we can make the distinction about what is live is that we have the recorded. We only see live because we know there is something else that’s different from it. He explains the relationship between the live and mediatized is more difficult than just making a binary distinction between this was recorded and that was live. He is concerned with what the experience of the live event is that we receive via the media. So to him, there is a new term that emerges and that is “live-ness.” Auslander’s live-ness is different than live. Live-ness is built primarily around the audience’s affective experience. “To the extent that Websites and other virtual entities respond to us in real time, they feel live to us and this may be the kind of liveness we now value.” (Cambridge, 112)

In other words, live-ness has to do with the digital and results from our engagement with it.

The use of this method choreographically has an effect on the works interactivity. When the performers' employee liveness be that as the use of recorded media in performance, the dissemination of live work via the internet and so on they create a new kind of interactivity between the spectator and the performer that involves the digital.

This new kind of interactivity can be described as a live that is in time, it is now. Perhaps not in the same place but it is in the same time. If I share a moment of now with someone else than we are live together. If I share a moment of now with a performer then we are live together. An everyday example of this might be Google Hangouts. On a cell phone in my pocket, I carry all the people I care about right there in my pocket. If I want to share a moment now with any of them I just use my phone and text. I interact with the digital device and have a real-time connection. I am live with a person in a totally different place, right now. They are not here, we are not sharing the same space but they are now we are sharing the same time and the instant ping of my phone lets me know they are with me now. Other examples of this sort of interaction with the digital can be: social media, video games, working on a computer, and so on.

What is it about mediatized forms that makes them so appealing to so many people? Use of the internet for example to shop is done by a great percentage of people in the developed world, ranging from the latest electronic, toy or book on Amazon to a used sofa on Craig’s List or Gumtree. So why do people find particular shopping experiences appealing or pleasurable? In part, I think because everybody wants to be moved. In an age of digitalization, everyone says “move me.” The story that those websites or products tell, the mood they set, the personal connection affecting the buyer help to seal the deal. “For example, companies like Nike have begun to design cinematic, highly interactive retail sites that evoke emotion and invite customers to identify with their product and company culture.” (Wright and McCarthy, 2003).

Aesthetics

This interactivity and mediatization generally affect the aesthetics of art and performance as well in many ways. Some effects I have personally found effective while incorporating computation into my own shows are misrecognition, the creation of confusion, and creation of a series of intensities, a layering of the performance elements, and a changing of time or confusion of realms.

There are a number of performers that have historically worked at the crossroads of dance, movement, media, computing and other technologies. We can trace back to artists of the likes of Ian Breakwell.

“Breakwell, one of a group of radical British artists who, in the 60s, challenged the conventional orthodoxy of modernism, the results of this challenging were the ‘dematerialization’ of the art object from its traditional, commercially marketable format as painting or sculpture to its reconstitution as text, document, photograph or other cheap, reproducible or even insubstantial material. The modernist notion of expressive creativity was rejected and strategies of detachment were adopted. Many artists of this generation used the techniques of the social scientist, documenting their lives or the lives of those around them using photography, recorded notes and journals.” (E.Manchester, Tate)

A foreshadowing perhaps of the soon to come internet concept of blogging or recording one’s doings for publication.

Of course here one could not forget Stelarc and his premise of the human body as obsolete making his performances centered on his physical self as canvas via flesh manipulation from the late 1970’s through to today.

