Boberg 1.

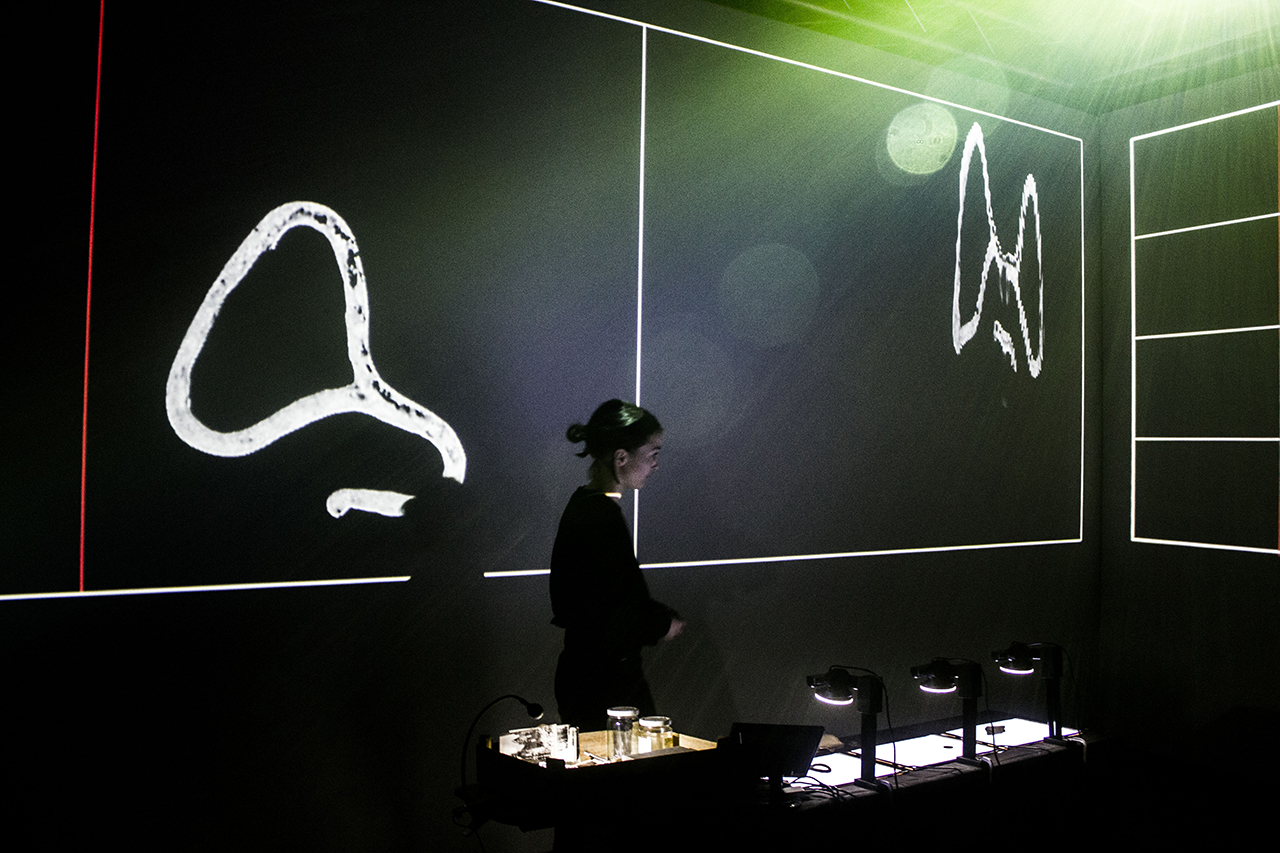

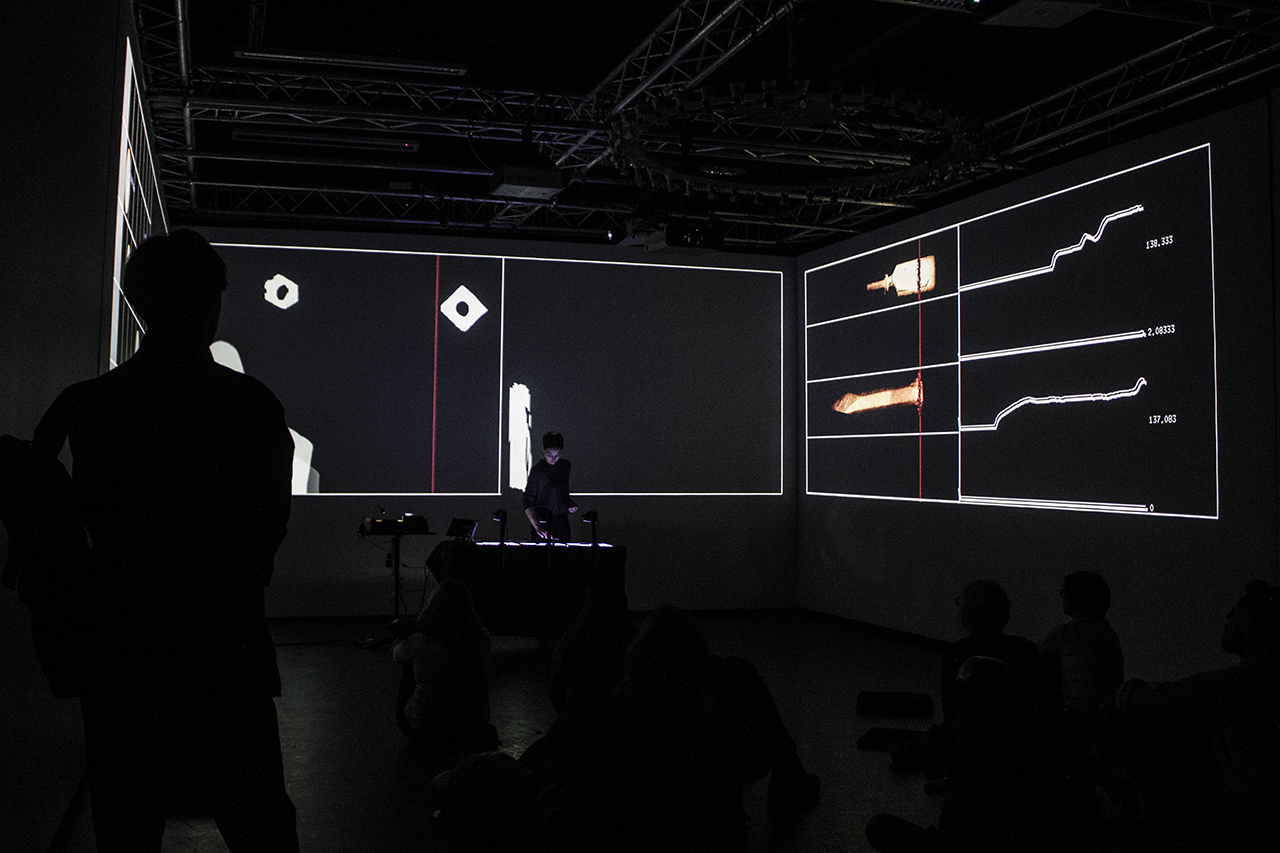

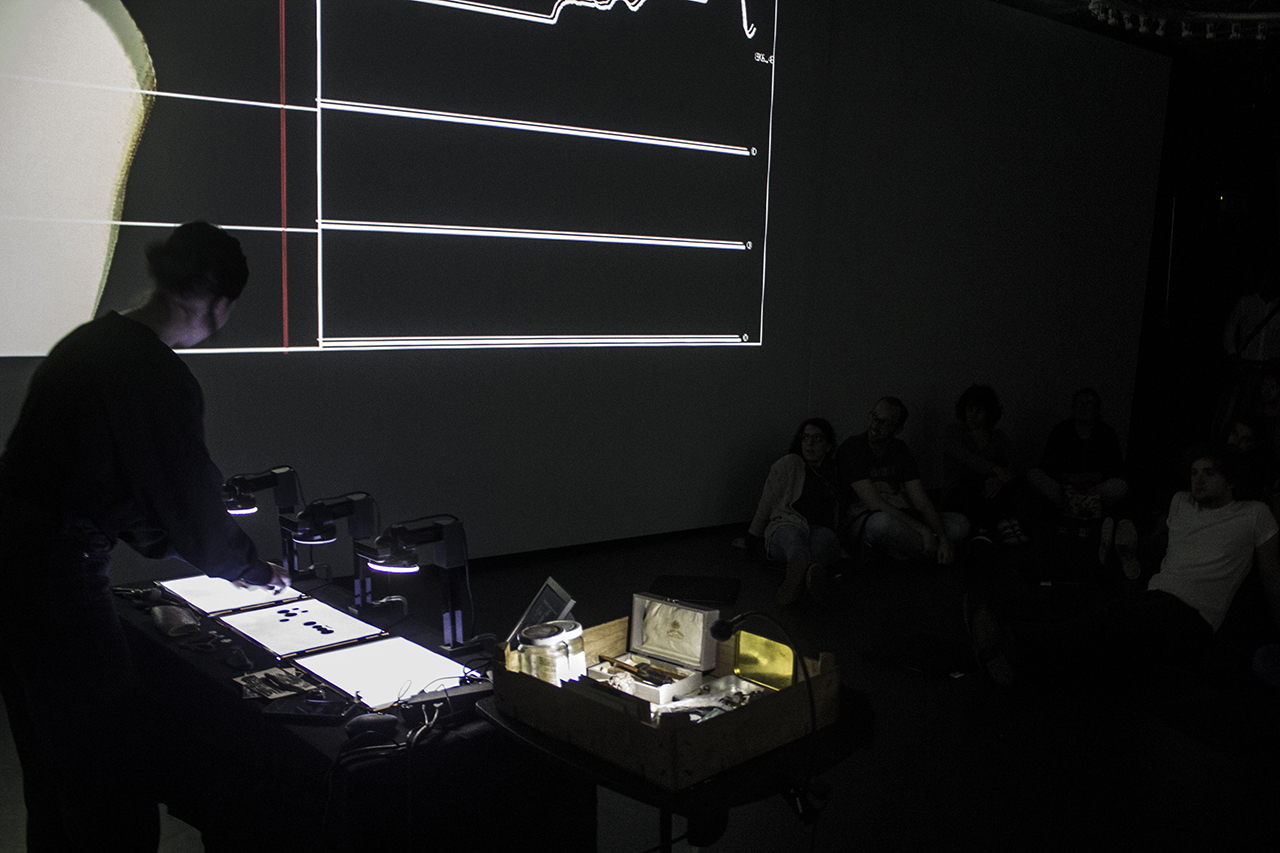

A performance and installation investigating lost memories and forms for live audiovisual composition.

produced by: Annie Tådne

Introduction

A hands-on interplay between material and computational properties, where instrumentation of physical objects is forming audiovisual resonances. Material structures are being decoded into fleeting sounds and through manual calibration a consensus, or maybe a conflict, elevate frictions of distant and present memories.

