Signs

Sign systems are products of human intelligence constantly changed by demand. As the science philosopher Jacob Bronowski remarked:

“The images play out for us events which are not present to our senses, and thereby guard the past and create the future - a future that does not yet exist, and may never come to exist in that form”.

We live in a time where general digitisation of channels wipes off the differences among individuals. The symbolic encompasses linguistic signs in their materiality and technicity. Letters and codes form a finite set without taking into account philosophical dreams of infinity. The imaginary, however, comes about as the mirror image of a body that appears to be. (Kittler,1999)

Signs is a human-machine collaboration on modern calligraphy and the explorational practice of new imaginary procedurally generated linguistic symbols.

produced by: Gabriel Comym

Background

The general digitization of channels and information wipes off the differences among individual media. Sound and image, voice and text are reduced to surface effects, known to consumers as interface.

Inside the computers themselves everything becomes a number: quantity without image, sound, or voice. The monopoly of data and bytes we live today, once began with the monopoly of writing. Writing functioned as a universal medium and whatever else was going on dropped through the filter of letters or ideograms.

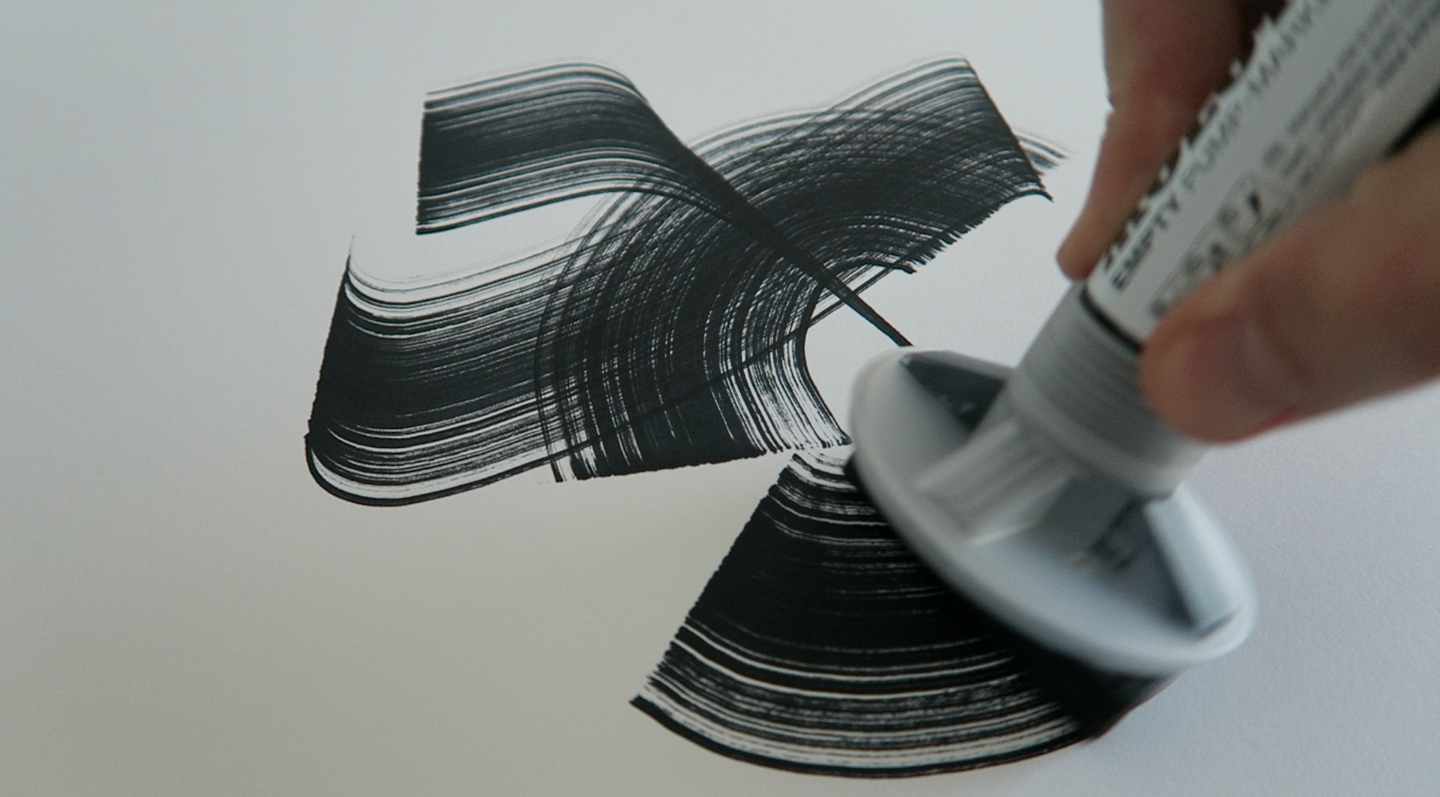

Once a hand took hold of a pen, something miraculous occurred: the body, which did not cease not to write itself, left strangely unavoidable traces. Signs is an experiment on modern calligraphy compositions created by the use of computational methods, but also a celebration of the beautiful human and material imperfections.