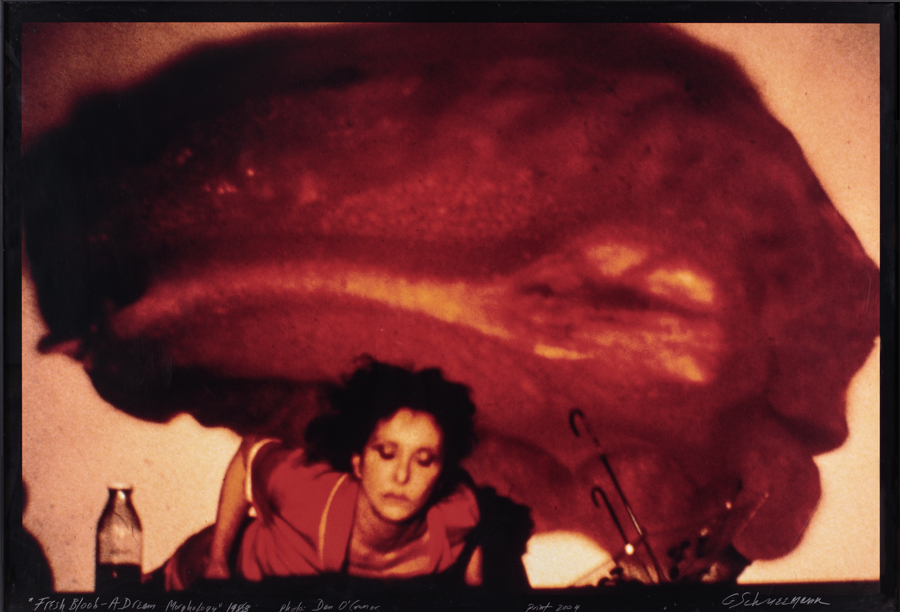

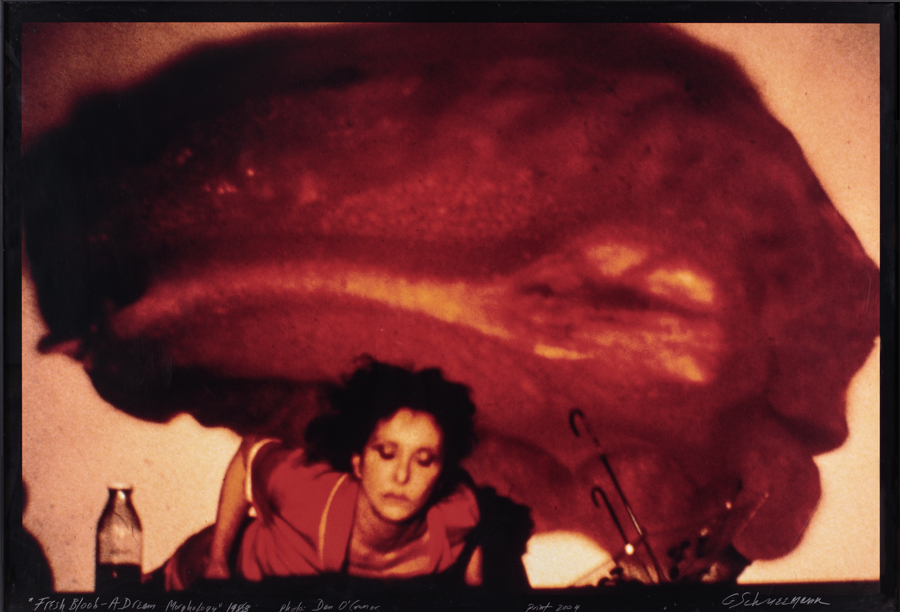

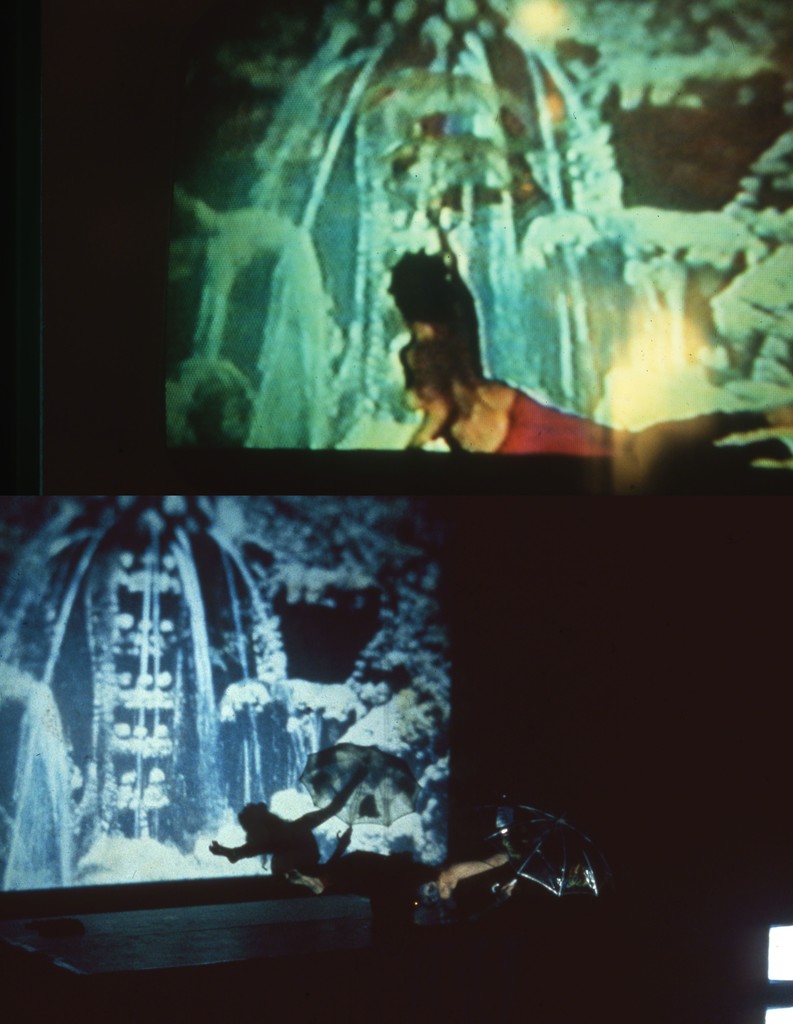

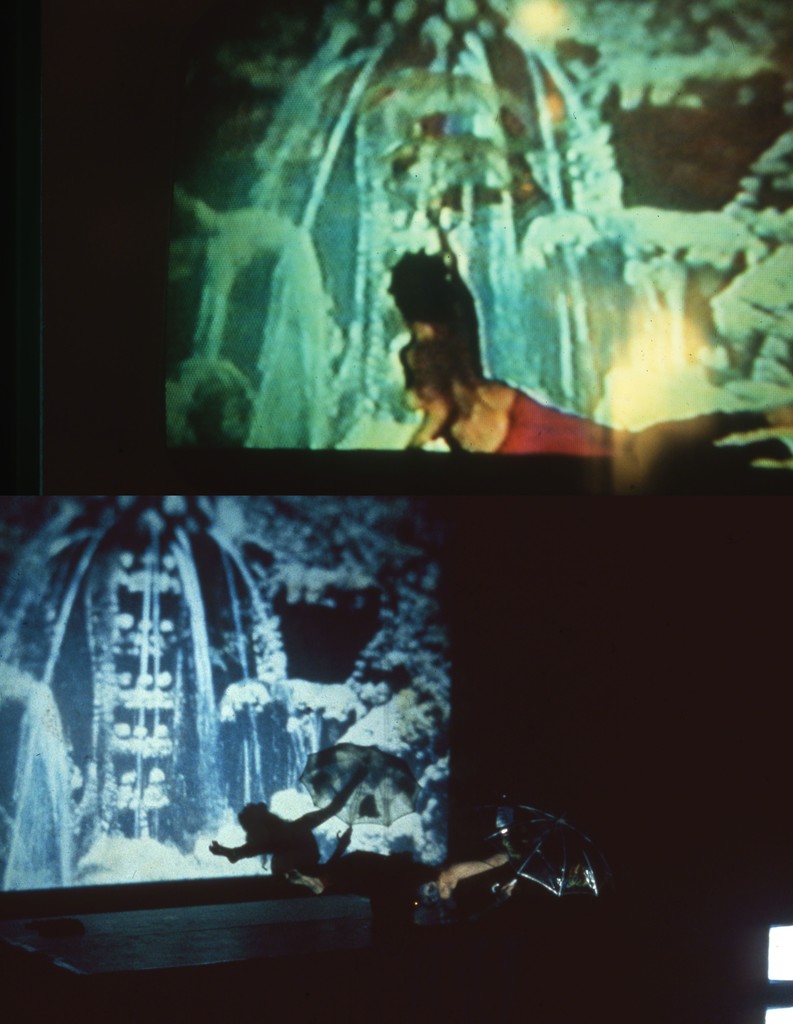

Then too, before even the establishment of object-oriented ontology was Carolee Schneemann who created "Meat Joy" (1964) and began to make a spectacle of the body. Starting to think about the body as a material rather than thinking of its humanity. Just like a chicken is a material or a plastic on a cellphone is one so too is a human body. Schneemann’s early performance was a mixed media of dead chickens, blood, naked bodies, fluids and ritual. She used sound in a very visual way turning it into the dance itself and then into the choreography as she experimented with choreographic thinking as it relates to sound and vibration rather than to human bodies. Her later work perhaps more apparently is connected to computation, creating pieces like “Fresh Blood” (1981) which was a dream originating work of “V” shapes created by Schneemann and composed together to form a visual dictionary of in a series of varying media including projection, installations, film and video over the course of ten years.

Around the same time in 1966 the EAT nights - 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering – were held in New Jersey, USA. Artist John Cage, Lucinda Childs, Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Robert Rauschenberg, David Tudor, and Robert Whitman where among those that participated in a sharing between artists and notable engineers Fred Waldhauer, Manfred Schroeder, John Pierce, Max Mathews, Billy Kluver and Bela Julesz to work together for 10 months developing technical equipment and systems that were then used as an integral part of the artists’ performances.