Concept and background research

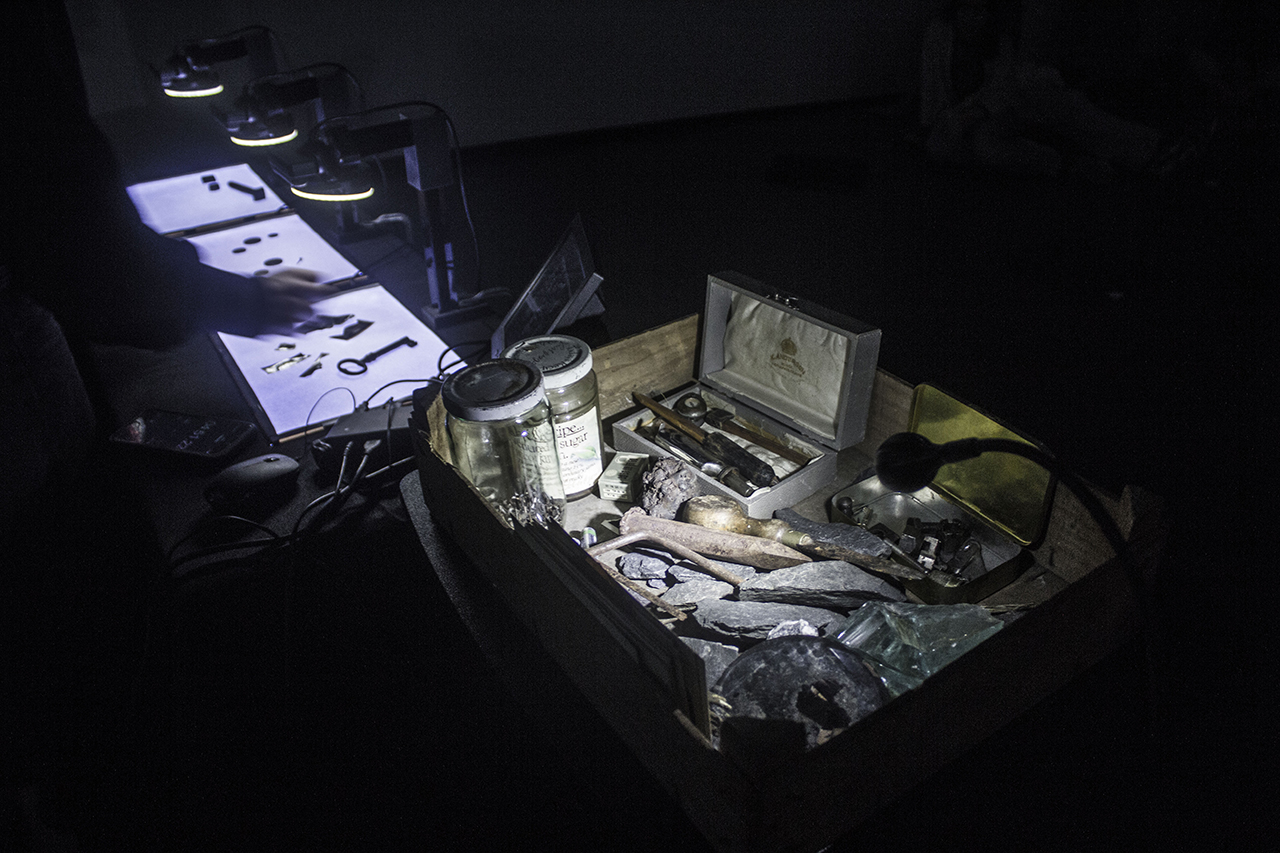

Boberg 1. is a performance/installation piece exploring frictions between now and then, between distant and present memories. By merging elements considered to be ‘real’, ‘analogue’, ‘physical’ and ‘synthesized’, ‘virtual’, ‘digital’, this piece creates audiovisual dissonances, where structures and materials might create an improvised fragmented story of a specific place. The collected items and sounds origin from a personal archive, an old archive spanning over centuries. As I was going through this archive, I was also unfolding traces of people with stories. By sorting out objects that once belonged to, and were used by, distant relatives of mine, I was reminded of these untold stories, stories no one ever can tell me. This is my way of giving life to these objects and giving life to new stories, new memories.

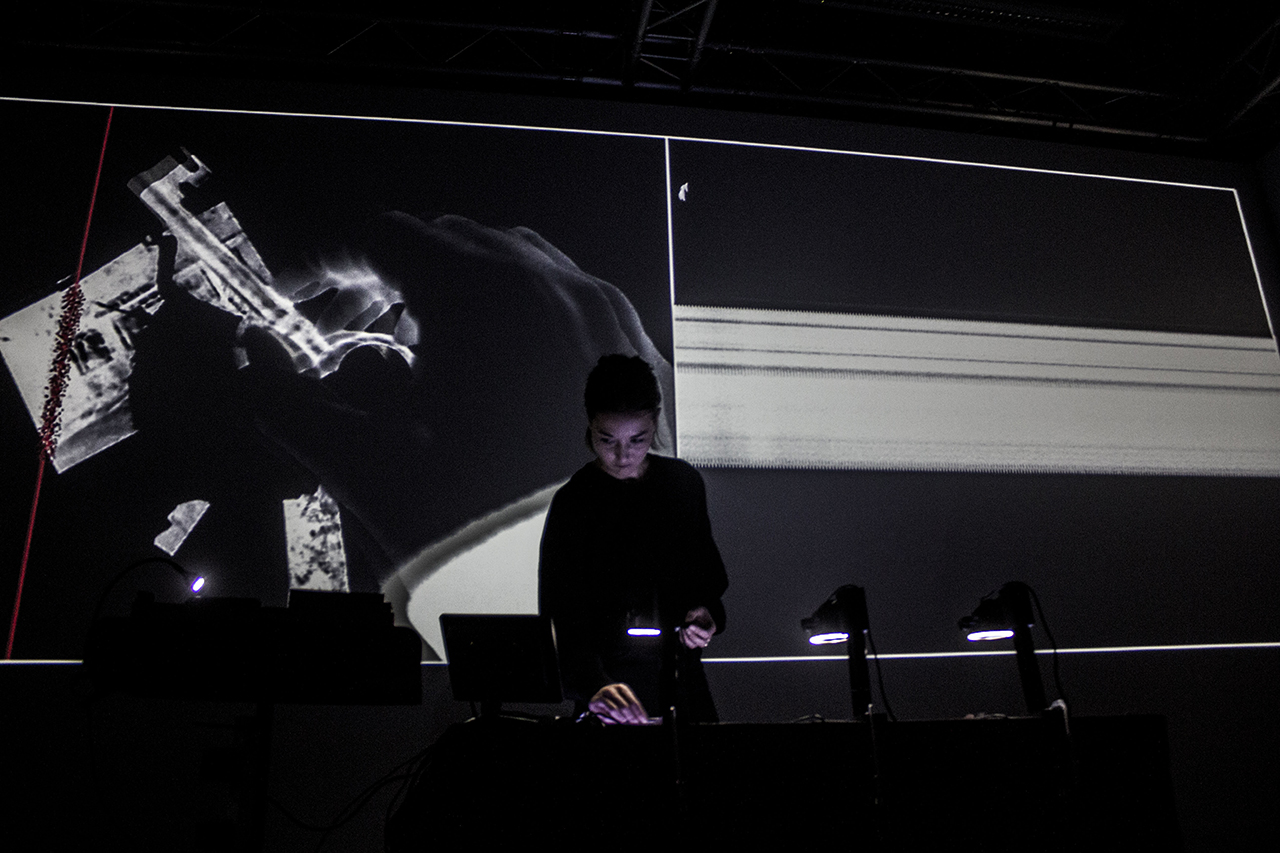

Through the built system, image and sound are experienced as one entity. The process is here transparent and direct, allowing the audience to perceive the building elements as they are changing over time through manual calibration, which allows the audience to create their own audiovisual story.

Three great artists influenced me while working on the piece. Daphne Oram for her extensive work with the Oramics Machine. She started developing the machine during the 50s, a machine that produced synthetic sounds with a graphical system, long before modern sequencers. The musician drew shapes on film to create a mask, which modulated the light received by photocells. I’ve been digging through the Orams archive, through her personal notebooks, correspondence, schematics and data sheets. You can see her life-long dedication as a true artist and inventor. She never sacrificed her integrity, choosing a difficult independent life for the sake of continuing her experiments with electronic music, despite all the institutional resistance she had to encounter.