Our handwriting is the mirror of all our interior nakedness. The procedural nature of the construction of historical scripts is the core insight linking to how programming language is interpreted by the machine. Instruction after instruction, step by step, line by line. Intentional actions somewhere far from any given meaning are taken until everything is printed on screen, the user interface, or the canvas. Only then can we, the observers, project our individual interpretations on it.

"If one reads in the right way," Novalis - a poet, author, and philosopher of early German Romanticism - wrote, "the words will unfold in us a real, visible world." (Kittler,1999)

Once typing became an option, writing lost all its sensuality. In standardized texts, paper and body, writing and soul fall apart. A finite set of ready made characters do not store individuals; their letters do not communicate a beyond that perfectly alphabetized readers can subsequently hallucinate as meaning. (ibid.)

The process

The design process consisted of four distinct phases: Discovery, Definition, Development and Delivery.

Discovery:

I tried to understand my needs as a designer and thought about how to assess and combine these needs to the course deliverables. At this point, without the intention of answering it, one of the most important questions was raised, which was the idea of what makes a piece of artwork authentic. What is authenticity? Another personal need that was taken into consideration was the fact I have been working on screen projects for the last twelve years of my professional life. I felt it was the right opportunity for me to take my work out of the screen and get my hands dirty.

Definition:

After researching various manual processes such as painting and screen-printing, I finally decided to take calligraphy as my channel of expression/communication for this final course work. Calligraphy has been one of the few artistic activities I’ve had as a hobby along the years.

Development:

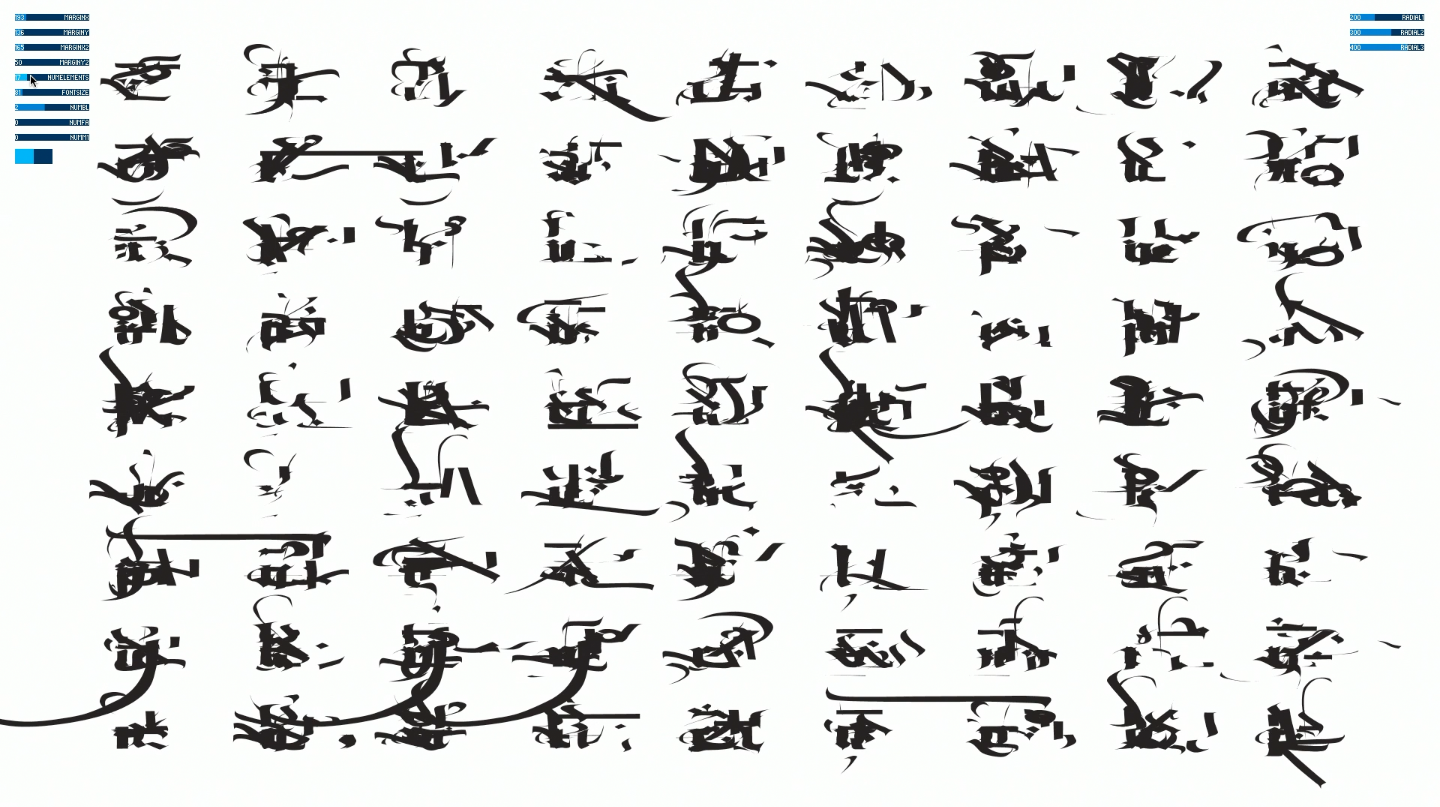

The idea of the human-machine collaboration was developed by creating a custom software running in process on top of Java. The whole process starts by manually breaking down a series of different calligraphy scripts from A to Z, stroke by stroke. For instance, a Gothic script generated a bank of 111 different strokes. The same breakdown process was carried out on other different scripts giving me a total of 889 different strokes.

The machine visual composition is created by calling the algorithm to read its own lines, identifying blocks of written code and breaking down all the found characters into a set number of strokes. For instance, the character “T” calls for a temporary variable of 2 strokes and the character “E” calls for a temporary variable of 4 strokes.

The selected temporary variable number calls back the calligraphy strokes directly from the assets folder and arranges the different scripts into one following an invisible grid. The grid can be controlled and customised by the use of GUI sliders on screen making the final composition look visually pleasing and adaptable to any canvas size.

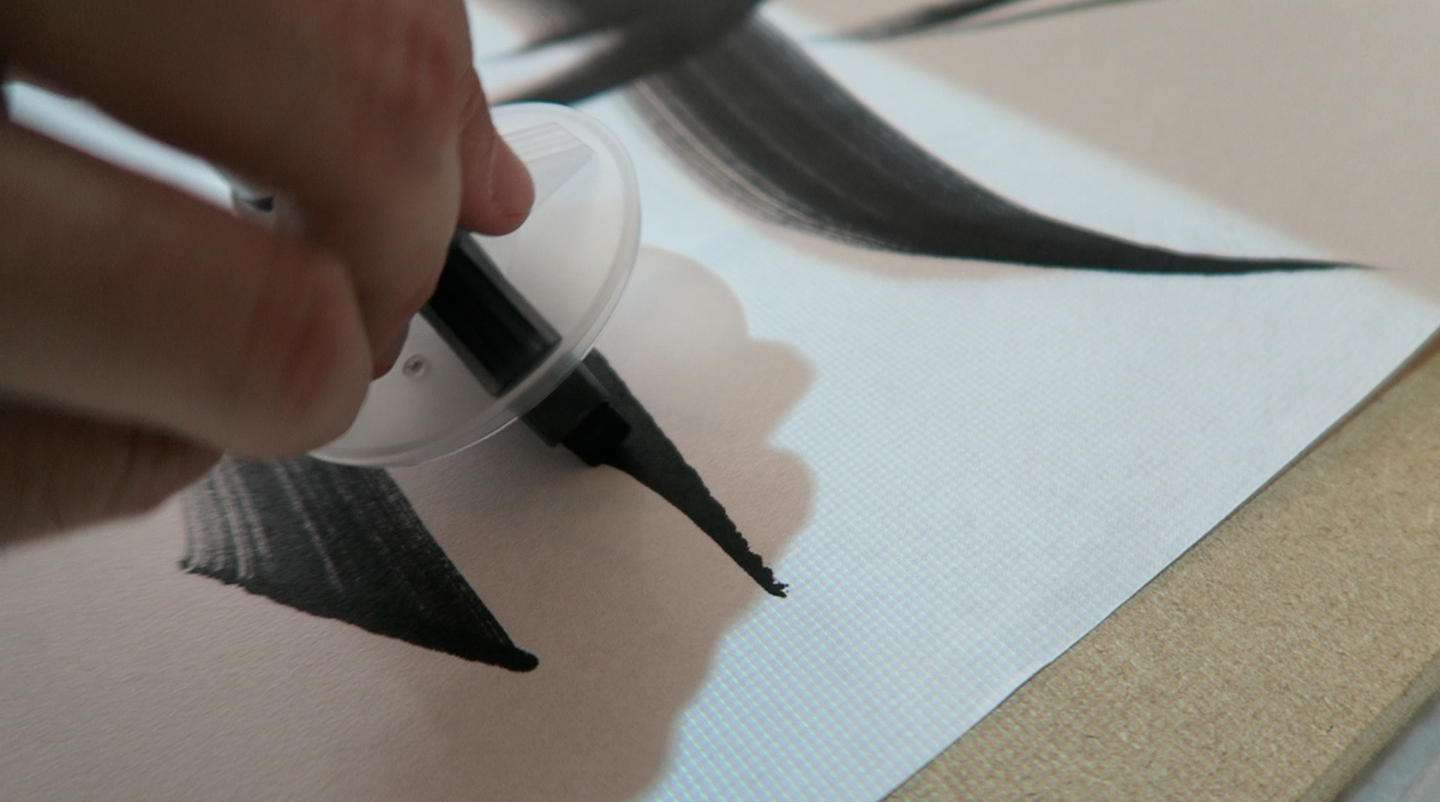

During this phase many different types of papers and fabrics of varying sizes and textures were tested against a range of inks, tools and markers.

Delivery:

My biggest challenge was to strip down all the irrelevant aspects of the artwork and to stay true to the core idea. The process of simplification is one of the most challenging parts of the design process. When everything was pure hot air and blur, it was time to remove all the noise.

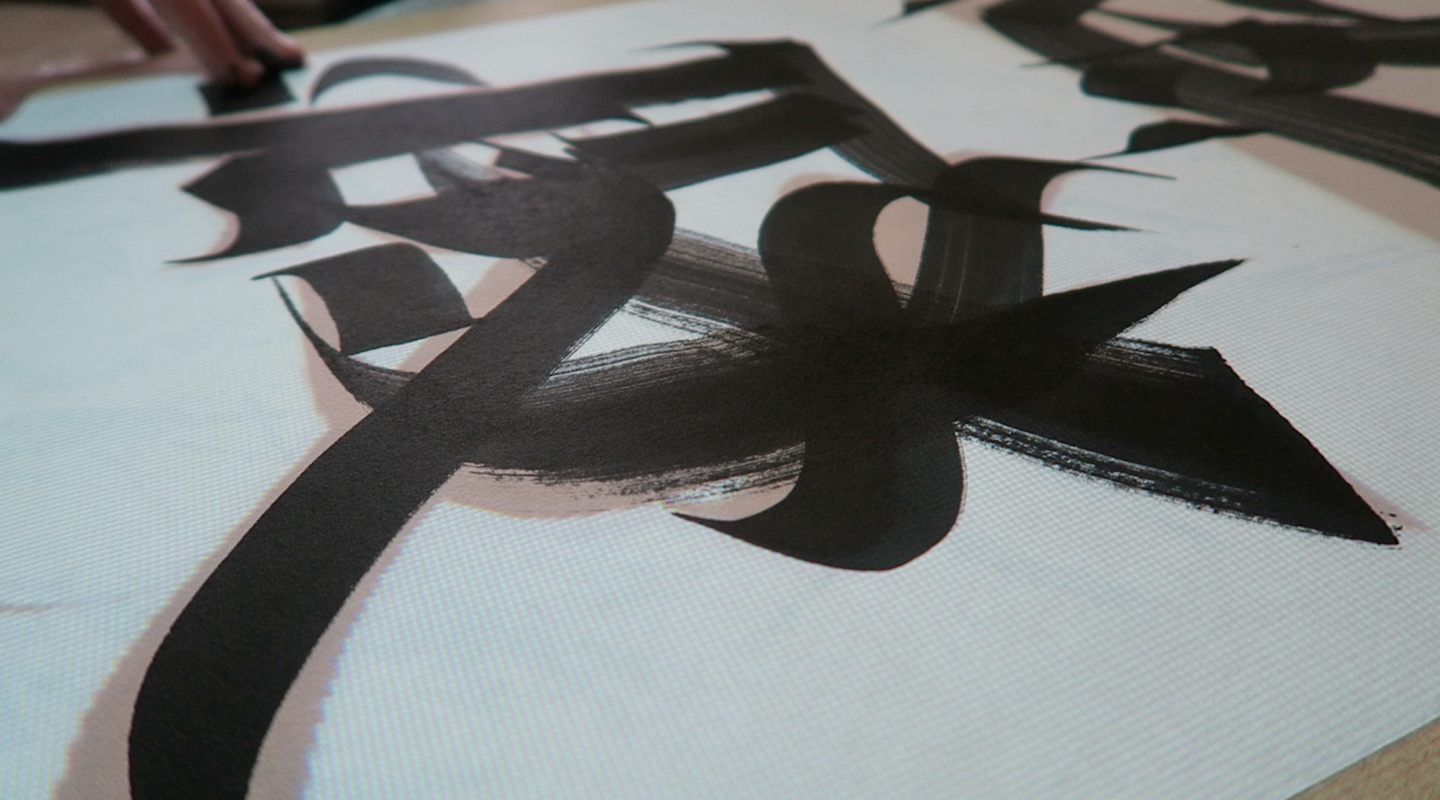

In the final delivery period all the work came together by taking the machine composition out of the screen and projecting it onto the 40 metre long Japanese fine calligraphy scrolls. The artwork that started by being created manually on paper, comes back to its original medium by being repainted and revealing what the machine can’t: analogue characteristics of the materials influenced by the tools, room temperature, paper texture, ink absorption and light in conjunction with natural human gestures and imperfections. My handwriting exposes me in a way no purist digital process could do.

A suggested semiotic observation:

Semiotics:

The human species is consumed by a need to unravel the reason for its existence on this planet. This has led it to create “signs” and “sign systems,” such as languages, myths, art forms, sciences, and the like, to help it do exactly that. The study of these and the laws that govern them in cultures throughout the world comes under the rubric of semiotics. The central task of semiotic analysis can be reduced, essentially, to determining the nature of the relation X = Y.

X = signifier (= the physical part)

Y = signified (= the conceptual part)

The brain’s capacity to produce and understand signs is called semiosis, while the knowledge-making activity this capacity allows all human beings to carry out is known as representation. Figuring out the meaning of X = Y is not, however, a simple task and it is limited by the observer’s cultural capacity, understanding and decoding its conceptual part. (Danesi, 2004)

Code:

When we read a block of text, we are only able to encode and decode messages if we know the language used. Language is a system that provides the structures and specifies the relations that these bear to each other for the purpose of making messages. The term used in semiotics to refer to all such systems is code. These can be defined as systems of signs (verbal, visual, gestural, etc.) that have specific properties and, thus, can be used over and over to encode and decode texts and their messages. Indeed, the words encode and decode reveal, by themselves, that the making and interpreting of messages involves use of a code. (Danesi, 2004)

The semiosphere - a concept originating in the work of the great Estonian semiotician Jurij Lotman - is the term used in semiotics to refer to culture as a system of signs. The semiosphere, like the biosphere, regulates human behavior and shapes evolution. But although they can do little about the biosphere, humans have the ability to reshape the semiosphere any time they want. This is why cultures are both restrictive and liberating. They are restrictive in that they impose upon individuals born into them an already-fixed system of signification. This system will largely determine how people come to understand the world around them - in terms of the language and other codes that they learn in social context. (Danesi, 2004)

This artwork plays exactly with the deconstruction of these formal structures of language and the already-fixed system of signification, extending this concept and inviting the observer to hallucinate new meanings and fill any gaps as they wish, typically by reinventing new signs, altering already-existing ones to meet new demands, borrowing signs from other cultures, and seeing what may never come to exist.

As the philosopher of science Jacob Bronowski remarked, this is the feature of the human mind that makes it unique among all species:

“The images play out for us events which are not present to our senses, and thereby guard the past and create the future - a future that does not yet exist, and may never come to exist in that form. By contrast, the lack of symbolic ideas, or their rudimentary poverty, cuts off an animal from the past and the future alike, and imprisons it in the present. Of all the distinctions between man and animal, the characteristic gift which makes us human is the power to work with symbolic images.” (ibid)

Bibliography:

Kittler, Friedrich A. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1999. Print.

Danesi, Marcel. Messages, Signs, and Meanings: A Basic Textbook in Semiotics and Communication. Toronto: Canadian Scholars', 2004. Print..

Source code:

You can find the the source code on Github.

References:

This code was written from scratch only with the help of Processing Official Documentation.