Merce Cunningham and John Cage too incorporated mediatization early on. Beginning perhaps with their unconventional dance performances in gymnasiums as well as in site-specific spaces. The choreography Summerspace is a dance that has no center and is seen from all angles having a 360-degree view. Cunningham and Cage, therefore made immersive performance in 1963 long before immersive videos also know as 360-degree videos were ever invented in 2013. The dance duo famously also pioneered the use of the software they named “LifeForms” into their choreographic practice in the 1980’s where a computer generated movement beyond what was possible physically or imaginatively for a person helped shape their work.

The software “Isadora” a graphic programming environment was developed by Troika Ranch dance and by Mark Coniglio in 2002 with an emphasis on real-time manipulation of digital video for live performance.

Even more recently, since 2006 Johannes Berringer has been dedicated to the investigations of wearable technology in cross-over fields of performance, music, design, digital art and fashion. As a choreographer himself Berringer co-created the "DAP-Lab", together with Michèle Danjoux.

In developing wearable prototypes for performance in networked dance environments and fashion contexts Berringer is in a way creating a different body. The possibilities of what the physical body can do on stage open and become wider with wearable prototypes and technology for performance. “Wearable computing devices worn on the body provide the potential for digital interaction in the world. A new stage of computing technology at the beginning of the 21st Century links the personal and the pervasive through mobile wearables” – Berringer (Wearable performance)

In 2012, Janet Cardiff and George Miller began performing “Walks” which use a cellphone as a way to displace the audience and the performer bringing two different places together at the same time in one performance.

If we see through media as is the case for most who take public transport, for example, that would mean that the mediatized is our live experience of that event. Auslander’s thought on liveness is around re-enactments or re-productions of performance (something that has become more and more popular in the contemporary dance scene and has been a part of the ballet & theater world for a long time. Which can be controversial because some scholars have said that taking a dance out of its context means it is something completely different and can never be an exact replica of the original.) Auslander’s writings point us to the idea that: “we could only re-produce performances because we have the experience of the document.”

Virtual Reality and Dance Workshop

What place can dance find in relation to a range of different contexts in the digital? Social media, re-viewing, re-staging, quotes of other artists in live performance and distribution are just some of the ways art generally is affected by computation contemporarily.

Starting with this premise of keeping the feeling of the same time but not the same place, I held a workshop for dancers in March 2018 in London using Virtual Reality.