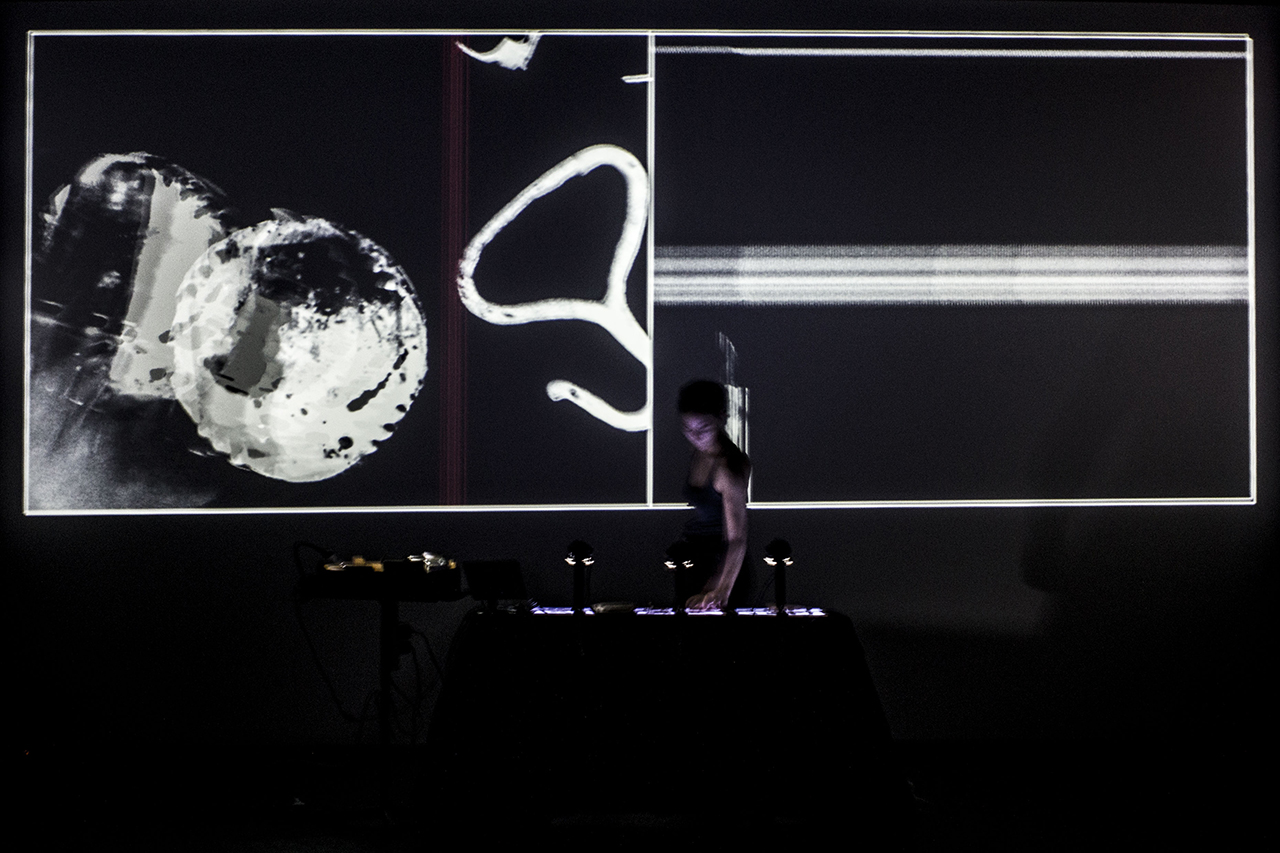

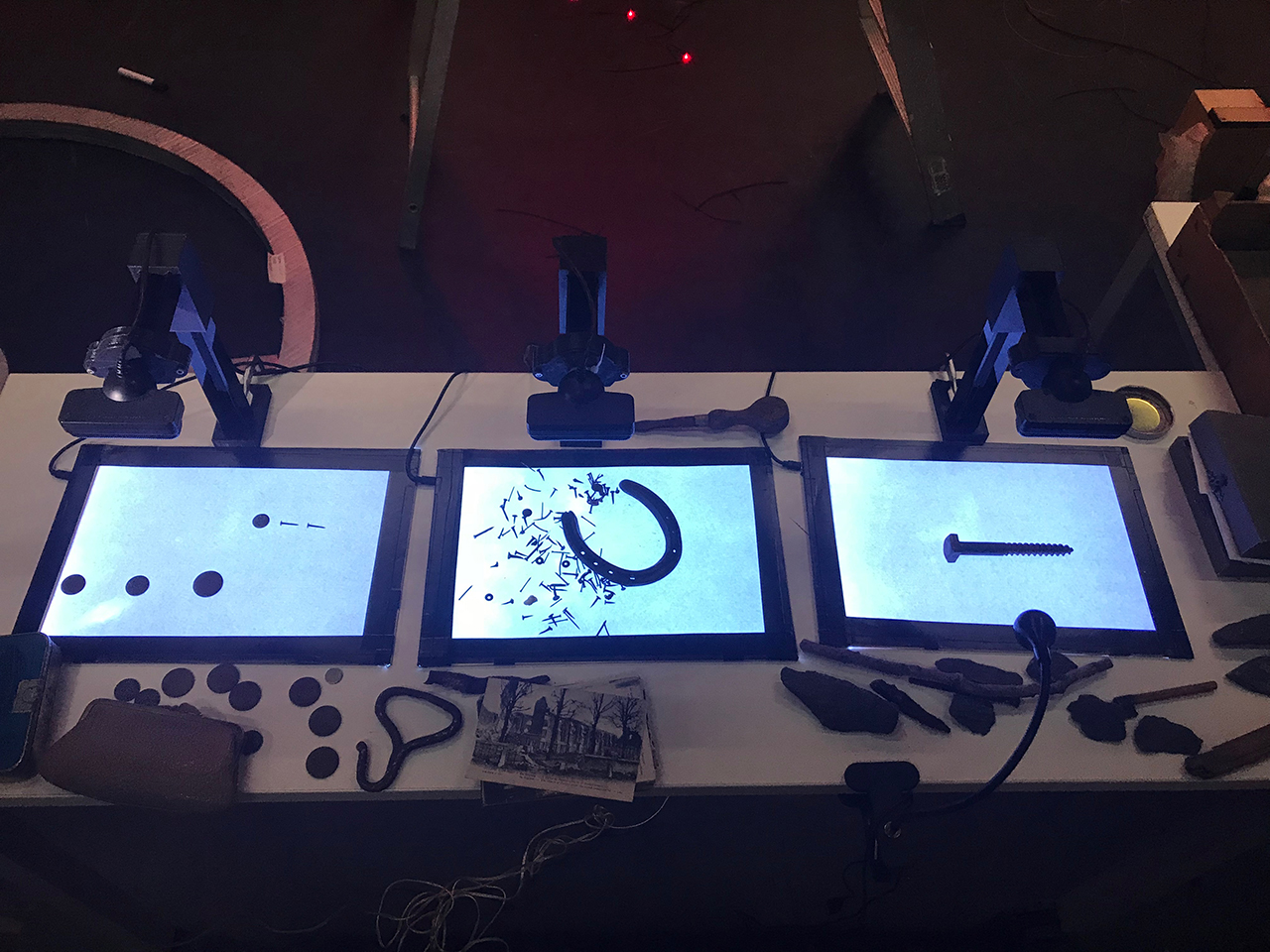

Man Ray has influenced me aesthetically with the “rayographs” he made. By placing objects on sheets of photosensitised paper, and exposing it to light, he created films and photos without the aid of a camera. The images are floating between abstract and representational, where the objects’ form and structure are central rather than its tactility or function. With his methods of experimental photography, he changed how photography was considered in the art world by its time and paved the way for following Surrealist writers and painters.

More recent artists that inspired me is the Berlin-based collective Transforma and their works with audiovisual performances, projections, installations, theatre and dance. They developed their own visual language by creating images and atmospheres through hands-on physical work. By use of cameras onstage, they focus on material properties of their subjects, establishing forms for abstract storytelling.

Technical

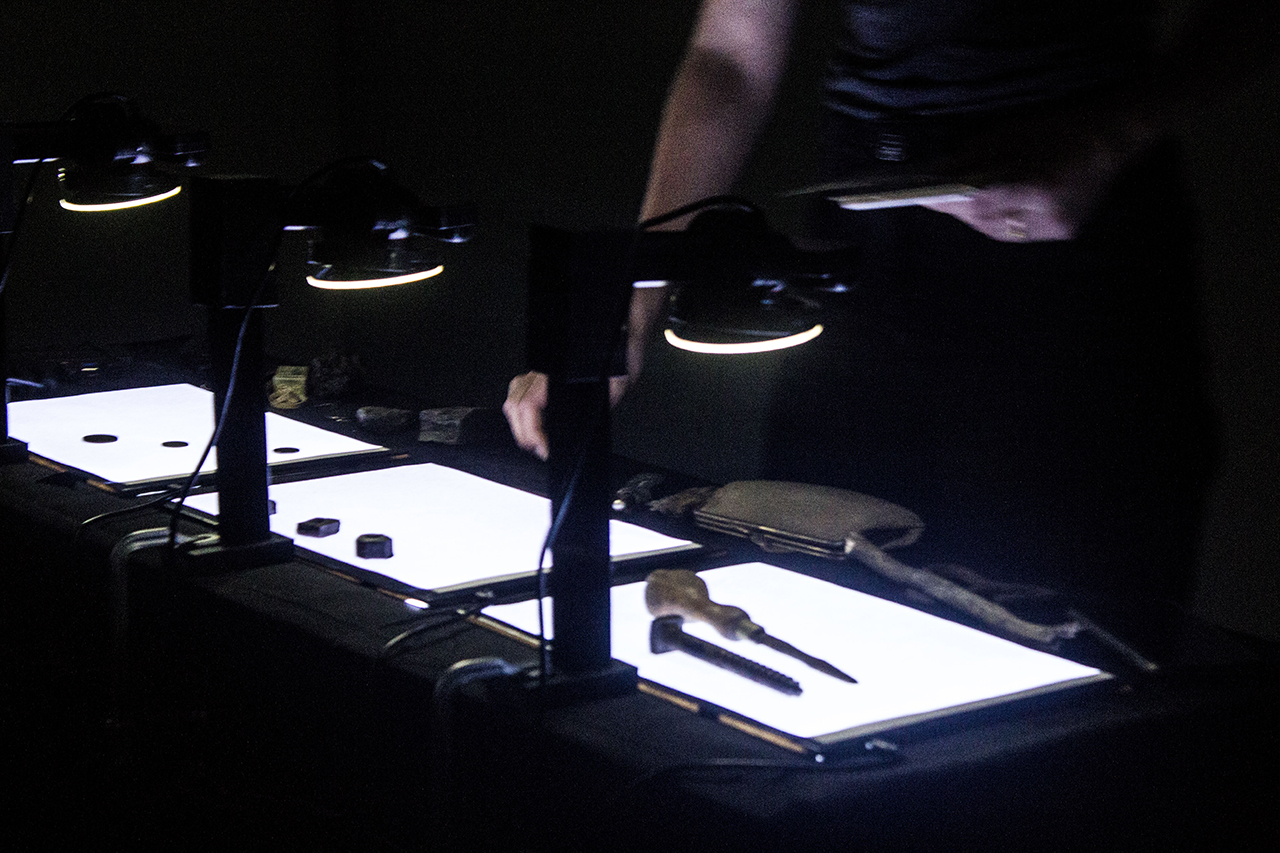

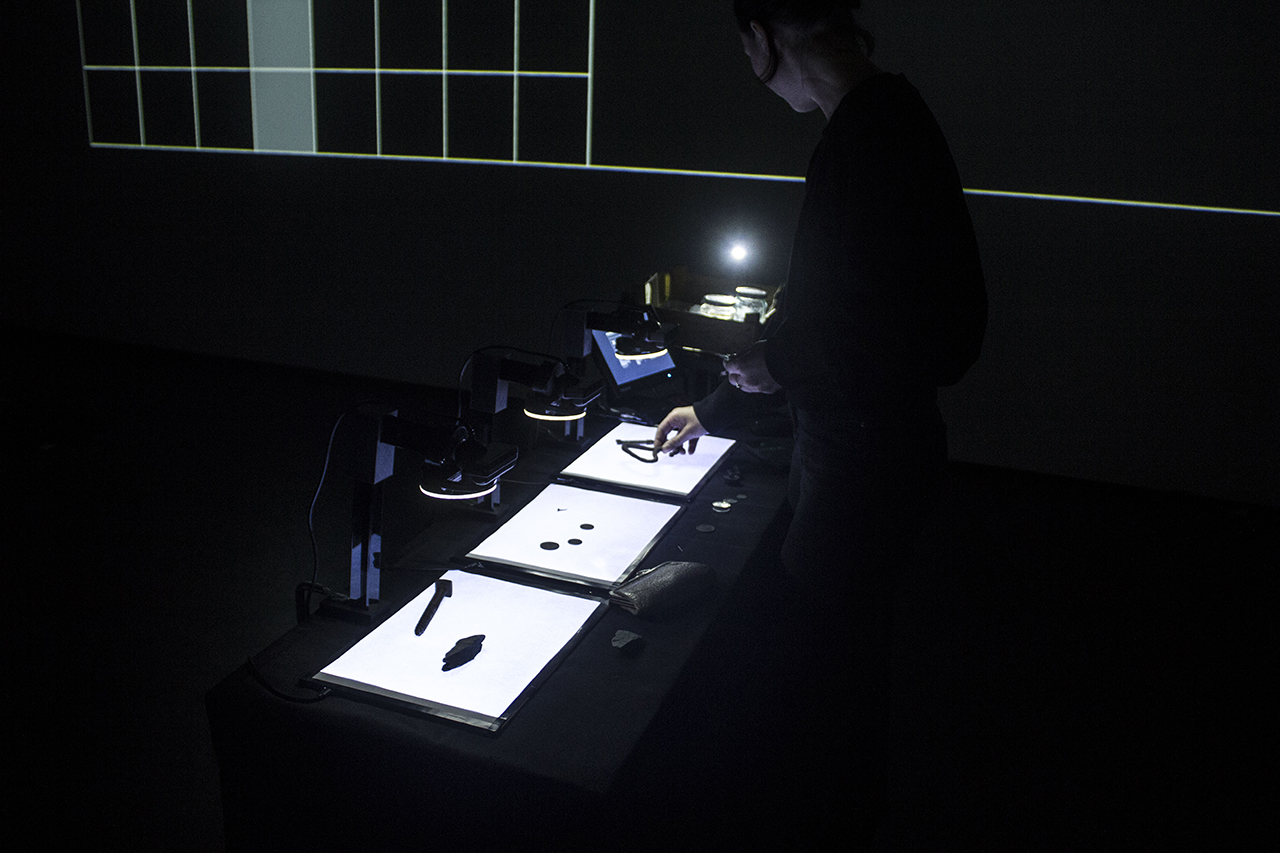

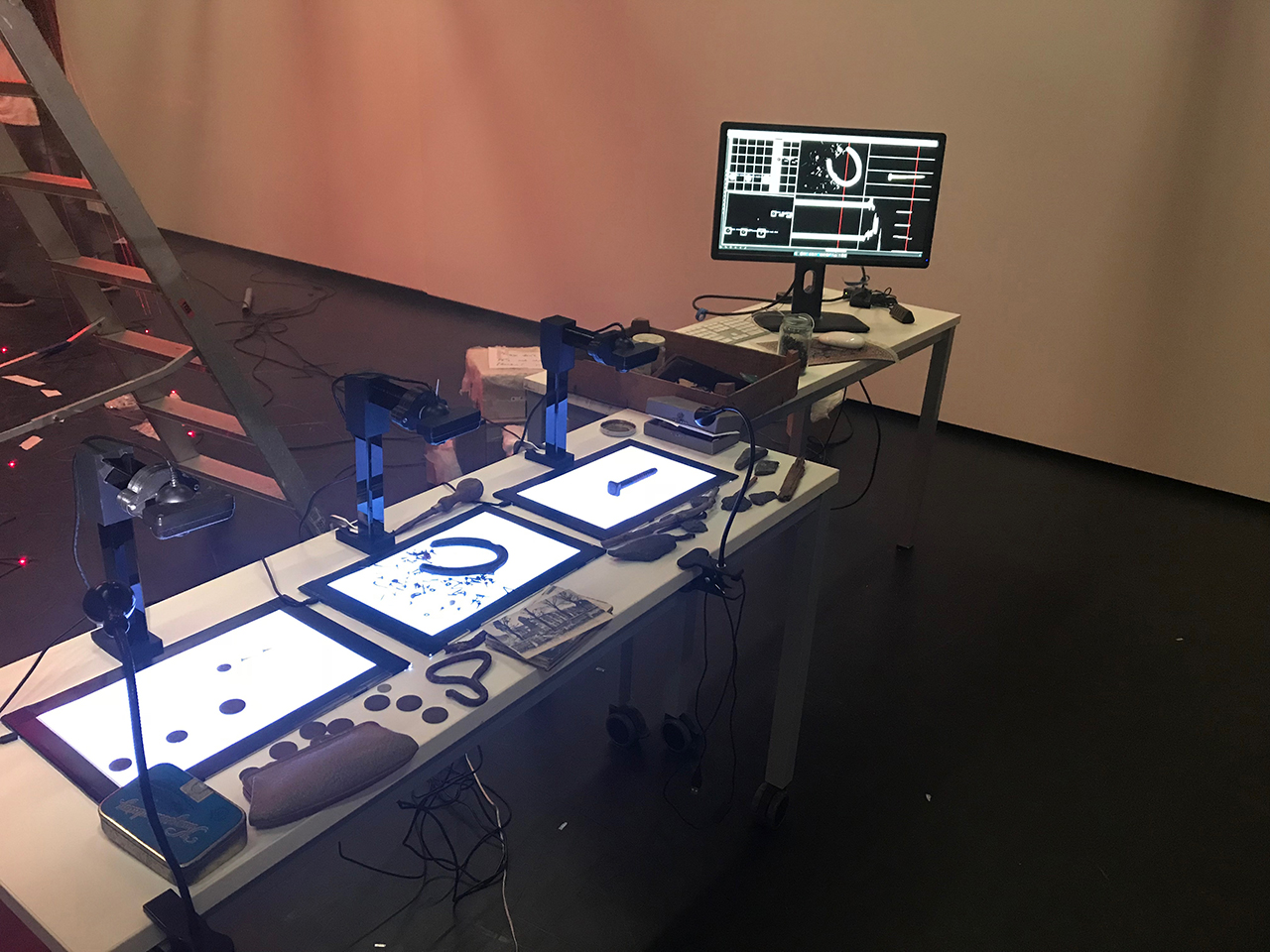

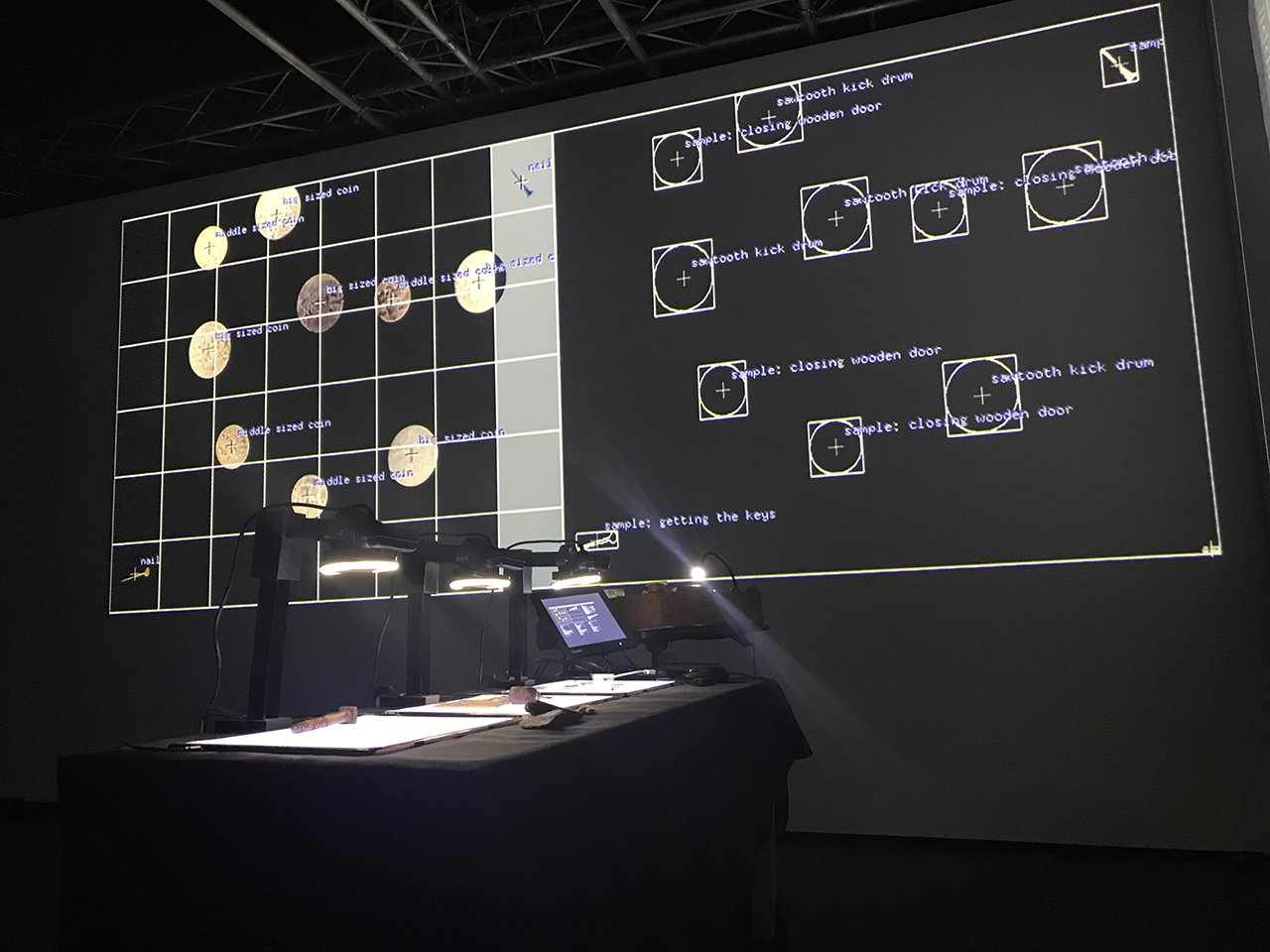

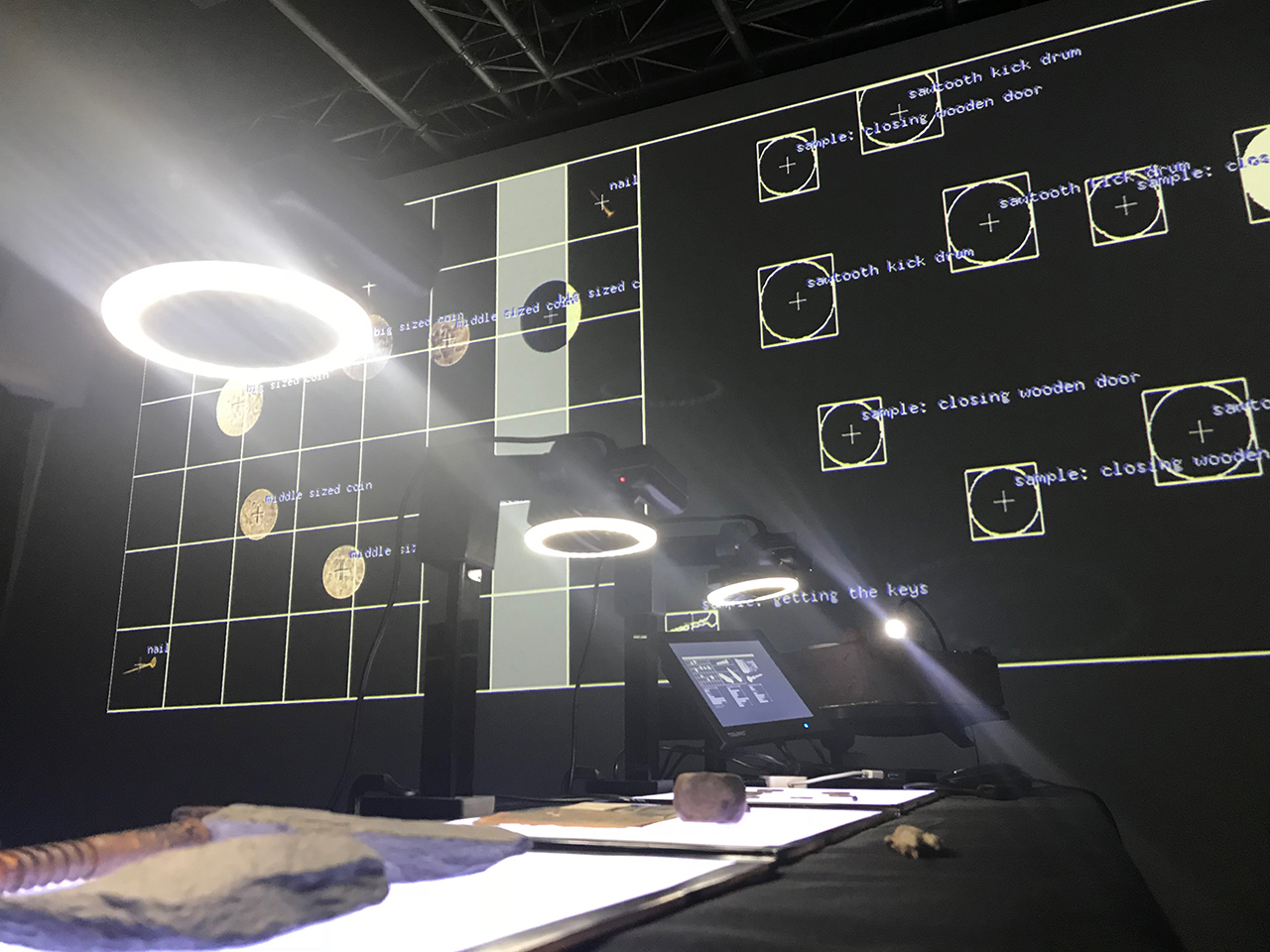

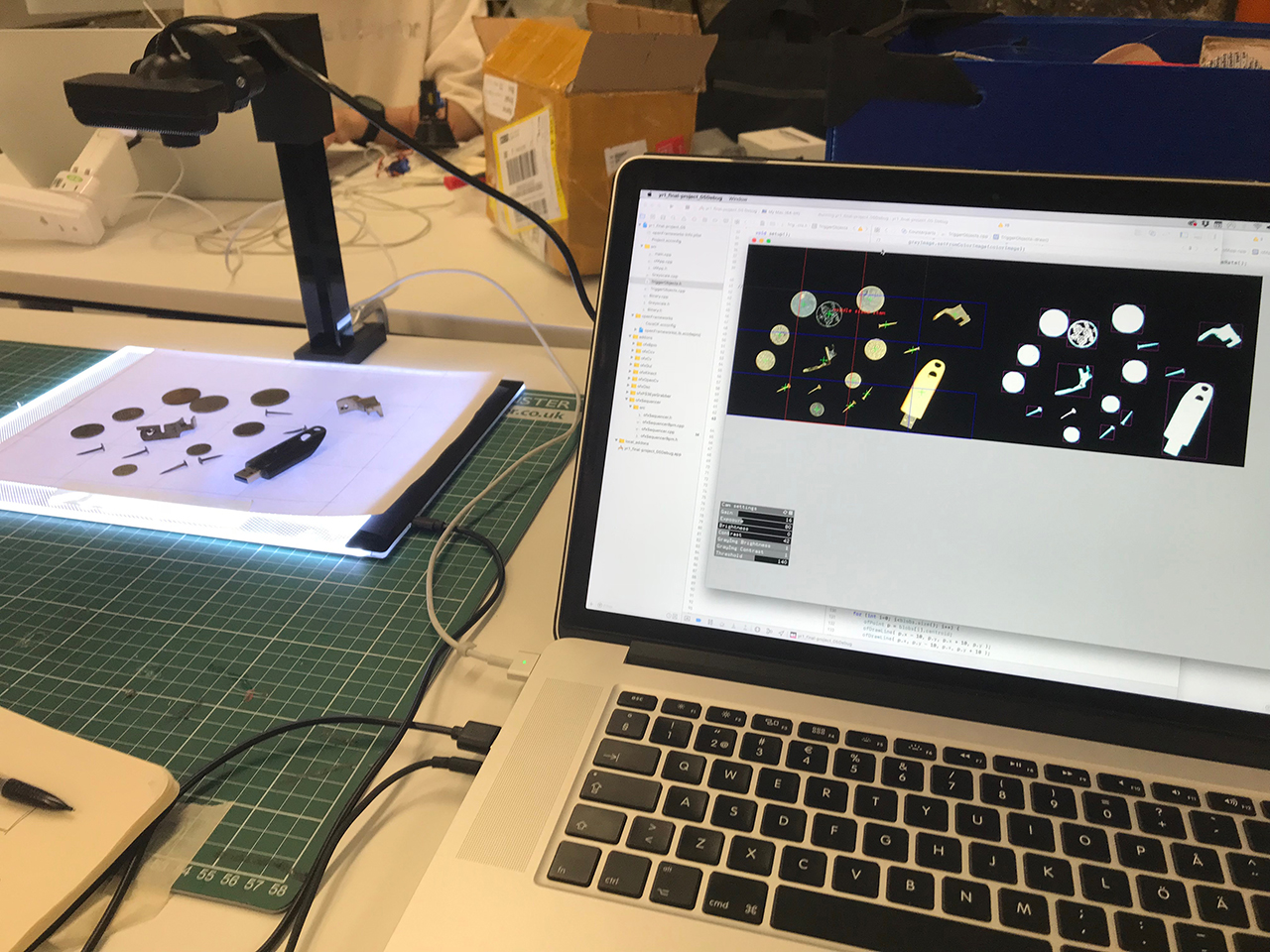

I wanted the technology to reflect the concept of frictions between now and then. The set design followed these principals, with strict graphical geometry, slick plastic lights and camera mounts are meeting the cluttered, old and rusty objects, distorted by time passed.

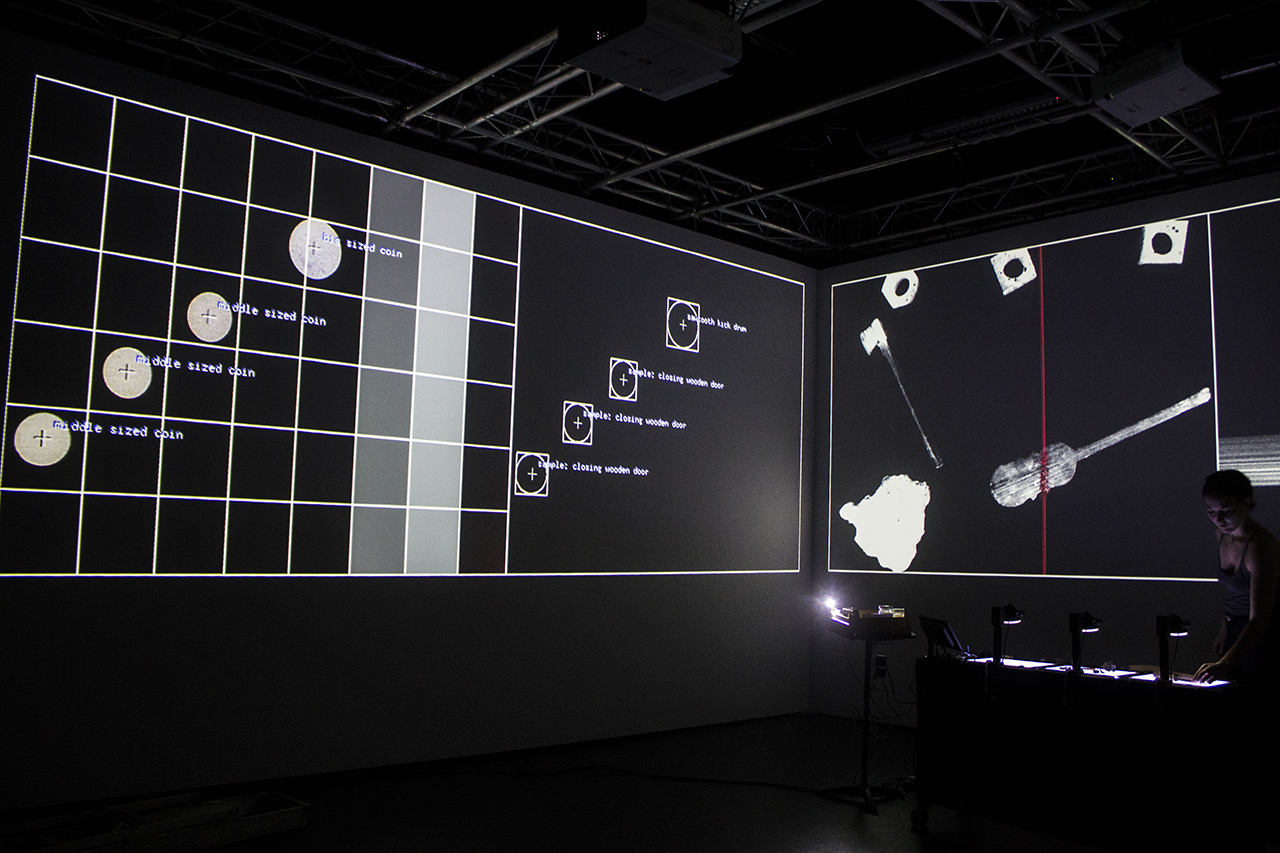

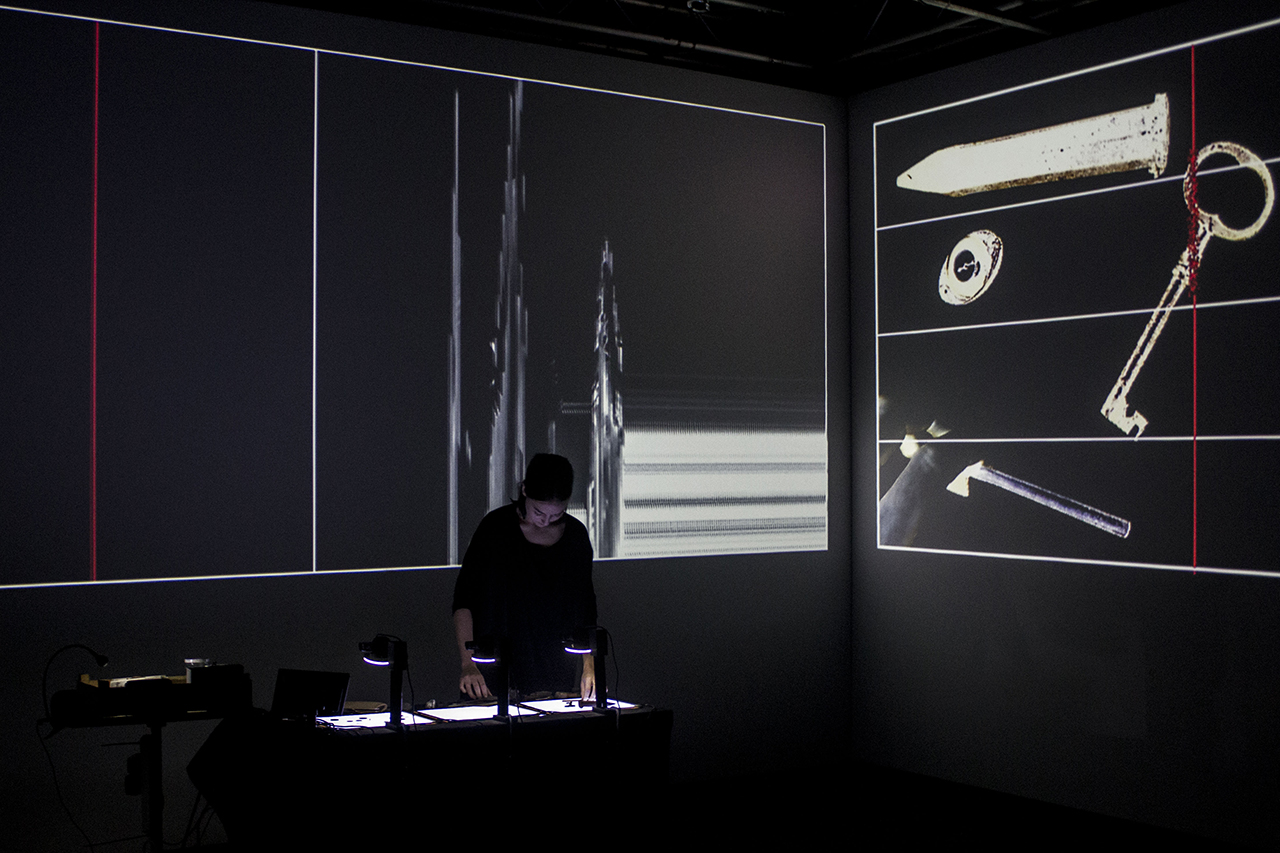

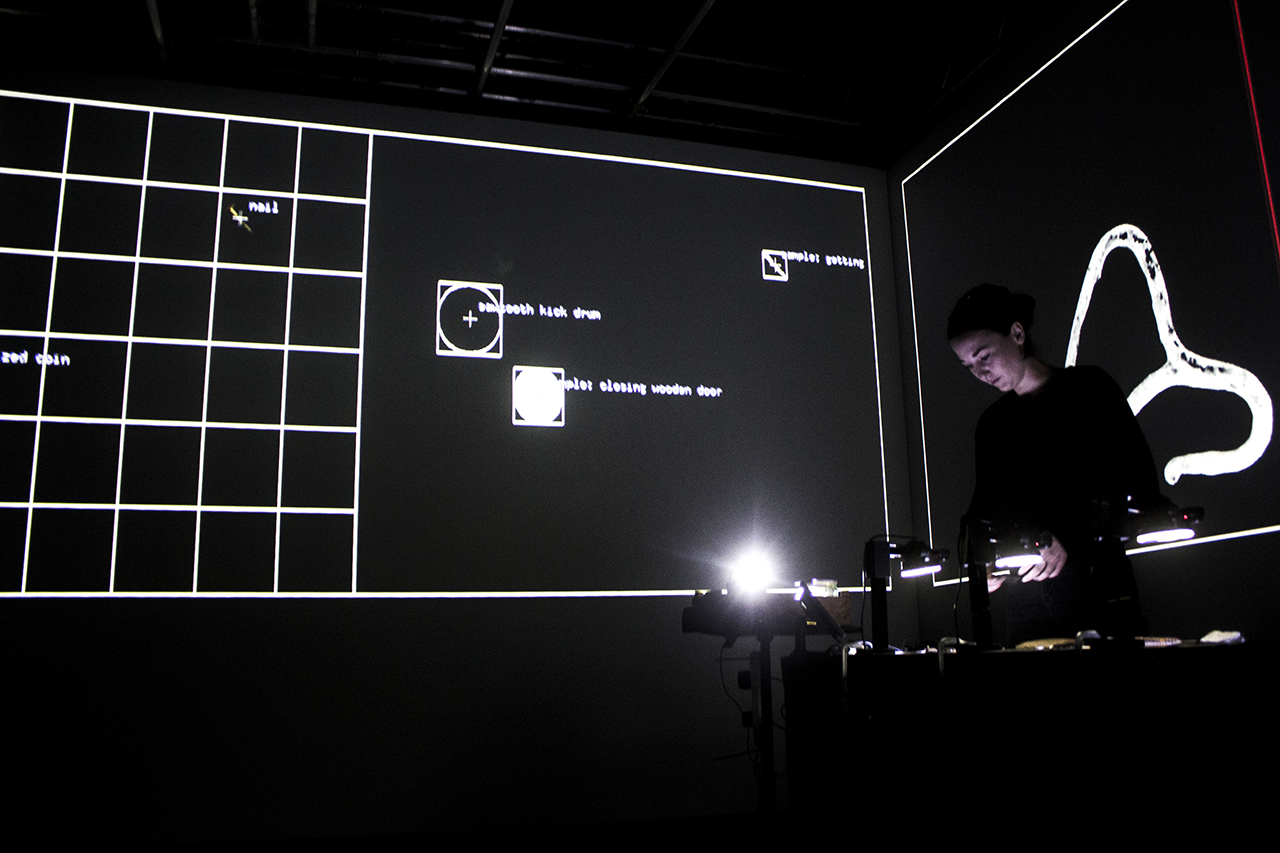

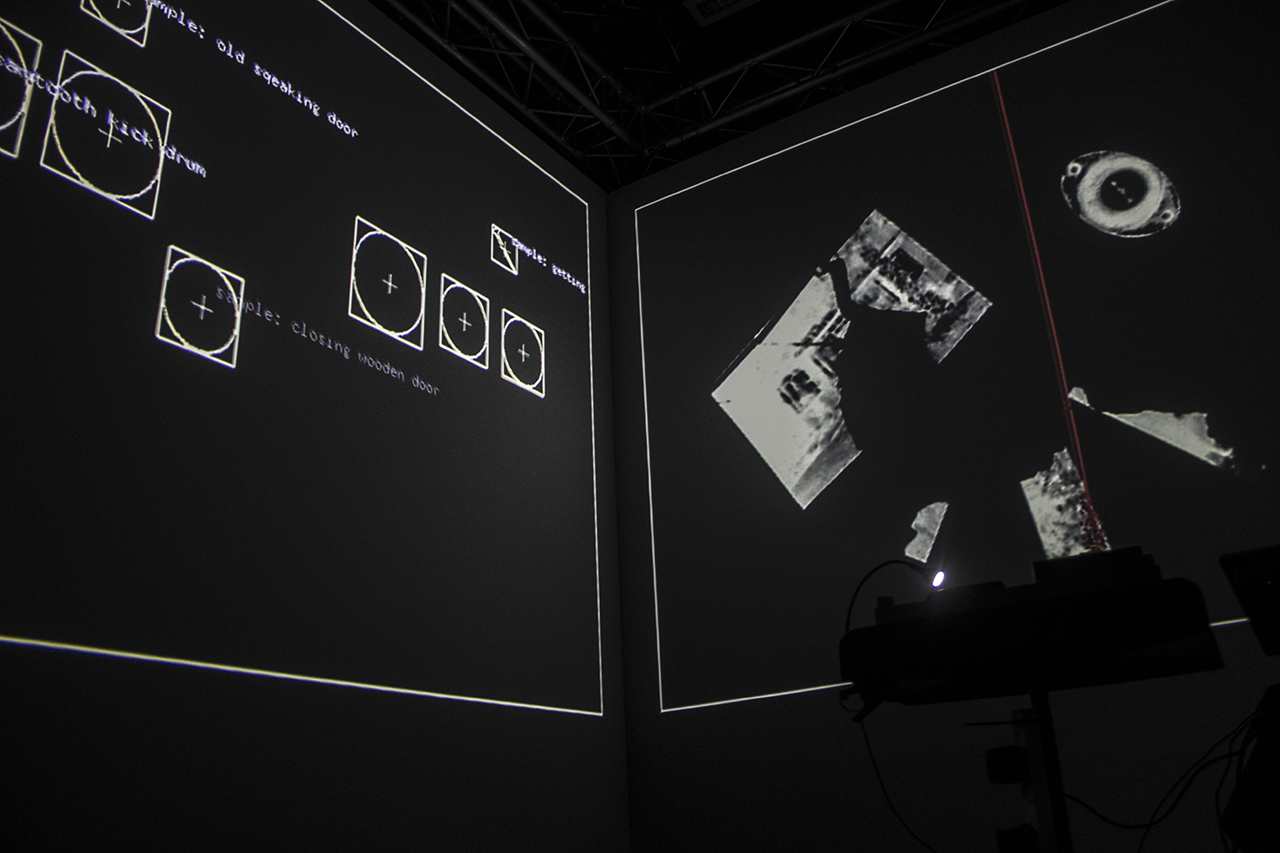

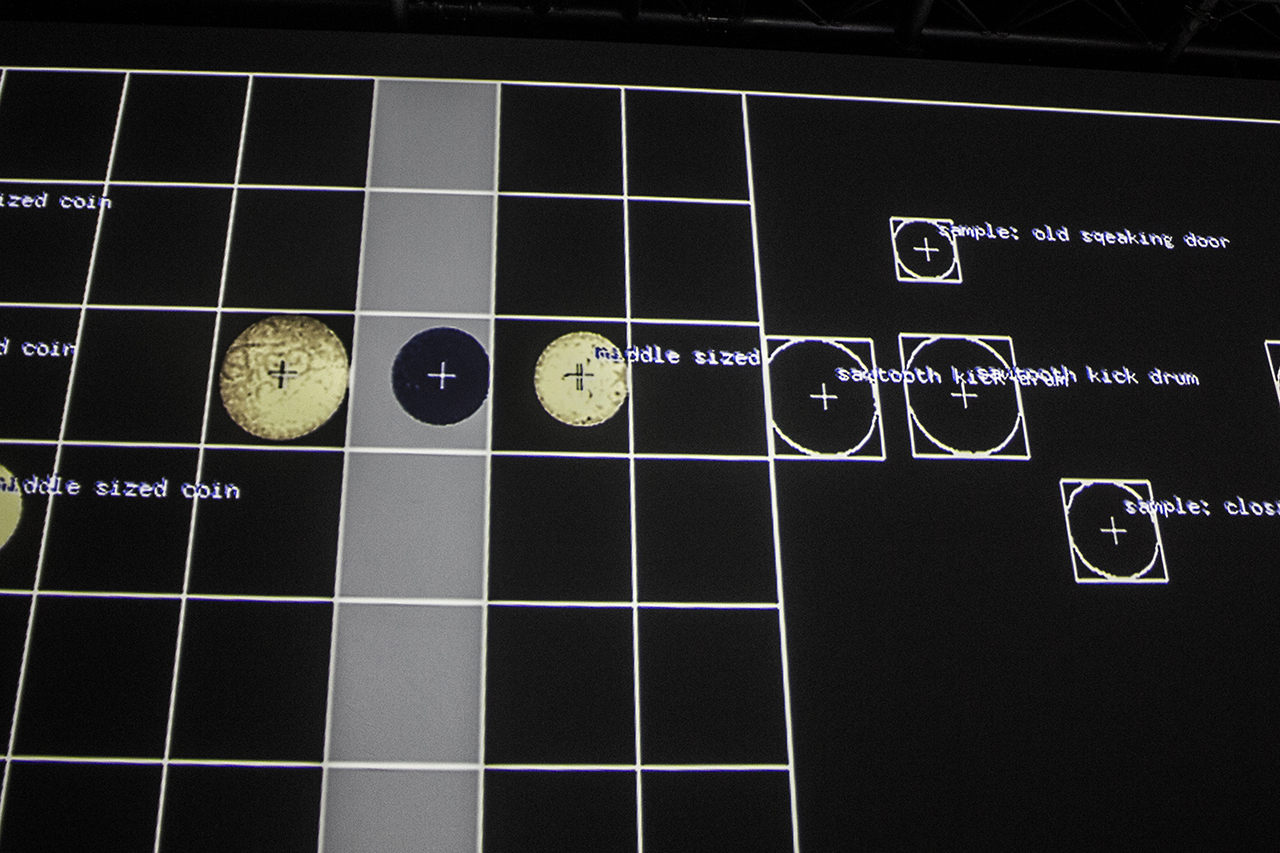

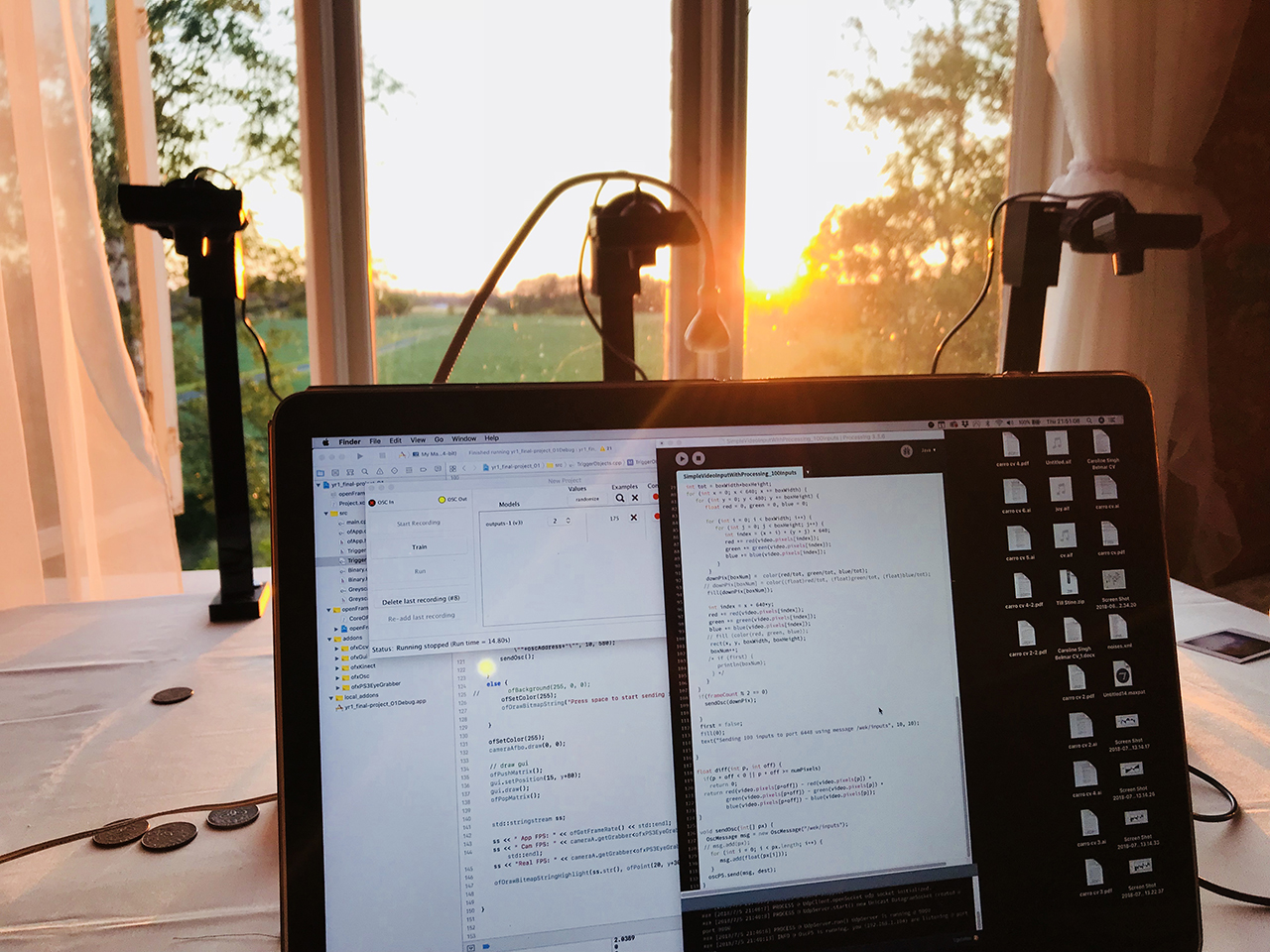

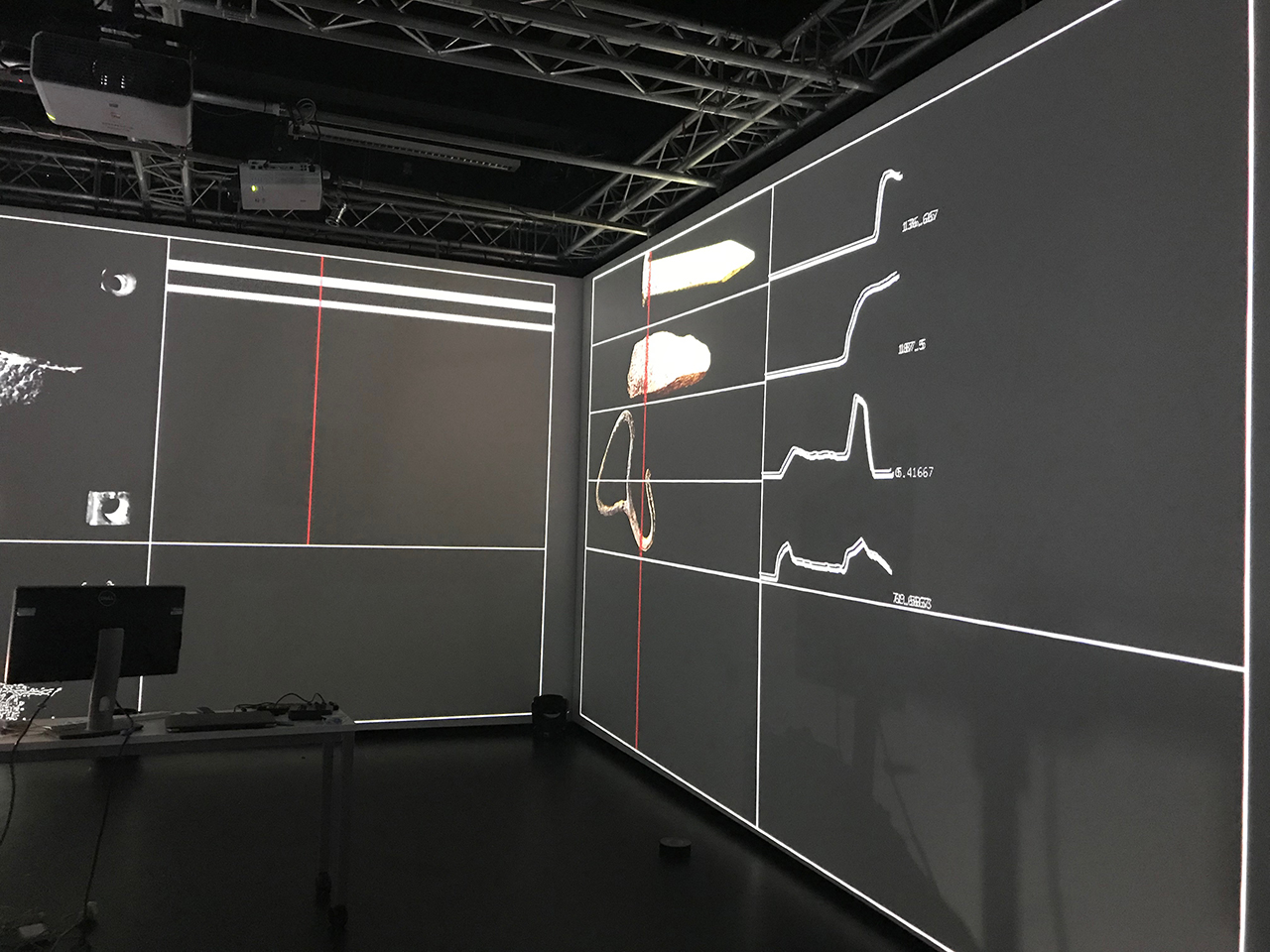

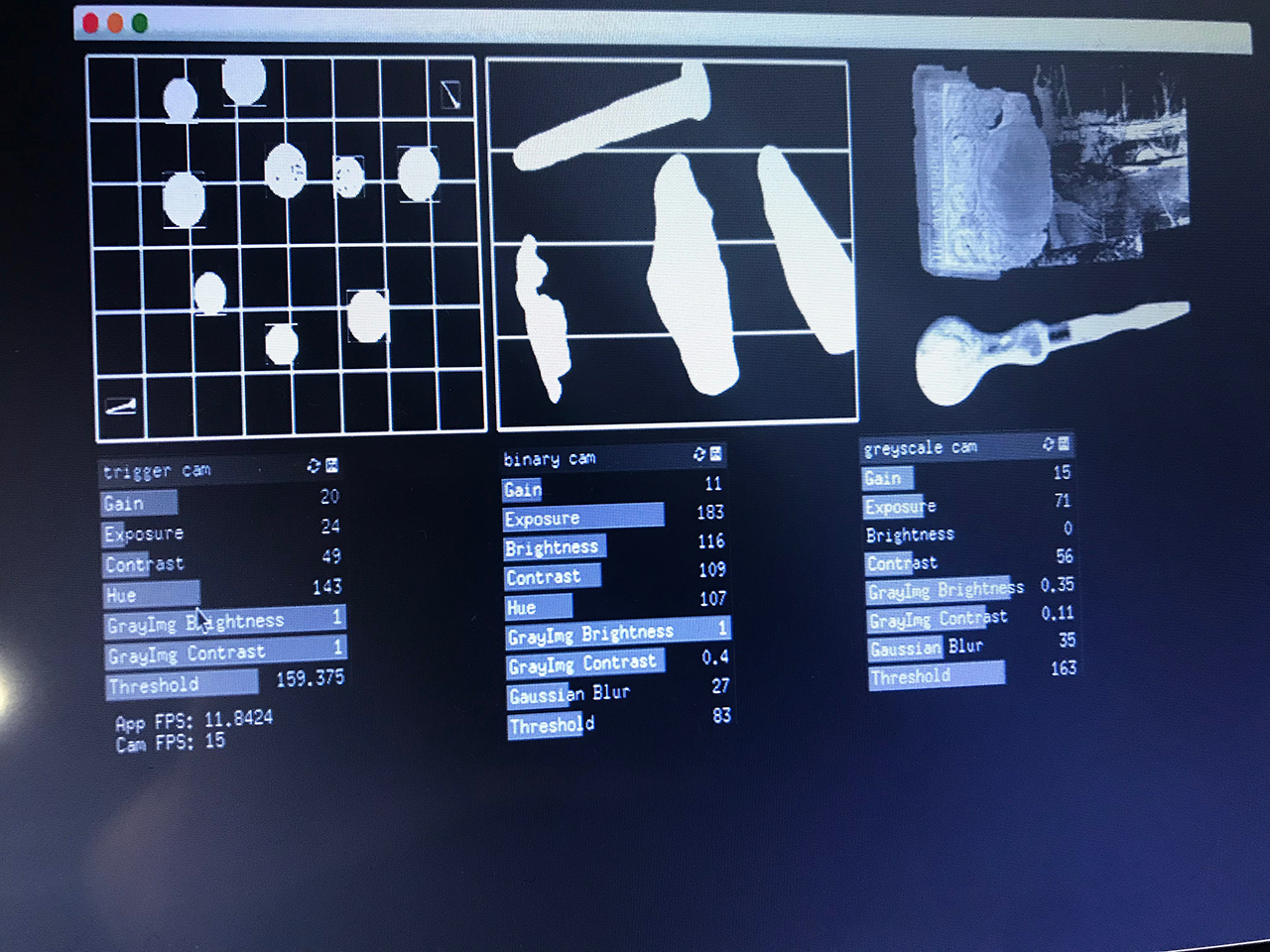

As I wanted the process to be responsive, direct and transparent, the translation of image to sound had to be straightforward and immediate. By use of the power of computer vision methods, I was able to create a real-time instrument out of three cameras. The cameras acting as my violin, and the objects acting as my bow. The visual output consists of a grid, where each screen is divided into input and output, where the output is a representation of how the sounds are controlled by the image or objects.

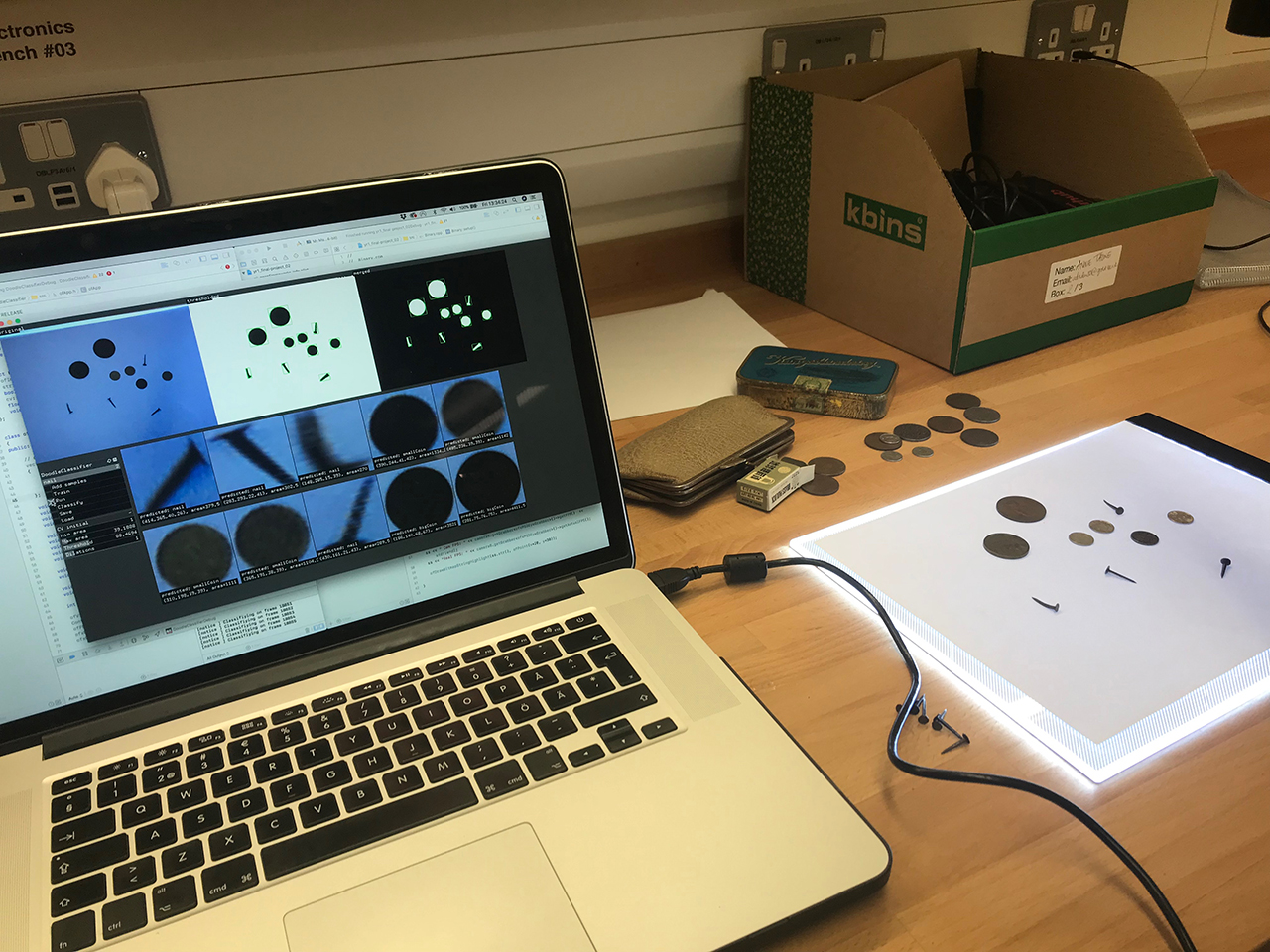

For establishing a coherent musical piece, each camera was programmed with different musical characteristics. First camera controls percussive triggering sounds, where the size of certain objects is triggering a specific sound. This camera module is a kind of analogy of a drum machine, where a coin or nail of different size could represent a midi note that is mapped to a short staccato sound. This is accomplished by blob tracking and calculation of each blob’s area.

Second camera module calculates the average grayscale pixel value of a scanning line. Depending on where the object is placed on the canvas, different frequencies of a sawtooth oscillator is triggered. The output area draws a version of what the scanning line “sees”, unfolding the pixels from the camera with a slit-scanning method.

The third camera is divided into four different sounds, and where the object is placed on the canvas determines what sound to be controlled. This is done by calculating the number of black pixels of the scanning line travelling over the canvas. The visual representation of the output is a graph, displaying the number of black pixels, which also is the same numbers controlling the sound.

The music is composed in MaxMsp, where I used samples of field recordings collected from the same place as the objects. This is combined with synthesised sounds, filters and reverb. The pixel values from the cameras are in real time sent from openFrameworks through OSC to MaxMsp, creating a direct response between image and sound.

The biggest technical challenge was computational performance speed and creating a real-time system without latency between image and sound. Due to the underlying idea of the project, I did not put value into image quality and high resolution, I was rather requiring a grainy and gritty image, making me able to go down in resolution for performance purposes. Although I was not able to obtain a higher framerate, something that could have made the expression more smooth and stable.

I also found it challenging to create a variation in the composition, making the performance interesting throughout. Due to the fact that the objects, position of the objects and its correlating sounds are hard coded and predefined, there is a limitation to what you can do musically. To find a balance between the number of objects on the canvas, and harmony in the sound was sometimes difficult and something to consider for future developments.

Installation

Accompanying the performance is an installation where the audience can interact with the system themselves. This is a way of making the system available in a broader sense and allowing people to create their own composition after seeing the performance.

Future development

For the future, I want to look into FFT and how I can create a more interesting visual representation of the sounds and the textural variations. I believe this would add audiovisual complexity to the piece and help me find a balance between the audial and visual composition.

I also want to look into how I can make the piece more musically rich, and into methods for how I can furthermore alter the different sounds, whilst keeping the transparency and responsiveness of the sounds.

Instead of calculating the size of blobs, it would be interesting to implement object recognition through data sets. This would open up doors for a large variation in objects and sounds but would also require a deeper level of computational processing implementations such as threading.

Self evaluation

My goal was for the audience to create their own story, and I am impressed by how a lot of people interpreted the piece differently. Comments from the audience ranged from thoughts about geology to archaeology to “Nordic noir”, and the sounds were described as industrial and monumental. I also appreciated the questions I got about whether I considered the piece to be a musical composition, sound art or soundscape, as I intended to break rules for musical composition and be floating between genres.

Even if I want to break rules, I also want to find a composition that is interesting throughout, with variations and dynamics in composition. I believe this is going to be my main focus for future developments. The piece works as a 10 min performance, but if I were to extend it in time I have to find new ways for modulation of the sounds and find a balance between the density in visual and audial elements.

References

ofxOpenCV

ofxCV

ofxPS3EyeGrabber

ofxOSC

yafr2~ Reverb by Randy Jones

MadMapper

Daphne Oram Collection. Archive of Papers, Personal Research, Correspondence, Photographs, and Recordings 1930–2003. London: Goldsmith’s College.

Demers, Joanna Teresa. (2010). Listening through the Noise: The Aesthetics of Experimental Electronic Music. Oxford University Press.

Goddard, M., Halligan, B., & Spelman, N. (2013). Resonances : Noise and contemporary music. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Hermann, Thomas, Bovermann, Till, Riedenklau, Eckard, and Ritter, Helge. “Tangible Computing for Interactive Sonification of Multivariate Data”. Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Interactive Sonification. Ed. Andy Hunt and Thomas Hermann. York, U.K.: Interactive Sonification community, 2007.

LaBelle, Brandon. Background Noise Perspectives on Sound Art. Second ed., 2015.

Laxton, S. (2009). Flou : Rayographs and the dada automatic. October, 127, 25-48.

Manning, Peter. “The Oramics Machine: From Vision to Reality.” Organised Sound, vol. 17, no. 2, 2012, pp. 137–147.

Rogers, Holly. Sounding the Gallery: Video and the Rise of Art-Music. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Transforma. (2018, September 10). About. Retrieved from Transforma: http://transforma.de/about/