The primary concern I began with for this fieldwork study and the reason behind my choice of VR over any other form of mediatization was: If dance is the physicalization of conceptualization does VR increase the ease of conceptualization for dancers and therefore for composition? Can the use of VR remove some of the barriers of imagination and/or physical possibility for the dancers?

The first consideration for me in organizing the workshop event was which hardware to provide for the participants. Alongside my interest in the aesthetic, I am also concerned with access. Because Virtual Reality is objectively too expensive for most people as reported recently by business insider UK, I aimed to see if there is an accessible way for dancers in varying institutions or research and performance settings to make use of VR while overcoming its cost barrier. The solution for which I found by starting this project with using cardboard VR.

Surprisingly enough to me, the use of the cardboard VR was much more effective than anticipated. The portability and wireless-ness of the headsets actually helped in facilitating the dancers.

To structure the workshop, I used my own choreographic methodology that I have built by drawing on methods using in Skinner Release technique, Feldenkrais, and Contact Improvisation. All of these methodologies have an attention on imagination and follow a somatic approach, a great deal of what I myself am concerned with as a dancer and choreographer in creating work.

The format I planned and created was a process where 1. I would lead the dancers through an improvisation, then 2. provide them with an introduction to a VR environment while they are at physical rest and then 3. Take the headsets off and follow with a second led improvisation experience, 4. Talk and ask questions to see if they reported any difference in the two dancing experiences.

The software I used was the simplest downloadable google cardboard VR application free on most smartphones. This is because a) access was free and convenient for a first time VR experience for the dancers and b) that specific application is designed to take the user to a variety of different places real and imagined fitting in with the original premise of all the dancers and I keeping the same time together but feeling of being in different places.

Despite this being a single day workshop the response from the dancers was very powerful.

The format did not exactly hold either because I wanted to separate the experiences into different events. The dancers however just kept dancing the whole time. The moment they put the headsets on they just kept dancing and exploring. Seeing that there was a shift needed in my approach I decided to ask for reflections while the experience was going on. In the end, the process looked like 1. Lead improvisation based on a specific concept I set forth 2. VR headsets, all dancers moving with the headsets on with the same concept in mind 3. Everyone speaking out loud their reflections while dancing and with the headset on responding to my specific prompts and inquiries.

Some of their key reflections included:

1. “Even though most things are actually not (physically) possible because I’m not actually there, many things felt a lot more possible than in real life. I felt like I could go up and touch things that ordinarily would be way out of my reach. The worlds feel like they exist only for my private curiosity.” ~workshop participant

2. “For the duration of this workshop I have felt completely disconnected from my own world and introduced to many new ones that allow for absolute and utter feelings of freedom to explore. This experience has allowed me to reevaluate the idea of approaching sensation through my movement.” ~workshop participant

At this stage, I have understood that this was only a first step into the task of incorporating mediatization into my own artistic practice. Next steps for me will be to delve deeper into this research rereading through all interviews and documentation I have of the workshop and beginning to think about what sort of application might I start to work on developing that will even more directly help facilitate dancers and choreographers in their artistic directions.

Keywords:

Dance, Performance, Mediatization, Liveness, Interactivity, Simulation, Virtual Reality, Imagination

References:

Text

1. Auslander, P. (2008). Live and technologically mediated performance. 107-119 The Cambridge Companion to Performance Studies, Cambridge University Press, 2008

2. Auslander, Liveness Performance in mediatized culture, The MIT Press , Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England, 2008

3. John McCarthy and Peter Wright, Technology as Experience, The MIT Press , Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England, 2004

4. Peggy Peahlan, Unmarked, Physcology Press, London England, 1993

Web Resource

5. Retail website: (http://www.nike.com)

6. http://londondance.com/articles/features/merce-cunningham-and-lifeforms/

7. http://www.cardiffmiller.com/artworks/walks/index.html

8. http://uk.businessinsider.com/why-is-virtual-reality-so-expensive-2016-9

9. https://www.forbes.com/sites/robertadams/2016/10/17/5-ways-virtual-reality-will-change-the-world/#5e30160c2b01

Mediatized Dance Sources: